Wisconsin's Historic Shipwrecks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Arctic Nation a U.S

Connecting the United States to the Arctic OUR ARCTIC NATION A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative Cover Photo: Cover Photo: Hosting Arctic Council meetings during the U.S. Chairmanship gave the United States an opportunity to share the beauty of America’s Arctic state, Alaska—including this glacier ice cave near Juneau—with thousands of international visitors. Photo: David Lienemann, www. davidlienemann.com OUR ARCTIC NATION Connecting the United States to the Arctic A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Alabama . .2 14 Illinois . 32 02 Alaska . .4 15 Indiana . 34 03 Arizona. 10 16 Iowa . 36 04 Arkansas . 12 17 Kansas . 38 05 California. 14 18 Kentucky . 40 06 Colorado . 16 19 Louisiana. 42 07 Connecticut. 18 20 Maine . 44 08 Delaware . 20 21 Maryland. 46 09 District of Columbia . 22 22 Massachusetts . 48 10 Florida . 24 23 Michigan . 50 11 Georgia. 26 24 Minnesota . 52 12 Hawai‘i. 28 25 Mississippi . 54 Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. Photo: iStock.com 13 Idaho . 30 26 Missouri . 56 27 Montana . 58 40 Rhode Island . 84 28 Nebraska . 60 41 South Carolina . 86 29 Nevada. 62 42 South Dakota . 88 30 New Hampshire . 64 43 Tennessee . 90 31 New Jersey . 66 44 Texas. 92 32 New Mexico . 68 45 Utah . 94 33 New York . 70 46 Vermont . 96 34 North Carolina . 72 47 Virginia . 98 35 North Dakota . 74 48 Washington. .100 36 Ohio . 76 49 West Virginia . .102 37 Oklahoma . 78 50 Wisconsin . .104 38 Oregon. 80 51 Wyoming. .106 39 Pennsylvania . 82 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE AN ARCTIC NATION? oday, the Arctic region commands the world’s attention as never before. -

Media Release, March 11, 2021 the America's Cup World Series (ACWS

maxon precision motors, inc. 125 Dever Drive Taunton, MA 02780 Phone: 508-677-0520 [email protected] www.maxongroup.us Media release, March 11, 2021 The America’s Cup World Series (ACWS) in December and Prada Cup in January-February were the first time that the AC75 class yachts had been sailed in competition anywhere, including by the competitors themselves. The boat’s capabilities were on full display demonstrating how hard each team has pushed the frontiers of technology, design, and innovation. Over the course of the ACWS, Emirates Team New Zealand was able to observe their competition including current challenger, Luna Rossa Prada Pirelli. Luna Rossa last won the challenger selection series back in 2000 on their first attempt at the America’s Cup. This was the last time Emirates Team New Zealand met the Italians. As history shows Italy has not yet won the cup itself. They look strong and were totally dominant in the Prada Cup Final maintaining quiet confidence, but they are up against a sailing team in Emirates Team New Zealand who are knowledgeable, skilled, and very fast. Emirates Team New Zealand will have collected a great deal of data from Luna Rossa’s racing to date, with which to compare their performance and gain valuable insight into their opponents’ tactics and strategy. The Kiwis approach to the America’s Cup campaign holds a firm focus on innovation. Back in 2017/2018 when the design process began for the new current class of AC75 yachts, the entire concept was proven only through use of a simulator without any prototypes. -

