Master's Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborating for Prosperity with American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities

Collaborating for Prosperity With American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities USDA Rural Development Innovation Center Together, America Prospers From 2001 to 2018 USDA Rural Development invested more than $6.2 billion in Indian Country and Alaska. USDA Rural Development places a high value on its relationship with Tribes, American Indians, and Alaska Natives. We are committed to increasing investment throughout Indian Country and Alaska. We are collaborating and partnering with Tribes to realize a brighter future for families, children, and Tribal communities. Through loans, grants, and technical assistance, Rural Development makes critical investments in infrastructure, schools, health clinics, housing, and businesses, to benefit Native families and communities across rural America. Rural Development supports American Indians and Alaska Natives in holistic, sustainable, and culturally responsive ways. Every Tribal Nation has unique assets and faces distinct challenges. Maximizing the potential of these assets, and addressing local challenges, can only happen in an environment where relationships and trust provide a foundation for true partnership and collaboration. Rural Development staff understand that the legal, regulatory, governmental structure, protocols, and culture are unique to each Tribal Nation. We recognize that Tribes are distinct. We strive to understand those distinctions and tailor the delivery of services to be responsive to each Tribe’s circumstances -

Muscogee (Creek) Nation Scholarship Foundation Program

MUSCOGEE (CREEK) NATION SCHOLARSHIP FOUNDATION PROGRAM James R. Floyd Health Care Management Scholarship Scholarship Description Chief James R. Floyd is the Principal Chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the fourth largest Tribe in the Nation with more than 80,500 citizens. James grew up in Eufaula, Oklahoma. After completing his Associates Degree at OSU in Oklahoma City he started his professional career with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Tribe, working first in Environmental Services. He became the manager of Health Services, then Director of Community Services. In these positions he implemented the tribe’s first food distribution, social services, burial assistance, and school clothing allowance programs. Chief Floyd managed the first tribal-owned hospital in the United States at Okemah, and negotiated the transfer of the Okemah, Eufaula, Sapulpa, and Okmulgee Dental clinics from Indian Health Service to Muscogee (Creek) Tribal management. Chief Floyd is a strong advocate of higher education. Chief Floyd embraced and accepted his role as Principal Chief of the Nation’s fourth-largest Native American tribe in January of 2016. Throughout his career with the Indian Health Service and the Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Chief Floyd has continued to serve Native Americans throughout the United States, while always keeping in mind how his efforts could benefit his own Creek Nation. As a pioneer in Indian Health Care, Chief Floyd has been recognized nationally for establishing outreach to Native American communities. He ensured that the first of these reimbursements agreements was established with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. He also held the first tribal veterans summit at Muskogee. -

71-28823 BADGER, Herbert Andrew, 1935- A

71-28,823 BADGER, Herbert Andrew, 1935- A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW. University of Southern Mississippi, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, linguistics University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHT BY HERBERT ANDREW BADGER 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. University of Southern Mississippi A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW by Herbert Andrew Badger A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: Director Dean of tfte Graduate School May, 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW by Herbert Andrew Badger May, 1971 The justification for a grammar of Mississippi Choctaw is contingent upon two factors. First, the forced removal of the Choctaws to Oklahoma following the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek had important linguistic effects, for while the larger part of the Choctaws removed to the West where their language probably followed its natural course, there remained in Mississippi a relatively small segment of Choctaws who, because they were fugitives from the removal, were fragmented into small, isolated bands. Thus, communication between the two groups and between the isolated bands of Mississippi Choctaws was extremely limited, resulting in a significant difference between the languages of the two groups. Second, the only grammar of Choctaw, Cyrus Byington's early nineteenth cen tury Grammar of the Choctaw Language, is inadequate because it was written before descriptive linguistic science was formalized, because it reflected the Choctaw language just 1 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Tribal and House District Boundaries

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribal Boundaries and Oklahoma House Boundaries ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 22 ! 18 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 13 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 20 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 7 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cimarron ! ! ! ! 14 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 11 ! ! Texas ! ! Harper ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! n ! ! Beaver ! ! ! ! Ottawa ! ! ! ! Kay 9 o ! Woods ! ! ! ! Grant t ! 61 ! ! ! ! ! Nowata ! ! ! ! ! 37 ! ! ! g ! ! ! ! 7 ! 2 ! ! ! ! Alfalfa ! n ! ! ! ! ! 10 ! ! 27 i ! ! ! ! ! Craig ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! h ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 26 s ! ! Osage 25 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 16 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 21 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 58 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 38 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes by House District ! 11 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Absentee Shawnee* ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Woodward ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2 ! 36 ! Apache* ! ! ! 40 ! 17 ! ! ! 5 8 ! ! ! Rogers ! ! ! ! ! Garfield ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 40 ! ! ! ! ! 3 Noble ! ! ! Caddo* ! ! Major ! ! Delaware ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! Mayes ! ! Pawnee ! ! ! 19 ! ! 2 41 ! ! ! ! ! 9 ! 4 ! 74 ! ! ! Cherokee ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ellis ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 41 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 72 ! ! ! ! ! 35 4 8 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 5 3 42 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 77 -

