Erosion Control at Outer Island Light Station, Revised Environmental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

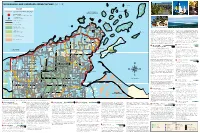

WLSSB Map and Guide

WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY (WLSSB) DEVILS ISLAND NORTH TWIN ISLAND MAP KEY ROCKY ISLAND SOUTH TWIN ISLAND CAT ISLAND WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY APOSTLE ISLANDS BEAR ISLAND NATIONAL LAKESHORE KIOSK LOCATION IRONWOOD ISLAND SCENIC BYWAY NEAR HERBSTER SAILING ON LAKE SUPERIOR LOST CREEK FALLS KIOSKS CONTAIN DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT EACH LOCATION SAND ISLAND VISITOR INFORMATION OUTER ISLAND YORK ISLAND SEE REVERSE FOR COMPLETE LIST µ OTTER ISLAND FEDERAL HIGHWAY MANITOU ISLAND RASPBERRY ISLAND STATE HIGHWAY COUNTY HIGHWAY 7 EAGLE ISLAND NATIONAL PARKS ICE CAVES AT MEYERS BEACH BAYFIELD PENINSULA AND THE APOSTLE ISLANDS FROM MT. ASHWABAY & NATIONAL FOREST LANDS well as a Heritage Museum and a Maritime Museum. Pick up Just across the street is the downtown area with a kayak STATE PARKS K OAK ISLAND STOCKTON ISLAND some fresh or smoked fish from a commercial fishery for a outfitter, restaurants, more lodging and a historic general & STATE FOREST LANDS 6 GULL ISLAND taste of Lake Superior or enjoy local flavors at one of the area store that has a little bit of everything - just like in the “old (!13! RED CLIFF restaurants. If you’re brave, try the whitefish livers – they’re a days,” but with a modern flair. Just off the Byway you can MEYERS BEACH COUNTY PARKS INDIAN RESERVATION local specialty! visit two popular waterfalls: Siskiwit Falls and Lost Creek & COUNTY FOREST LANDS Falls. West of Cornucopia you will find the Lost Creek Bog HERMIT ISLAND Walk the Brownstone Trail along an old railroad grade or CORNUCOPIA State Natural Area. Lost Creek Bog forms an estuary at the take the Gil Larson Nature Trail (part of the Big Ravine Trail MICHIGAN ISLAND mouths of three small creeks (Lost Creek 1, 2, and 3) where System) which starts by a historic apple shed, continues RESERVATION LANDS they empty into Lake Superior at Siskiwit Bay. -

Apostle Islands National Seashore

Apostle Islands National Seashore David Speer & Phillip Larson October 2nd Fieldtrip Report Table of Contents Introduction 1 Stop 1: Apostle Island Boat Cruise 1 Stop 2: Coastal Geomorphology 5 Stop 3: Apostle Islands National Seashore Headquarters 12 Stop 4: Northern Great Lakes Visitors Center 13 Stop 5: Montreal River 16 Stop 6: Conclusion 17 Bibliography 18 Introduction: On October 2nd, 2006, I and the other Geomorphology students took a field excursion to the Apostle Islands and the south shore of Lake Superior. On this trip we made five stops along our journey where we noted various geomorphic features and landscapes of the Lake Superior region. We reached the south coast of Lake Superior in Bayfield, Wisconsin at around 10:00am. Here we made our first stop which included the entire boat trip we took which navigated through the various islands in the Apostle Island National Lakeshore. Our second stop was a beach on the shore of Lake Superior where we noted active anthropogenic and environmental changes to a shoreline. Stop three was at the visitor center for the Apostle Island National Lakeshore where we heard a short talk by the resident park ranger as he explained some of the unique features of the islands and why they should be protected. After that we proceeded to our fourth stop which was at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center. Here we learned, through various displays and videos, how the region had been impacted by various events over time. Finally our fifth stop was at the point where the Montreal River emptied into Lake Superior (Figure 1). -

