Dealing with Urban Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MK241104 Folien

Zürich ist gerüstet für die Bahn 2000. 1 Referenten. Hansjörg Hess Leiter Infrastruktur Mitglied der GL SBB AG Walter Bützer Projekt Management Leiter Knoten Zürich Walter Bürgin Leiter Betriebsführung Zürich 2 Countdown Einführung Bahn 2000 1. Etappe. 3 Bahn 2000:DieInvestitionen. 6 Mia 1 Mia 2 Mia 3 Mia 4 Mia 5 Mia Infrastruktur: Total5,9MiaCHF Total Mattstetten - Rothrist Zürich-Thalwil Genève-Coppet Neubeschaffung: Total 2MiaCHF Total ICN Rollmaterial: Total2,3MiaCHF IC 2000 IC Bt Umrüstung fürNBS: Total 0,3MiaCHF BR, WRc EW IV,AD,EC, 4 Bahn 2000: Das Rollmaterial. Die Bahn 2000 Fernverkehrsflotte InterCity-Neigezug (ICN) IC 2000 Doppelstock Einheitswagen IV Internationale Züge (Basisflotte) 5 Bahn 2000: Die Infrastruktur. Basel Winterthur Aarau Olten Zürich St.Gallen Solothurn Biel Luzern Neuchâtel Bern Chur Lausanne Brig Bellinzona Sion Genève Lugano Realisierte Projekte Projekte kurz vor Inbetriebnahme 6 Mehr Kapazität für den grössten SBB-Bahnhof. S-Bahnhof Museumstrasse Wipkingen Hardbrücke Altstetten Wiedikon S-Bahnhof Sihlpost 7 Walter Bützer Projekt Management Leiter Knoten Zürich 8 Mehr Kapazität für den grössten SBB-Bahnhof. S-Bahnhof Museumstrasse Wipkingen Hardbrücke Altstetten Wiedikon S-Bahnhof Sihlpost 9 Inselbaustellen inmitten des Bahnbetriebs. 10 Mehr Kapazität für den grössten SBB-Bahnhof. S-Bahnhof Museumstrasse Wipkingen Hardbrücke Altstetten Wiedikon S-Bahnhof Sihlpost 11 Neue Vorbahnhofbrücke. 12 Zürich HB: Gleis 3-9 verlängerte Perrons. 13 Bahn 2000 Projekte in Zürich. S-Bahnhof Museumstrasse Wipkingen Hardbrücke Altstetten Wiedikon S-Bahnhof Sihlpost 14 Leistungssteigerung von Altstetten zum Hauptbahnhhof Zürich HB Altstetten 15 Bahn 2000 Projekte in Zürich. S-Bahnhof Museumstrasse Wipkingen Hardbrücke Altstetten Wiedikon S-Bahnhof Sihlpost 16 Neue Vorbahnhofbrücke. Wipkingen Altstetten Zürich HB 17 Zweite Doppelspur Zürich HB Thalwil. -

Quartierspiegel Enge

KREIS 1 KREIS 2 QUARTIERSPIEGEL 2011 KREIS 3 KREIS 4 KREIS 5 KREIS 6 KREIS 7 KREIS 8 KREIS 9 KREIS 10 KREIS 11 KREIS 12 ENGE IMPRESSUM IMPRESSUM Herausgeberin, Stadt Zürich Redaktion, Präsidialdepartement Administration Statistik Stadt Zürich Napfgasse 6, 8001 Zürich Telefon 044 412 08 00 Fax 044 412 08 40 Internet www.stadt-zuerich.ch/quartierspiegel E-Mail [email protected] Texte Nicola Behrens, Stadtarchiv Zürich Michael Böniger, Statistik Stadt Zürich Judith Riegelnig, Statistik Stadt Zürich Rolf Schenker, Statistik Stadt Zürich Kartografie Marco Sieber, Statistik Stadt Zürich Fotografie Regula Ehrliholzer, dreh gmbh Korrektorat Gabriela Zehnder, Cavigliano Druck Statistik Stadt Zürich © 2011, Statistik Stadt Zürich Für nichtgewerbliche Zwecke sind Vervielfältigung und unentgeltliche Verbreitung, auch auszugsweise, mit Quellenangabe gestattet. Committed to Excellence nach EFQM In der Publikationsreihe «Quartierspiegel» stehen Zürichs Stadtquartiere im Mittelpunkt. Jede Ausgabe porträtiert ein einzelnes Quartier und bietet stati stische Information aus dem umfangreichen Angebot an kleinräumigen Daten von Statistik Stadt Zürich. Ein ausführlicher Textbeitrag skizziert die geschichtliche Entwicklung und weist auf Besonderheiten und wich tige Ereignisse der letzten Jahre hin. QUARTIERSPIEGEL ENGE 119 111 121 115 101 122 123 102 61 63 52 92 51 44 71 72 42 12 34 14 13 11 91 41 31 73 24 82 74 33 81 83 21 23 Die Serie der «Quartierspiegel» umfasst alle Quartiere der Stadt Zürich und damit 34 Publikationen, die in regelmässigen Abständen -

