Sarajevo's Holiday Inn on the Frontline of Politics And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STANOVI U NOVOM SADU ZAMENA 1. Centar, 68M2, Menjam Nov Trosoban Stan, Neuseljavan, Za Manji. Tel. 064/130-7321 2. Detelinara No

STANOVI U NOVOM SADU ZAMENA 1. Centar, 68m2, menjam nov trosoban stan, neuseljavan, za manji. Tel. 064/130-7321 2. Detelinara nova, menjam garsonjeru na II spratu, za stan na poslednjem spratu. Tel. 063/730-4699 3. Grbavica, menjam četvorosoban stan 120m2, za dva manja, ili prodajem. Tel. 021/523-147 4. Kej, 61m2, menjam stan, za manji, uz doplatu. Tel. 021/661-4507, 063/766-0101 5. Novo naselje, menjam stan 45m2, visoko prizemlje, za odgovarajući do V sprata sa liftom. Tel. 061/242-9751 6. Novo naselje, menjam stan 76m2, pored škole, za adekvatan stan u okolini Spensa i Keja. Tel. 060/580-0560 7. Petrovaradin, 116m2, menjam stan u kući, 2 nivoa, za 1 ili 2 manja stana, uz doplatu. Tel. 060/718-2038 8. Petrovaradin, menjam nov stan+garaža (71.000€), za stan u Vićenci-Italija. Tel. 069/412-1956 9. Petrovaradin, menjam stan, garaža, 71.000€+džip 18.500€, za trosoban stan. Tel. 063/873-3281 10. Podbara, 35m2, menjam jednoiposoban stan, u izgradnji, za sličan starije gradnje u centru ili okolini Suda. Tel. 062/319-995 11. Sajam, 52m2, menjam dvoiposoban stan, za dvosoban stan na Limanima, Keju. Tel. 064/881-8552 12. Satelit, menjam jednosoban stan, za veći, uz doplatu. Tel. 063/823-2490, 063/822-3724 PRODAJA GARSONJERE 1. Bulevar Evrope, 24m2, nova garsonjera u zgradi, I sprat, na uglu sa Ul.Novaka Radonjića, bez posrednika. Tel. 062/181-6160 2. Cara Dušana, 25m2, uknjižena garsonjera, nameštena, II sprat, lift, cg, klima, balkon, po dogovoru. Tel. 063/893- 0614 3. Detelinara nova, 30m2, garsonjera, uknjižena, renovirana, IV sprat, bez lifta, vlasnik. -

Women Living Islam in Post-War and Post-Socialist Bosnia and Herzegovina Emira Ibrahimpasic

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Anthropology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2012 Women Living Islam in Post-War and Post-Socialist Bosnia and Herzegovina Emira Ibrahimpasic Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Ibrahimpasic, Emira. "Women Living Islam in Post-War and Post-Socialist Bosnia and Herzegovina." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds/35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emira Ibrahimpasic Candidate Anthropology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Carole Nagengast, Ph.D. , Chairperson Louise Lamphere, Ph.D. Melissa Bokovoy, Ph.D. Elissa Helms, Ph.D. i WOMEN LIVING ISLAM IN POST-WAR AND POST-SOCIALIST BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA by EMIRA IBRAHIMPASIC B.A. Hamline University, 2002 M.A. University of New Mexico, 2005 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anthropology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico ii DEDICATION To the memory of my grandparents Nazila (rođ. Ismailović) Salihović 1917-1996 and Mehmed Salihović 1908-1995 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Numerous women and men contributed to this dissertation project. I am grateful for all the guidance, help, and support I received from the women I met over the years. At times, when I felt that many of the questions at hand could not be answered, it was my primary informants that provided contacts and suggestions in how to proceed and address the problems. -

