What the Neurocognitive Study of Inner Language Reveals About Our Inner Space Hélène Loevenbruck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Awareness SELF-AWARENESS and SELF-REFLECTION

Na#onal Center for ProfessionalProfessional & R eseaResearchrch & Ethics Ethics Professional Research & Ethics SELF-AWARENESS AND SELF-REFLECTION Of the 147 Delphic Maxims, the most famous is “know thyself.” This maxim is as relevant today as it was in the ancient world. Self-awareness and self-reflection are tools that can help us take charge of our lives and overcome traps of fear, self-deception, or internal monologues that can undermine effectiveness and equilibrium. Explore self-awareness and the importance of reflection, and review thirteen tips for practicing them in your career. Historically, the punishments of banishment Self-Awareness and excommunication emphasize the punitive Sages, writers, philosophers, and theologians nature of being pushed out of a social group. from antiquity forward recommend growing in We are often only partially aware of how much self-awareness. Psychologists recommend self- of our behavior is governed by a desire to be knowledge for a healthy life. Self-awareness, perceived by self and others as “good.” coupled with emotional intelligence about our Our internal monologues are replete with interactions with others, can improve a guiding questions. In addition to the good/bad leader’s effectiveness and comfort in the role. judgment, we ask questions regarding truth (is Internal Monologue something true, false, right, or wrong?), consequences (why? We all have an internal how? because… in monologue: a voice in WE ARE DRIVEN BY AN order to), challenges our heads with which (what is the problem/ we talk to ourselves. We “ INTERNAL MONOLOGUE solution/answer?), use this voice to make duty (I have to/must/ CONSTANTLY ASKING QUESTIONS sense of the world should/can’t/ around us. -

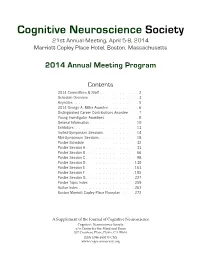

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Talking to Computers in Natural Language

feature Talking to Computers in Natural Language Natural language understanding is as old as computing itself, but recent advances in machine learning and the rising demand of natural-language interfaces make it a promising time to once again tackle the long-standing challenge. By Percy Liang DOI: 10.1145/2659831 s you read this sentence, the words on the page are somehow absorbed into your brain and transformed into concepts, which then enter into a rich network of previously-acquired concepts. This process of language understanding has so far been the sole privilege of humans. But the universality of computation, Aas formalized by Alan Turing in the early 1930s—which states that any computation could be done on a Turing machine—offers a tantalizing possibility that a computer could understand language as well. Later, Turing went on in his seminal 1950 article, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” to propose the now-famous Turing test—a bold and speculative method to evaluate cial intelligence at the time. Daniel Bo- Figure 1). SHRDLU could both answer whether a computer actually under- brow built a system for his Ph.D. thesis questions and execute actions, for ex- stands language (or more broadly, is at MIT to solve algebra word problems ample: “Find a block that is taller than “intelligent”). While this test has led to found in high-school algebra books, the one you are holding and put it into the development of amusing chatbots for example: “If the number of custom- the box.” In this case, SHRDLU would that attempt to fool human judges by ers Tom gets is twice the square of 20% first have to understand that the blue engaging in light-hearted banter, the of the number of advertisements he runs, block is the referent and then perform grand challenge of developing serious and the number of advertisements is 45, the action by moving the small green programs that can truly understand then what is the numbers of customers block out of the way and then lifting the language in useful ways remains wide Tom gets?” [1]. -

Revealing the Language of Thought Brent Silby 1

Revealing the Language of Thought Brent Silby 1 Revealing the Language of Thought An e-book by BRENT SILBY This paper was produced at the Department of Philosophy, University of Canterbury, New Zealand Copyright © Brent Silby 2000 Revealing the Language of Thought Brent Silby 2 Contents Abstract Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: Thinking Sentences 1. Preliminary Thoughts 2. The Language of Thought Hypothesis 3. The Map Alternative 4. Problems with Mentalese Chapter 3: Installing New Technology: Natural Language and the Mind 1. Introduction 2. Language... what's it for? 3. Natural Language as the Language of Thought 4. What can we make of the evidence? Chapter 4: The Last Stand... Don't Replace The Old Code Yet 1. The Fight for Mentalese 2. Pinker's Resistance 3. Pinker's Continued Resistance 4. A Concluding Thought about Thought Chapter 5: A Direction for Future Thought 1. The Review 2. The Conclusion 3. Expanding the mind beyond the confines of the biological brain References / Acknowledgments Revealing the Language of Thought Brent Silby 3 Abstract Language of thought theories fall primarily into two views. The first view sees the language of thought as an innate language known as mentalese, which is hypothesized to operate at a level below conscious awareness while at the same time operating at a higher level than the neural events in the brain. The second view supposes that the language of thought is not innate. Rather, the language of thought is natural language. So, as an English speaker, my language of thought would be English. My goal is to defend the second view. -

