Chapter 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliography on Indians in South Africa : a Guide to Materials at the Documentation Centre

.A BIBLIOGRAPHY ON INDIANS IN SOUTH AFRICA : A GUIDE TO MATERIALS AT THE DOCUMENTATION CENTRE . A compiled by K CHETTY Documentation Centre Series, no 1 1990 University of Durban- Westville ISBN: 0-947445-02-1 INT ROD UCT 10M The FXblicatlon of this guide arises from a strong need to make known the nature and extent of the PUBLISHED AND UNPUBLISHED materials at the Docunentatlon Centre of the University of Durban-~estville on the subject 'The Indian In South Africa'. The Centre's materials Include books, manuscripts, theses, audio-visusl material, newspapers, serials and general archive material. This first bibliography In the Docunentation Centre Series concentrates on the variety of materials available UNDER EACH CLASSIFICATION end sorted by BRM (Blbl iographlc Record Nunber) - see Section A. Only entries of type "Manuscript" have been Isolated from the coq:xJterlsed records and this aCCOU'lts for the "missing" flUR)ers In the sequence of BRN's listed. The BRN Is a unique identifier for the record and this flUR)er Is most suited to serve as a LINK to sections (B-F). This link Is established by quoting only the BRN In these sections (B-F) so that this flUR)er can be used to POINT TO the FUll ENTRY In Section A. The ' linking' technique ~loyed has enabled the Inclusion of many indexes (Section B-G), which serve as cross references to the Primary Record Description (Section A), consisting of a title,. remarks, dates, sUllll8ry, classification nurber and the BRN. The Indexes included are as follows INDEX SECTION MAIN INDEX A TITLE INDEX -

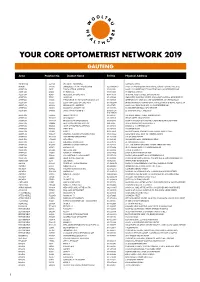

Your Core Optometrist Network 2019 Gauteng

YOUR CORE OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2019 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 9071046 SHOPS -

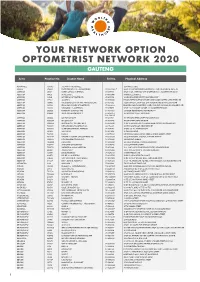

Your Network Option Optometrist Network 2020 Gauteng

YOUR NETWORK OPTION OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2020 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 -

The City of Johannesburg Is One of South Africa's Seven Metropolitan Municipalities

NUMBER 26 / 2010 Urbanising Africa: The city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) By: Editors Authors: Alonso Ayala Peter Ahmad Ellen Geurts Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 1 Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) Authors: Peter Ahmad Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs Editors: Alonso Ayala Ellen Geurts IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 2 Introduction This working paper contains a selection of 7 articles written by participants in a Refresher Course organised by IHS in August 2010 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The title of the course was Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited - Ensuring liveable and sustainable inner-cities in Southern African countries: making it work for the poor. The course dealt in particular with inner-city revitalisation in Southern African countries, namely South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Inner-city revitalisation processes differ widely between the various cities and countries; e.g. in Lusaka and Mbabane few efforts have been undertaken, whereas Johannesburg in particular but also other South Africa cities have made major investments to revitalise their inner-cities. The definition of the inner-city also differs between countries; in Lusaka the CBD is synonymous with the inner-city, whereas in Johannesburg the inner-city is considered much larger than only the CBD. -

Find Your GP & Pharmacy in Gauteng

Find your GP & Pharmacy in Gauteng FIND THE MOST RECENT LIST OF GP’S ON THE WEBSITE www.yourcarenetwork.co.za JUNE 2021 List of Doctors Practice Practice Doctor Address Area Doctor Address Area Landline Landline Dr A Mabuza 3936 Natal sand Street, Riverside view Ext 35 Fourways 011 464 5030 Dr BH Modi 126 Jeppe Street, Johannesburg Johannesburg 011 833 1588 Dr SS Mlambo 11174 Freedom Drive, Thuthukani Centre, Ivory park Midrand 011 204 0461 Dr E Joosuf Shop 16 Burton court, Hillbrow, Johannesburg Johannesburg 011 725 2281 Dr U Pillay First Floor, 10 Halfway House Centre, Halfway House Midrand 011 315 0660 Dr KB Daya 127 Louis Botha Avenue, Fellside, Johannesburg Johannesburg 011 483 2820 Dr CW Dr N Nhlapo 21 Dane Road, Glen Austin, Midrand Midrand 011 026 6435 4th Floor Medical Chambers, RH Rand Clinic, Berea Johannesburg 011 333 2408 Muzamhindo Dr Rakumakoe 128 Fox Street, Marshaltown, Johannesburg CBD Johannesburg 010 1419 500 Fox street Dr MT Sandy 170 Bram Fischer Drive, The Gardens Shopping Mall Randburg 011 886 8930 Dr AI Mansoor 112 Claim Street, Hillbrow, Johannesburg Johannesburg 011 484 2176 Dr R Ndhlovu Shop 304, Lower level, Randburg square, Pretoria Street Randburg 011 886 1242 Dr A Alekar 51 Commando Road, Industria west, Johannesburg Johannesburg 011 474 1426 Dr ZM Majova Shop 14, Centre point, 315 Pretoria Avenue, Ferndale Randburg 011 326 2028 Dr Y Mithal 4 Kort Street, Johannesburg Johannesburg 011 834 5945 Dr L Badenhorst 2 Eaton Avenue, Bryanston Bryanston 011 706 7006 Dr N Hlungwane 27 De Beer street, Kenlaw building, -

