A New Identity for a Prosperous Future? 42Nd Isocarp Congress 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predstavljamo Eagle Hills

PRONAĐI SIGURNO MESTO OVI TEMELJI SU TVOJI KORENI, TVOJA VEZA SA ONIMA KOJE VOLIŠ. OVI ZIDOVI SU TVOJ OSLONAC. MEĐU NJIMA ŽIVE SVI TRENUCI SREĆE. OVI PROZORI SU TVOJA KRILA. TVOJ POGLED U BUDUĆNOST. BW TERRA - MESTO KOJEM PRIPADAŠ. FIND A SAFE PLACE THESE FOUNDATIONS ARE YOUR ROOTS. YOUR CONNECTION TO THOSE WHO YOU LOVE. THESE WALLS ARE YOUR BACKBONE. AMONG THEM LIVE, YOUR MOMENTS OF HAPPINESS. THESE WINDOWS ARE YOUR WINGS.YOUR PERSPECTIVE ON THE FUTURE. BW TERRA – THE PLACE WHERE YOU BELONG. SADRŽAJCONTENT MESTO ZA BUDUĆNOST3 YOUR FUTURE PLACE — 03-08 BELI GRAD ŽIVOT U 1WHITE CITY 4 — 03-08 IZOBILJU THE LAND OF PLENTY — 03-08 2 VELIČANSTVENA PREDSTAVLJAMO OBALA EAGLE5 HILLS SUPERB RIVERSIDE DESTINATION INTRODUCING EAGLE HILLS — — 03-08 03-08 2 BELI GRAD WHITE CITY 1 1 | BELI GRAD SRCE I DUŠA REGIONATHE REGION’S HEART AND SOUL Sa svojom jedinstvenom lokacijom na ušću dveju velikih Uniquely located at the confluence of two major rivers, reka, Save i Dunava, Beograd, ili „Beli Grad”, kako su ga the Sava and the Danube, Belgrade, or “White City”, as zvali stari slovenski narodi koji su nastanili ovaj region u it was named by the old Slavic people who settled the th 7. veku nove ere, vekovima uspešno spaja uticaje istoka region in the 7 century AD, has been blending eastern i zapada. Glavni grad Srbije je mozaik različitih kultura and western influences for centuries. The Serbian capital i stilova, poznat po svojoj bogatoj istoriji, živoj kulturnoj is a mosaic of divergent cultures and styles, famous for sceni, dinamičnom noćnom životu i kosmopolitskom duhu. -

Disillusioned Serbians Head for China's Promised Land

Serbians now live and work in China, mostly in large cities like Beijing andShanghai(pictured). cities like inlarge inChina,mostly andwork live Serbians now 1,000 thataround andsomeSerbianmedia suggest by manyexpats offered Unofficial numbers +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 Belgrade in Concern Sparks Boom Estate Real Page 7 Issue No. No. Issue [email protected] 260 Friday, October 12 - Thursday, October 25,2018 October 12-Thursday, October Friday, Photo: Pixabay/shanghaibowen Photo: Skilled, adventurous young Serbians young adventurous Skilled, China – lured by the attractive wages wages attractive the by –lured China enough money for a decent life? She She life? adecent for money enough earning of incapable she was herself: adds. she reality,” of colour the got BIRN. told Education, Physical and Sports of ulty Fac Belgrade’s a MAfrom holds who Sparovic, didn’t,” they –but world real the change glasses would rose-tinted my thought and inlove Ifell then But out. tryit to abroad going Serbia and emigrate. to plan her about forget her made almost things These two liked. A Ivana Ivana Sparovic soon started questioning questioning soonstarted Sparovic glasses the –but remained “The love leaving about thought long “I had PROMISED LAND PROMISED SERBIANS HEAD HEAD SERBIANS NIKOLIC are increasingly going to work in in towork going increasingly are place apretty just than more Ljubljana: Page 10 offered in Asia’s economic giant. economic Asia’s in offered DISILLUSIONED love and had a job she ajobshe had and love in madly was She thing. every had she vinced con was Ana Sparovic 26-year-old point, t one FOR CHINA’S CHINA’S FOR - - - BELGRADE INSIGHT IS PUBLISHED BY INSIGHTISPUBLISHED BELGRADE for China. -

