“Linguistic Analysis” As a Misnomer, Or, Why Linguistics Is in a State of Permanent Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discussion Notes for Aristotle's Politics

Sean Hannan Classics of Social & Political Thought I Autumn 2014 Discussion Notes for Aristotle’s Politics BOOK I 1. Introducing Aristotle a. Aristotle was born around 384 BCE (in Stagira, far north of Athens but still a ‘Greek’ city) and died around 322 BCE, so he lived into his early sixties. b. That means he was born about fifteen years after the trial and execution of Socrates. He would have been approximately 45 years younger than Plato, under whom he was eventually sent to study at the Academy in Athens. c. Aristotle stayed at the Academy for twenty years, eventually becoming a teacher there himself. When Plato died in 347 BCE, though, the leadership of the school passed on not to Aristotle, but to Plato’s nephew Speusippus. (As in the Republic, the stubborn reality of Plato’s family connections loomed large.) d. After living in Asia Minor from 347-343 BCE, Aristotle was invited by King Philip of Macedon to serve as the tutor for Philip’s son Alexander (yes, the Great). Aristotle taught Alexander for eight years, then returned to Athens in 335 BCE. There he founded his own school, the Lyceum. i. Aside: We should remember that these schools had substantial afterlives, not simply as ideas in texts, but as living sites of intellectual energy and exchange. The Academy lasted from 387 BCE until 83 BCE, then was re-founded as a ‘Neo-Platonic’ school in 410 CE. It was finally closed by Justinian in 529 CE. (Platonic philosophy was still being taught at Athens from 83 BCE through 410 CE, though it was not disseminated through a formalized Academy.) The Lyceum lasted from 334 BCE until 86 BCE, when it was abandoned as the Romans sacked Athens. -

What the Neurocognitive Study of Inner Language Reveals About Our Inner Space Hélène Loevenbruck

What the neurocognitive study of inner language reveals about our inner space Hélène Loevenbruck To cite this version: Hélène Loevenbruck. What the neurocognitive study of inner language reveals about our inner space. Epistémocritique, épistémocritique : littérature et savoirs, 2018, Langage intérieur - Espaces intérieurs / Inner Speech - Inner Space, 18. hal-02039667 HAL Id: hal-02039667 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02039667 Submitted on 20 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Preliminary version produced by the author. In Lœvenbruck H. (2008). Épistémocritique, n° 18 : Langage intérieur - Espaces intérieurs / Inner Speech - Inner Space, Stéphanie Smadja, Pierre-Louis Patoine (eds.) [http://epistemocritique.org/what-the-neurocognitive- study-of-inner-language-reveals-about-our-inner-space/] - hal-02039667 What the neurocognitive study of inner language reveals about our inner space Hélène Lœvenbruck Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, Laboratoire de Psychologie et NeuroCognition (LPNC), UMR 5105, 38000, Grenoble France Abstract Our inner space is furnished, and sometimes even stuffed, with verbal material. The nature of inner language has long been under the careful scrutiny of scholars, philosophers and writers, through the practice of introspection. The use of recent experimental methods in the field of cognitive neuroscience provides a new window of insight into the format, properties, qualities and mechanisms of inner language. -

A Pragmatic Stylistic Framework for Text Analysis

International Journal of Education ISSN 1948-5476 2015, Vol. 7, No. 1 A Pragmatic Stylistic Framework for Text Analysis Ibrahim Abushihab1,* 1English Department, Alzaytoonah University of Jordan, Jordan *Correspondence: English Department, Alzaytoonah University of Jordan, Jordan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 16, 2014 Accepted: January 16, 2015 Published: January 27, 2015 doi:10.5296/ije.v7i1.7015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5296/ije.v7i1.7015 Abstract The paper focuses on the identification and analysis of a short story according to the principles of pragmatic stylistics and discourse analysis. The focus on text analysis and pragmatic stylistics is essential to text studies, comprehension of the message of a text and conveying the intention of the producer of the text. The paper also presents a set of standards of textuality and criteria from pragmatic stylistics to text analysis. Analyzing a text according to principles of pragmatic stylistics means approaching the text’s meaning and the intention of the producer. Keywords: Discourse analysis, Pragmatic stylistics Textuality, Fictional story and Stylistics 110 www.macrothink.org/ije International Journal of Education ISSN 1948-5476 2015, Vol. 7, No. 1 1. Introduction Discourse Analysis is concerned with the study of the relation between language and its use in context. Harris (1952) was interested in studying the text and its social situation. His paper “Discourse Analysis” was a far cry from the discourse analysis we are studying nowadays. The need for analyzing a text with more comprehensive understanding has given the focus on the emergence of pragmatics. Pragmatics focuses on the communicative use of language conceived as intentional human action. -

