Downloadfileaction?Id¼68047

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

A Bibliography on Indians in South Africa : a Guide to Materials at the Documentation Centre

.A BIBLIOGRAPHY ON INDIANS IN SOUTH AFRICA : A GUIDE TO MATERIALS AT THE DOCUMENTATION CENTRE . A compiled by K CHETTY Documentation Centre Series, no 1 1990 University of Durban- Westville ISBN: 0-947445-02-1 INT ROD UCT 10M The FXblicatlon of this guide arises from a strong need to make known the nature and extent of the PUBLISHED AND UNPUBLISHED materials at the Docunentatlon Centre of the University of Durban-~estville on the subject 'The Indian In South Africa'. The Centre's materials Include books, manuscripts, theses, audio-visusl material, newspapers, serials and general archive material. This first bibliography In the Docunentation Centre Series concentrates on the variety of materials available UNDER EACH CLASSIFICATION end sorted by BRM (Blbl iographlc Record Nunber) - see Section A. Only entries of type "Manuscript" have been Isolated from the coq:xJterlsed records and this aCCOU'lts for the "missing" flUR)ers In the sequence of BRN's listed. The BRN Is a unique identifier for the record and this flUR)er Is most suited to serve as a LINK to sections (B-F). This link Is established by quoting only the BRN In these sections (B-F) so that this flUR)er can be used to POINT TO the FUll ENTRY In Section A. The ' linking' technique ~loyed has enabled the Inclusion of many indexes (Section B-G), which serve as cross references to the Primary Record Description (Section A), consisting of a title,. remarks, dates, sUllll8ry, classification nurber and the BRN. The Indexes included are as follows INDEX SECTION MAIN INDEX A TITLE INDEX -

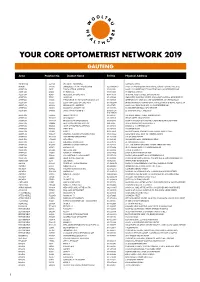

Your Core Optometrist Network 2019 Gauteng

YOUR CORE OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2019 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 9071046 SHOPS -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

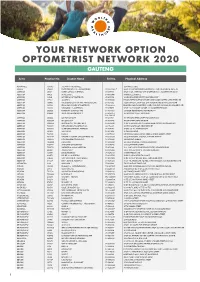

Your Network Option Optometrist Network 2020 Gauteng

YOUR NETWORK OPTION OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2020 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 -

Collective Violence and the Agrarian Origins of South African Apartheid, 1900–1948 John Higginson Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04648-1 - Collective Violence and the Agrarian Origins of South African Apartheid, 1900–1948 John Higginson Index More information Index aankoord , 40 and 1914 Rebellion, 345 African agriculture, 6 and Afrikaner youth, 354 African irregulars and the “shirt” movements, 26 , 346 African soldiers fi ghting under British or apartheid government of 1948, 137 their own leaders during South African Apartheid Manifesto, 341 War, 33 , 37 , 46 , 49 , 50 , 59 , 61 , 65 , 66 , 74 , as a “network of rackets,” 351 77 , 96 , 99 , 101 , 114 , 350 “grand apartheid,” 20 African peasant smallholders, 31 , 37 , 58 , 102 protracted demise, 358 African peasants arme blankedom . See bywoners: during 1914 Rebellion, 164 poor whites during aftermath of South African War, Armeburgersfonds Applikasie Boek 84 , 101 Poor Burgher Relief, 44 during South African War, 62 , 65 , 67 , 68 Atkins, Keletso, 4 African protest, 4 Afrikaanse Ekonomiese Boere Verbond , 185 Baden-Powell, R. S. S. General, 52 , 53 , 55 , 57 , Afrikaanse Nasionale Studentbond , 321 58 , 97 , 319 Alberts, Sarel Francois formation of South African captured at Swartsruggens in December Constabulary, 68 1914, 173 speculation on future of South African early planner of 1914 Rebellion, 165 Constabulary, 97 fl ight to rebel stronghold Steenbokfontein, Bailey, Abe Sir, 294 November 1914, 172 bangziekte or “shell shock,” 46 leader of 1914 Rebellion, 161 Barnard, Willem, 65 Nationalist M. P. from Magaliesberg in adolescent guerrilla soldier and murderer of 1932, 291 African transport rider Franz, December on trial with Grobler and van Broekhuizen 1900, 63 in 1915, 180 Barnato, Barney, 36 sold farm in Thabazimbi, June 1905, 92 Barrett, E. -