Quartierspiegel Lindenhof

KREIS 1 QUARTIERSPIEGEL 2011 KREIS 2 KREIS 3 KREIS 4 KREIS 5 KREIS 6 KREIS 7 KREIS 8 KREIS 9 KREIS 10 KREIS 11 KREIS 12 LINDENHOF IMPRESSUM IMPRESSUM Herausgeberin, Stadt Zürich Redaktion, Präsidialdepartement Administration Statistik Stadt Zürich Napfgasse 6, 8001 Zürich Telefon 044 412 08 00 Fax 044 412 08 40 Internet www.stadt-zuerich.ch/quartierspiegel E-Mail [email protected] Texte Nicola Behrens, Stadtarchiv Zürich Michael Böniger, Statistik Stadt Zürich Judith Riegelnig, Statistik Stadt Zürich Rolf Schenker, Statistik Stadt Zürich Kartografie Marco Sieber, Statistik Stadt Zürich Fotografie Regula Ehrliholzer, dreh gmbh Korrektorat Gabriela Zehnder, Cavigliano Druck Statistik Stadt Zürich ©2011, Statistik Stadt Zürich Für nichtgewerbliche Zwecke sind Vervielfältigung und unentgeltliche Verbreitung, auch auszugsweise, mit Quellenangabe gestattet. Committed to Excellence nach EFQM In der Publikationsreihe «Quartierspiegel» stehen Zürichs Stadtquartiere im Mittelpunkt. Jede Ausgabe porträtiert ein einzelnes Quartier und bietet stati stische Information aus dem umfangreichen Angebot an kleinräumigen Daten von Statistik Stadt Zürich. Ein ausführlicher Textbeitrag skizziert die geschichtliche Entwicklung und weist auf Besonderheiten und wich tige Ereignisse der letzten Jahre hin. RATHAUS HOCHSCHULEN LINDENHOF KREIS 1 CITY QUARTIERSPIEGEL LINDENHOF 119 111 121 115 101 122 123 102 61 63 52 92 51 44 71 72 42 12 34 14 13 11 91 41 31 73 24 82 74 33 81 83 21 23 Die Serie der «Quartierspiegel» umfasst alle Quartiere der Stadt Zürich und -

Neuer Chef Auf Polizeiposten Kreis 10

Noch 2 «Höngger» bis zur Sommerpause: 8. Juli und 15. Juli, die erste Ausgabe nach den Ferien erscheint am 12. August. MedPrax – für Ihre Gesundheit Donnerstag, 1. Juli 2004 Medizinische Massagen Dynamische Wichtig: Nummer 25, 77. Jahrgang Wirbelsäulentherapie Quartierzeitung Heinrich Matthys Self-Coaching, NLP bitte Inserat Immobilien AG von Zürich-Höngg ROLF GRAF in dieser Ausgabe Winzerstrasse 5, Zürich-Höngg Jürg Brunner, med. Masseur FA lesen, siehe Seite 7. PHARMAZIE UND ERNÄHRUNG, ETH Telefon 01 341 77 30 LIMMATTALSTRASSE 177, ZÜRICH-HÖNGG Am Wasser 159, 8049 Zürich Cris und Rudolf Th. Gloor PP 8049 Zürich www.matthys-immo.ch TELEFON 01 341 22 60 Telefon 01 341 53 33, www.medprax.ch Höngg Aktuell Neuer Chef auf Polizeiposten Kreis 10 Jazz and Roiss II Hans Schweizer, Kreischef 10, Während seiner zweijährigen Tätig- übergibt heute sein Amt an Ar- keit von 2002 bis 2004 als stellvertre- Donnerstag, 1. Juli, 20 Uhr, Res- min Lusser. Nach 38-jähriger tender Kreischef der Kreise 3, 4, 5, 9 taurant Jägerhaus. Finnissage und Amtszeit und sechsjähriger Tä- und 10 lernte der 54-Jährige sein jet- Jam-Session von Ivan Kubias and tigkeit in Höngg geht Schweizer ziges Arbeitsumfeld etwas kennen. friends. aus gesundheitlichen Gründen «Im Gegenteil zu den Kreisen 4 und 5, fühlte ich mich in Höngg immer in den vorzeitigen Ruhestand. Exkursion Glühwürmchen sehr wohl», sagt er. Er sehe sich bereits Lusser freut sich auf die Arbeit Freitag, 2. Juli, 21.30 Uhr, Bushal- jetzt von der Bevölkerung akzeptiert. und will sie in ähnlicher Manier testelle Waidbadstrasse. Der Na- «Mit Hans Schweizer als Vorgänger weiterführen. -