Belgrade Rocks - New York Times

Belgrade Rocks - New York Times http://travel.nytimes.com/2005/10/16/travel/16belgrade.html?ei=5070... October 16, 2005 Belgrade Rocks By SETH SHERWOOD Correction Appended NIGHT falls in the capital of the former Yugoslavia, and music fills the air. Everywhere. Along the banks of the Danube and Sava Rivers, serpentine chains of music-blasting splavovi - floating raft clubs - snake into the inky Balkan night. Fortified by huge meat-kebab dinners and Turkish coffees from Belgrade's myriad cafes, crowds of night owls line up to partake variously of Gypsy bands, electronic mixes, rock 'n' roll and a distinctly Serbian hybrid known as Turbofolk. As a parade of Puma-clad feet files down the metal gangway to a club called Exile, the night's marquee D.J., the New York City-based techno producer John Selway, prepares for his 2-to-6 a.m. set. "The most fun places to play are here, South America and Japan!" he shouts over rapid-fire industrial beats, praising the energy of the night life in the capital of Serbia and Montenegro, the name for what is left of Yugoslavia after its unraveling in the early 90's. "They're interested in new music and in building a scene!" Across the water, the lighted dome of St. Sava Church and illuminated stone walls of the centuries-old Kalemegdan Fortress hover over the capital's skyline. Just six years ago, during 78 days of NATO bombings intended to quell President Slobodan Milosevic's attacks on ethnic Albanians in the nation's Kosovo province, that same panorama exploded routinely in flame and debris. -

Remembering Wwi in Belgrade

I lives. their lost who those to memorials poignant several has I–Belgrade War endofWorld the since years 100 marks 2018 Day Armistice and Montenegrins were fighting on the on the fighting were Montenegrins and Macedonians Serbs, The army. that to conscripted were thus and Empire Austro-Hungarian the partof were republics. Yugoslav the of people the between unity” and “brotherhood the undermine could memorations com thought was I asit War World ing mark support not did Yugoslavia mer disrepair. into fell survived that Fabian WWI IN BELGRADE BELGRADE IN WWI REMEMBERING The Croats, Bosnians and Slovenes Slovenes Bosniansand Croats, The for the of government socialist The by German occupiers and those those and German occupiers by II War World during damaged were I.A lot War World rating commemo monuments many are there area Belgrade n the VENDRIG +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 - - - - Dominates’ Dialogue asKosovo Stalls Process ‘Reform Serbia-EU: Pages 2-3 Pages 58 per cent of its adult male population. male adult its of 58 percent and population total then, its, of per cent than26 more Thisrepresented losses. civilian and army both including war, the during inhabitants than 1.1million the Kingdom of Montenegro. of Kingdom the Serbia or of Kingdom the for side other be found in hidden, quiet places. quiet inhidden, be found can and well-known less are most but city inthe locations prominent cupy Serbia in2012. in holiday public anofficial – became 11,1918 November on signed was truce Some World War I monuments oc Imonuments War World Some the when day –the Day Armistice more Serbialost that isestimated It Issue No. -

Conference Abstracts

Belgrade University World Association of Soil and Water Faculty of Forestry Conservation (WASWC) INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON “LAND CONSERVATION” – LANDCON 1209 SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGES September 17-21, 2012 Danube Region/Republic of Serbia Conference Abstracts World Association for International Sediment European Society for Soil Water Management Institute Sedimentation and Erosion Initiative (ISI-UNESCO) Conservation (ESSC) “JAROSLAV ČERNI” Research (WASER) International Conference: Land Conservation – LANDCON 1209 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON „LAND CONSERVATION” – LANDCON 1209 SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGES September 17-21, 2012 Danube Region/Republic of Serbia CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS Editors: Miodrag ZLATIĆ Stanimir KOSTADINOV Belgrade, 2012 1 International Conference on Land Conservation – LANDCON 1209 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON „LAND CONSERVATION” – LANDCON 1209 SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGES September 17-21, 2012 Danube Region/Republic of Serbia Conference Abstracts Publisher: University of Belgrade, Faculty of Forestry Editors: Miodrag ZLATIĆ Stanimir KOSTADINOV Editorial Board: Miodrag ZLATIĆ - University of Belgrade, Faculty of Forestry, Belgrade, Serbia Stanimir KOSTADINOV - University of Belgrade, Faculty of Forestry, Belgrade, Serbia Nada Dragović - University of Belgrade,Faculty of Forestry, Belgrade, Serbia Slobodan PETKOVIĆ - University of Belgrade, Faculty of Forestry, Belgrade, Serbia Editorial Office: Faculty of Forestry Phone: +381 11 3053-990 Kneza Višeslava 1 Fax: -