WLSSB Map and Guide

WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY (WLSSB) DEVILS ISLAND NORTH TWIN ISLAND MAP KEY ROCKY ISLAND SOUTH TWIN ISLAND CAT ISLAND WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY APOSTLE ISLANDS BEAR ISLAND NATIONAL LAKESHORE KIOSK LOCATION IRONWOOD ISLAND SCENIC BYWAY NEAR HERBSTER SAILING ON LAKE SUPERIOR LOST CREEK FALLS KIOSKS CONTAIN DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT EACH LOCATION SAND ISLAND VISITOR INFORMATION OUTER ISLAND YORK ISLAND SEE REVERSE FOR COMPLETE LIST µ OTTER ISLAND FEDERAL HIGHWAY MANITOU ISLAND RASPBERRY ISLAND STATE HIGHWAY COUNTY HIGHWAY 7 EAGLE ISLAND NATIONAL PARKS ICE CAVES AT MEYERS BEACH BAYFIELD PENINSULA AND THE APOSTLE ISLANDS FROM MT. ASHWABAY & NATIONAL FOREST LANDS well as a Heritage Museum and a Maritime Museum. Pick up Just across the street is the downtown area with a kayak STATE PARKS K OAK ISLAND STOCKTON ISLAND some fresh or smoked fish from a commercial fishery for a outfitter, restaurants, more lodging and a historic general & STATE FOREST LANDS 6 GULL ISLAND taste of Lake Superior or enjoy local flavors at one of the area store that has a little bit of everything - just like in the “old (!13! RED CLIFF restaurants. If you’re brave, try the whitefish livers – they’re a days,” but with a modern flair. Just off the Byway you can MEYERS BEACH COUNTY PARKS INDIAN RESERVATION local specialty! visit two popular waterfalls: Siskiwit Falls and Lost Creek & COUNTY FOREST LANDS Falls. West of Cornucopia you will find the Lost Creek Bog HERMIT ISLAND Walk the Brownstone Trail along an old railroad grade or CORNUCOPIA State Natural Area. Lost Creek Bog forms an estuary at the take the Gil Larson Nature Trail (part of the Big Ravine Trail MICHIGAN ISLAND mouths of three small creeks (Lost Creek 1, 2, and 3) where System) which starts by a historic apple shed, continues RESERVATION LANDS they empty into Lake Superior at Siskiwit Bay. -

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

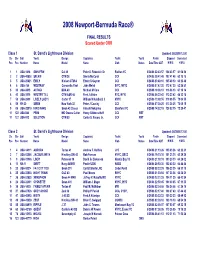

ORR Results Printout

2008 Newport-Bermuda Race® FINAL RESULTS Scored Under ORR Class 1 St. David's Lighthouse Division Updated: 06/28/08 12:00 Cls Div Sail Yacht Design Captain(s) Yacht Yacht Finish Elapsed Corrected Pos Pos Number Name Model Name Club Status Date/Time ADT H M S H M S 1 1 USA-1818 SINN FEIN Cal 40 Peter S. Rebovich Sr. Raritan YC 6/24/08 22:43:57 104 43 57 61 06 38 2 2 USA-40808 SELKIE CTM 38 Sheila McCurdy CCA 6/24/08 20:41:48 102 41 48 62 10 18 3 5 USA-20621 EMILY Nielsen CTM 44 Edwin S Gaynor CCA 6/24/08 23:48:10 105 48 10 63 23 48 4 6 USA-754 WESTRAY Concordia Yawl John Melvin IHYC, NYYC 6/25/08 07:47:20 113 47 20 63 25 51 5 30 USA-3815 ACTAEA BDA 40 Michael M Cone CCA 6/25/08 10:36:13 116 36 13 67 18 14 6 43 USA-3519 WESTER TILL CTM A&R 48 Fred J Atkins EYC, NYYC 6/25/08 06:22:42 112 22 42 68 32 18 7 58 USA-2600 LIVELY LADY II Carter 37 William N Hubbard, III NYYC 6/25/08 13:08:55 119 08 55 70 04 55 8 59 NY-20 SIREN New York 32 Peter J Cassidy CCA 6/25/08 07:38:25 113 38 25 70 05 15 9 86 USA-32510 HIRO MARU Swan 43 Classic Hiroshi Nakajima Stamford YC 6/25/08 14:02:15 120 02 15 73 25 47 11 122 USA-844 PRIM MO Owens Cutter Henry Gibbons-Neff CCA RET 11 122 USA-913 SOLUTION CTM 50 Carter S. -

©Copyright 2010 Clinton Stewart Wright

©Copyright 2010 Clinton Stewart Wright Effects of Disturbance and Fuelbed Succession on Spatial Patterns of Fuel, Fire Hazard, and Carbon; and Fuel Consumption in Shrub-dominated Ecosystems Clinton Stewart Wright A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2010 Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Forest Resources University of Washington Graduate School This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a doctoral dissertation by Clinton Stewart Wright and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Chair of the Supervisory Committee: _______________________________________________________ David L. Peterson Reading Committee: _______________________________________________________ James K. Agee _______________________________________________________ Donald McKenzie _______________________________________________________ David L. Peterson Date: _____________________________________ University of Washington Abstract Effects of Disturbance and Fuelbed Succession on Spatial Patterns of Fuel, Fire Hazard, and Carbon; and Fuel Consumption in Shrub-dominated Ecosystems Clinton Stewart Wright Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor David L. Peterson School of Forest Resources A state and transition approach was used to model and map fuelbed, fire hazard, and carbon change under different management and fire regimes for the Okanogan- Wenatchee National Forest in central Washington. Landscape metrics showed different patterns of change over time depending upon the metric considered and the fire and management regime modeled. Fuelbeds characteristic of older forest conditions became more common during the first ~100 years of simulation (coverage increased 5 – 20%), except in those locations where wet forests subject to stand-replacement fire occur (coverage decreased 6 – 12%). -