Chahta Anumpa: a Multimodal Corpus of the Choctaw Language

Chahta Anumpa: A Multimodal Corpus of the Choctaw Language Jacqueline Brixey, Eli Pincus, Ron Artstein USC Institute for Creative Technologies 12015 E Waterfront Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90094 {brixey, pincus, artstein}@ict.usc.edu Abstract This paper presents a general use corpus for the Native American indigenous language Choctaw. The corpus contains audio, video, and text resources, with many texts also translated in English. The Oklahoma Choctaw and the Mississippi Choctaw variants of the language are represented in the corpus. The data set provides documentation support for the threatened language, and allows researchers and language teachers access to a diverse collection of resources. Keywords: endangered languages, indigenous language, multimodal, Choctaw, Native American languages 1. Introduction not abundant. The goal of this database is thus to first pre- This paper introduces a general use corpus for Choctaw, an serve a threatened language. The second contribution is to American indigenous language. The Choctaw language is compile a comprehensive data set of existing resources for spoken by the Choctaw tribe, who originally inhabited the novel research opportunities in history, linguistics, and nat- southeastern United States. The tribe is the fourth largest ural language processing. The final contribution is to pro- indigenous group by population in the United States with vide documentation of the language for language learners 220,000 enrolled members.1 The Choctaw language, how- and teachers, in order to assist in revitalization efforts. ever, is classified as “Threatened” by Ethnologue,2 as there are only 10,400 fluent speakers and the language is losing 2. Choctaw tribe and language users. 2.1. -

NK360 1 American Indian Removal What Does It Mean to Remove a People?

American Indian Removal What Does It Mean to Remove a People? Supporting Question One: What Was the Muscogee Nation’s Experience with Removal? Featured Sources Interactive Case Study—The Removal of the Muscogee Nation: Examine primary sources, quotes, short videos, and images to better understand one nation’s experience before, during, and after removal. Student Tasks Muscogee Removal Student Outcomes KNOW The Muscogee were a powerful confederacy of southeastern tribes before the European colonization of North America. A sharply divided U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, and in the Treaty of 1832 the Muscogee finally ceded all their remaining homelands east of the Mississippi River in exchange for lands in Indian Territory. Muscogee peoples were forced to move over an 11-year period. Fifteen different groups travelled the approximately 750 miles over land and water routes, which took an average of three months to complete. Upon reaching an unfamiliar new land, the Muscogee had to build homes, reestablish their towns and government, and find ways to survive. UNDERSTAND Muscogee leaders faced increasing pressure from the United States, from the states of Georgia and Alabama, and from unscrupulous individuals to give up their lands and move west. Some of the Muscogee removal groups faced extremely harsh conditions and thousands died during removal or soon after they arrived in Indian Territory, yet the strength of Muscogee culture and beliefs and the tenacity of the people enabled them to survive both the removal and the difficult realities of their new existence. The challenges for the Muscogee people did not end with their arrival in Indian Territory. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 61/Thursday, April 1, 2021/Notices

17194 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 61 / Thursday, April 1, 2021 / Notices control of the Tennessee Valley discussed in this notice include one lot Dated: March 16, 2021. Authority, Knoxville, TN. The of whole and fragmented snail shell Melanie O’Brien, associated funerary objects were from burial 2. Manager, National NAGPRA Program. removed from archeological site 1JA305 Determinations Made by the Tennessee [FR Doc. 2021–06660 Filed 3–31–21; 8:45 am] in Jackson County, AL. BILLING CODE 4312–52–P This notice is published as part of the Valley Authority National Park Service’s administrative Officials of the Tennessee Valley responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 Authority have determined that: DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S.C. 3003(d)(3) and 43 CFR 10.11(d). • The determinations in this notice are Pursuant to 25 U.S.C. 3001(3)(A), National Park Service the sole responsibility of the museum, the objects described in this notice are reasonably believed to have been placed [NPS–WASO–NAGPRA–NPS0031612; institution, or Federal agency that has PPWOCRADN0–PCU00RP14.R50000] control of the associated funerary with or near individual human remains objects. The National Park Service is not at the time of death or later as part of Notice of Inventory Completion: responsible for the determinations in the death rite or ceremony. Museum of Riverside (Formerly Known this notice. • Pursuant to 25 U.S.C. 3001(2), a as the Riverside Metropolitan relationship of shared group identity Consultation Museum), Riverside, CA cannot be reasonably traced between the A detailed assessment of the associated funerary objects and any AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. -

