Muskogean Languages Jack B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborating for Prosperity with American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities

Collaborating for Prosperity With American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities USDA Rural Development Innovation Center Together, America Prospers From 2001 to 2018 USDA Rural Development invested more than $6.2 billion in Indian Country and Alaska. USDA Rural Development places a high value on its relationship with Tribes, American Indians, and Alaska Natives. We are committed to increasing investment throughout Indian Country and Alaska. We are collaborating and partnering with Tribes to realize a brighter future for families, children, and Tribal communities. Through loans, grants, and technical assistance, Rural Development makes critical investments in infrastructure, schools, health clinics, housing, and businesses, to benefit Native families and communities across rural America. Rural Development supports American Indians and Alaska Natives in holistic, sustainable, and culturally responsive ways. Every Tribal Nation has unique assets and faces distinct challenges. Maximizing the potential of these assets, and addressing local challenges, can only happen in an environment where relationships and trust provide a foundation for true partnership and collaboration. Rural Development staff understand that the legal, regulatory, governmental structure, protocols, and culture are unique to each Tribal Nation. We recognize that Tribes are distinct. We strive to understand those distinctions and tailor the delivery of services to be responsive to each Tribe’s circumstances -

The Seminole Indian Wars (1814-1858)

THE SEMINOLE INDIAN WARS (1814-1858) Compiled by Brian Brindle Version 0.1 © 2013 Dadi&Piombo This supplement was designed to the cover three small American wars fought between 1814-1858 known today as the “Seminole Wars”. These Wars were primary gorilla style wars fought between the Seminole Indians and the U.S. army . The wars played out in a series of small battles and skirmishes as U.S. Army chased bands of Seminole worriers through the swamps IofN Florida. THE DARK In 1858 the U.S. declared the third war ended - though no peace treaty was ever signed. It is interesting to note that to this day the Seminole Tribe of Florida is the only native American tribe who have never signed a peace treaty with the U.S. Govern- ment. This Supplement allows for some really cool hit and run skirmishing in the dense The Seminole Wars and Vietnam are one vegetation and undergrowth of the Florida of the few confrontations that the U.S. swamps. It also allow s for small engage- Army have engaged in that they did not ments of small groups of very cunning definitively win. natives, adept in using the terrain to its best advantage fighting a larger, more HISTORICAL BACKGROUND clumsy, conventional army. In the early 18th century, bands of Muskogean-speaking Lower Creek In many ways Seminole War echoes the migrated to Florida from Georgia. They Vietnam War, both were guerrilla wars became known as the Seminole (liter- involving patrols out constantly, trying ally “separatists”). Floridian territory was to locate and eliminate an elusive enemy. -

View / Open Gregory Oregon 0171N 12796.Pdf

CHUNKEY, CAHOKIA, AND INDIGENOUS CONFLICT RESOLUTION by ANNE GREGORY A THESIS Presented to the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2020 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anne Gregory Title: Chunkey, Cahokia, and Indigenous Conflict Resolution This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program by: Kirby Brown Chair Eric Girvan Member and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2020. ii © 2020 Anne Gregory This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii THESIS ABSTRACT Anne Gregory Master of Science Conflict and Dispute Resolution June 2020 Title: Chunkey, Cahokia, and Indigenous Conflicts Resolution Chunkey, a traditional Native American sport, was a form of conflict resolution. The popular game was one of several played for millennia throughout Native North America. Indigenous communities played ball games not only for the important culture- making of sport and recreation, but also as an act of peace-building. The densely populated urban center of Cahokia, as well as its agricultural suburbs and distant trade partners, were dedicated to chunkey. Chunkey is associated with the milieu surrounding the Pax Cahokiana (1050 AD-1200 AD), an era of reduced armed conflict during the height of Mississippian civilization (1000-1500 AD). The relational framework utilized in archaeology, combined with dynamics of conflict resolution, provides a basis to explain chunkey’s cultural impact. -

Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in English of Native American Origin Found Within