LIGHTHOUSES Pottawatomie Lighthouse Rock Island Please Contact Businesses for Current Tour Schedules and Pick Up/Drop Off Locations

LIGHTHOUSE SCENIC TOURS Towering over 300 miles of picturesque shoreline, you LIGHTHOUSES Pottawatomie Lighthouse Rock Island Please contact businesses for current tour schedules and pick up/drop off locations. Bon Voyage! will find historic lighthouses standing testament to of Door County Washington Island Bay Shore Outfitters, 2457 S. Bay Shore Drive - Sister Bay 920.854.7598 Door County’s rich maritime heritage. In the 19th and Gills Rock Plum Island Range Bay Shore Outfitters, 59 N. Madison Ave. - Sturgeon Bay 920.818.0431 early 20th centuries, these landmarks of yesteryear Ellison Bay Light Pilot Island Chambers Island Lighthouse Lighthouse Classic Boat Tours of Door County, Fish Creek Town Dock, Slip #5 - Fish Creek 920.421.2080 assisted sailors in navigating the lake and bay waters Sister Bay Rowleys Bay Door County Adventure Rafting, 4150 Maple St. - Fish Creek 920.559.6106 of the Door Peninsula and surrounding islands. Today, Ephraim Eagle Bluff Lighthouse Cana Island Lighthouse Door County Kayak Tours, 8442 Hwy 42 - Fish Creek 920.868.1400 many are still operational and welcome visitors with Fish Creek Egg Harbor Baileys Harbor Door County Maritime Museum, 120 N. Madison Ave. - Sturgeon Bay 920.743.5958 compelling stories and breathtaking views. Relax and Old Baileys Harbor Light step back in time. Plan your Door County lighthouse Baileys Harbor Range Light Door County Tours, P.O. Box 136 - Baileys Harbor 920.493.1572 Jacksonport Carlsville Door County Trolley, 8030 Hwy 42 - Egg Harbor 920.868.1100 tour today. Sturgeon Bay Sherwood Point Lighthouse Ephraim Kayak Center, 9999 Water St. - Ephraim 920.854.4336 Visitors can take advantage of additional access to Sturgeon Bay Canal Station Lighthouse Fish Creek Scenic Boat Tours, 9448 Spruce St. -

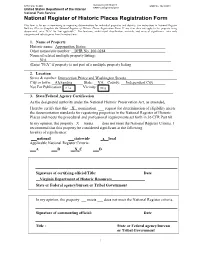

Appomattox Statue Other Names/Site Number: DHR No

NPS Form 10-900 VLR Listing 03/16/2017 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior NRHP Listing 06/12/2017 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Appomattox Statue Other names/site number: DHR No. 100-0284 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Intersection Prince and Washington Streets City or town: Alexandria State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements -

America's Cup in America's Court: Golden Gate Yacht Club V. Societe Nautique De Geneve

Volume 18 Issue 1 Article 5 2011 America's Cup in America's Court: Golden Gate Yacht Club v. Societe Nautique de Geneve Joseph F. Dorfler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph F. Dorfler, America's Cup in America's Court: Golden Gate Yacht Club v. Societe Nautique de Geneve, 18 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 267 (2011). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol18/iss1/5 This Casenote is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Dorfler: America's Cup in America's Court: Golden Gate Yacht Club v. Socie Casenotes AMERICA'S CUP IN AMERICA'S COURT: GOLDEN GATE YACHT CLUB V. SOCIETE NAUTIQUE DE GENEVD I. INTRODUCTION: "THE OLDEST CONTINUOUS TROPHY IN SPORTS" 2 One-hundred and thirty-seven ounces of solid silver, standing over two feet tall, this "One Hundred Guinea Cup" created under the authorization of Queen Victoria in 1848 is physically what is at stake at every America's Cup regatta.3 However, it is the dignity, honor, and national pride that attach to the victor of this cherished objet d'art that have been the desire of the yacht racing community since its creation. 4 Unfortunately, this desire often turns to envy and has driven some to abandon concepts of sportsmanship and operate by "greed, commercialism and zealotry."5 When these prin- ciples clash "the outcome of the case [will be] dictated by elemental legal principles."6 1. -