Zurich on Foot a Walk Through the Inner City

Postbrücke Bahnhof- platz 1 Bahnhof- Lagerstrasse platz Bahnhofbrücke Kasernenstrasse Schützengasse Waisenhausstr. Bahnhofquai Gessnerbrücke Militärstrasse Löwenstrasse Beaten- Schweizergasse platz Limmatquai Löwen- platz Mühlesteg Usteristrasse Am Rank 2 Militärbrücke Gessnerallee S e i Bahnhofquai d e e n s Löwenstrasse s g a a r s t Rudolf-Brun- 17 3 s Uraniastrasse s Mühleg. n e Brücke Heiristeg e Horner- L n i Bahnhofstrasse r gasse n e 5 d 6 . s r e t a Zähringer- n s Hirschengraben K Oetenbachgasse f platz h r o o se f Predigergasse tras s d Schanzengraben ls t r 4 r e 16 h a Predigerplatz i s d S Rennweg s e i Bahnhofstrasse e Spitalgasse N e Uraniastrasse ass ag Schipfe Hirschen- un rt platz Fo Brunngasse Linden- Limmatquai hof 7 Pfalzgasse Neumarkt Stüssi- hofstatt Wohllebg. M treh S l- ü 15 n Rindermarkt s 14 t U gasse e n r t g e a Spiegelg. r s e s Z e ä u n St.Peter- Wein- Obere Zäune e hofstatt 9 platz 8 Thermen- gasse Ankengasse Limmatquai Schoffelgasse Bahnhofstrasse Zwingli- Storchengasse g platz - a ag s a s W e Kirchgasse Münsterhof 13 10 Münsterbrücke Parade- platz 11 Poststrasse 12 Zentralhof Stadt- haus Tiefen- höfe Fraumünsterstrasse Kappelergasse Bahnhofstrasse Stadthausquai Aerial photograph, 2015 0 50 100 150 200 250m 1 Alfred Escher Fountain 5 Current city model of Zurich 9 Thermengasse 14 Leuenplätzli A figure symbolising a new beginning A view of the city today and perhaps A highlight of Roman bath culture Open space in the middle of the old in the 19th century how it will be tomorrow town 10 Münsterhof 2 -