Serbia's Deals with China Reveal Flawed Business

S Filip transparency. little with and loans, with projects infrastructure – funding investors foreign with practices business its of typical are China in signed have leaders Serbia’s that The agreements build a bypass around Serbia’s capital. Serbia’s around abypass build tember 18. tember Sep on Beijing to visit astate during project, a207-million-euro bypass, the of construction the for agreements two SinisaMalisigned mayor, Belgrade mer projects. ture infrastruc for loans the on rates terest asin aswell factory, bus the into vestor in the to subsidies big uppaying end STRATEGY BUSINESS FLAWED REVEAL CHINA WITH DEALS SERBIA’S Serbian Finance Minister and the for the and Minister Serbian Finance could Serbia fear experts However, RUDIC struct an industrial park and and park anindustrial struct con based manufacturer, bus inaBelgrade- invest panies to Chinese com for deals signed Chinarecently and erbia +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 - - - - - - - for its Future its for Seen asD-Day Referendum Macedonia’s Page 8 dealings with the Asian superpower. Asian the with dealings inSerbia’s common become had practice this that adding job, the do to company aChinese pay Chinato from money ing borrow Serbia ismerely that warns vic tance,” his office said. said. hisoffice tance,” impor strategic isof “Thispass. project by new the to Serbia thanks through go now would goods of transport nancing. fi the for deals the of signing the saw over XiJinping, and Vucic Aleksandar However, economist Milan Kovace economist However, regional most that Mali claimed Chinese Serbianand Presidents, The Issue No. No. Issue [email protected] Continued on on Continued 259 Friday, September 28 - Thursday, October 11,2018 October 28-Thursday, September Friday, page 2 - - - - - - promises of increased economic ties between the two countries. -

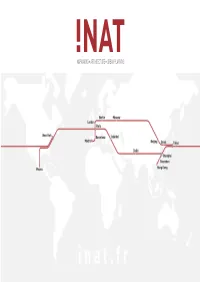

MAPMAKING Ǩ ARCHITECTURE Ǩ URBAN PLANNING ABOUT US Practice and Expertise

MAPMAKING ǩ ARCHITECTURE ǩ URBAN PLANNING ABOUT US Practice and Expertise ABOUT US INAT is an international partnership with transdisciplinary teams based in Paris, Belgrade, Madrid and Hanoi. We provide our clients with innovative solutions adapted to their needs MAPMAKING through our creative research and development approach. Our experience encompasses ǩ,1$7PDSSLQJVWDQGDUG the fields of Mapmaking, Planninig and Urban design. ǩ3DULV ǩ7RN\R ǩ,QIRUPDWLRQV\VWHP Mapmaking Planning Urban design 3/$11,1* Schematic metro network diagrams Planning is a dynamic process of Successful urban environments are an essential tool for travelers discovery. It entails translating a become destinations when designed ǩ Existing network and authorities alike, they help the client's vision into a development to invite an abundance of foot traffic, ǩ Future network former navigate the transport strategy, providing a framework in programmed activities and lively network and the latter plan and which alternatives are evaluated, street scenes – combining develop- URBAN DESIGN implement urban development capacity in determined, feasibility is ment and open spaces to create an ǩ3XEOLFWUDQVSRUW policies. More importantly they are tested and a course is set - all with a exciting, viable neighborhood fabric. instrumental in shaping the identity single goal in mind – creating places Through careful planning and analy- ǩArchitecture and city of the city. These metro maps repre- where people make memories. sis, our urban projects are designed sent not only the structure of the to provide optimal benefits to the CONTACT urban fabric but reflect the paths of surrounding community while milions of people and their design addressing the complexities and and appearence is the most com- intricate relationships that tie our monly shared representation of the cities together. -

