71-28823 BADGER, Herbert Andrew, 1935- A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborating for Prosperity with American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities

Collaborating for Prosperity With American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities USDA Rural Development Innovation Center Together, America Prospers From 2001 to 2018 USDA Rural Development invested more than $6.2 billion in Indian Country and Alaska. USDA Rural Development places a high value on its relationship with Tribes, American Indians, and Alaska Natives. We are committed to increasing investment throughout Indian Country and Alaska. We are collaborating and partnering with Tribes to realize a brighter future for families, children, and Tribal communities. Through loans, grants, and technical assistance, Rural Development makes critical investments in infrastructure, schools, health clinics, housing, and businesses, to benefit Native families and communities across rural America. Rural Development supports American Indians and Alaska Natives in holistic, sustainable, and culturally responsive ways. Every Tribal Nation has unique assets and faces distinct challenges. Maximizing the potential of these assets, and addressing local challenges, can only happen in an environment where relationships and trust provide a foundation for true partnership and collaboration. Rural Development staff understand that the legal, regulatory, governmental structure, protocols, and culture are unique to each Tribal Nation. We recognize that Tribes are distinct. We strive to understand those distinctions and tailor the delivery of services to be responsive to each Tribe’s circumstances -

Chahta Anumpa: a Multimodal Corpus of the Choctaw Language

Chahta Anumpa: A Multimodal Corpus of the Choctaw Language Jacqueline Brixey, Eli Pincus, Ron Artstein USC Institute for Creative Technologies 12015 E Waterfront Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90094 {brixey, pincus, artstein}@ict.usc.edu Abstract This paper presents a general use corpus for the Native American indigenous language Choctaw. The corpus contains audio, video, and text resources, with many texts also translated in English. The Oklahoma Choctaw and the Mississippi Choctaw variants of the language are represented in the corpus. The data set provides documentation support for the threatened language, and allows researchers and language teachers access to a diverse collection of resources. Keywords: endangered languages, indigenous language, multimodal, Choctaw, Native American languages 1. Introduction not abundant. The goal of this database is thus to first pre- This paper introduces a general use corpus for Choctaw, an serve a threatened language. The second contribution is to American indigenous language. The Choctaw language is compile a comprehensive data set of existing resources for spoken by the Choctaw tribe, who originally inhabited the novel research opportunities in history, linguistics, and nat- southeastern United States. The tribe is the fourth largest ural language processing. The final contribution is to pro- indigenous group by population in the United States with vide documentation of the language for language learners 220,000 enrolled members.1 The Choctaw language, how- and teachers, in order to assist in revitalization efforts. ever, is classified as “Threatened” by Ethnologue,2 as there are only 10,400 fluent speakers and the language is losing 2. Choctaw tribe and language users. 2.1. -

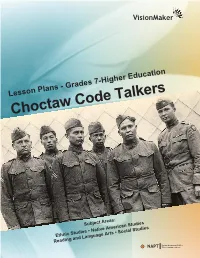

Choctaw Code Talkers

VisionMaker Lesson Plans - Grades 7-Higher Education Choctaw Code Talkers Subject Areas: Ethnic Studies • Native American Studies Reading and Language Arts • Social Studies NAPT Native American Public Telecommunications VisionMaker Procedural Notes for Educators Film Synopsis In 1918, not yet citizens of the United States, Choctaw men of the American Expeditionary Forces were asked to use their Native language as a powerful tool against the German Forces in World War I, setting a precedent for code talking as an effective military weapon and establishing them as America's original Code Talkers. A Note to Educators These lesson plans are created for students in grades 7 through higher education. Each lesson can be adapted to meet your needs. Robert S. Frazier, grandfather of Code Talker Tobias Frazier, and sheriff of Jack's Fork and Cedar Counties Image courtesy of "Choctaw Code Talkers" Native American Public 2 NAPT Telecommunications VisionMaker Objectives and Curriculum Standards a. Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, Objectives paragraph, or text; a word’s position or function in a sentence) These activities are designed to give participants as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase. learning experiences that will help them understand and b. Identify and correctly use patterns of word changes that indicate different meanings or parts of speech. consider the history of the sovereign Choctaw Nation c. Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., of Oklahoma, and its unique relationship to the United dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to States of America; specifically how that relates to the find the pronunciation of words, a word or determine or clarify documentary, Choctaw Code Talkers. -