Downloadfileaction?Id¼68047

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za (Accessed: Date). FORGED COMMUNITIES: A SOCIOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF IDENTITY AND COMMUNITY AMONGST IMMIGRANT AND MIGRANT COMMUNITIES IN FORDSBURG by PRAGNA RUGUNANAN Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree D Litt et Phil in Sociology FACULTY OF HUMANITIES at the DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR SAKHELA BUHLUNGU CO-SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR RIA SMIT July 2015 DECLARATION I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work for which I present for examination. _______________________________ Pragna Rugunanan July 2015 P a g e | ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Embarking on a doctoral thesis is an arduous journey and the ultimate discovery is the discovery of the self. -

A Review of the Domestic Impact

CREATIVE COMPONENT..........................................................................................2 1. THEORETICAL INTRODUCTION...................................................................36 1.1 Introduction......................................................................................................36 1.2 Historical Background of Fietas ......................................................................38 2. WHY FIETAS?....................................................................................................40 2.1 Fietas as the Choice for the Creative Work .....................................................40 2.1 Telling ‘Untold’ Stories ...................................................................................41 2.3 The Relationship between Place and Identity..................................................43 3. FINDING FORM.................................................................................................46 4. MEMORY AND MEMORIALISATION ...........................................................48 5. WRITING AND REVISING...............................................................................52 5.1 Types of Narratives..........................................................................................52 5.1.1 Mapping Fietas ............................................................................................53 5.1.2 Fietas............................................................................................................54 5.1.3 Ghalieb on 11th.............................................................................................55 -

Companies Act: Incorporations, Registrations, Changes of Names, Dissolutions, Deregistrations and Conversions from Close Corpora

Deregistration of Companies • Deregistrasie Van Maatskappye-A List/Lys From 01/01/2001 To 18/03/2004 • Van 01/01/2001 Tot 18/03/2004 I~ Number Enterprise name Address SIC code z Nommer Naam van onderneming Adres SNK kode 0 I'J M 1957002349 WESTERN DEEP LEVELS 11 DIAGONAL STREET, JOHANNESBURG, 2001 0 m..... M1957003592 PRINSLOO LANDGOED 0 M1957003975 ROWAN ENTERPRISES 36 SIR LOWRY ROAD, CAPE TOWN, 8001 0 ~ M1958001487 AMALGAMATED TOBACCO CORPORATION (SOUTH AFRICA) 34 ALEXANDER STREET, STELLENBOSCH, 7600 0 M1958001618 MILLER WEEDON TRAVEL (JOHANNESBURG) 3RD FLOOR, KILLARNEY MALL, RIVIERA ROAD, KILLARNEY, 2193 7 M1959000874 M H AND E LURIE FOURTH FLOOR ALOE GROVE, 196 LOUIS BOTHA AVENUE, HOUGHTON ESTATE, 0 JOHANNESBURG, 2198 M1959001674 MUGGANSONS 1ST FLOOR PERMANENT BUILDING, 25 JONES STREET, KIMBERLEY, 8301 0 M1959003141 SABAAN BOERDERY 53 FRANS HALS STREET, PETERVALE, SANDTON, 2146 0 M1959003360 W 0 B PROPERTIES CHARLES $TREET, GREAT BRAK RIVER, 6525 0 M 1960000053 BAND 0 FARMING AND IRRIGATIONAL EQUIPMENT 19TH FLOOR, 8 P CENTRE, THIBAULT SQUARE, CAPE TOWN, 8001 0 M1960001323 STEMATINVESTMENTS 12 CLYDE STREET, KNYSNA, 6570 0 Gl M1962000473 DRUPO 11 OLEN LANE, POTCHEFSTROOM, 2520 0 0 M 1962000878 CROWN-INTERNATIONAL 85 BUTE LANE, SANDOWN, SANDTON, 2146 0 < 0 m M1962001019 P C DATA PRODUCTS SA 13 WELLINGTON ROAD, PARKTOWN, 2193 ll M1962001748 FLUOR PROPERTIES 1 KIKUYU ROAD, SUNNINGHILL, SANDTON, 2157 8 z M1962004717 MACNEL ESTATES CRESCENT HOUSE, 1 D'ARCY STREET, KIMBERLEY, 8301 0 !5:: M1963001193 LOUCOUTANTI 7TH fLOOR ANCHOR PLEIN, 100 -