Pum Opunvkv Pun Yvhiketv Pun Fulletv

Pum Opunvkv Pun Yvhiketv Pun Fulletv !"!"!"!" Our Language Our Songs Our Ways Note: This is a draft of a textbook. Some parts are still incomplete. We would be grateful for any comments. -Jack Martin, Margaret Mauldin, Gloria McCarty, 2003. Acknowledgments / Mvtô! These materials were prepared in 2003 at the University of Oklahoma. We are grateful to Dean Paul Bell of the College of Arts and Sciences and Pat Gilman, Chair of Anthropology, for supporting our work. We would also like to thank the many students who have studied Creek with us over the years. The alphabet 8 More on the alphabet 12 Heyv eshoccickvt ôs 'This is a book', Eshoccickvt ôwv? 'Is that a book?' 15 Heyv nâket ôwv? 'What's this?' 17 Heyv cokv cat!t ôs 'This book is red', Mv cokv hvtk!t ôwv? 'Is that book white?' 19 R"kke-mah! 'very big' 23 Cokv-h!cvt ôwis 'I am a student', Mvhayvt #ntskv? Are you a teacher? 24 Heyv cokv tokot ôs 'This is not a book' 26 Vm efv 'my dog', cvcke 'my mother': Possession 28 Likepvs 'Have a seat': Commands 31 Expressing aspect: Grades 33 Progressive aspect: The L-grade 34 Resulting states and intensives: The F- and N-grades 37 The H-grade 40 N!sis 'I'm buying' 42 N!set owis 'I am buying' 44 Overview of the sentence 45 Efv hvmken hêcis 'I see one dog': Numbers 47 Cett#t wâkkes c!! 'There's a snake!': Expressing existence 49 $h-ares 'It's on top of (something)': Locative prefixes 51 More on locative prefixes 53 Ecke tempen lîkes 'He's sitting near his mother': Locative nouns 55 L!tket owv? 'Is he/she running?' 57 Nâken h#mpetska? 'What are you eating?' 59 Letkek#t os 'He/She is not running' 61 Vyvhanis 'I'm going to go', M!car!s 'I will do it' 63 Lêtkvnks 'She ran': Expressing past time 65 Overview of the verb 66 Cvyayvk!n 'quietly': Manner adverbs 67 Mucv-ner! 'tonight': Time words 69 Expanding your vocabulary: -uce 'little' and -r"kk# 'big' 70 Cvnake 'mine' 71 Vce 'corn' vs. -

Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Support of Petitioner ______

No. 18-9526 IN THE JIMCY MCGIRT, Petitioner, v. OKLAHOMA, Respondent. _____________ On Writ of Certiorari to the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals _____________ BRIEF FOR AMICUS CURIAE MUSCOGEE (CREEK) NATION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER _____________ ROGER WILEY RIYAZ A. KANJI ATTORNEY GENERAL Counsel of Record KYLE HASKINS DAVID A. GIAMPETRONI FIRST ASSISTANT KANJI & KATZEN, PLLC ATTORNEY GENERAL 303 Detroit St., Ste 400 MUSCOGEE (CREEK) Ann Arbor, MI 48104 NATION (734) 769-5400 Post Office Box 580 [email protected] Okmulgee, OK 74447 (918) 295-9720 CORY J. ALBRIGHT PHILIP H. TINKER LYNSEY R. GAUDIOSO KANJI & KATZEN, PLLC 401 Second Ave. S., Ste 700 Seattle, WA 98104 (206) 344-8100 Counsel for Amicus Curiae Muscogee (Creek) Nation i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...............................................................1 ARGUMENT ...............................................................5 I. The United States and the Creek Nation Established a Reservation by Treaty. .............5 A. Text ........................................................5 B. Surrounding History .............................8 II. The Creek Allotment Act Preserved the Nation’s Reservation. ..................................... 11 A. Text ......................................................12 B. Surrounding History ........................... 16 C. Hitchcock and Buster ........................... 17 III. -