Quartierspiegel Enge

KREIS 1 KREIS 2 QUARTIERSPIEGEL 2015 KREIS 3 KREIS 4 KREIS 5 KREIS 6 KREIS 7 KREIS 8 KREIS 9 KREIS 10 KREIS 11 KREIS 12 ENGE IMPRESSUM IMPRESSUM Herausgeberin, Stadt Zürich Redaktion, Präsidialdepartement Administration Statistik Stadt Zürich Napfgasse 6, 8001 Zürich Telefon 044 412 08 00 Fax 044 270 92 18 Internet www.stadt-zuerich.ch/quartierspiegel E-Mail [email protected] Texte Nicola Behrens, Stadtarchiv Zürich Michael Böniger, Statistik Stadt Zürich Nadya Jenal, Statistik Stadt Zürich Judith Riegelnig, Statistik Stadt Zürich Rolf Schenker, Statistik Stadt Zürich Kartografie Reto Wick, Statistik Stadt Zürich Fotografie Titelbild, Bild S. 7 oben, Bilder S. 15, Bild S. 27 oben: Roland Fischer, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-3.0 unportiert Bild S. 7 unten: Bobo11, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-3.0 unportiert Bild S. 27 unten: Micha L. Rieser, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-4.0 international Lektorat/Korrektorat Thomas Schlachter Druck FO-Fotorotar, Egg Lizenz Sämtliche Inhalte dieses Quartierspiegels dürfen verändert und in jeglichem For- mat oder Medium vervielfältigt und weiterverbreitet werden unter Einhaltung der folgenden vier Bedingungen: Angabe der Urheberin (Statistik Stadt Zürich), An- gabe des Namens des Quartierspiegels, Angabe des Ausgabejahrs und der Lizenz (CC-BY-SA-3.0 unportiert oder CC-BY-SA-4.0 international) im Quellennachweis, als Fussnote oder in der Versionsgeschichte (bei Wikis). Bei Bildern gelten abwei- chende Urheberschaften und Lizenzen (siehe oben). Der genaue Wortlaut der Li- zenzen ist den beiden Links zu entnehmen: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.de https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de In der Publikationsreihe «Quartierspiegel» stehen Zürichs Stadtquartiere im Mittelpunkt. -

Alt-Wiedikon 2020 AltWiedikon Ist Eines Von 34 Quar Tieren in Der Stadt Und Eines Von Dreien Im Kreis 3

Quartierspiegel Alt-Wiedikon 2020 AltWiedikon ist eines von 34 Quar tieren in der Stadt und eines von dreien im Kreis 3. Aber wussten Sie 2 auch, dass sich Zürich weiter un terteilen lässt, nämlich in 216 sta tistische Zonen? Dies erlaubt einen noch detaillierteren Blick auf die de 3 mografischen, wirtschaftlichen und 1 baulichen Strukturen der Stadt. Die Quartiere sind je nach Grösse und Bebauung in 3 bis 16 statistische Zonen aufgeteilt. Bei der Namensge bung der statistischen Zonen wurden 4 vor allem wichtige Plätze und Stras sennamen verwendet, um die räum liche Orientierung zu erleichtern. Die Einteilung in statistische Quartiere und Zonen folgt nicht immer den im Alltag gängigen Quartierbezeichnun gen und Abgrenzungen. 5 Statistische Zonen: 1 Höfliweg 2 Goldbrunnenplatz 3 Gotthelfstrasse 4 Manesseplatz 5 Binz 6 Saalsporthalle 6 0 250 m 500 m 750 m 1000 m Das Quartier Alt- In Kürze Wiedikon ist einzig- artig! Was es so 17874 besonders macht, Personen erfahren Sie in diesem Quartier- 169,3ha spiegel sowie – Fläche angereichert mit 10247 vielen weiteren Wohnungen Details – unter: stadt-zuerich.ch/ 34,3% quartierspiegel Ausländer/-innen 28569 Arbeitsplätze 3 Alt-Wiedikon Aus dem einstigen Haufen- Wiedo ableitet, was «der Gottgeweihte» bedeutet. Erstmals urkundlich erwähnt wird dorf Wiedikon entwickelte «Wiedingchova» im Jahr 889, als der Grund- sich im 19. und 20. Jahrhun- eigentümer Perchtelo seinen Besitz in Wiedi- dert einer der bevöl- kon dem wenige Jahrzehnte zuvor gegründe- ten Kloster Fraumünster schenkte. Ende des kerungsreichsten Stadtkrei- 15. Jahrhunderts waren die hohe und die se Zürichs. Alt-Wiedikon ist niedere Gerichtsbarkeit an die Stadt Zürich übergegangen, die die Obervogtei Wiedikon eines seiner drei Quartiere. -