Natural Language Processing (NLP) for Requirements Engineering: a Systematic Mapping Study

Natural Language Processing (NLP) for Requirements Engineering: A Systematic Mapping Study Liping Zhao† Department of Computer Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] Waad Alhoshan Department of Computer Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] Alessio Ferrari Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto di Scienza e Tecnologie dell'Informazione "A. Faedo" (CNR-ISTI), Pisa, Italy, [email protected] Keletso J. Letsholo Faculty of Computer Information Science, Higher Colleges of Technology, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, [email protected] Muideen A. Ajagbe Department of Computer Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] Erol-Valeriu Chioasca Exgence Ltd., CORE, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] Riza T. Batista-Navarro Department of Computer Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] † Corresponding author. Context: NLP4RE – Natural language processing (NLP) supported requirements engineering (RE) – is an area of research and development that seeks to apply NLP techniques, tools and resources to a variety of requirements documents or artifacts to support a range of linguistic analysis tasks performed at various RE phases. Such tasks include detecting language issues, identifying key domain concepts and establishing traceability links between requirements. Objective: This article surveys the landscape of NLP4RE research to understand the state of the art and identify open problems. Method: The systematic mapping study approach is used to conduct this survey, which identified 404 relevant primary studies and reviewed them according to five research questions, cutting across five aspects of NLP4RE research, concerning the state of the literature, the state of empirical research, the research focus, the state of the practice, and the NLP technologies used. -

Detecting Politeness in Natural Language by Michael Yeomans, Alejandro Kantor, Dustin Tingley

CONTRIBUTED RESEARCH ARTICLES 489 The politeness Package: Detecting Politeness in Natural Language by Michael Yeomans, Alejandro Kantor, Dustin Tingley Abstract This package provides tools to extract politeness markers in English natural language. It also allows researchers to easily visualize and quantify politeness between groups of documents. This package combines and extends prior research on the linguistic markers of politeness (Brown and Levinson, 1987; Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil et al., 2013; Voigt et al., 2017). We demonstrate two applications for detecting politeness in natural language during consequential social interactions— distributive negotiations, and speed dating. Introduction Politeness is a universal dimension of human communication (Goffman, 1967; Lakoff, 1973; Brown and Levinson, 1987). In practically all settings, a speaker can choose to be more or less polite to their audience, and this can have consequences for the speakers’ social goals. Politeness is encoded in a discrete and rich set of linguistic markers that modify the information content of an utterance. Sometimes politeness is an act of commission (for example, saying “please” and “thank you”) <and sometimes it is an act of omission (for example, declining to be contradictory). Furthermore, the mapping of politeness markers often varies by culture, by context (work vs. family vs. friends), by a speaker’s characteristics (male vs. female), or the goals (buyer vs. seller). Many branches of social science might be interested in how (and when) people express politeness to one another, as one mechanism by which social co-ordination is achieved. The politeness package is designed to make it easier to detect politeness in English natural language, by quantifying relevant characteristics of polite speech, and comparing them to other data about the speaker. -

Natural Language Processing

Natural Language Processing Liz Liddy (lead), Eduard Hovy, Jimmy Lin, John Prager, Dragomir Radev, Lucy Vanderwende, Ralph Weischedel This report is one of five reports that were based on the MINDS workshops, led by Donna Harman (NIST) and sponsored by Heather McCallum-Bayliss of the Disruptive Technology Office of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence's Office of Science and Technology (ODNI/ADDNI/S&T/DTO). To find the rest of the reports, and an executive overview, please see http://www.itl.nist.gov/iaui/894.02/minds.html. Historic Paradigm Shifts or Shift-Enablers A series of discoveries and developments over the past years has resulted in major shifts in the discipline of Natural Language Processing. Some have been more influential than others, but each is recognizable today as having had major impact, although this might not have been seen at the time. Some have been shift-enablers, rather than actual shifts in methods or approaches, but these have caused as major a change in how the discipline accomplishes its work. Very early on in the emergence of the field of NLP, there were demonstrations that NLP could develop operational systems with real levels of linguistic processing, in truly end-to-end (although toy) systems. These included SHRDLU by Winograd (1971) and LUNAR by Woods (1970). Each could accomplish a specific task — manipulating blocks in the blocks world or answering questions about samples from the moon. They were able to accomplish their limited goals because they included all the levels of language processing in their interactions with humans, including morphological, lexical, syntactic, semantic, discourse and pragmatic. -