Newsletter Xxvi:2

THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF THE INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES OF THE AMERICAS NEWSLETTER XXVI:2 July-September 2007 Published quarterly by the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Lan- SSILA BUSINESS guages of the Americas, Inc. Editor: Victor Golla, Dept. of Anthropology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521 (e-mail: golla@ ssila.org; web: www.ssila.org). ISSN 1046-4476. Copyright © 2007, The Chicago Meeting SSILA. Printed by Bug Press, Arcata, CA. The 2007-08 annual winter meeting of SSILA will be held on January 3-6, 2008 at the Palmer House (Hilton), Chicago, jointly with the 82nd Volume 26, Number 2 annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. Also meeting concur- rently with the LSA will be the American Dialect Society, the American Name Society, and the North American Association for the History of the CONTENTS Language Sciences. The Palmer House has reserved blocks of rooms for those attending the SSILA Business . 1 2008 meeting. All guest rooms offer high speed internet, coffee makers, Correspondence . 3 hairdryers, CD players, and personalized in-room listening (suitable for Obituaries . 4 iPods). The charge for (wired) in-room high-speed internet access is $9.95 News and Announcements . 9 per 24 hours; there are no wireless connections in any of the sleeping Media Watch . 11 rooms. (The lobby and coffee shop are wireless areas; internet access costs News from Regional Groups . 12 $5.95 per hour.) The special LSA room rate (for one or two double beds) Recent Publications . 15 is $104. The Hilton reservation telephone numbers are 312-726-7500 and 1-800-HILTONS. -

Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in This Edition of Newspapers in Education

he American Indian Cultural Center and Museum (AICCM) is honored Halito! Oklahoma has a unique history that differentiates it from any other Tto present, in partnership with Newspapers In Education at The Oklahoman, state in the nation. Nowhere else in the United States can a visitor hear first the Native American Heritage educational workbook. Workbooks focus on hand-accounts from 39 different American Indian Tribal Nations regarding the cultures, histories and governments of the American Indian tribes of their journey from ancestral homelands, or discover how Native peoples have Oklahoma. The workbooks are published twice a year, around November contributed and woven their identities into the fabric of contemporary Oklahoma. and April. Each workbook is organized into four core thematic areas: Origins, Oklahoma is deeply rooted in American Indian history and heritage. We hope Native Knowledge, Community and Governance. Because it is impossible you will use this guide to explore our great state and to learn about Okla- to cover every aspect of the topics featured in each edition, we hope the Humma. (“Red People” in the Choctaw language.)–Gena Timberman, Esq., workbooks will comprehensively introduce students to a variety of new subjects and ideas. We hope you will be inspired to research and find out more information with the help of your teachers and parents as well as through your own independent research. The American Indian Cultural Center and Museum would like to give special thanks to the Oklahoma Tourism & Recreation Department for generously permitting us to share information featured in the Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in this edition of Newspapers in Education. -

The Chickasaw Nation, Muscogee Creek Nation, Sac & Fox Nation, and Choctaw Nation Present

The Chickasaw Nation, Muscogee Creek Nation, Sac & Fox Nation, and Choctaw Nation present NATIVE AMERICAN Language & Culture Newspapers for this educational program provided by: Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 List of Tribes in Oklahoma ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Chickasaw Nation ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................5-8 Sac & Fox Nation ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................9-13 Choctaw Nation ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................14-18 -

