Apostle Islands National Seashore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

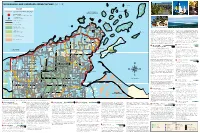

WLSSB Map and Guide

WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY (WLSSB) DEVILS ISLAND NORTH TWIN ISLAND MAP KEY ROCKY ISLAND SOUTH TWIN ISLAND CAT ISLAND WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY APOSTLE ISLANDS BEAR ISLAND NATIONAL LAKESHORE KIOSK LOCATION IRONWOOD ISLAND SCENIC BYWAY NEAR HERBSTER SAILING ON LAKE SUPERIOR LOST CREEK FALLS KIOSKS CONTAIN DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT EACH LOCATION SAND ISLAND VISITOR INFORMATION OUTER ISLAND YORK ISLAND SEE REVERSE FOR COMPLETE LIST µ OTTER ISLAND FEDERAL HIGHWAY MANITOU ISLAND RASPBERRY ISLAND STATE HIGHWAY COUNTY HIGHWAY 7 EAGLE ISLAND NATIONAL PARKS ICE CAVES AT MEYERS BEACH BAYFIELD PENINSULA AND THE APOSTLE ISLANDS FROM MT. ASHWABAY & NATIONAL FOREST LANDS well as a Heritage Museum and a Maritime Museum. Pick up Just across the street is the downtown area with a kayak STATE PARKS K OAK ISLAND STOCKTON ISLAND some fresh or smoked fish from a commercial fishery for a outfitter, restaurants, more lodging and a historic general & STATE FOREST LANDS 6 GULL ISLAND taste of Lake Superior or enjoy local flavors at one of the area store that has a little bit of everything - just like in the “old (!13! RED CLIFF restaurants. If you’re brave, try the whitefish livers – they’re a days,” but with a modern flair. Just off the Byway you can MEYERS BEACH COUNTY PARKS INDIAN RESERVATION local specialty! visit two popular waterfalls: Siskiwit Falls and Lost Creek & COUNTY FOREST LANDS Falls. West of Cornucopia you will find the Lost Creek Bog HERMIT ISLAND Walk the Brownstone Trail along an old railroad grade or CORNUCOPIA State Natural Area. Lost Creek Bog forms an estuary at the take the Gil Larson Nature Trail (part of the Big Ravine Trail MICHIGAN ISLAND mouths of three small creeks (Lost Creek 1, 2, and 3) where System) which starts by a historic apple shed, continues RESERVATION LANDS they empty into Lake Superior at Siskiwit Bay. -

Apostle Islands National Lakehore Geologic Resources Inventory

Geologic Resources Inventory Scoping Summary Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Division Prepared by Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich National Park Service August 7, 2010 US Department of the Interior The Geologic Resources Inventory (GRI) provides each of 270 identified natural area National Park System units with a geologic scoping meeting and summary (this document), a digital geologic map, and a geologic resources inventory report. The purpose of scoping is to identify geologic mapping coverage and needs, distinctive geologic processes and features, resource management issues, and monitoring and research needs. Geologic scoping meetings generate an evaluation of the adequacy of existing geologic maps for resource management, provide an opportunity to discuss park-specific geologic management issues, and if possible include a site visit with local experts. The National Park Service held a GRI scoping meeting for Apostle Islands National Lakeshore on July 20-21, 2010 both out in the field on a boating site visit from Bayfield, Wisconsin, and at the headquarters building for the Great Lakes Network in Ashland, Wisconsin. Jim Chappell (Colorado State University [CSU]) facilitated the discussion of map coverage and Bruce Heise (NPS-GRD) led the discussion regarding geologic processes and features at the park. Dick Ojakangas from the University of Minnesota at Duluth and Laurel Woodruff from the U.S. Geological Survey presented brief geologic overviews of the park and surrounding area. Participants at the meeting included NPS staff from the park and Geologic Resources Division; geologists from the University of Minnesota at Duluth, Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, and U.S. Geological Survey; and cooperators from Colorado State University (see table 2). -