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements The County Comprehensive Planning Committee Ashland County Staff Gary Mertig Jeff Beirl George Mika Tom Fratt Charles Ortman Larry Hildebrandt Joe Rose Emmer Shields Pete Russo, Chair Cyndi Zach Jerry Teague Natalie Cotter Donna Williamson Brittany Goudos-Weisbecker UW-Extension Ashland County Technical Advisory Committee Tom Wojciechowski Alison Volk, DATCP Amy Tromberg Katy Vosberg, DATCP Jason Fischbach Coreen Fallat, DATCP Rebecca Butterworth Carl Beckman, USDA – FSA Haley Hoffman Gary Haughn, USDA – NRCS Travis Sherlin Nancy Larson, WDNR Stewart Schmidt Tom Waby, BART Funded in part by: Funded in part by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management Under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant #NA15NOS4190094. Cover Page Photo Credit: Ashland County Staff Table of Contents: Background Section Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1-1 Housing ................................................................................................................................................ 2-6 Transportation .................................................................................................................................. 3-24 Utilities & Community Facilities ..................................................................................................... 4-40 Agricultural, Natural & Cultural Resources ................................................................................ -

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2015/972 ON THIS PAGE An opening in an ice-fringed sea cave reveals ice flows on Lake Superior. Photograph by Neil Howk (National Park Service) taken in winter 2008. ON THE COVER Wind and associated wave activity created a window in Devils Island Sandstone at Devils Island. Photograph by Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich (Colorado State University) taken in summer 2010. Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2015/972 Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich Colorado State University Research Associate National Park Service Geologic Resources Division Geologic Resources Inventory PO Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 May 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. -

Fifty Years in the Northwest: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Fifty years in the Northwest L34 3292 1 W. H. C. Folsom FIFTY YEARS IN THE NORTHWEST. WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND APPENDIX CONTAINING REMINISCENCES, INCIDENTS AND NOTES. BY W illiam . H enry . C arman . FOLSOM. EDITED BY E. E. EDWARDS. PUBLISHED BY PIONEER PRESS COMPANY. 1888. G.1694 F606 .F67 TO THE OLD SETTLERS OF WISCONSIN AND MINNESOTA, WHO, AS PIONEERS, AMIDST PRIVATIONS AND TOIL NOT KNOWN TO THOSE OF LATER GENERATION, LAID HERE THE FOUNDATIONS OF TWO GREAT STATES, AND HAVE LIVED TO SEE THE RESULT OF THEIR ARDUOUS LABORS IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE WILDERNESS—DURING FIFTY YEARS—INTO A FRUITFUL COUNTRY, IN THE BUILDING OF GREAT CITIES, IN THE ESTABLISHING OF ARTS AND MANUFACTURES, IN THE CREATION OF COMMERCE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE, THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR, W. H. C. FOLSOM. PREFACE. Fifty years in the Northwest http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.01070 Library of Congress At the age of nineteen years, I landed on the banks of the Upper Mississippi, pitching my tent at Prairie du Chien, then (1836) a military post known as Fort Crawford. I kept memoranda of my various changes, and many of the events transpiring. Subsequently, not, however, with any intention of publishing them in book form until 1876, when, reflecting that fifty years spent amidst the early and first white settlements, and continuing till the period of civilization and prosperity, itemized by an observer and participant in the stirring scenes and incidents depicted, might furnish material for an interesting volume, valuable to those who should come after me, I concluded to gather up the items and compile them in a convenient form. -

