Chahta Anumpa: a Multimodal Corpus of the Choctaw Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborating for Prosperity with American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities

Collaborating for Prosperity With American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities USDA Rural Development Innovation Center Together, America Prospers From 2001 to 2018 USDA Rural Development invested more than $6.2 billion in Indian Country and Alaska. USDA Rural Development places a high value on its relationship with Tribes, American Indians, and Alaska Natives. We are committed to increasing investment throughout Indian Country and Alaska. We are collaborating and partnering with Tribes to realize a brighter future for families, children, and Tribal communities. Through loans, grants, and technical assistance, Rural Development makes critical investments in infrastructure, schools, health clinics, housing, and businesses, to benefit Native families and communities across rural America. Rural Development supports American Indians and Alaska Natives in holistic, sustainable, and culturally responsive ways. Every Tribal Nation has unique assets and faces distinct challenges. Maximizing the potential of these assets, and addressing local challenges, can only happen in an environment where relationships and trust provide a foundation for true partnership and collaboration. Rural Development staff understand that the legal, regulatory, governmental structure, protocols, and culture are unique to each Tribal Nation. We recognize that Tribes are distinct. We strive to understand those distinctions and tailor the delivery of services to be responsive to each Tribe’s circumstances -

The Choctaws

THE CHOCTAWS The story o f a resourceful tribe in its Oklahoma homeYakni Achnukma the Good Land By DR, A, M. GI BSON I HE EASTERN fringe of the signed, were of Muskhogean linguistic n second ('toss-Timber :, sandwiched be- This is the of a series on the Five Civilized Tribes of Okla- stock. Early in the history of tween the Canadian River and the homa by DR . ;l , M. G l BSON, Ameri-can discoveryandexplorationthey Red River is the Choctaw Country. curator of the Phillips Collection, caught the notice of Spanish, Freneh '['here nature ran riot . Tumblers land head of the manscripts division and British adventurers for their forms distorted the orderly prairie and assoc iate prof essor of history, re-markableeconomicdevelolmient,tri- plains and from the geological scram- In cooperation with Dr. Crhson, bal valor and integrity, sand their in- ble t , the Kiamichi range. the Jack F4 irk . Sooner Magazine is making re-printsavailable To obtainone, trigulng folklore. De Soto's gulf ex- Winding Stair and pine-clad Sans Bois pedition in 1540 found the Choctaws humped above theChoc taw hats. write l}r. Gibson, Manuscripts the fortified town of Division, f)1'. Sparkling waters tumbled from high- occupying Mau-bila(Mobile)andrangingacross land springs . fused into tributaries Alabama and Mississippi . Thr Choc- and in lowlands formed the Mountain trapper's paradise . taws managed to stay free of Spanish Fork, the Kiamichi and the flue. In the Choctaw language there are involvement . These rivers cut deep and their banks two words: Alukko, meaning haven Before the impact of Western civil- were lacers with oak . -

71-28823 BADGER, Herbert Andrew, 1935- A

71-28,823 BADGER, Herbert Andrew, 1935- A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW. University of Southern Mississippi, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, linguistics University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHT BY HERBERT ANDREW BADGER 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. University of Southern Mississippi A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW by Herbert Andrew Badger A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: Director Dean of tfte Graduate School May, 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW by Herbert Andrew Badger May, 1971 The justification for a grammar of Mississippi Choctaw is contingent upon two factors. First, the forced removal of the Choctaws to Oklahoma following the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek had important linguistic effects, for while the larger part of the Choctaws removed to the West where their language probably followed its natural course, there remained in Mississippi a relatively small segment of Choctaws who, because they were fugitives from the removal, were fragmented into small, isolated bands. Thus, communication between the two groups and between the isolated bands of Mississippi Choctaws was extremely limited, resulting in a significant difference between the languages of the two groups. Second, the only grammar of Choctaw, Cyrus Byington's early nineteenth cen tury Grammar of the Choctaw Language, is inadequate because it was written before descriptive linguistic science was formalized, because it reflected the Choctaw language just 1 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