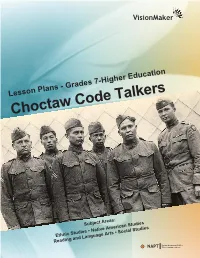

Choctaw Code Talkers

VisionMaker Lesson Plans - Grades 7-Higher Education Choctaw Code Talkers Subject Areas: Ethnic Studies • Native American Studies Reading and Language Arts • Social Studies NAPT Native American Public Telecommunications VisionMaker Procedural Notes for Educators Film Synopsis In 1918, not yet citizens of the United States, Choctaw men of the American Expeditionary Forces were asked to use their Native language as a powerful tool against the German Forces in World War I, setting a precedent for code talking as an effective military weapon and establishing them as America's original Code Talkers. A Note to Educators These lesson plans are created for students in grades 7 through higher education. Each lesson can be adapted to meet your needs. Robert S. Frazier, grandfather of Code Talker Tobias Frazier, and sheriff of Jack's Fork and Cedar Counties Image courtesy of "Choctaw Code Talkers" Native American Public 2 NAPT Telecommunications VisionMaker Objectives and Curriculum Standards a. Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, Objectives paragraph, or text; a word’s position or function in a sentence) These activities are designed to give participants as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase. learning experiences that will help them understand and b. Identify and correctly use patterns of word changes that indicate different meanings or parts of speech. consider the history of the sovereign Choctaw Nation c. Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., of Oklahoma, and its unique relationship to the United dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to States of America; specifically how that relates to the find the pronunciation of words, a word or determine or clarify documentary, Choctaw Code Talkers. -

Newsletter Xxvi:2

THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF THE INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES OF THE AMERICAS NEWSLETTER XXVI:2 July-September 2007 Published quarterly by the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Lan- SSILA BUSINESS guages of the Americas, Inc. Editor: Victor Golla, Dept. of Anthropology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521 (e-mail: golla@ ssila.org; web: www.ssila.org). ISSN 1046-4476. Copyright © 2007, The Chicago Meeting SSILA. Printed by Bug Press, Arcata, CA. The 2007-08 annual winter meeting of SSILA will be held on January 3-6, 2008 at the Palmer House (Hilton), Chicago, jointly with the 82nd Volume 26, Number 2 annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. Also meeting concur- rently with the LSA will be the American Dialect Society, the American Name Society, and the North American Association for the History of the CONTENTS Language Sciences. The Palmer House has reserved blocks of rooms for those attending the SSILA Business . 1 2008 meeting. All guest rooms offer high speed internet, coffee makers, Correspondence . 3 hairdryers, CD players, and personalized in-room listening (suitable for Obituaries . 4 iPods). The charge for (wired) in-room high-speed internet access is $9.95 News and Announcements . 9 per 24 hours; there are no wireless connections in any of the sleeping Media Watch . 11 rooms. (The lobby and coffee shop are wireless areas; internet access costs News from Regional Groups . 12 $5.95 per hour.) The special LSA room rate (for one or two double beds) Recent Publications . 15 is $104. The Hilton reservation telephone numbers are 312-726-7500 and 1-800-HILTONS. -

Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in This Edition of Newspapers in Education

he American Indian Cultural Center and Museum (AICCM) is honored Halito! Oklahoma has a unique history that differentiates it from any other Tto present, in partnership with Newspapers In Education at The Oklahoman, state in the nation. Nowhere else in the United States can a visitor hear first the Native American Heritage educational workbook. Workbooks focus on hand-accounts from 39 different American Indian Tribal Nations regarding the cultures, histories and governments of the American Indian tribes of their journey from ancestral homelands, or discover how Native peoples have Oklahoma. The workbooks are published twice a year, around November contributed and woven their identities into the fabric of contemporary Oklahoma. and April. Each workbook is organized into four core thematic areas: Origins, Oklahoma is deeply rooted in American Indian history and heritage. We hope Native Knowledge, Community and Governance. Because it is impossible you will use this guide to explore our great state and to learn about Okla- to cover every aspect of the topics featured in each edition, we hope the Humma. (“Red People” in the Choctaw language.)–Gena Timberman, Esq., workbooks will comprehensively introduce students to a variety of new subjects and ideas. We hope you will be inspired to research and find out more information with the help of your teachers and parents as well as through your own independent research. The American Indian Cultural Center and Museum would like to give special thanks to the Oklahoma Tourism & Recreation Department for generously permitting us to share information featured in the Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in this edition of Newspapers in Education.