The City of Johannesburg Is One of South Africa's Seven Metropolitan Municipalities

NUMBER 26 / 2010 Urbanising Africa: The city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) By: Editors Authors: Alonso Ayala Peter Ahmad Ellen Geurts Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 1 Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) Authors: Peter Ahmad Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs Editors: Alonso Ayala Ellen Geurts IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 2 Introduction This working paper contains a selection of 7 articles written by participants in a Refresher Course organised by IHS in August 2010 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The title of the course was Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited - Ensuring liveable and sustainable inner-cities in Southern African countries: making it work for the poor. The course dealt in particular with inner-city revitalisation in Southern African countries, namely South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Inner-city revitalisation processes differ widely between the various cities and countries; e.g. in Lusaka and Mbabane few efforts have been undertaken, whereas Johannesburg in particular but also other South Africa cities have made major investments to revitalise their inner-cities. The definition of the inner-city also differs between countries; in Lusaka the CBD is synonymous with the inner-city, whereas in Johannesburg the inner-city is considered much larger than only the CBD. -

Le Solidarity Movement Et La Restructuration De L'activisme Afrika

Université de Montréal « Un peuple se sauve lui-même » Le Solidarity Movement et la restructuration de l’activisme afrikaner en Afrique du Sud depuis 1994 par Joanie Thibault-Couture Département de science politique, Faculté des Arts et des Sciences Thèse présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de doctorat en science politique Janvier 2017 © Joanie Thibault-Couture 2017 Résumé Malgré la déliquescence du nationalisme afrikaner causée par la chute du régime de l’apartheid et la prise du pouvoir politique par un parti non raciste et non ethnique en 1994, nous observons depuis les années 2000, un renouvèlement du mouvement identitaire afrikaner. L’objectif de cette thèse est donc de comprendre l’émergence de ce nouvel activisme ethnique depuis la transition démocratique. Pour approfondir notre compréhension du phénomène, nous nous posons les questions suivantes : comment pouvons-nous expliquer le renouvèlement de l’activisme afrikaner dans la « nouvelle » Afrique du Sud ? Comment sont définis les nouveaux attributs de la catégorie de l’afrikanerité ? Comment les élites ethnopolitiques restructurent-elles leurs stratégies pour assurer la pérennité de la catégorie dans l’Afrique du Sud post-apartheid ? Qu’est-ce que la résurgence d’une afrikanerité renouvelée nous apprend sur l’état de la cohésion sociale en Afrique du Sud et sur la mobilisation ethnolinguistique en général ? La littérature sur le mouvement post-apartheid fait consensus sur la disparition du nationalisme afrikaner raciste, mais offre peu d’analyses empiriques et de liens avec les nombreux écrits sur le mouvement nationaliste afrikaner pour comprendre les dynamiques de ce nouveau phénomène et effectue peu de liens avec les nombreux écrits sur le mouvement nationaliste afrikaner. -

Competing Marxist Theories on the Temporal Aspects of Strike Waves: Silver’S Product Cycle Theory and Mandel’S Long Wave Theory