A History by the Decade, 1840-1850

ITI FABVSSA A New Chahta Homeland: A History by the Decade, 1840-1850 Over the next year and a half, Iti Fabvssa is running a series that covers Oklahoma Choctaw history. By examining each decade since the Choctaw government arrived in our new homelands using Choctaw-created documents, we will get a better understanding of Choctaw ancestors’ experiences and how they made decisions that have led us into the present. This month, we will be covering 1840-1850, a period when Choctaws dealt with the complications of incorporating Chickasaws into their territory, two new constitutions and the expansion of its economy and school system. At the start of the 1830s, Choctaws began the process of removal to their new homeland. In 1837, they had to deal with another difficulty– that of the Chickasaw Removal. The Chickasaw Nation would be removed into the Choctaw Nation when they arrived in Indian Territory. In working to resolve this new, complex issue, Choctaws and Chickasaws passed a new constitution in 1838 that brought the two nations together under one government. Although Choctaws and Chickasaws were united under this constitution, the newly created Chickasaw District maintained its own financial separation. Another significant feature of the Choctaw- Chickasaw relationship was that they had to share ownership over the entire territory that Choctaw Nation had previously received by treaty with the US government. This meant that the two tribes had to agree and work together when negotiating with the U.S. government – a provision that is still in effect today when it comes to issues over land and water. -

Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Volume 15

Library of Congress Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Volume 15 Cutting Marsh (From photograph loaned by John N. Davidson.) Wisconsin State historical society. COLLECTIONS OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY. OF WISCONSIN EDITED AND ANNOTATED BY REUBEN GOLD THWAITES Secretary and Superintendent of the Society VOL. XV Published by Authority of Law MADISON DEMOCRAT PRINTING COMPANY, STATE PRINTER 1900 LC F576 .W81 2d set The Editor, both for the Society and for himself, disclaims responsibility for any statement made either in the historical documents published herein, or in articles contributed to this volume. 1036011 18 N43 LC CONTENTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS. Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Volume 15 http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.7689d Library of Congress THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SERIAL RECORD NOV 22 1943 Copy 2 Page. Cutting Marsh Frontispiece. Officers of the Society, 1900 v Preface vii Some Wisconsin Indian Conveyances, 1793–1836. Introduction The Editor 1 Illustrative Documents: Land Cessions—To Dominique Ducharme, 1; to Jacob Franks, 3; to Stockbridge and Brothertown Indians, 6; to Charles Grignon, 19. Milling Sites—At Wisconsin River Rapids, 9; at Little Chute, 11; at Doty's Island, 14; on west shore of Green Bay, 16; on Waubunkeesippe River, 18. Miscellaneous—Contract to build a house, 4; treaty with Oneidas, 20. Illustrations: Totems—Accompanying Indian signatures, 2, 3, 4. Sketch of Cutting Marsh. John E. Chapin, D. D. 25 Documents Relating to the Stockbridge Mission, 1825–48. Notes by William Ward Wight and The Editor. 39 Illustrative Documents: Grant—Of Statesburg mission site, 39. Letters — Jesse Miner to Stockbridges, 41; Jeremiah Evarts to Miner, 43; [Augustus T. -

2016 Maupin Matthew Thesis

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE CROSS CULTURAL MEDICAL AND NATURAL KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE ON THE MISSISSIPPI FRONTIER BETWEEN GIDEON LINCECUM AND THE CHOCTAW NATION: 1818 TO 1833 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY OF SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MEDICINE By MATTHEW KIRK MAUPIN Norman, Oklahoma 2016 CROSS CULTURAL MEDICAL AND NATURAL KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE ON THE MISSISSIPPI FRONTIER BETWEEN GIDEON LINCECUM AND THE CHOCTAW NATION: 1818 TO 1833 A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF SCIENCE BY ______________________________ Dr. Suzanne Moon, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Kathleen Crowther ______________________________ Dr. Peter Soppelsa ______________________________ Dr. Joe Watkins © Copyright by MATTHEW KIRK MAUPIN 2016 All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Table of Contents ...............................................................................................iv Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………vi Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 Narrowing the Focus ....................................................................................... 3 Gideon Lincecum ............................................................................................ 4 Historiography ................................................................................................. 8 Chapter Outline ............................................................................................ -