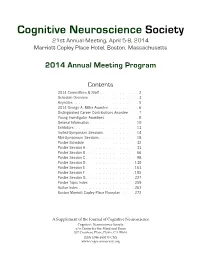

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Mathematics: Analysis and Approaches First Assessments for SL and HL—2021

International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Subject Brief Mathematics: analysis and approaches First assessments for SL and HL—2021 The Diploma Programme (DP) is a rigorous pre-university course of study designed for students in the 16 to 19 age range. It is a broad-based two-year course that aims to encourage students to be knowledgeable and inquiring, but also caring and compassionate. There is a strong emphasis on encouraging students to develop intercultural understanding, open-mindedness, and the attitudes necessary for them LOMA PROGRA IP MM to respect and evaluate a range of points of view. B D E I DIES IN LANGUA STU GE ND LITERATURE The course is presented as six academic areas enclosing a central core. Students study A A IN E E N D N DG two modern languages (or a modern language and a classical language), a humanities G E D IV A O L E I W X S ID U IT O T O G E U or social science subject, an experimental science, mathematics and one of the creative IS N N C N K ES TO T I A U CH E D E A A A L F C T L Q O H E S O R I I C P N D arts. Instead of an arts subject, students can choose two subjects from another area. P G E A Y S A E R S It is this comprehensive range of subjects that makes the Diploma Programme a O S E A Y H T demanding course of study designed to prepare students effectively for university entrance. -

Scientific Discovery in the Era of Big Data: More Than the Scientific Method

Scientific Discovery in the Era of Big Data: More than the Scientific Method A RENCI WHITE PAPER Vol. 3, No. 6, November 2015 Scientific Discovery in the Era of Big Data: More than the Scientific Method Authors Charles P. Schmitt, Director of Informatics and Chief Technical Officer Steven Cox, Cyberinfrastructure Engagement Lead Karamarie Fecho, Medical and Scientific Writer Ray Idaszak, Director of Collaborative Environments Howard Lander, Senior Research Software Developer Arcot Rajasekar, Chief Domain Scientist for Data Grid Technologies Sidharth Thakur, Senior Research Data Software Developer Renaissance Computing Institute University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Chapel Hill, NC, USA 919-445-9640 RENCI White Paper Series, Vol. 3, No. 6 1 AT A GLANCE • Scientific discovery has long been guided by the scientific method, which is considered to be the “gold standard” in science. • The era of “big data” is increasingly driving the adoption of approaches to scientific discovery that either do not conform to or radically differ from the scientific method. Examples include the exploratory analysis of unstructured data sets, data mining, computer modeling, interactive simulation and virtual reality, scientific workflows, and widespread digital dissemination and adjudication of findings through means that are not restricted to traditional scientific publication and presentation. • While the scientific method remains an important approach to knowledge discovery in science, a holistic approach that encompasses new data-driven approaches is needed, and this will necessitate greater attention to the development of methods and infrastructure to integrate approaches. • New approaches to knowledge discovery will bring new challenges, however, including the risk of data deluge, loss of historical information, propagation of “false” knowledge, reliance on automation and analysis over inquiry and inference, and outdated scientific training models. -