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Indian origin names, were eventually shortened to one-word names, making a few indistinguishable from names of non-Indian origin. Name Categories: Personal and family names of Indian origin contrast markedly with names of non-Indian Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in origin. English of Native American Origin 1. Personal and family names from found within Marquette University Christian saints (e.g. Juan, Johnson): Archival Collections natives- rare; non-natives- common 2. Family names from jobs (e.g. Oftentimes names of Native Miller): natives- rare; non-natives- American origin are based on objects common with descriptive adjectives. The 3. Family names from places (e.g. following list, which is not Rivera): natives- rare; non-native- comprehensive, comprises common approximately 1,000 name variations in 4. Personal and family names from English found within the Marquette achievements, attributes, or incidents University archival collections. The relating to the person or an ancestor names originate from over 50 tribes (e.g. Shot with two arrows): natives- based in 15 states and Canada. Tribal yes; non-natives- yes affiliations and place of residence are 5. Personal and family names from noted. their clan or totem (e.g. White bear): natives- yes; non-natives- no History: In ancient times it was 6. Personal or family names from customary for children to be named at dreams and visions of the person or birth with a name relating to an animal an ancestor (e.g. Black elk): natives- or physical phenominon. Later males in yes; non-natives- no particular received names noting personal achievements, special Tribes/ Ethnic Groups: Names encounters, inspirations from dreams, or are expressed according to the following physical handicaps. -

Reviews R E V I E W S À À À Reviews

DOI 10.17953/aicrj.44.3.reviews R EVIEWS à à à REVIEWS Basket Diplomacy: Leadership, Alliance-Building, and Resilience among the Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/aicrj/article-pdf/44/3/91/2864733/i0161-6463-44-3-91.pdf by University of California user on 09 July 2021 Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, 1884–1984. By Denise E. Bates. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020. 354 pages. $65.00 cloth and electronic. Basket Diplomacy offers an exceptionally well-researched and detailed account of the history of the Coushatta people of Louisiana. Substantially expanding the limited literature, Denise Bates seamlessly merges archival historical research and interviews with Coushatta tribal members. Bates’s text contributes a significant examination of historical struggles relevant to Indigenous peoples throughout the southeast. Each chapter richly details the dominant issues of the late-1800s to the mid-1980s. Throughout the book, Bates describes the battle with the whims and inconsistencies of government policy changes. She contextualizes Coushatta history within the social, cultural, and historical context of Louisiana and the wider southeast. Bates shows how the Coushatta people advocated for themselves not only to survive extreme challenges but to become major actors on the Louisiana political and economic stage. In the process, Bates takes an insightful view towards cultural continuity and change, empha- sizing creative ways the Coushatta people adapted while maintaining cultural integrity. Her account of the Coushatta church, for example, foregrounds Coushatta views on Christianity and the central role the church played in their community to bring people together and preserve the Koasati language. The author provides a brief overview of Coushatta involvement in the Creek Confederacy and their early migrations to Louisiana, providing ample resources for additional research. -

Muscogee (Creek) Nation Scholarship Foundation Program

MUSCOGEE (CREEK) NATION SCHOLARSHIP FOUNDATION PROGRAM James R. Floyd Health Care Management Scholarship Scholarship Description Chief James R. Floyd is the Principal Chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the fourth largest Tribe in the Nation with more than 80,500 citizens. James grew up in Eufaula, Oklahoma. After completing his Associates Degree at OSU in Oklahoma City he started his professional career with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Tribe, working first in Environmental Services. He became the manager of Health Services, then Director of Community Services. In these positions he implemented the tribe’s first food distribution, social services, burial assistance, and school clothing allowance programs. Chief Floyd managed the first tribal-owned hospital in the United States at Okemah, and negotiated the transfer of the Okemah, Eufaula, Sapulpa, and Okmulgee Dental clinics from Indian Health Service to Muscogee (Creek) Tribal management. Chief Floyd is a strong advocate of higher education. Chief Floyd embraced and accepted his role as Principal Chief of the Nation’s fourth-largest Native American tribe in January of 2016. Throughout his career with the Indian Health Service and the Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Chief Floyd has continued to serve Native Americans throughout the United States, while always keeping in mind how his efforts could benefit his own Creek Nation. As a pioneer in Indian Health Care, Chief Floyd has been recognized nationally for establishing outreach to Native American communities. He ensured that the first of these reimbursements agreements was established with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. He also held the first tribal veterans summit at Muskogee. -