Prosecution's Submission Pursuant to Rule 65

IT-95-5/18-PT 18182 D 18182 - D 15860 18 May 2009 PvK UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No. IT-95-5/18-PT Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 18 May 2009 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Former Yugoslavia since 1991 IN TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Iain Bonomy, Presiding Judge Christoph Flügge Judge Michèle Picard Registrar: Mr. John Hocking THE PROSECUTOR v. RADOVAN KARAD@I] PUBLIC WITH PARTLY CONFIDENTIAL APPENDICES PROSECUTION’S SUBMISSION PURSUANT TO RULE 65 TER (E)(i)-(iii) The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Alan Tieger Ms. Hildegard Uertz-Retzlaff The Accused: Radovan Karad`i} 18181 THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA Case No. IT-95-5/18-PT THE PROSECUTOR v. RADOVAN KARAD@I] PUBLIC WITH PARTLY CONFIDENTIAL APPENDICES PROSECUTION’S SUBMISSION PURSUANT TO RULE 65 TER (E)(i)-(iii) 1. Pursuant to the Trial Chamber’s order of 6 April 20091 and Rule 65 ter (E)(i)- (iii) of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence (“Rules), the Prosecution hereby files: (i) the final version of the Prosecutor's pre-trial brief (Appendix I); (ii) the confidential list of witnesses the Prosecutor intends to call (Appendix II); and (iii) the confidential list of exhibits the Prosecutor intends to offer into evidence (Appendix III). 2. Attached to Appendix I, the final pre-trial brief, are the following: - Confidential Attachment Detailing Events in the Municipalities: these set out the political background and events in the 27 municipalities;2 - Confidential Appendix A: Schedules A-G setting out additional particulars and the supporting evidence for the scheduled incidents; 1 Order Following on Status Conference and Appended Work Plan, 6 April 2009. -

National Reviews 1998 Bosnia and Herzegovina Executive

DANUBE POLLUTION REDUCTION PROGRAMME NATIONAL REVIEWS 1998 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Ministry of Agriculture, Water Management and Forestry in cooperation with the Programme Coordination Unit UNDP/GEF Assistance DANUBE POLLUTION REDUCTION PROGRAMME NATIONAL REVIEWS 1998 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Ministry of Agriculture, Water Management and Forestry in cooperation with the Programme Coordination Unit UNDP/GEF Assistance Preface The National Reviews were designed to produce basic data and information for the elaboration of the Pollution Reduction Programme (PRP), the Transboundary Analysis and the revision of the Strategic Action Plan of the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR). Particular attention was also given to collect data and information for specific purposes concerning the development of the Danube Water Quality Model, the identification and evaluation of hot spots, the analysis of social and economic factors, the preparation of an investment portfolio and the development of financing mechanisms for the implementation of the ICPDR Action Plan. For the elaboration of the National Reviews, a team of national experts was recruited in each of the participating countries for a period of one to four months covering the following positions: Socio-economist with knowledge in population studies, Financial expert (preferably from the Ministry of Finance), Water Quality Data expert/information specialist, Water Engineering expert with knowledge in project development. Each of the experts had to organize his or her work under the supervision of the respective Country Programme Coordinator and with the guidance of a team of International Consultants. The tasks were laid out in specific Terms of Reference. At a Regional Workshop in Budapest from 27 to 29 January 1998, the national teams and the group of international consultants discussed in detail the methodological approach and the content of the National Reviews to assure coherence of results. -

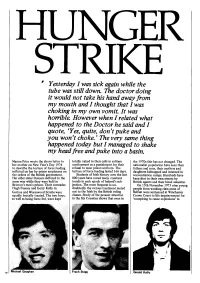

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

SARAJEVO CANTON a PROFITABLE BUSINESS LOCATION Vodic08-EN2.Qxp:Layout 1 4/26/08 9:45 AM Page 2