Erosion Control at Outer Island Light Station, Revised Environmental

EROSION CONTROL AT OUTER ISLAND LIGHT STATION REVISED ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Apostle Island National Lakeshore, Wisconsin NPS Contract Number: 1443-CX-2000-99-003 Task Order Number: T20009900328 April 2003 Prepared By: WOOLPERT LLP NATIONAL PARK SERVICE EROSION CONTROL AT OUTER ISLAND LIGHT STATION REVISED ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Prepared By: Woolpert LLP 409 East Monument Avenue Dayton, Ohio 45402 April 2003 Outer Island Environmental Assessment 1 4/03 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 Purpose and Need........................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Background .................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Project Background and Scope ......................................................................... 3 2.2 Relationship to Other Actions and Plans........................................................... 4 2.3 Issues................................................................................................................. 4 2.4 Compliance with Federal or State Regulations ................................................. 4 3.0 Alternatives .................................................................................................................... 13 3.1 Actions Common to All Alternatives................................................................ 13 3.2 Alternatives ...................................................................................................... -

Breeding and Feeding Ecology of Bald Eagl~S in the Apostle Island National Lakeshore

BREEDING AND FEEDING ECOLOGY OF BALD EAGL~S IN THE APOSTLE ISLAND NATIONAL LAKESHORE by Karin Dana Kozie A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE College of Natural Resources UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN Stevens Point, Wisconsin December 1986 APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE COMMITTEE OF; Dr. Raymond K. Anderson, Major Advisor Professor of Wildlife Dr. Neil F Professor of Dr. Byron Shaw Professor of Water Resorces ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people donated considerable time and effort to this project. I wish to thank Drs. Neil Payne and Byron Shaw -of-n my graduate ncommittee, for---providing Use fliT comments on this manuscript; my committee chairman, Dr. Ray Anderson, whose support, patience and knowledge will long be appreciated. Special thanks to Chuck Sindelar, eagle biologist for the state of Wisconsin, for conducting aerial surveys, organizing banding crews and providing a vast supply of knowledge and time, and to Ron Eckstein and Dave Evans of the banding crew, for their climbing expertise. I greatly appreciate the help of the following National Park Service personnel: Merryll Bailey, ecologist,.provided equipment, logistical arrangements and fisheries expertise; Maggie Ludwig graciously provided her home, assisted with fieldwork and helped coordinate project activities on the mainland while researchers were on the islands; park ranger/naturalists Brent McGinn, Erica Peterson, Neil Howk, Ellen Maurer and Carl and Nancy Loewecke donated their time and knowledge of the islands. Many people volunteered the~r time in fieldwork; including Jeff Rautio, Al Bath, Laura Stanley, John Foote, Sandy Okey, Linda Laack, Jack Massopust, Dave Ross, Joe Papp, Lori Mier, Kim Pemble and June Rado. -

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements The County Comprehensive Planning Committee Ashland County Staff Gary Mertig Jeff Beirl George Mika Tom Fratt Charles Ortman Larry Hildebrandt Joe Rose Emmer Shields Pete Russo, Chair Cyndi Zach Jerry Teague Natalie Cotter Donna Williamson Brittany Goudos-Weisbecker UW-Extension Ashland County Technical Advisory Committee Tom Wojciechowski Alison Volk, DATCP Amy Tromberg Katy Vosberg, DATCP Jason Fischbach Coreen Fallat, DATCP Rebecca Butterworth Carl Beckman, USDA – FSA Haley Hoffman Gary Haughn, USDA – NRCS Travis Sherlin Nancy Larson, WDNR Stewart Schmidt Tom Waby, BART Funded in part by: Funded in part by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management Under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant #NA15NOS4190094. Cover Page Photo Credit: Ashland County Staff Table of Contents: Background Section Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1-1 Housing ................................................................................................................................................ 2-6 Transportation .................................................................................................................................. 3-24 Utilities & Community Facilities ..................................................................................................... 4-40 Agricultural, Natural & Cultural Resources ................................................................................ -

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2015/972 ON THIS PAGE An opening in an ice-fringed sea cave reveals ice flows on Lake Superior. Photograph by Neil Howk (National Park Service) taken in winter 2008. ON THE COVER Wind and associated wave activity created a window in Devils Island Sandstone at Devils Island. Photograph by Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich (Colorado State University) taken in summer 2010. Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2015/972 Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich Colorado State University Research Associate National Park Service Geologic Resources Division Geologic Resources Inventory PO Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 May 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. -