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

National Park Service Park News & Planner ‑ 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper of Around the Archipelago Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Pardon the Mess... The Greatest Show on the Big Lake! Closed For Renovation You’d haVE TO GO BACK TO 1929 TO SEE AnytHING LIKE ‑ the 2013 Apostle Islands light station preservation project. Big We know how disappointing a “Closed for happenings at Michigan Island Light: workmen, barges, scaffolding, Renovation” sign can be. We hope that painters, roofers, sawyers, carpenters, glaziers, and masons, all the inconvenience of not climbing the light just busy as beavers. And not just Michigan, but Devils, La Pointe, towers this summer will be rewarded by Outer, and Sand lights too. This is the biggest historic preservation great visitor experiences in the future. project that Apostle Islands National Lakeshore has ever While the National Park Service will work undertaken, and the biggest re-investment in these historic lights to minimize public impacts during the ever made by the federal government. There may NEVER have been light station repair work, some closures a summer this busy at the Apostle Islands’ lighthouses. will be necessary for public safety and to allow workers access to the light stations. Local folks and park visitors have heard rumblings about this for Buildings will be closed to visitation while several years as the planning, design, and contract preparation work work is in progress, as will the adjacent progressed. The lights will be seeing some old friends, and making grounds. The normal volunteer “keepers” some new ones. C3, LLC, a major national construction firm, is the will not be in residence during construction. -

Apostle Islands Sea Kayaking

University of Minnesota Duluth – Recreational Sports Outdoor Program Apostle Islands Sea Kayaking Pick Your Dates HERE’S WHAT TO EXPECT: Explore More with RSOP: The freedom and excitement that Lake Superior sea kayaking offers is •Whitewater Kayak Courses something we’re thrilled to share with you! As a participant you will be actively involved and learning about equipment, paddling techniques, •Whitewater Canoe Courses navigation, on-water safety, and camping from sea kayaks. The itinerary will allow time to explore the natural features and cultural history of the •Rock Climbing on Minnesota’s Apostle Islands. North Shore WHO: •Rock Climbing Wall This trip is suited for all skill levels. Paddlers will be using a combination of single and tandem kayaks. •American Canoe Association Instructor Certification Workshops WHERE: Meet your instructors at the Little Sand Bay Visitor Center, Apostle Islands •Climbing Instructor Certifica- National Lakeshore or Red Cliff Casino. tion and Training Workshops COST: •Summer Youth Adventure $450/person/(2-3 people) Camps $425/person/(4-6 people) General Information and ITINERARY: Registration Phone: (218) 726-7128 As a participant, your abilities and expectations must be appropriate for the Fax: (218) 726-6767 following generalized conditions: Email [email protected] Website www.umdrsop.org 1. Lake Superior’s water temperature is in the fouties this time of year except for the shallow bays where water is warmed by the sun. A farmer Sea Kayaking Information john wetsuit and various poly-nylon layers, and a lifejacket will be worn at Call Pat Kohlin at 218-726-8801 all times. Weather and unforeseen group situations can create the need to alter our on-water activities. -

A. Name of Multiple Property Listing______Great Lakes Shipwrecks of Wisconsin______

NFS FORM 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan 1987) Wisconsin Word Processor Format (MPL.txt) (Approved 10/88) r ^" f f -^ '-- , United States Department of Interior [-...I National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OP HISTORIC PLACES ^1 f - MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM iv^i=V; Vi\M This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a) and identify the section being continued. Type all entries. Use letter quality printer in 12 pitch, using an 85 space line and 10 space left margin. Use only archival quality paper (20 pound, acid free paper with a 2% alkaline reserve). A. Name of Multiple Property Listing__________________________ Great Lakes Shipwrecks of Wisconsin__________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts 1. The Fur Trade, 1634-1850 2. Settlement, 1800-1930 3. The Earlv Industries: Fishing, Lumber, Minincr, and Agriculture, 1800-1930 4. Package Freight, 1800-1930 5. Government, 1830-1940 C. Geographical Data The territorial waters of the State of Wisconsin within Lakes Superior and Michigan, including all port areas in Wisconsin that have accommodated Great Lakes shipping in the past (Figure 1). See continuation sheet D. Certifi cation As designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form meets the requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register Criteria. -