Talking to Computers in Natural Language

feature Talking to Computers in Natural Language Natural language understanding is as old as computing itself, but recent advances in machine learning and the rising demand of natural-language interfaces make it a promising time to once again tackle the long-standing challenge. By Percy Liang DOI: 10.1145/2659831 s you read this sentence, the words on the page are somehow absorbed into your brain and transformed into concepts, which then enter into a rich network of previously-acquired concepts. This process of language understanding has so far been the sole privilege of humans. But the universality of computation, Aas formalized by Alan Turing in the early 1930s—which states that any computation could be done on a Turing machine—offers a tantalizing possibility that a computer could understand language as well. Later, Turing went on in his seminal 1950 article, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” to propose the now-famous Turing test—a bold and speculative method to evaluate cial intelligence at the time. Daniel Bo- Figure 1). SHRDLU could both answer whether a computer actually under- brow built a system for his Ph.D. thesis questions and execute actions, for ex- stands language (or more broadly, is at MIT to solve algebra word problems ample: “Find a block that is taller than “intelligent”). While this test has led to found in high-school algebra books, the one you are holding and put it into the development of amusing chatbots for example: “If the number of custom- the box.” In this case, SHRDLU would that attempt to fool human judges by ers Tom gets is twice the square of 20% first have to understand that the blue engaging in light-hearted banter, the of the number of advertisements he runs, block is the referent and then perform grand challenge of developing serious and the number of advertisements is 45, the action by moving the small green programs that can truly understand then what is the numbers of customers block out of the way and then lifting the language in useful ways remains wide Tom gets?” [1]. -

Revealing the Language of Thought Brent Silby 1

Revealing the Language of Thought Brent Silby 1 Revealing the Language of Thought An e-book by BRENT SILBY This paper was produced at the Department of Philosophy, University of Canterbury, New Zealand Copyright © Brent Silby 2000 Revealing the Language of Thought Brent Silby 2 Contents Abstract Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: Thinking Sentences 1. Preliminary Thoughts 2. The Language of Thought Hypothesis 3. The Map Alternative 4. Problems with Mentalese Chapter 3: Installing New Technology: Natural Language and the Mind 1. Introduction 2. Language... what's it for? 3. Natural Language as the Language of Thought 4. What can we make of the evidence? Chapter 4: The Last Stand... Don't Replace The Old Code Yet 1. The Fight for Mentalese 2. Pinker's Resistance 3. Pinker's Continued Resistance 4. A Concluding Thought about Thought Chapter 5: A Direction for Future Thought 1. The Review 2. The Conclusion 3. Expanding the mind beyond the confines of the biological brain References / Acknowledgments Revealing the Language of Thought Brent Silby 3 Abstract Language of thought theories fall primarily into two views. The first view sees the language of thought as an innate language known as mentalese, which is hypothesized to operate at a level below conscious awareness while at the same time operating at a higher level than the neural events in the brain. The second view supposes that the language of thought is not innate. Rather, the language of thought is natural language. So, as an English speaker, my language of thought would be English. My goal is to defend the second view. -

Aristotle's Prime Matter: an Analysis of Hugh R. King's Revisionist

Abstract: Aristotle’s Prime Matter: An Analysis of Hugh R. King’s Revisionist Approach Aristotle is vague, at best, regarding the subject of prime matter. This has led to much discussion regarding its nature in his thought. In his article, “Aristotle without Prima Materia,” Hugh R. King refutes the traditional characterization of Aristotelian prime matter on the grounds that Aristotle’s first interpreters in the centuries after his death read into his doctrines through their own neo-Platonic leanings. They sought to reconcile Plato’s theory of Forms—those detached universal versions of form—with Aristotle’s notion of form. This pursuit led them to misinterpret Aristotle’s prime matter, making it merely capable of a kind of participation in its own actualization (i.e., its form). I agree with King here, but I find his redefinition of prime matter hasty. He falls into the same trap as the traditional interpreters in making any matter first. Aristotle is clear that actualization (form) is always prior to potentiality (matter). Hence, while King’s assertion that the four elements are Aristotle’s prime matter is compelling, it misses the mark. Aristotle’s prime matter is, in fact, found within the elemental forces. I argue for an approach to prime matter that eschews a dichotomous understanding of form’s place in the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato. In other words, it is not necessary to reject the Platonic aspects of Aristotle’s philosophy in order to rebut the traditional conception of Aristotelian prime matter. “Aristotle’s Prime Matter” - 1 Aristotle’s Prime Matter: An Analysis of Hugh R. -

Natural Language Processing (NLP) for Requirements Engineering: a Systematic Mapping Study