20Th ESR-Meeting Arrival:Layout 1

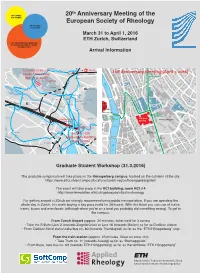

th 18th SWISS 20 Anniversary Meeting of the SOFT DAYS European Society of Rheology FROM MUD TO BLOOD March 31 to April 1, 2016 ETH Zurich, Switzerland 20th ANNIVERSARY MEETING OF THE EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF RHEOLOGY Arrival Information Airport Location Graduate 80 Bahnhof Winterthur ESR Anniversary Meeting (April 1, 2016) Student Workshop Oerlikon Bhf. Oerlikon Schaffhausen Tram 10 from Airport (March 31, 2016) Oerlikon ETH Hönggerberg 11 Bolle L i 10/14 m Sonneg ystrasse 69 m S Chäferberg a p 80 t ö n ZH-Milchbuck gstr d l i Meierhofplatz n asse s t S r . t a m p Buchegg- f 69 Milchbuck e platz n b e a 80 Unter- c A1 rück h Wipkingen strass alche-B s W t Universität Zürichberg ra Weinbergstrasse Zürich-Irchel ss Universitätsstrasse Bhf. e Le ZH-Hardturm/ N Altstetten B o City Schaffhauserplatz Oberstrass a e n h u h Bhf. n m a h r Stern ü d Wipkingen o h s f t - le Bhf. Altstetten MAIN r Au war Q a q asse u s u s tstr f d gstr 9/10 a a e STATION i i asse e . elzber Bhf. Hard- r M enstr Schm Tann brücke Bahnhofstr./HB a 31 Bahnhof-Brück Central u Tram Stop: e e r ETH-Zentrum/ Universitätspital Altstetten Tram 6 & 10 Fluntern ETH Main Zurich Main Station from Main Station Universitätsspital (Hauptbahnhof) Building Beatenplatz tquai Aussersihl 6/5 Seiler Limma asse sse Stra R 10 ETH-Zentrum/ graben id- ä Zä m m istr Universitätspital h Karl Sch 6 Central rin asse g Stauffacher erstr Universität Künstler Albisrieden Bhf. -

Stadt Zürich | Zurich City

Stadt Zürich | Zurich City Zürich Flughafen Tarifzone 110 111 121 Fare zone 110 S9 REGENSDORF 10 S Glattbrugg 762 116 111 1 S24 768 Halden 5 764 12 KATZENSEE 110 Bhf. Lätten- 115 162 Käshaldenstr. Im Ebnet S16 Zentrumwiesen 161 Birch-| 114 113 124 Köschenrüti Glatttalstr. S2 Post 160 118 163 Leimgrübelstr. 123 Schönauring 75 Ausser- 112 120 164 dorfstr. 117 S6 Mühlacker 761 S7 UnteraffolternSchwandenholzWaidhof 742 Ettenfeld 761 Frohbühl- 111 170 62 121 122 171 str. Bhf. Opfikon Chrüzächer Holzerhurd 184 Friedhof Seebach Giebeleichstr. 154 110 130 135 32 Schwandenholz Hertenstein- 131 172 Buhnstr. Lindbergh- OPFIKON 173 Aspholz 40 str. 140 Fronwald platz 155 132 Oberhusen 142 133 Blumen-feldstr. 150 Staudenbühl 141 134 111 Bahnhof 75 143 491 61 Affoltern Nord 768 Lindbergh-Allee 156 151 Hungerbergstr. Maillartstr.Stierenried 180 40 Himmeri Chavez-Allee 152 154 62 Glattpark 182 183 Bhf. Seebach Seebacherplatz Wright-Strasse 153 181 Zehntenhausplatz S6 S21 Fernsehstudio Glaubtenstr.Glaubtenstr. Einfangstr. Hürstholz 12 ENGSTRINGEN 64 Neun- 111 110 Mötteliweg Felsenrain- Grünwald brunnen str. Genossen- 11 Bollinger- schaftsstr. Schauen- berg weg 14 Oerlikerhus Orionstr. Heizenholz Bhf. Auzelg Oerlikon Leutschen- Lerchenhalde Glaubtenstr. Riedbach Rütihof Lerchen- weg Nord bach WALLISELLEN Süd 62 Chalet- 781 rain 79 Herti Belair Giblenstr. Hagenholz Auzelg Ost 46 Schumacherweg Bahnhof 485 80 Geeringstr. Schützenhaus Bhf. Höngg Birchstr. Wallisellen 80 Oerlikon S8 S14 S19 Riedhofstr. Neu- Platz 61 Ost 37 Oberwiesen-Max-Bill- Saatlenstr. S8 Friedhof Bahnhof Hallenbad Riedgraben Dreispitz Aubrücke 89 affoltern str. Hönggerberg Oerlikon 94 Oerlikon 94 Flora- 40 str. 308 Ifang 62 Schürgi- 304 Michelstr. Althoos Frankental ETH 61 str. 110 121 Segantinistr.Singlistr. -