Bosnia and Herzegovina Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo Canton > A J N A V O L S O P G O N S O N U O T S E J M O V E J A R A S N O T N A K 8 0 0 2 V A J N A G A L U A N O I C I T S E V N I A Z Č I D O INVESTMENTS GUIDE 2008 SARAJEVO CANTON A PROFITABLE BUSINESS LOCATION > o v e j a r a S n o t n a K e n i v o g e c r e H i e n s o B a j i c a r e d e F a n i v o g e c r e H i a n s o B Vodic08-EN2.qxp:Layout 1 4/26/08 9:45 AM Page 1 Bosnia and Herzegovina / Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina SARAJEVO CANTON INVESTMENTS GUIDE 2008 SARAJEVO CANTON A PROFITABLE BUSINESS LOCATION Vodic08-EN2.qxp:Layout 1 4/26/08 9:45 AM Page 2 SARAJEVO CANTON 2008 2 A Profitable Business Location Investments Guide Development Planning Institute of the Sarajevo Canton Director: Said Jamaković, B.Sc. (Arch. ) Project Coordination: Traffic : Socio-Economic Development Planning Sector Almir Hercegovac, B.Sc.C.E. Hamdija Efendić, B.Sc.C.E. Maida Fetahagić M.Sc., Deputy Director Lejla Muhedinović, Technician Ljiljana Misirača, B.Sc.Ec., Head of Department of Development Funds Management and Coordination Geographic Information System: Gordana Memišević, B.Sc.Ec., Head of Department of Jasna Pleho, M.Sc. -

Nijaz Ibrulj Faculty of Philosophy University of Sarajevo BOSNIA PORPHYRIANA an OUTLINE of the DEVELOPMENT of LOGIC in BOSNIA AN

UDK 16 (497.6) Nijaz Ibrulj Faculty of philosophy University of Sarajevo BOSNIA PORPHYRIANA AN OUTLINE OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF LOGIC IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Abstract The text is a drought outlining the development of logic in Bosnia and Herzegovina through several periods of history: period of Ottoman occupation and administration of the Empire, period of Austro-Hungarian occupation and administration of the Monarchy, period of Communist regime and administration of the Socialist Republic and period from the aftermath of the aggression against the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina to this day (the Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina) and administration of the International Community. For each of the aforementioned periods, the text treats the organization of education, the educational paradigm of the model, status of logic as a subject in the educational system of a period, as well as the central figures dealing with the issue of logic (as researchers, lecturers, authors) and the key works written in each of the periods, outlining their main ideas. The work of a Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry, “Introduction” (Greek: Eijsagwgh;v Latin: Isagoge; Arabic: Īsāġūğī) , can be seen, in all periods of education in Bosnia and Herze - govina, as the main text, the principal textbook, as a motivation for logical thinking. That gave me the right to introduce the syntagm Bosnia Porphyriana. SURVEY 109 1. Introduction Man taman ṭaqa tazandaqa. He who practices logic becomes a heretic. 1 It would be impossible to elaborate the development of logic in Bosnia -

Finland in the Olympic Games Medals Won in the Olympics

Finland in the Olympic Games Medals won in the Olympics Medals by winter sport Medals by summer sport Sport Gold Silver Bronz Total e Sport Gol Silv Bron Total Athletics 48 35 31 114 d er ze Wrestling 26 28 29 83 Cross-country skiing 20 24 32 76 Gymnastics 8 5 12 25 Ski jumping 10 8 4 22 Canoeing 5 2 3 10 Speed skating 7 8 9 24 Shooting 4 7 10 21 Nordic combined 4 8 2 14 Rowing 3 1 3 7 Freestyle skiing 1 2 1 4 Boxing 2 1 11 14 Figure skating 1 1 0 2 Sailing 2 2 7 11 Biathlon 0 5 2 7 Archery 1 1 2 4 Weightlifting 1 0 2 3 Ice hockey 0 2 6 8 Modern pentathlon 0 1 4 5 Snowboarding 0 2 1 3 Alpine skiing 0 1 0 1 Swimming 0 1 3 4 Curling 0 1 0 1 Total* 100 84 116 300 Total* 43 62 57 162 Paavo Nurmi • Paavo Johannes Nurmi born in 13th June 1897 • Was a Finnish middle-long-distance runner. • Nurmi set 22 official world records at distance between 1500 metres and 20 kilometres • He won a total of nine gold and three silver medals in his twelve events in the Olympic Games. • 1924 Olympics, Paris Lasse Virén • Lasse Arttu Virén was born in 22th July 1949. • He is a Finnish former long-distance runner • Winner of four gold medals at the 1972 and 1976 Summer Olympics. • München 10 000m Turin Olympics 2006 Ice Hockey • In the winter Olymipcs year 2006 in Turin, the Finnish ice hockey team won Russia 4-0 in the semifinal. -