Federal Judge Issues Ruling on Special Events Permit Dispute

April 4, 2019 Federal judge issues ruling on special What’s New This Week Page 2/Local events permit dispute Sacred eagle minished such that feather the village may presentation enforce the Or- dinance on those lands not held in Page 46/Sports Federal Court Judge William Gries- trust by the United ONHS softball bach issued a ruling in the ongoing dis- States for the ben- team gains expe- pute between the Oneida Nation and the efit of the Nation.” rience Village of Hobart on March 28 regard- Following the ing the village’s attempts to enforce a decision, the Onei- special events permit ordinance on the da Nation issued a Page 9/Local Nation for its annual Big Apple Fest response to Judge Annual GTC meeting convened event. Griesbach’s rul- ing: In his ruling, Judge Griesbach con- PO Box 365 - Oneida, WI 54155 Oneida Nation KALIHWISAKS “Today, feder- cluded that the Treaty of 1838 created Kali file photo a reservation that has not been dises- al district court Judge William Griesbach ruled that the disestablished. tablished. However, Griesbach further Unfortunately, Judge Griesbach also wrote “Congress’s intent to at least di- 1838 Treaty with the Oneida created the Oneida Reservation as lands held in minish the Reservation is manifest in • See 7, the Dawes Act and the Act of 1906” and common for the Oneida Nation, and that “the Nation’s reservation has been di- the Oneida Reservation has never been Federal ruling Students participate in maple syrup boil down Kali photo/Christopher Johnson Students at the Oneida Nation High School and Elementary School continue to learn the cultural significance of the maple syrup-making process. -

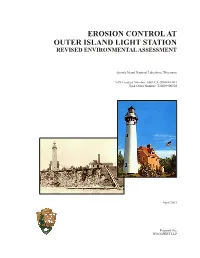

Erosion Control at Outer Island Light Station, Revised Environmental

EROSION CONTROL AT OUTER ISLAND LIGHT STATION REVISED ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Apostle Island National Lakeshore, Wisconsin NPS Contract Number: 1443-CX-2000-99-003 Task Order Number: T20009900328 April 2003 Prepared By: WOOLPERT LLP NATIONAL PARK SERVICE EROSION CONTROL AT OUTER ISLAND LIGHT STATION REVISED ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Prepared By: Woolpert LLP 409 East Monument Avenue Dayton, Ohio 45402 April 2003 Outer Island Environmental Assessment 1 4/03 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 Purpose and Need........................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Background .................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Project Background and Scope ......................................................................... 3 2.2 Relationship to Other Actions and Plans........................................................... 4 2.3 Issues................................................................................................................. 4 2.4 Compliance with Federal or State Regulations ................................................. 4 3.0 Alternatives .................................................................................................................... 13 3.1 Actions Common to All Alternatives................................................................ 13 3.2 Alternatives ...................................................................................................... -

Door County Lighthouse Map

Door County Lighthouse Map Canal Station Lighthouse (#3) Sherwood Point Lighthouse (#4) Compliments of the Plum Island Range Light (#6) www.DoorCounty.com Pilot Island Lighthouse (#9) Door County Lighthouses # 2 Eagle Bluff Lighthouse Location: Follow Hwy. 42 to the North end of The Door County Peninsula’s 300 miles of Fish Creek to the entrance of Peninsula State shoreline, much of it rocky, gave need for th Park. You must pay a park admission fee the lighthouses so that sailors of the 19 when you enter the park. Inquire about the th and early 20 centuries could safely directions to the lighthouse at the park’s front navigate the lake and bay waters around entrance. History: The lighthouse was the Door peninsula & surrounding islands. established in 1868 and automated in 1926. Restoration began in 1960 by the Door County # 1 Cana Island Lighthouse Historical Society. The lighthouse has been open for tours since 1964. Welcome: Tours are $4 for adults, $1 for students, and children 5 and under are free. Tour hours are daily from 10-4, late May through mid-October. Tours depart every 30 minutes. The park maintains a parking lot and restrooms adjacent to the grounds. Information: Phone (920) 839-2377 or online at www.EagleBluffLighthouse.org. Maintained and operated by the Door County Historical Society. Tower is only open to public during Lighthouse Walk weekend in May # 3 Canal Station / Pierhead Light Location: Take County Q at the North edge of Baileys Harbor to Cana Island Rd. two and Location: This fully operating US Coast a half miles (Note: Sharp Right Turn on Cana Guard station is located at the Lake Michigan Island Rd).