Fifty Years in the Northwest: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Fifty years in the Northwest L34 3292 1 W. H. C. Folsom FIFTY YEARS IN THE NORTHWEST. WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND APPENDIX CONTAINING REMINISCENCES, INCIDENTS AND NOTES. BY W illiam . H enry . C arman . FOLSOM. EDITED BY E. E. EDWARDS. PUBLISHED BY PIONEER PRESS COMPANY. 1888. G.1694 F606 .F67 TO THE OLD SETTLERS OF WISCONSIN AND MINNESOTA, WHO, AS PIONEERS, AMIDST PRIVATIONS AND TOIL NOT KNOWN TO THOSE OF LATER GENERATION, LAID HERE THE FOUNDATIONS OF TWO GREAT STATES, AND HAVE LIVED TO SEE THE RESULT OF THEIR ARDUOUS LABORS IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE WILDERNESS—DURING FIFTY YEARS—INTO A FRUITFUL COUNTRY, IN THE BUILDING OF GREAT CITIES, IN THE ESTABLISHING OF ARTS AND MANUFACTURES, IN THE CREATION OF COMMERCE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE, THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR, W. H. C. FOLSOM. PREFACE. Fifty years in the Northwest http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.01070 Library of Congress At the age of nineteen years, I landed on the banks of the Upper Mississippi, pitching my tent at Prairie du Chien, then (1836) a military post known as Fort Crawford. I kept memoranda of my various changes, and many of the events transpiring. Subsequently, not, however, with any intention of publishing them in book form until 1876, when, reflecting that fifty years spent amidst the early and first white settlements, and continuing till the period of civilization and prosperity, itemized by an observer and participant in the stirring scenes and incidents depicted, might furnish material for an interesting volume, valuable to those who should come after me, I concluded to gather up the items and compile them in a convenient form. -

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

National Park Service Park News & Planner ‑ 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper of Around the Archipelago Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Pardon the Mess... The Greatest Show on the Big Lake! Closed For Renovation You’d haVE TO GO BACK TO 1929 TO SEE AnytHING LIKE ‑ the 2013 Apostle Islands light station preservation project. Big We know how disappointing a “Closed for happenings at Michigan Island Light: workmen, barges, scaffolding, Renovation” sign can be. We hope that painters, roofers, sawyers, carpenters, glaziers, and masons, all the inconvenience of not climbing the light just busy as beavers. And not just Michigan, but Devils, La Pointe, towers this summer will be rewarded by Outer, and Sand lights too. This is the biggest historic preservation great visitor experiences in the future. project that Apostle Islands National Lakeshore has ever While the National Park Service will work undertaken, and the biggest re-investment in these historic lights to minimize public impacts during the ever made by the federal government. There may NEVER have been light station repair work, some closures a summer this busy at the Apostle Islands’ lighthouses. will be necessary for public safety and to allow workers access to the light stations. Local folks and park visitors have heard rumblings about this for Buildings will be closed to visitation while several years as the planning, design, and contract preparation work work is in progress, as will the adjacent progressed. The lights will be seeing some old friends, and making grounds. The normal volunteer “keepers” some new ones. C3, LLC, a major national construction firm, is the will not be in residence during construction. -

Fishery Bulletin/U S Dept of Commerce National

THE LIFE HISTORY AND TROPHIC RELATIONSHIP OF THE NINESPINE STICKLEBACK, PUNGITIUS PUNGITIUS, IN THE APOSTLE ISLANDS AREA OF LAKE SUPERIOR1 BERNARD L. GRISWOLD2 AND LLOYD L. SMITH, JR.3 ABSTRACT The ninespine stickleback is an important food of juvenile lake trout in the Apostle Islands area. It is the most numerous fish of the area and is distributed in deep waters during the winter and in shallow waters during the summer. Females grow fastel than males. reaching an average total length of 80 mm at age 5. Males live to age 3 and attain an average length of hh mm. Annulus formation on otoliths is complete by mid-July. Seasonal growth is more than half complete by early August: growth of mature females ·is delayed until after spawning. Both sexes mature over a period of 3 yr. Spawning occurs from mid-June to late July. Males apparently do not live as long as females. possibly because of a post-spawning mor tality. Egg number is a linear function of fish length. although this relationship is different for fish from two separate areas. Environmental differences between these areas. which may affect spawning time. possibly cause the differences in fecundity. Significant quantities of maturing eggs atrophy just prior to spawning. a phenomenon which changes the fecundity relationship. Sticklebacks eat a variety of invertebrates. particularly the crustaceans Mrsis re!icra and Pontoporeia alfinis. Food eaten by the stickleback and slimy sculpin is similar. bill the adaptability of both species tends to eliminate serious competition. The lake trout is the only serious predator of stickleback. -