Neither Slave Nor Free... : Interracial Ecclesiastical Interaction in Presbyterian Mission Churches from South Carolina to Mississippi, 1818-1877

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Neither Slave Nor Free... : Interracial Ecclesiastical Interaction In Presbyterian Mission Churches From South Carolina To Mississippi, 1818-1877. Otis Westbrook Pickett University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Pickett, Otis Westbrook, "Neither Slave Nor Free... : Interracial Ecclesiastical Interaction In Presbyterian Mission Churches From South Carolina To Mississippi, 1818-1877." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 638. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/638 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “NEITHER SLAVE NOR FREE…” : INTERRACIAL ECCLESIASTICAL INTERACTION IN PRESBYTERIAN MISSION CHURCHES FROM SOUTH CAROLINA TO MISSISSIPPI, 1818-1877. A Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of History The University of Mississippi by By Otis Westbrook Pickett May 2013 Copyright Otis W. Pickett 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This research focuses on the efforts of a variety of missionary agencies, organizations, Presbyteries, synods and congregations who pursued domestic missionary efforts and established mission churches among enslaved Africans and Native Americans from South Carolina to Mississippi from 1818-1877. The dissertation begins with a historiographical overview of southern religion among whites, enslaved Africans and Native Americans. It then follows the work of the Rev. Cyrus Kingsbury among the Choctaw, the Rev. T.C. -

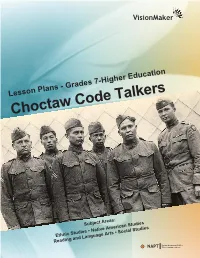

Choctaw Code Talkers

VisionMaker Lesson Plans - Grades 7-Higher Education Choctaw Code Talkers Subject Areas: Ethnic Studies • Native American Studies Reading and Language Arts • Social Studies NAPT Native American Public Telecommunications VisionMaker Procedural Notes for Educators Film Synopsis In 1918, not yet citizens of the United States, Choctaw men of the American Expeditionary Forces were asked to use their Native language as a powerful tool against the German Forces in World War I, setting a precedent for code talking as an effective military weapon and establishing them as America's original Code Talkers. A Note to Educators These lesson plans are created for students in grades 7 through higher education. Each lesson can be adapted to meet your needs. Robert S. Frazier, grandfather of Code Talker Tobias Frazier, and sheriff of Jack's Fork and Cedar Counties Image courtesy of "Choctaw Code Talkers" Native American Public 2 NAPT Telecommunications VisionMaker Objectives and Curriculum Standards a. Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, Objectives paragraph, or text; a word’s position or function in a sentence) These activities are designed to give participants as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase. learning experiences that will help them understand and b. Identify and correctly use patterns of word changes that indicate different meanings or parts of speech. consider the history of the sovereign Choctaw Nation c. Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., of Oklahoma, and its unique relationship to the United dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to States of America; specifically how that relates to the find the pronunciation of words, a word or determine or clarify documentary, Choctaw Code Talkers. -