“Linguistic Analysis” As a Misnomer, Or, Why Linguistics Is in a State of Permanent Crisis

Alexander Kravchenko Russia, Baikal National University of Economics and Law, Irkutsk “Linguistic Analysis” as a Misnomer, or, Why Linguistics is in a State of Permanent Crisis Key words: methodology, written-language bias, biology of language, consensual domain, language function Ключевые слова: методология, письменноязыковая предвзятость, биология языка, консенсуальная область, функция языка Аннотация Показывается ошибочность общепринятого понятия лингвистического анализа как анализа естественного языка. Следствием соссюровского структурализма и фило- софии объективного реализма является взгляд на язык как на вещь (код) – систему знаков, используемых как инструмент для коммуникации, под которой понимается обмен информацией. При таком подходе анализ в традиционной лингвистике пред- ставляет собой анализ вещей – письменных слов, предложений, текстов; все они являются культурными артефактами и не принадлежат сфере естественного языка как видоспецифичного социального поведения, биологическая функция которого состоит в ориентировании себя и других в когнитивной области взаимодействий. До тех пор, пока наукой не будет отвергнута кодовая модель языка, лингвистический анализ будет продолжать обслуживать языковой миф, удерживая лингвистику в со- стоянии перманентного кризиса. 1. Th e problem with linguistics as a science There is a growing feeling of uneasiness in the global community of linguists about the current state of linguistics as a science. Despite a lot of academic activity in the fi eld, and massive research refl ected in the ever growing number of publications related to the study of the various aspects of language, there hasn’t been a major breakthrough in the explorations of language as a unique endowment of humans. 26 Alexander Kravchenko Numerous competing theoretical frameworks and approaches in linguistic re- search continue to obscure the obvious truth that there is very little understanding of language as a phenomenon which sets humans apart from all other known biological species. -

Natural Language Processing and Language Learning

To appear 2012 in Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, edited by Carol A. Chapelle. Wiley Blackwell Natural Language Processing and Language Learning Detmar Meurers Universität Tübingen [email protected] As a relatively young field of research and development started by work on cryptanalysis and machine translation around 50 years ago, Natural Language Processing (NLP) is concerned with the automated processing of human language. It addresses the analysis and generation of written and spoken language, though speech processing is often regarded as a separate subfield. NLP emphasizes processing and applications and as such can be seen as the applied side of Computational Linguistics, the interdisciplinary field of research concerned with for- mal analysis and modeling of language and its applications at the intersection of Linguistics, Computer Science, and Psychology. In terms of the language aspects dealt with in NLP, traditionally lexical, morphological and syntactic aspects of language were at the center of attention, but aspects of meaning, discourse, and the relation to the extra-linguistic context have become increasingly prominent in the last decade. A good introduction and overview of the field is provided in Jurafsky & Martin (2009). This article explores the relevance and uses of NLP in the context of language learning, focusing on written language. As a concise characterization of this emergent subfield, the discussion will focus on motivating the relevance, characterizing the techniques, and delin- eating the uses of NLP; more historical background and discussion can be found in Nerbonne (2003) and Heift & Schulze (2007). One can distinguish two broad uses of NLP in this context: On the one hand, NLP can be used to analyze learner language, i.e., words, sentences, or texts produced by language learners. -