ZÜRICH Schlieren Altstetten Letten Zürichberg

Waldshut Kloten-Nord Buchs Baden Zurich Airport Kloten-Süd Rümlang Kloten Flughafen Glattbrugg Regensdorf Opfikon Dällikon Seebach Schaffhausen Opfikon Bern/Basel Seebach Weiningen Affoltern Affoltern Oerlikon Höngg Altstetten Schwamendingen St.Gallen Winterthur St.Gallen Winterthur Hardturm Unterstrass Urdorf-Nord ZÜRICH Schlieren Altstetten Letten Zürichberg Urdorf Albisrieden Orell Füssli Bahnhof Urdorf-Süd Uitikon Kartographie AG Wiedikon Dietzingerstrasse 3 8003 Zürich Uitikon Witikon Wiedikon Enge Forch Uetliberg Birmensdorf Uto Kulm Brunau Birmensdorf Zollikon Wettswil a.A Wollishofen Wettswil Wollishofen Kilchberg Küsnacht Adliswil Bonstetten Luzern Rüschlikon Thalwil Bahn Erlenbach Railway Hedingen Autobahn Thalwil Motorway Langnau Hauptstrasse Affoltern am Albis Main road am Albis 0 1 2 km Zug/Luzern Zug/Luzern Chur Kartographie ©Orell Füssli AG, Zürich Bern/Basel, ZÜRICH How to find us Winterthur/ Hauptbahnhof Schaffhausen Tram 14 and location Triemli S2, S8, S24 Wiedikon S2 Langstrasse ... by public transport S8 Bahnhofplatz from Zurich central S24 Sihlpost / 14 station (Hauptbahnhof) Hauptbahnhof S Tram 14 from central e Löwenplatz e b station, direction of a h n Triemli to stop s t ra Stauffacher s „Schmiede Wiedikon“. s e Werd Bahnhof Werd Or by S-Bahn from Wiedikon City central station, lines S2, S8, or S24 to S Bahnhof c rmensdor 14 hi „Bahnhof Wiedikon“. Bi fe . m Wiedikon r- r r st t m tr. e rs erds ls A W Schmiede ge e tr in ger . tz e The orell füssli building Wiedikon Di te Z n u s tr. is approximately 200 m rl in d ens and/or 300 m from either tr . of the stops. r t S2 s e s S8 s e n S24 a M Alt- Bahnhof Wiedikon Enge Enge ©Orell Füssli Kartographie ©Orell Füssli AG, Zürich 0 500m Chur .. -

Brunnenguide 174 Zypressen- / Badenerstrasse Lienert Eingeschlagen

197 Meinrad-Lienert-Brunnen 230 Springbrunnen Bullingerplatz 416 Albisrieder Dorfbrunnen 1024 Wasserspiel BRUNNEN KREIS 3 BRUNNEN KREIS 5 Otto Münch gestaltete 1931/32 den Brun- 1929 wurde die Anlage erstellt. Projekt- 1781 wurde der rechteckige Kalkstein- Im Rahmen der Zürcher Herbstmesse 168 Schlossgasse 10/12 1030 Konradstrasse 79 nen aus Segheria-Granit. Die Erzählfigur verfasser war das Zürcher Tiefbauamt. Die Trog mit runder Sandstein-Säule mit Ka- Züspa von 1975 gestaltete der Kantonale 169 Friesenbergstrasse/Zielweg 1132 Langstr.- / Röntgenstrasse ist 1,05 Meter hoch. In der 3,7 Meter Baufirma Fietz & Leuthold wurde mit der pitäl urkundlich erstmals erwähnt. Ein Gärtnermeisterverband vor dem Hallensta- 171 Birmensdorferstrasse/Bremgartenstrasse 1214 Hardturm-Steg/Fischer-Weg hohen Säule sind Sinnsprüche von Meinrad Ausführung betraut. 1985 wurden diverse Kapitäl, heute Kapitell genannt, ist der dion eine Grünanlage. Im Mittelpunkt der 172 Zweierstrasse/Zentralstrasse 1229 Turbinenplatz Brunnenguide 174 Zypressen- / Badenerstrasse Lienert eingeschlagen. Risse ausgefräst, armiert und mit Imitat obere Abschluss einer Säule oder eines Komposition stand das Wasserspiel aus 1240 Hard-/Josefstrasse P geflickt. 2002 erfolgte ein Beleuchtungs- Pfeilers. Auf dem Brunnen ist ein Tatzen- Acrylglasrohren. Dieses wurde von der 176 Uetlibergstrasse bei Nr. 331 1260 Bändlistrasse vor 34 Der Brunnen geht aus einem Brunnenbau- einbau. Früher ans Allgemeine Verteilnetz kreuz angebracht. Dieses Symbol weist Wasserversorgung übernommen und steht 177 Manesseplatz/Uetlibergstrasse 1269 Pfingstweidstrasse vor 85 178 Schwendenweg/Zweierstrasse programm des damaligen Bauwesens II, angeschlossen, wurde der Brunnen 2006 auf die einstige territoriale Zugehörigkeit seit 1978 auf der Nordseite des Dienstge- 245 Johannesgasse/Langstrasse 179 Moosgutstrasse nach 2 heute Hochbaudepartement, aus den Jah- auf Quellwasser umgestellt. -