MONTGOMERY-ANDERSON-A Reference Grammar of Oklahoma Cherokee

A REFERENCE GRAMMAR OF OKLAHOMA CHEROKEE Brad Montgomery-Anderson B.A., University of Colorado, 1993 M.A., University of Illinois at Chicago, 1996 Submitted to the Linguistics Program and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dr. Akira Yamamoto, Chair Dr. Clifton Pye Dr. Anita Herzfeld Dr. Harold Torrence Dr. Lizette Peter Date Defended: May 30, 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Brad Montgomery-Anderson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A REFERENCE GRAMMAR OF OKLAHOMA CHEROKEE BY Copyright 2008 Brad Montgomery-Anderson Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date Approved: May 30, 2008 ii ABSTRACT The majority of Native American Languages are threatened with extinction within the next 100 years, a loss that will entail the destruction of the unique cultural identity of the peoples that speak them. This dissertation is a reference grammar of one such language, the Cherokee language of Oklahoma. Cherokee is the sole member of the southern branch of the Iroquoian language family. If current trends continue, it will cease to exist as a living language in two generations. Among the three federally-recognized tribes there is a strong commitment to language revitalization; furthermore, there is a large number of active speakers compared to other Native American languages. This current work aims to serve as a reference work for Cherokees interested in learning about the grammar of their language as well as for educators who are developing language materials. This dissertation also offers the academic community a comprehensive descriptive presentation of the phonology, morphology, and syntax of the language. -

Developing Sovereignty: Choctaw Reconfigurations of Culture and Politics Through Econom

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles (Re)Developing Sovereignty: Choctaw Reconfigurations of Culture and Politics through Economic Development in Oklahoma A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in American Indian Studies by Megan Alexandria Baker 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS (Re)Developing Sovereignty: Choctaw Reconfigurations of Culture and Politics through Economic Development in Oklahoma by Megan Alexandria Baker Master of Arts in American Indian Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Jessica R. Cattelino, Chair To counteract their historical erasure and economic marginalization within American settler society, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma repurposes economic development robustly. Choctaw sovereignty, reinvigorated by economic development, enables the Nation to assert their political presence in ways that have transformed southeastern Oklahoma economically. Ethnographic examination of Chahta Anumpa Aiikhvna (School of Choctaw Language) and the history of Chahta anumpa (Choctaw language) in Oklahoma demonstrates how Choctaw Nation has accomplished both of these things. Additionally, this thesis critically examines Choctaw citizens’ complex experiences with economic development, which are shaped by a continual process of ii Indigenous dispossession. Understanding how these experiences and histories link together in turn opens up alternative possibilities for Choctaw futures grounded in Choctaw ways of life. iii The thesis of Megan Alexandria Baker is approved. -

Argument Structure and Argument-Marking in Choctaw

Abstract Argument Structure and Argument-marking in Choctaw Matthew Tyler 2020 This thesis examines argument structure—the linking relations between verbs and their arguments—in Choctaw, a Muskogean language spoken in Mississippi and Oklahoma. My focus is on three morphological reflexes of argument structure, which constitute the argument-marking systems of the title. Firstly, the verb may host various morphological markers of voice, which often carry labels like ‘transitive’ or ‘causative’. Secondly, the verb may host clitics which index (or ‘double’) certain arguments. Thirdly, overt arguments may carry case-markers. Following recent work in Minimalism and Distributed Morphology, I argue that each of these morphological systems is ‘read off’ a syntactic structure, which encodes verbal argument structure through a root and an arrangement of functional heads (v, Voice, Appl). This syntactic structure must make use of, at least, trivalent specifier requirements, in the sense of Kastner (2020), and a licensing relation. And in the mappings from syntactic structure to morphological and semantic output, there must be a high degree of contextual conditioning, in the sense of Wood and Marantz (2017). Of particular relevance to the syntax- morphology interface, I argue that case-assignment is morphological, and subject to contextual conditioning in the same way that morphological exponence is. I first discuss voice morphology, focusing on the (anti)causative alternation and syntactic causatives. I concentrate on some key puzzles, concerning the multifunctionality of several pieces of morphology. Upon inspection, there turns out to be a many-to-many correspondence between syntactic behavior, morphologi- cal exponence, and interpretation. To account for this I adopt two innovations. -