5126134 Beno Tmarcou P2 R ... Chplan.Pdf

Research plan Benoît Marcou Research Plan P2 Submitted: 08/01/2021 Benoît Marcou 5126134 MSc3/MSc4 Graduation Studio 20/21: Positions in Practice Towards Inclusive Built Environments in Belgrade, Serbia Chair of Methods of Analysis & Imagination Mentors : Jorge Mejía Hernández Aleksandar Staničić Pierre Jennen Introduction This research and design project focuses on the city of Belgrade and its territories of transit. Historically, its geographic situation has made it a strategic zone during armed conflicts and has also positioned the city as an important stop for migrants and travellers crossing the balkans. In recent years, and especially in 2015, Belgrade appeared to be located in the middle of the so- called ‘Balkan route’ connecting Africa and the Middle East to Western Europe. For many migrants, Belgrade is seen as a space of transit rather than a destination. In addition to these large flows of people, movements of foreign investment have been made visible by recent large scale projects such as Belgrade Waterfront development and the construction of the new “central” station in the Prokop area. These controversial projects, the complexity of Serbian building policies and the extralegal construction culture are touching upon the question of land. The consideration of land as an exclusive territory or as a commodity rather than a common resource requires us to consider the consequences this has in terms of ownership, use and care. According to Bruno Latour in his essay Down to Earth, our “ways of landing” are expressed physically but also philosophically and politically. For him, the act of landing and the development of a sense of belonging have become harder to articulate in an era of intersecting crises and increasing dematerialisation. -

Belgrade at the Confluence of Influences

Srđan Gavrilović Architecture Plus „A+“, Belgrade Serbia BelGrAde At the ConfluenCe of InfluenCeS Resources of Danubian Region: the Possibility of Cooperation and Utilization Editors Luka Č. Popović Melita Vidaković Djordje S. Kostić Belgrade Humboldt-Club Serbien 2013 ISBN 978-86-916771-1-4 SRDJAN GA V R I L O V I ć 132 BEL G RADE AT THE CONFLUENCE OF INFLUENCE S Abstract. The story in which a city begins is most frequently a part of a myth. The myth is the very beginning of everything, the basis of civilisation. How does a city come to be? Where is it conceived? In which civilizational moment of the development of society does it take over the function of the city and how is it different compared to lower rank settlements? Why does it arise on rivers and in vales and why does it last through time? What is determined by and what does it anticipate itself, as the amalgam of things, occurences and influences? At the beginning of the 3rd millenium just like at the beginning of the 20th century Belgrade is dealing with huge urbanistic issues. It came to be as a city on the collision of alluvial planes, on the hill above the position where the river Sava flows into the Danube and it represents the „gates of the Balkans“ as well as the „gates of Central Europe“ with which it is connected via the most significant European waterway. Key words: The City, Architecture, The Danube, Belgrade, Serbia, Fig. 1. „Zmaj’s“ first ilustration, Branko Vasiljević: „Belgrade – 100 years on illustrated postcards“, Belgrade, 1996. -

Serbia CONTINENTAL HOTEL BEOGRAD

Serbia I.H.T. ASTORIA HOTEL, Milovana Milovanica 1, Belgrade, Serbia, Tel. +381 11 264 SERBIA (YUGOSLAVIA) 5422, +381 11 264 5478, Fax: (+381 11) 68 64 37, Email: [email protected], website: www.astoria.co.yu BALKAN HOTEL, Prizrenska 2, Belgrade 11000, Serbia, Tel. +381 11 363 6000, fax. +381 11 268 7581, E-mail: [email protected], website: www.balkanhotel.net BEST WESTERN HOTEL M, Blvd. Oslobodenja 56a, Belgrade 11000, Serbia, Tel. +381 11 309 0401, +381 11 309 0402, Fax. +381 11 309 0403, +381 11 309 5501, E-mail: [email protected], website: www.bestwestern.at BEST WESTERN HOTEL SUMADIJA, Sumadijski trg 8, Belgrade, Serbia, Tel. +381 11 305 4100, +381 11 305 4203, Fax. +381 11 355 4368, E-mail: [email protected], website: www.hotelsumadija.com Country Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++381 VisitSerbia: National Tourism Organization of Serbia, Omladinskih brigade 1, SIV 3, 11070 New Belgrade, Tel. +381 11/ 3342 521, 3232 586, Fax. +381 322 1068, E-mail: [email protected], website: www.serbia-tourism.org Capital: Belgrade Background: Serbs settled the Balkan Peninsula in the 6th and 7th centuries and CONTINENTAL HOTEL BEOGRAD adopted Christianity in the 9th century. In 1166, Stefan Nemanja, a Serbian warrior and th Vladimira Popovica 10, Belgrade 11070, Serbia chief, founded the first Serbian state. By the 14 century, under the rule of Stefan Dusan, it became the most powerful state in the Balkans. After Serbia was defeated in Tel. +381 11 220 4204, Fax. +381 11 311 1402 the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, it was absorbed into the Ottoman Empire. -