Zürichsee | Lake Zurich

Waldshut (D) S3S 36 Koblenz S1S 6 19 9 Koblenz Dorf KKlingna lingnau DöttingenDöttin u Rietheim ge Bad Zurzach n Rekingen AG Siggenthal iggenthali WWü g Mellikon renlingee NiederweningenNiederweningderweningweeni geen - Rümikon AG n REGENSDORF Kaiserstuhl AG NiederweniNiNNiederweningenweningenwe DoDorfrf S1S 12 2 S1S ZweidleZwei n NeuhausenNeu Rheinf Schöfflisdorf-sddo 15 Brugg AG 5 h Oberweningen ausen Lottstetten (D) ScS NeuNeuhausenchaffhausenh Steinmaurnm JestettenJestetten (D)(D aff HerHerblingen R ThayngenTh h h h b ayng Turgi S3S einf ause ausenlingen Aarau 36 Baden 6 RafzRa e S4S Dielsdorls rff (D al n 42 Lenzburg f l n 2 Wettingen Würrenlos z ) ENGSTRINGEN S1S Glattfelden Eglisau Eglisau Eglisau Eglisau 11 Otelfingen Hüntwangen- 1 Bülac Othmarsingen S6S Niederhasle lii S9S 111 6 NiederglattNiederN S3S Feuerthalen Neuenhof ie 3 9 154 Mägenwil Otelfingen e S4S el S1S Langwiesen h ScS 12 41 d Golfparlflfpfpf k 1 hloss Laufen2 Mellingen Heitersbertersbergg MaM l Schlatt KillwangenKillwanggen-e - t ar Dac Buucchs- Oberglattlatt rt a S1S SpreitSpreitenbaeitenbace chh hahale ch La St. Katharinental 17 Dällikkoonn Wi hsen 7 l ufen Embracbrach-Rorbas l n Diessenhofen Zürich AAndelfinge Dietikkoonn Regensdorf-Wf Watttt Rümlangng S2 ndelfinge Schlattingen Wo Bremga Bremga Beri Rudolfstetten Bremga Beri Bremga hlen Wo FlughafenFllu afen S1S 16 , hlen Zürich Affolterfol n 6 Stein am Rhein n- ko n n- ko Glanzenbnberg EtzwilenEtzw Pfungen n Regensdorf Regensdorf S1S HenggarH StammStammheimi rt rt rt rt Glattbrugtbbrrrugugu g len Wide Dietikon Schliere Wide Chrüzächer 19 enggar en en en Meuchwis en 9 Geiss- 111 ScS hlierenen S29 mheim R en Zürich Seebach h weid Holzerhurd h We We ei Bahnhof Nord Rütihof 110 KATZENSEE S2S HettlingeHett t 9 OssingenOs n n KKloten Winterthur S2S OpfikO KlotenK Balsberl 24 S4S sss i n Schlieren S6 21 oten 4 41 s st Zentrum/ st Grünwald 1 Wülflingen 1 linge Bahnhof Geeringstr.