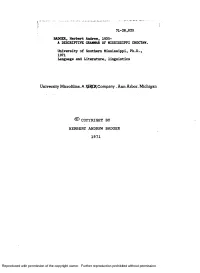

71-28823 BADGER, Herbert Andrew, 1935- A

71-28,823 BADGER, Herbert Andrew, 1935- A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW. University of Southern Mississippi, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, linguistics University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHT BY HERBERT ANDREW BADGER 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. University of Southern Mississippi A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW by Herbert Andrew Badger A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: Director Dean of tfte Graduate School May, 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW by Herbert Andrew Badger May, 1971 The justification for a grammar of Mississippi Choctaw is contingent upon two factors. First, the forced removal of the Choctaws to Oklahoma following the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek had important linguistic effects, for while the larger part of the Choctaws removed to the West where their language probably followed its natural course, there remained in Mississippi a relatively small segment of Choctaws who, because they were fugitives from the removal, were fragmented into small, isolated bands. Thus, communication between the two groups and between the isolated bands of Mississippi Choctaws was extremely limited, resulting in a significant difference between the languages of the two groups. Second, the only grammar of Choctaw, Cyrus Byington's early nineteenth cen tury Grammar of the Choctaw Language, is inadequate because it was written before descriptive linguistic science was formalized, because it reflected the Choctaw language just 1 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

PETITION Ror,RECOGNITION of the FLORIDA TRIBE Or EASTERN CREEK INDIANS

'l PETITION rOR,RECOGNITION OF THE FLORIDA TRIBE or EASTERN CREEK INDIANS TH;: FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS and the Administra tive Council, THE NORTHWEST FLORIDA CREEK INDIAN COUNCIL brings this, thew petition to the DEPARTMENT Or THE INTERIOR OF THE FEDERAL GOVERN- MENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, and prays this honorable nation will honor their petition, which is a petition for recognition by this great nation that THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS is an Indian Tribe. In support of this plea for recognition THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS herewith avers: (1) THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS nor any of its members, is the subject of Congressional legislation which has expressly terminated or forbidden the Federal relationship sought. (2) The membership of THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS is composed principally of persons who are not members of any other North American Indian tribe. (3) A list of all known current members of THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS, based on the tribes acceptance of these members and the tribes own defined membership criteria is attached to this petition and made a part of it. SEE APPENDIX----- A The membership consists of individuals who are descendants of the CREEK NATION which existed in aboriginal times, using and occuping this present georgraphical location alone, and in conjunction with other people since that time. - l - MNF-PFD-V001-D0002 Page 1of4 (4) Attached herewith and made a part of this petition is the present governing Constitution of THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEKS INDIANS. -

Trailword.Pdf

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. _X___ New Submission ____ Amended Submission ======================================================================================================= A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ======================================================================================================= Historic and Historical Archaeological Resources of the Cherokee Trail of Tears ======================================================================================================= B. Associated Historic Contexts ======================================================================================================= (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) See Continuation Sheet ======================================================================================================= C. Form Prepared by ======================================================================================================= -