Wisconsin Magazine of History

(ISSN 0043-6534) WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY The State Historical Society oJ Wisconsin • Vol. 79, No. 3 • Spring, 1996 ..}.**. •-.•'••* • c-.<>>i : '>»4i,-..';,-...*fc*i ^%-! fe m^^ \^:- <4'3%>-^ -^^^ •r^ THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN H. NicHOiAS MULLER III, Director Officers GLENN R. C^OATEES, President RICHARD H. HOLSCHER, Treasurer GERALD D. VISTE, First Vice-President H. NiciioiAS MULLER III, Secretary PATRICIA A. B<H;E, Second Vice-Presidenl The State Historical Society of Wisconsin is both a state agency and a private membership organization. Foimded in 1846—two years before statehood—and chartered in 18.53, it is the oldest American historical society to receive continiioirs public funding. By statute, it is charged with collecting, advancing, and disseminating knowledge ofWisconsin and ofthe trans-Allegheny West. The Society serves as the archive ofthe State ofWisconsin; it collects all manner of books, periodicals, maps, manuscripts, relics, newspapers, and aural and graphic materials as they relate to North America; it.maintains a mnseinn, library, and research facility in Madison as well as a statewide system of historic sites, school services, area research centers, and affiliated local societies; it administers a broad program of historic preservation; and publishes a wide variety of historical materials, both scholarly and popular. Membership in the Society is open to the public. Individual membership (one person) is $27..50. Senior Citizen Individualmeinhership is $22.50. FnmiVy membership is $.32.50. .Senior Citizen /•ami/v membership is $27.50. .Supporting-membership is $100. Sustainingmetnherfihip is $250. A Patron contributes $500 or more. /,i/gmembership (one person) is $1,000. -

Michigan Wisconsin Minneso Ta Ont Ario

458 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 13 Chapter 6, Pilot Coast U.S. 88°W 86°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 6—Chapter 13 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage 2312 http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml NIPIGON BAY 92°W 90°W BLACK BAY 2304 State Islands ONTARIO 14968 THUNDER 2303 under Bay BAY 2313 2308 a l e 14976 2309 14967 R o y 48°N I s l e CANADA Grand Marais UNITED ST Michipicoten Island MINNESOTA 14964 ATES Taconite Harbor L AKE SUPERIOR 2307 14972 14966 Hancock 2310 A Y Two Harbors Apostle Islands Houghton B A W N 47°N E E W E Duluth K Ontonagon 14975 Port Wing 14971 14970 Superior 14974 14969 Grand Marais Ashland Marquette WHITEFISH BAY 14965 14963 14884 Munising 14962 WISCONSIN MICHIGAN 46°N 19 SEP2021 19 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 13 ¢ 459 Lake Superior (1) and fall; the lowest stage is usually reached at about the Chart Datum, Lake Superior close of winter and the highest during the late summer. (14) In addition to the normal seasonal fluctuation, (2) Depths and vertical clearances under overhead cables oscillations of irregular amount and duration are also and bridges given in this chapter are referred to Low Water produced by storms. Winds and barometric pressure Datum, which for Lake Superior is an elevation 601.1 feet changes that accompany squalls can produce fluctuations (183.2 meters) above mean water level at Rimouski, QC, that last at the most a few hours. -

To Feed, Fuel, and Build the Heartland: Underwater Archaeological Investigations from the 2014 Field Season

To Feed, Fuel, and Build the Heartland: Underwater Archaeological Investigations from the 2014 Field Season State Archaeology and Maritime Preservation Technical Report Series #15-002 Tamara L. Thomsen and Caitlin N. Zant Assisted by grant funding from the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, and the National Sea Grant College Program, this report was prepared by the Wisconsin Historical Society. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute or the National Sea Grant College Program. Note: At the time of publication, Hanover, Success, and Pathfinder sites are pending listing on the State and National Registers of Historic Places. Amongst the quarry docks surveyed, Bass Island Brownstone Company is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and an amendment to the nomination to include information on the submerged dock ruins has been submitted. Hermit Island Brownstone Quarry and Stockton Island Brownstone Quarry are waiting additional terrestrial work by the National Park Service before a nomination packet can be submitted. Cover photo: Archaeologist Caitlin Zant documents the scow schooner Success in Whitefish Bay, Door County, Wisconsin. Copyright © 2015 by Wisconsin Historical Society All rights reserved CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS AND IMAGE............................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS........................................................................