=- ::.: III ~ III ..II L ~ • III ~

z o VI - - '" 0 III > ~ III :E: -VI ..~ VI • III =- ::.: III ~ III ..II l ~ • III ~ - - ---- ------------- GREAT LAKES FISHERY COMMISSION GREAT LAKES FISHERY COMMISSION MEMBERS - 1911 Established by Convention between Canada and the United States for the Conservation of Great Lakes Fishery Resources CANADA UNITED STATES E. W. Burridge W. M. Lawrence F. E. J. Fry N. P. Reed C. J. Kerswill Claude Ver Duin ANNUAL REPORT K. H. Loftus L. P. Voigt for the year 1977 SECRETARIAT C. M. Fetterolf, Jr., Executive Secretary 1451 Green Road A. K. Lamsa, Assistant Executive Secretary Ann Arbor, Michigan, J. Herbert, Fishery Biologist U. S. A. T. C. Woods, Secretary 1980 CONTENTS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL In accordance with ArtiCle IX of the Convention on INTRODUCTION . 1 Great Lakes Fisheries, I take pleasure in submitting ANNUAL MEETING PROCEEDINGS. 2 to the Contracting Parties an Annual Report of the INTERIM MEETING PROCEEDINGS. 9 activities of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission in 1977. APPENDICES A. Summary of Management and Research . 16 Respectfully, B. Summary of Trout, Splake, and Salmon Plantings 25 C. Sea Lamprey Control in the United States . 63 D. Sea Lamprey Control in Canada. 90 L. P. Voigt, Chairman E. Alternative Methods of Sea Lamprey Control. 96 F. Registration-oriented Research on Lampricides, 1977 103 G. Administrative Report for 1977. 110 ~ ANNUAL REPORT FOR 1977 INTRODUCTION A Convention on Great Lakes Fisheries, ratified by the Governments of the United States and Canada in 1955 provided for the establishment of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission. The Commission was given the responsibilities of formulating and coordinating fishery research and management programs, advising govern ments on measures to improve the fisheries, and implementing a program to control the sea lamprey. -

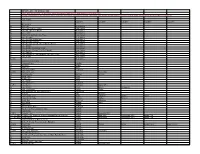

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an Asterisk * Do Not Have Depth Information and Appear with Improvised Contour Lines County Information Is for Reference Only

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an asterisk * do not have depth information and appear with improvised contour lines County information is for reference only. Your lake will not be split up by county. The whole lake will be shown unless specified next to name eg (Northern Section) (Near Follette) etc. LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake St Clair Great Lakes GL (MI) Great Lakes Cedar Creek Reservoir AL Deerwood Lake Franklin AL Dog River Shelby AL Gantt Lake Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Covington AL (GA) Guntersville Lake Lee Harris (GA) AL Highland Lake * Marshall Jackson AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Jordan Lake Blount AL Lake Gantt * Elmore AL Lake Jackson * Covington AL (FL) Lake Martin Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Mitchell Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Chilton Coosa AL Lake Wedowee (RL Harris Reservoir) Tuscaloosa AL Lay Lake Clay Randolph AL Lewis Smith Lake * Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Logan Martin Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Mobile Bay Saint Clair Talladega AL Ono Island Baldwin Mobile AL Open Pond * Baldwin AL Orange Beach East Covington AL Bon Secour River and Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin AL (FL) Pickwick Lake Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL (TN) (MS) Pickwick Lake (Northern Section, Pickwick Dam to Waterloo) Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL (TN) (MS) Shelby Lakes Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Tallapoosa River at Fort Toulouse * Baldwin AL Walter F.