Tribal and House District Boundaries

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribal Boundaries and Oklahoma House Boundaries ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 22 ! 18 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 13 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 20 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 7 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cimarron ! ! ! ! 14 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 11 ! ! Texas ! ! Harper ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! n ! ! Beaver ! ! ! ! Ottawa ! ! ! ! Kay 9 o ! Woods ! ! ! ! Grant t ! 61 ! ! ! ! ! Nowata ! ! ! ! ! 37 ! ! ! g ! ! ! ! 7 ! 2 ! ! ! ! Alfalfa ! n ! ! ! ! ! 10 ! ! 27 i ! ! ! ! ! Craig ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! h ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 26 s ! ! Osage 25 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 16 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 21 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 58 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 38 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes by House District ! 11 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Absentee Shawnee* ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Woodward ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2 ! 36 ! Apache* ! ! ! 40 ! 17 ! ! ! 5 8 ! ! ! Rogers ! ! ! ! ! Garfield ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 40 ! ! ! ! ! 3 Noble ! ! ! Caddo* ! ! Major ! ! Delaware ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! Mayes ! ! Pawnee ! ! ! 19 ! ! 2 41 ! ! ! ! ! 9 ! 4 ! 74 ! ! ! Cherokee ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ellis ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 41 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 72 ! ! ! ! ! 35 4 8 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 5 3 42 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 77 -

Introduction

xix Introduction In 1936, at the age of just 26, Mary R. Haas moved from New Haven, Connecticut to Eufaula, Oklahoma to begin a study of the Creek (Muskogee) language. It was the height of the Great Depression and Dust Bowl, and jobs were scarce, but with help from former teachers Haas found meager support for her research until the threat of war in 1941. The texts in this volume are a result of that project. About Mary R. Haas Mary R. Haas was born January 23, 1910 in Richmond, Indiana to Robert Jeremiah Haas and Leona Crowe Haas.1 She received three years of tuition scholarships at Earlham College, where she studied English.2 She also received a scholarship in music during her final year and graduated at the head of her class in 1930.3 She entered graduate school in the Department of Comparative Philology at the University of Chicago the same year. There she studied Gothic, Old High German with Leonard Bloomfield, Sanskrit, and Psychology of Language with Edward Sapir.4 She also met and married her fellow student Morris Swadesh. The two traveled to British Columbia after their first year to work on Nitinat, and then followed Sapir to Yale University’s Department of Linguistics in 1931. She continued her studies there of Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit and took two courses in Primitive Music.5 Haas worked as Sapir’s research assistant from 1931 to 1933.6 In the summer of 1933, she received funding to conduct field work in Louisiana with the last speaker of Tunica, close to where Swadesh was working on Chitimacha.7 Haas’s next project was the Natchez language of eastern Oklahoma. -

“The Golden Days”: Taylor and Mary Ealy, Citizenship, and the Freedmen of Chickasaw Indian Territory, 1874–77

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA “The Golden Days”: Taylor and Mary Ealy, Citizenship, and the Freedmen of Chickasaw Indian Territory, 1874–77 By Ellen Cain* On a Monday morning in fall 1874, twenty-six-year- old Taylor Ealy felt despondent. He had recently completed an ambi- tious educational program that included college, seminary, and medi- cal school, yet he was confused about the direction of his future. He longed for the bold, adventurous life of a Presbyterian missionary, not the tame existence he now led as a Pennsylvania preacher. Ealy went to his room on that Monday morning, dropped to his knees, and prayed, “Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do—send me anywhere. Show me my work.” The answer came swiftly, the very same day, Ealy received a letter asking him to appear before the Northern Presbyterian Freed- men’s Bureau in Pittsburgh. When he arrived, the secretary of the bureau offered him a choice: to teach at a nearby theological seminary or at a government school for freedmen at Fort Arbuckle, Chickasaw Indian Territory (present-day south-central Oklahoma). Ealy knew immediately that he wanted the more challenging position in the West. 54 “THE GOLDEN DAYS” “I said I will take the harder field. I looked upon this as a direct answer to my prayer.”1 So it was that Taylor Ealy and his new bride, Mary Ramsey, set out for Indian Territory in October 1874. The Ealys carried with them a sincere and enthusiastic desire to aid the recently freed black slaves of the Chickasaw Nation. They labored in Indian Territory—a land of former Confederates—during the last years of Reconstruction.