The Lower Mississippi Valley As a Language Area

The Lower Mississippi Valley as a Language Area By David V. Kaufman Submitted to the graduate degree program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Carlos M Nash ________________________________ Bartholomew Dean ________________________________ Clifton Pye ________________________________ Harold Torrence ________________________________ Andrew McKenzie Date Defended: May 30, 2014 ii The Dissertation Committee for David V. Kaufman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Lower Mississippi Valley as a Language Area ________________________________ Chairperson Carlos M Nash Date approved: June 9, 2014 iii Abstract It has been hypothesized that the Southeastern U.S. is a language area, or Sprachbund. However, there has been little systematic examination of the supposed features of this area. The current analysis focuses on a smaller portion of the Southeast, specifically, the Lower Mississippi Valley (LMV), and provides a systematic analysis, including the eight languages that occur in what I define as the LMV: Atakapa, Biloxi, Chitimacha, Choctaw-Chickasaw, Mobilian Trade Language (MTL), Natchez, Ofo, and Tunica. This study examines phonetic, phonological, and morphological features and ranks them according to universality and geographic extent, and lexical and semantic borrowings to assess the degree of linguistic and cultural contact. The results -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Language Ideologies and Practices Among University Learners of Native American Langua

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE LANGUAGE IDEOLOGIES AND PRACTICES AMONG UNIVERSITY LEARNERS OF NATIVE AMERICAN LANGUAGES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN APPLIED LINGUISTIC ANTHROPOLOGY By MICHAEL WILSON Norman, Oklahoma 2016 LANGUAGE IDEOLOGIES AND PRACTICES AMONG UNIVERSITY LEARNERS OF NATIVE AMERICAN LANGUAGES A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Sean O’Neill, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Racquel-María Sapién ______________________________ Dr. Misha Klein ______________________________ Dr. Gus Palmer © Copyright by MICHAEL WILSON 2016 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support of the Native American language instructors at the University of Oklahoma. I would like to sincerely thank Mrs. Christine Armer, Mr. Charles Foster, Mr. Freddie Lewis, Mr. Dane Poolaw, Mrs. Martha Poolaw, and Mr. Dillon Vaughn for welcoming me into their classrooms to conduct research. Their tireless dedication to language teaching greatly benefits hundreds of students each year, and I have the highest respect for their leadership and creativity. Wado, yakoke, and àhô to each of you! I would particularly like to thank Dr. Sean O’Neill for his ongoing guidance and support over the years. It was a great privilege to have him as the chair of my committee, and his wealth of insights continue to inspire me. I would also like to thank Dr. Raquel-María Sapién for her dedication to teaching and serving as an ideal role model for myself as well as others in my cohort. I would like to thank Dr. -

Choctaw Language Ideologies and Their Impact On

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE PURISM, PRESCRIPTIVISM, AND PRIVILEGE: CHOCTAW LANGUAGE IDEOLOGIES AND THEIR IMPACT ON TEACHING AND LEARNING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By ELIZABETH A. KICKHAM Norman, Oklahoma 2015 PURISM, PRESCRIPTIVISM, AND PRIVILEGE: CHOCTAW LANGUAGE IDEOLOGIES AND THEIR IMPACT ON TEACHING AND LEARNING A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Sean O’Neill, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Gus Palmer ______________________________ Dr. Misha Klein ______________________________ Dr. Lesley Rankin-Hill ______________________________ Dr. Marcia Haag © Copyright by ELIZABETH A. KICKHAM 2015 All Rights Reserved. For: Jamey, Sean, Rheannon, and Aidan. Just keep swimming. Acknowledgements As no work is completed in isolation, several entities and individuals deserve recognition for their support of this research. First, and foremost, I would like to thank the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and the Choctaw Language Department, specifically, for graciously allowing me to conduct this research. I want to specifically thank Joy Culbreath, Executive Director of Education at Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and James Parrish, Director of the Choctaw Language Department, for their consideration and support throughout the research process. I would also like to acknowledge the National Science Foundation and Documenting Endangered Languages for supporting this work through a Dissertation Improvement Grant (1061588), which funded the fieldwork process. The University of Oklahoma Department of Anthropology also deserves appreciation for supporting preliminary research through the Bell Research Grant and later conference travel to present and refine findings and analysis through the Opler Memorial Travel Grant. The University of Oklahoma Women’s and Gender Studies Department supported the preliminary research for this dissertation through an Alice Mary Robertson scholarship.