LDL-2014 3Rd Workshop on Linked Data in Linguistics

3rd Workshop on Linked Data in Linguistics: Multilingual Knowledge Resources and Natural Language Processing Workshop Programme 08:30 - 09:00 – Opening and Introduction by Workshop Chair(s) 09:00 – 10:00 – Invited Talk Piek Vossen, The Collaborative Inter-Lingual-Index for harmonizing wordnets 10:00 – 10:30 – Session 1: Modeling Lexical-Semantic Resources with lemon Andon Tchechmedjiev, Gilles Sérasset, Jérôme Goulian and Didier Schwab, Attaching Translations to Proper Lexical Senses in DBnary 10:30 – 11:00 Coffee break 11:00-11:20– Session 1: Modeling Lexical-Semantic Resources with lemon John Philip McCrae, Christiane Fellbaum and Philipp Cimiano, Publishing and Linking WordNet using lemon and RDF 11:20-11:40– Session 1: Modeling Lexical-Semantic Resources with lemon Andrey Kutuzov and Maxim Ionov, Releasing genre keywords of Russian movie descriptions as Linguistic Linked Open Data: an experience report 11:40-12:00– Session 2: Metadata Matej Durco and Menzo Windhouwer, From CLARIN Component Metadata to Linked Open Data 12:00-12:20– Session 2: Metadata Gary Lefman, David Lewis and Felix Sasaki, A Brief Survey of Multimedia Annotation Localisation on the Web of Linked Data 12:20-12:50– Session 2: Metadata Daniel Jettka, Karim Kuropka, Cristina Vertan and Heike Zinsmeister, Towards a Linked Open Data Representation of a Grammar Terms Index 12:50-13:00 – Poster slam – Data Challenge 13:00 – 14:00 Lunch break 14:00 – 15:00 – Invited Talk Gerard de Mello, From Linked Data to Tightly Integrated Data 15:00 – 15:30 – Section 3: Crosslinguistic -

Mechanisms Underlying Auditory Hallucinations— Understanding Perception Without Stimulus

Brain Sci. 2013, 3, 642-669; doi:10.3390/brainsci3020642 OPEN ACCESS brain sciences ISSN 2076-3425 www.mdpi.com/journal/brainsci/ Review Mechanisms Underlying Auditory Hallucinations— Understanding Perception without Stimulus Derek K. Tracy1,2,* and Sukhwinder S. Shergill 1,3 1 Cognition, Schizophrenia & Imaging Laboratory, Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, London SE5 8AF, UK 2 Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust, Princess Royal University Hospital, Kent BR6 8NY, UK 3 National Psychosis Unit, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, Bethlem Royal Hospital, Kent BR3 3BX, UK * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-20-8466-2500; Fax: +44-20-8466-2501. Received: 21 March 2013; in revised form: 7 April 2013 / Accepted: 18 April 2013 / Published: 26 April 2013 Abstract: Auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) are a common phenomenon, occurring in the “healthy” population as well as in several mental illnesses, most notably schizophrenia. Current thinking supports a spectrum conceptualisation of AVH: several neurocognitive hypotheses of AVH have been proposed, including the “feed-forward” model of failure to provide appropriate information to somatosensory cortices so that stimuli appear unbidden, and an “aberrant memory model” implicating deficient memory processes. Neuroimaging and connectivity studies are in broad agreement with these with a general dysconnectivity between frontotemporal regions involved in language, memory and salience properties. Disappointingly many AVH remain resistant to standard treatments and persist for many years. There is a need to develop novel therapies to augment existing pharmacological and psychological therapies: transcranial magnetic stimulation has emerged as a potential treatment, though more recent clinical data has been less encouraging. -

A Joint Model of Language and Perception for Grounded Attribute Learning

A Joint Model of Language and Perception for Grounded Attribute Learning Cynthia Matuszek [email protected] Nicholas FitzGerald [email protected] Luke Zettlemoyer [email protected] Liefeng Bo [email protected] Dieter Fox [email protected] Computer Science and Engineering, Box 352350, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-2350 Abstract ical workspace that contains a number of objects that As robots become more ubiquitous and ca- vary in shape and color. We assume that a robot can pable, it becomes ever more important for understand sentences like this if it can solve the as- untrained users to easily interact with them. sociated grounded object selection task. Specifically, it Recently, this has led to study of the lan- must realize that words such as \yellow" and \blocks" guage grounding problem, where the goal refer to object attributes, and ground the meaning of is to extract representations of the mean- such words by mapping them to a perceptual system ings of natural language tied to the physi- that will enable it to identify the specific physical ob- cal world. We present an approach for joint jects referred to. To do so robustly, even in cases where learning of language and perception models words or attributes are new, our robot must learn (1) for grounded attribute induction. The per- visual classifiers that identify the appropriate object ception model includes classifiers for phys- properties, (2) representations of the meaning of indi- ical characteristics and a language model vidual words that incorporate these classifiers, and (3) based on a probabilistic categorial grammar a model of compositional semantics used to analyze that enables the construction of composi- complete sentences.