Micrometeorolgy Study (Low Res Images)

! SELECTION OF REPRESENTATIVE SITES FOR AN URBAN TEMPERATURE MONITORING NETWORK IN NOVI SAD (SERBIA) • Micrometeorology study • Novi Sad, 2013 !! !!! ! Preparation and realization of micrometeorology study: Dufferin Research Ltd. Novi Sad, Serbia Expert: Ana Frank; Albert Ruman Adviser on micrometeorology study preparation and realization: Climatology and Hydrology Research Centre, Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad Novi Sad, Serbia Persons in charge: dr Stevan Savi ć, Dragan Milo ševi ć Micrometeorology study was financed by: IPA HUSRB project Evalutions and public display of URBAN PATterns of Human thermal conditions (acronym: URBAN -PATH) code: HUSRB/1203/122/166 85% was financed by EU 15% was financed by Faculty of Sciences (UNSPMF) ! "! ! !! !!! ! CONTENT Background of urban heat island phenomenon 4 Introduction 4 Causes of urban heat island 6 Consequences of urban heat island 8 Climate change, Global warming and Urban heat island 9 Strategies of urban heat island mitigation 10 Urban heat island investigation 12 Urban heat island investigation of Novi Sad: A review 14 Methods for defining locations of the u rban meteorological stations network 19 The operation of the urban meteorological stations network 21 Locations of urban meteorological stations in Novi Sad 24 References 53 ! #! ! !! !!! ! BACKGROUND OF URBAN HEAT ISLAND PHENOMENON Introduction In the second half of XX th century urbanization reached significant level and because of this half of world population is under negative influence of urban environment, such as: pollution, noise, stress as a consequence of life style, modified parameters of urban climate, etc. (Unger et al, 2011a). As urban areas develop, artificial objects replace open land and vegetation. -

Disillusioned Serbians Head for China's Promised Land

Serbians now live and work in China, mostly in large cities like Beijing andShanghai(pictured). cities like inlarge inChina,mostly andwork live Serbians now 1,000 thataround andsomeSerbianmedia suggest by manyexpats offered Unofficial numbers +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 Belgrade in Concern Sparks Boom Estate Real Page 7 Issue No. No. Issue [email protected] 260 Friday, October 12 - Thursday, October 25,2018 October 12-Thursday, October Friday, Photo: Pixabay/shanghaibowen Photo: Skilled, adventurous young Serbians young adventurous Skilled, China – lured by the attractive wages wages attractive the by –lured China enough money for a decent life? She She life? adecent for money enough earning of incapable she was herself: adds. she reality,” of colour the got BIRN. told Education, Physical and Sports of ulty Fac Belgrade’s a MAfrom holds who Sparovic, didn’t,” they –but world real the change glasses would rose-tinted my thought and inlove Ifell then But out. tryit to abroad going Serbia and emigrate. to plan her about forget her made almost things These two liked. A Ivana Ivana Sparovic soon started questioning questioning soonstarted Sparovic glasses the –but remained “The love leaving about thought long “I had PROMISED LAND PROMISED SERBIANS HEAD HEAD SERBIANS NIKOLIC are increasingly going to work in in towork going increasingly are place apretty just than more Ljubljana: Page 10 offered in Asia’s economic giant. economic Asia’s in offered DISILLUSIONED love and had a job she ajobshe had and love in madly was She thing. every had she vinced con was Ana Sparovic 26-year-old point, t one FOR CHINA’S CHINA’S FOR - - - BELGRADE INSIGHT IS PUBLISHED BY INSIGHTISPUBLISHED BELGRADE for China. -