Competing Marxist Theories on the Temporal Aspects of Strike Waves: Silver’s Product Cycle Theory and Mandel’s Long Wave Theory Eddie Cottle, Rhodes University, South Africa ABSTRACT Despite the profound changes in capitalist development since the industrial revolution, strike waves and mass strikes are still a feature of the twenty-first century. This article examines two Marxist theories that seek to explain the temporal aspects of strike waves. In the main, I argue that Silver’s product cycle theory, suffers from an over-determinism, and that turning point strike waves are not mainly determined by lead industries. Mandel’s long wave theory argues that technological innovations tend to cluster and thus workers in different industries feature prominently in strike waves. By re-examining and comparing two competing Marxist theories on the temporality of strike waves and turning points, I will attempt to highlight the similarities but also place emphasis on where the theories differ. I examine the applicability of the theories to the South African case, and reference recent world events in order to ascertain the explanatory power of the competing theories. In the main I argue that Silver’s product cycle lead theory does not fit the South African experience. KEYWORDS turning point strike waves; product cycle; long waves; capitalism Introduction Despite the profound changes in capitalist development since the industrial revolution, strike waves and mass strikes are still a feature of the twenty-first century. This article examines two Marxist theories that seek to explain the temporal aspects of strike waves. Both theories are especially concerned with strikes that alter labour–capital relations, or turning points, and both focus on the world-historical scale. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Chapter Introduction A prominent aspect of topical urban planning and development thought focuses on the need to valorise, acknowledge and adequately represent certain groups of people that have been marginalised in the contemporary metropolis (Sandercock, 1998; Sassen, 1996). These include ethnic minorities, immigrants, poor people, women and people with disabilities, amongst other groupings. It is argued that the recognition of these members of society is essential in terms of urban planning and governance, and in their servicing the corporate centre of the economy. This is indeed more important when considering that diversity continues to flourish in the world today even though economic globalisation appears to be on its way toward creating an integrated world market (Smith, 2003, 7). This diversity, originating from either an economic, social or political ethos, lends itself in large part to the presence of marginalised communities, such as ethnic minorities and immigrants, in cities around the world. Sandercock (1998, 164) aptly describes this scenario as follows: “Multi-ethnic, multi-racial and multi-national populations are becoming a dominant characteristic of cities and regions across the globe,…”. Most major, diverse cities around the world can thus be thought of as being cosmopolitan metropolises. Harrison (in Harrison et al (eds.), 2003, 22) states that within the postmodernist framework, fragmentation becomes diversity and is something to be celebrated rather than conquered, and that it is not an evil. However, if viewed otherwise, fragmentation has strong negative connotations, hence creating the potential for conflict with the presence of diversity. Whatever the discourse, diversity is important in planning, either as something to defend or as a valuable resource to make use of. -

6 X 10.5 Three Line Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89873-7 - The Legacies of Law: Long-Run Consequences of Legal Development in South Africa, 1652-2000 Jens Meierhenrich Index More information Index Abel, Richard, 209, 256, 326 and the Truth and Reconciliation Ackerman, Laurie, Justice, 172 Commission of South Africa administrative law, 65, 75, 227 (TRC), 205–207 Administrator, Transvaal v. Traub and township unrest, 179 (1989), 163 and township youth, 179 African customary law leaders and the law, 226–231, 262–263 influence of on South African law, 92 African nationalism, 248, 255 African National Congress (ANC), 7, 8, Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging 9, 27, 117, 122, 138, 147, 150, 152, (AWB), 27 153, 169, 182, 183, 184, 196, 259, and constitutional design, 199 261, 267, 268, 272, 282, 289. Afrikaners, 84, 86, 88, 95, 96, 97, 98, See also South African Native 101, 103, 170, 177, 188, 227, National Congress (SANNC) 238, 239, 241, 242, 243, 246, 247, and apartheid’s endgame, 191–207, 248, 261 263, 276–277 Alessandri, Arturo, 297 and constitutional design, 197–205 Allende, Salvador, 298, 308 and electoral design, 196–197 Allott, Philip, 15 and Ethiopianism, 255–258 analytic narratives, 2, 9, 11, 195, 290, and National Front for the Liberation 291, 310, 327 of Angola (FNLA), 176 ANC. See African National Congress and National Union for the Total (ANC) Independence of Angola Anglican Church of the Province (UNITA), 176 (CPSA), 248 and Nelson Mandela, 279–281 apartheid, 3, 4, 10, 11, 12, 15, 47, 52, 79, and Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), 122 83, 86, 87, 101, -

From Recolonised to Decolonised South African Economics

From Recolonised to Decolonised South African Economics Patrick Bond ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6657-7898 Gumani Tshimomola ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8129-0905 Abstract Replacing a neocolonial project of financial control by neoliberal forces, with one that represents genuine economic decolonisation has never been more urgent in South Africa and everywhere. The essence of the critique we offer is that the intellectual roots of a decolonising analysis and strategy can be found not only in the classical anti-colonial/capitalist/imperialist analysis of Marx and Luxemburg, but also in works by Africa’s leading decolonial political economist, Samir Amin, as well as by some of the South African writers who specified race-class-gender-environmental oppressions. The main problem in changing economic policy, though, is the ongoing power of a local agent of economic colonisation, the Treasury (regardless of who happens to be Finance Minister). In one recent exception, however, students demanded an extra R40 billion be added to the annual budget, and their power of protest was sufficient to defeat Treasury neoliberals. In other sectoral struggles, the students’ lessons about broader-based coalitions and national targets, as well as the need for much deeper-reaching and militant critique (in the spirit of Amin) have yet to be learned. Ultimately a much more comprehensive critique of how South Africa was economically recolonised may well be necessary, one based on ideologies that link other intellectual and activist campaigns