Natural Language Processing (NLP) for Requirements Engineering: A Systematic Mapping Study Liping Zhao† Department of Computer Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] Waad Alhoshan Department of Computer Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] Alessio Ferrari Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto di Scienza e Tecnologie dell'Informazione "A. Faedo" (CNR-ISTI), Pisa, Italy, [email protected] Keletso J. Letsholo Faculty of Computer Information Science, Higher Colleges of Technology, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, [email protected] Muideen A. Ajagbe Department of Computer Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] Erol-Valeriu Chioasca Exgence Ltd., CORE, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] Riza T. Batista-Navarro Department of Computer Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, [email protected] † Corresponding author. Context: NLP4RE – Natural language processing (NLP) supported requirements engineering (RE) – is an area of research and development that seeks to apply NLP techniques, tools and resources to a variety of requirements documents or artifacts to support a range of linguistic analysis tasks performed at various RE phases. Such tasks include detecting language issues, identifying key domain concepts and establishing traceability links between requirements. Objective: This article surveys the landscape of NLP4RE research to understand the state of the art and identify open problems. Method: The systematic mapping study approach is used to conduct this survey, which identified 404 relevant primary studies and reviewed them according to five research questions, cutting across five aspects of NLP4RE research, concerning the state of the literature, the state of empirical research, the research focus, the state of the practice, and the NLP technologies used. -

Detecting Politeness in Natural Language by Michael Yeomans, Alejandro Kantor, Dustin Tingley

CONTRIBUTED RESEARCH ARTICLES 489 The politeness Package: Detecting Politeness in Natural Language by Michael Yeomans, Alejandro Kantor, Dustin Tingley Abstract This package provides tools to extract politeness markers in English natural language. It also allows researchers to easily visualize and quantify politeness between groups of documents. This package combines and extends prior research on the linguistic markers of politeness (Brown and Levinson, 1987; Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil et al., 2013; Voigt et al., 2017). We demonstrate two applications for detecting politeness in natural language during consequential social interactions— distributive negotiations, and speed dating. Introduction Politeness is a universal dimension of human communication (Goffman, 1967; Lakoff, 1973; Brown and Levinson, 1987). In practically all settings, a speaker can choose to be more or less polite to their audience, and this can have consequences for the speakers’ social goals. Politeness is encoded in a discrete and rich set of linguistic markers that modify the information content of an utterance. Sometimes politeness is an act of commission (for example, saying “please” and “thank you”) <and sometimes it is an act of omission (for example, declining to be contradictory). Furthermore, the mapping of politeness markers often varies by culture, by context (work vs. family vs. friends), by a speaker’s characteristics (male vs. female), or the goals (buyer vs. seller). Many branches of social science might be interested in how (and when) people express politeness to one another, as one mechanism by which social co-ordination is achieved. The politeness package is designed to make it easier to detect politeness in English natural language, by quantifying relevant characteristics of polite speech, and comparing them to other data about the speaker. -

LING 211 – Introduction to Linguistic Analysis

LING 211 – Introduction to Linguistic Analysis Section 01: TTh 1:40–3:00 PM, Eliot 103 Section 02: TTh 3:10–4:30 PM, Eliot 103 Course Syllabus Fall 2019 Sameer ud Dowla Khan Matt Pearson pronoun: he or they he office: Eliot 101C Vollum 313 email: [email protected] [email protected] phone: ext. 4018 (503-517-4018) ext. 7618 (503-517-7618) office hours: Wed, 11:00–1:00 Mon, 2:30–4:00 Fri, 1:00–2:00 Tue, 10:00–11:30 (or by appointment) (or by appointment) PREREQUISITES There are no prerequisites for this course, other than an interest in language. Some familiarity with tradi- tional grammar terms such as noun, verb, preposition, syllable, consonant, vowel, phrase, clause, sentence, etc., would be useful, but is by no means required. CONTENT AND FOCUS OF THE COURSE This course is an introduction to the scientific study of human language. Starting from basic questions such as “What is language?” and “What do we know when we know a language?”, we investigate the human language faculty through the hands-on analysis of naturalistic data from a variety of languages spoken around the world. We adopt a broadly cognitive viewpoint throughout, investigating language as a system of knowledge within the mind of the language user (a mental grammar), which can be studied empirically and represented using formal models. To make this task simpler, we will generally treat languages as though they were static systems. For example, we will assume that it is possible to describe a language structure synchronically (i.e., as it exists at a specific point in history), ignoring the fact that languages constantly change over time.