Newsletter Xxvi:2

THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF THE INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES OF THE AMERICAS NEWSLETTER XXVI:2 July-September 2007 Published quarterly by the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Lan- SSILA BUSINESS guages of the Americas, Inc. Editor: Victor Golla, Dept. of Anthropology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521 (e-mail: golla@ ssila.org; web: www.ssila.org). ISSN 1046-4476. Copyright © 2007, The Chicago Meeting SSILA. Printed by Bug Press, Arcata, CA. The 2007-08 annual winter meeting of SSILA will be held on January 3-6, 2008 at the Palmer House (Hilton), Chicago, jointly with the 82nd Volume 26, Number 2 annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. Also meeting concur- rently with the LSA will be the American Dialect Society, the American Name Society, and the North American Association for the History of the CONTENTS Language Sciences. The Palmer House has reserved blocks of rooms for those attending the SSILA Business . 1 2008 meeting. All guest rooms offer high speed internet, coffee makers, Correspondence . 3 hairdryers, CD players, and personalized in-room listening (suitable for Obituaries . 4 iPods). The charge for (wired) in-room high-speed internet access is $9.95 News and Announcements . 9 per 24 hours; there are no wireless connections in any of the sleeping Media Watch . 11 rooms. (The lobby and coffee shop are wireless areas; internet access costs News from Regional Groups . 12 $5.95 per hour.) The special LSA room rate (for one or two double beds) Recent Publications . 15 is $104. The Hilton reservation telephone numbers are 312-726-7500 and 1-800-HILTONS. -

Slaves and Slaveholders in the Choctaw Nation: 1830-1866

SLAVES AND SLAVEHOLDERS IN THE CHOCTAW NATION: 1830-1866 Jeffrey L. Fortney , Jr., B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2009 APPROVED: D. Harland Haglen, Major Professor Randolph Campbell, Committee Member F. Todd Smith, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Michael Monticino, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Fortney Jr., Jeffrey L. Slaves and Slaveholders in the Choctaw Nation: 1830-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2009, 71 pp., 5 tables, 4 figures, bibliography, 46 titles. Racial slavery was a critical element in the cultural development of the Choctaws and was a derivative of the peculiar institution in southern states. The idea of genial and hospitable slave owners can no more be conclusively demonstrated for the Choctaws than for the antebellum South. The participation of Choctaws in the Civil War and formal alliance with the Confederacy was dominantly influenced by the slaveholding and a connection with southern identity, but was also influenced by financial concerns and an inability to remain neutral than a protection of the peculiar institution. Had the Civil War not taken place, the rate of Choctaw slave ownership possibly would have reached the level of southern states and the Choctaws would be considered part of the South. Copyright 2009 by Jeffrey L. Fortney, Jr. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ -

Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in This Edition of Newspapers in Education

he American Indian Cultural Center and Museum (AICCM) is honored Halito! Oklahoma has a unique history that differentiates it from any other Tto present, in partnership with Newspapers In Education at The Oklahoman, state in the nation. Nowhere else in the United States can a visitor hear first the Native American Heritage educational workbook. Workbooks focus on hand-accounts from 39 different American Indian Tribal Nations regarding the cultures, histories and governments of the American Indian tribes of their journey from ancestral homelands, or discover how Native peoples have Oklahoma. The workbooks are published twice a year, around November contributed and woven their identities into the fabric of contemporary Oklahoma. and April. Each workbook is organized into four core thematic areas: Origins, Oklahoma is deeply rooted in American Indian history and heritage. We hope Native Knowledge, Community and Governance. Because it is impossible you will use this guide to explore our great state and to learn about Okla- to cover every aspect of the topics featured in each edition, we hope the Humma. (“Red People” in the Choctaw language.)–Gena Timberman, Esq., workbooks will comprehensively introduce students to a variety of new subjects and ideas. We hope you will be inspired to research and find out more information with the help of your teachers and parents as well as through your own independent research. The American Indian Cultural Center and Museum would like to give special thanks to the Oklahoma Tourism & Recreation Department for generously permitting us to share information featured in the Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in this edition of Newspapers in Education. -

The Chickasaw Nation, Muscogee Creek Nation, Sac & Fox Nation, and Choctaw Nation Present

The Chickasaw Nation, Muscogee Creek Nation, Sac & Fox Nation, and Choctaw Nation present NATIVE AMERICAN Language & Culture Newspapers for this educational program provided by: Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 List of Tribes in Oklahoma ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Chickasaw Nation ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................5-8 Sac & Fox Nation ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................9-13 Choctaw Nation ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................14-18