ITB 2020 4 - 8 March 2020 List of Exhibitors

ITB 2020 4 - 8 March 2020 List of Exhibitors Exhibitor Postal code City Country/Region 1001 Nights Tours 19199 Tehran Iran 123 COMPARE.ME 08006 Barcelona Spain 1AVista Reisen GmbH 50679 Köln Germany 2 Travel 2 Egypt 11391 Cairo Egypt - Prime Hospitality Management Group 33-North Baabdath el Metn Lebanon 360-up Virtual Tour Marketing 40476 Düsseldorf Germany 365 Travel 10000 Hanoi Vietnam 3FullSteps 1060 Nicosia Cyprus 3Sixty Luxury Marketing RG9 2BP Henley on Thames United Kingdom 4Travel Incoming Tour Operator 31-072 Kraków Poland 4X4 Safarirentals GmbH 04229 Leipzig Germany 500 Rai Resort & Tours 84230 Surat Thani Thailand 506 On The River, Woodstock 05091 Woodstock United States of America 5stelle* native clouds pms 43019 Soragna Italy 5vorFlug GmbH 80339 München Germany 7 Degrees South Victoria Seychelles 7/24 Transfer Alanya/Antalya Turkey 7Pines Kempinski Ibiza 07830 Ibiza Spain 9 cities + 2 in Lower Saxony c/o Hannover Marketing & Tourismus GmbH 30165 Hannover Germany A & E Marketing Durbanville, Cape Town South Africa A Dong Villas Company Limited 56380 Hoi An City Vietnam A la Carte Travel Greece 63200 Nea Moudania Greece A Star Mongolia LLC 14250 Ulaanbaatar Mongolia a&o hostels Marketing GmbH 10179 Berlin Germany A-ROSA Flussschiff GmbH 18055 Rostock Germany A-SONO Riga Latvia A. Tsokkos Hotels Public Ltd 5341 Ayia Napa Cyprus A.T.S. Pacific Fiji Nadi Airport Fiji A1 Excursion Adventure Tours and Travel Pvt. Ltd. 44600 Kathmandu Nepal A2 Forum Management GmbH 33378 Rheda-Wiedenbrück Germany A3M Mobile Personal Protection GmbH 72070 Tübingen Germany AA Recreation Tours & Travels Pvt. Ltd. 110058 New Delhi India AAA Hotels & Resorts Pvt Ltd 20040 Male Maldives AAA Travel 7806 Cape Town South Africa AAA-Bahia-Brasil 41810-001 Salvador Brazil AAB - All About Belgium Incoming DMC for the Benelux 9340 Lede Belgium aachen tourist service e.v. -

Accorhotels and Rixos Hotels Announce a Strategic Partnership

Press release - March 6, 2017 AccorHotels and Rixos Hotels announce a strategic partnership AccorHotels and Rixos Hotels announce today a strategic partnership illustrating AccorHotels’ strategy to expand its presence in the Upper Upscale/Luxury market, with a primary focus on developing global activities in the resort segment. Under a long-term joint venture, both parties intend to collaborate, develop and manage Rixos branded resorts & hotels worldwide. Upon closing, AccorHotels will own a 50% interest in the joint venture management company. Through this joint venture, AccorHotels will integrate in its network 15 iconic hotels that are ideally located in premium resort markets in Turkey, UAE, Egypt, Russia and Europe and which benefit from strong room rate performance. As part of this transaction, Rixos plans to reflag five city-centre hotels to AccorHotels brands which will also be managed by AccorHotels. To this portfolio, Rixos will add a second iconic hotel in Dubai in the very short term as well as two other properties by the end of 2018 in Abu Dhabi and the Maldives highlighting the expansion of the Rixos brand into this key resort market. WorldReginfo - fe7ad744-9212-4c3a-9da0-b21390404e8d Rixos is one of only a handful iconic resort brands in the region that caters to both high- end transient and group customers. It is recognized as one of the leading luxury destination brands in Turkey and the Middle East due to its best-in-class facilities, dining options and entertainment venues. Each unique property is able to capture the traditions of its surrounding while providing signature experiences, unforgettable sensory offerings, and unparalleled level of tailored services.