Women Feel at Home on Serbia's Far Right

ardent support for Russia, and oppo and Russia, for support ardent politics, nationalist their for all known and denial of rights for gay people. people. gay for rights of denial and abortion to access to limits including – values” family “traditional of promotion parties’ their and equality gender tween S Maja BIRN. told have movements these in active women three clubs, boys-only longer no are parties nationalist hard-line Serbia’s FAR RIGHT FAR SERBIA’S ON HOME AT FEEL WOMEN BIRN spoke with three such women, women, such three with BIRN spoke ZIVANOVIC that there is no conflict be conflict isno there that argue who activists female of acadre promoting image, ist chauvin their shed to trying partiesare far-right erbia’s +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 Risk-Takers Serbia's Grips Fever Bitcoin Page 7 - - - government. the for apriority of bemore should it that arguing rate, birth low Serbia’s over concern express and life”, of “meaning educated. and bemodern to women Serbian want do they say but nism, femi of notions Western temporary bership. mem NATO and EU potential Serbia’s and independence Kosovo’s to sition The say marriage and family are the the are family and marriage say The see ascon they what allreject They Continued on on Continued [email protected] Issue No. No. Issue pages 2 and 3 2and pages 247 Friday, March 9, - Thursday, March 22,2018 March -Thursday, 9, March Friday, - - - Milica Djurdjevic, 27, is a senior member of the far-right nationalist Zavetnici group. Zavetnici nationalist 27,isaseniormemberofthe far-right Djurdjevic, Milica Festival Guitar up Light to Star Portuguese Page 13 BELGRADE INSIGHT IS PUBLISHED BY INSIGHTISPUBLISHED BELGRADE ORDER DELIVERY TO DELIVERY ORDER [email protected] YOUR DOOR YOUR +381 11 4030 303 114030 +381 Friday • June 13 • 2008 NEWS NEWS 1 9 7 7 1 Photo: MedijaCentarPhoto: ISSN 1820-8339 8 2 0 8 3 3 0 0 0 0 1 Issue No. -

Spatium 30.Pdf

SPATIUM International Review ISSN 1450-569X No. 30, December 2013, Belgrade ISSN 2217-8066 (Online) SCOPE AND AIMS The review is concerned with a multi-disciplinary approach to spatial, regional and urban planning and architecture, as well as with various aspects of land use, including housing, environment and related themes and topics. It attempts to contribute to better theoretical understanding of a new spatial development processes and to improve the practice in the field. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PUBLISHER Miodrag Vujošević, IAUS, Belgrade, Serbia Institute of Architecture and Urban & Spatial Planning of Serbia, IAUS VICE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Igor Marić, Director Jasna Petrić, IAUS, Belgrade, Serbia ADDRESS Institute of Architecture and Urban & Spatial Planning of Serbia, IAUS SECRETARY "Spatium" Tamara Maričić, IAUS, Belgrade, Serbia Serbia, 11000 Belgrade, Bulevar kralja Aleksandra 73/II, tel: (381 11) 3370-091, fax: (381 11) 3370-203, e-mail: [email protected], web address: www.iaus.ac.rs IN PUBLISHING SERVICES AGREEMENT WITH Versita Sp. z o.o. ul. Solipska 14A/1 02-482 Warsaw, Poland FINANCIAL SUPPORT Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia “SPATIUM” is indexed in SCOPUS database by Elsevier. EDITORIAL BOARD Branislav Bajat, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Belgrade, Serbia; Milica Bajić Brković, Belgrade, Serbia; Branko Cavrić, University of Botswana, Faculty of Engineering & Technology – FET, Department of Architecture and Planning – DAP, Gaborone, Botswana; Tijana Crnčević, IAUS, Belgrade, Serbia; Kaliopa Dimitrovska Andrews, Ljubljana, Slovenia; Zeynep Enlil, Yildiz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of City and Regional Planning, Istanbul, Turkey; Milorad Filipović; University of Belgrade, Faculty of Economics, Belgrade, Serbia; Panagiotis Getimis, Panteion University of Political and Social Sciences, Dept.