ADT LIVE BASE 25 June 2010

Site Name Address The Glen Branch CNR LETABA & ORPEN ROADS, OAKDENE Balfour Park Branch CNR LOUIS BOTHA & ATHOL AVENUE, BALFOUR Goldenwalk Branch 141 VICTORIA STREET, GERMISTON Kurgersdorp PRESIDENT SQUARE S/C, CNR PAARDEKRAAL AND PRETORIA ST, KRUGERSDORP Festival Mall SHOP 90-91,FESTIVAL MALL SHOPPING CENTRE Rosebank cnr Tyrwhitt and Cradock Avenue, Rosebank Cresta Centre Cresta S/C, cnr Beyers Naude and Weltevreden Drive Ladysmith Kwazulu-Natal 198 Murchison St, Ladysmith Alberton CR VOORTREKKER & FORE ST , ALBERTON Bankcity 3 1ST PLACE, HARRISON & KERK Orkney cnr Shakespeare and Fletch Rd, Orkney Karaglen SHOP U2,KARAGLEN S/CENTRE,EDENVALE Musina 14 NATIONAL ROAD Hammanskraal RENBRO CENTRE Vaal Mall SHOP 120,VAAL MALL,VANDERBIJLPARK Village at Horizon SHOP NO26/27,THE VILLAGE@HORIZON S/C Kremetart Centre SHOP 12 & 13, KREMETART CENTRE, BRITS East Rand Mall SHOP 101 E.R.M. BUILDING Pretoria North 526 RACHEL DE BEER STREET Middelburg 19 MARKET STREET Vanderbijlpark 4 PRESIDENT KRUGER STREET Wilkoppies SHOP 3, AMETIS STR, WILKOPPIES Mbhizana MAIN STREET,MBIZANA Thibault 2 LONG STREET The Reds CNR ROOIHUISKRAAL & HENDRIK VERWOERD DR Mount Frere MAIN STREET Alice Branch SHOP 4 & 5 KANTU CENTRE, ALICE Fountains Mall Branch SHOP G51 FOUNTAINS MALL, JEFFREYS BAY Gezina SHOP11,GEZINA GALLARIES,MICHAEL BRINK ST Sandton City Sandton City Mall Potchefstroom SHOP 51 & 52, MOOI RIVIER MALL Nigel Cnr R42 and Rhodes Avenue, Nigel Angelo Shopping Centre 011 814 8266 Bathopele Shop No 1 Game Centre, Nelson Mandela Drive, Mafikeng Tembisa Mall SHOP A1,CNR -

Asiatic Bazaar AUGUST.Indd

STORIES FROM THE ASIATIC BAZAAR Muthal Naidoo Stories from the Asiatic Bazaar ISBN: 0-620-35222-1 ©Muthal Naidoo October 2005 email: [email protected] Layout and Design: Quba Design and Motion Stories from the Asiatic Bazaar Muthal Naidoo CONTENTS Foreword Acknowledgments 1. Early Pretoria 2. Child of the Location: Boma 3. Following the Heart: Sinthumbi and Poppie 4. Satyagrahi: Thayanayagie Pillay (Thailema) 5. Passive Resister: Maniben Sita 6. Singer of the Majalis: Amina Jeeva 7. The Spirit of Independence: Thanga Kollapen 8. Filmmaker of the Location: Omarjee Suliman 9. A Vanished Community: ‘The Khojas’ 10. Seeking the Beloved: Jeram and Jaydevi 11. A Family of Sportsmen: Dhiraj Soma and Sons 12. Bioscopes and Achaar: The Chetty Brothers 13. Aluta Continua: Apmai Dawood Glossary Interviews References Addendum: An Outline of Indian South African History 1860 – 1960 5 FOREWORD emories, like dreams, having escaped from space and Mtime, follow a chronology of significance to the heart. The remembering mind isolates events, enhances them, and removes inconsistencies that indicate a more human, less exalted existence. In these biographical stories, based largely on memories with their built-in filters, those more fascinating human elements may have been omitted. As the act of recording requires authentication, it becomes necessary to return memories to specific historical, political, economic and social contexts in order to find congruence with actual happenings. In the process, wisps of memory, clues to forgotten events, take on substantial form when they connect with happenings described in little known written accounts. Such books and papers, no longer in circulation and gathering dust, suddenly assume new significance and personal collections become treasure troves. -

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON

THE PROVINCE OF DIE PROVINSIE VAN UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG IN GAUTENG Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON Selling price • Verkoopprys: R2.50 Other countries • Buitelands: R3.25 PRETORIA Vol. 26 29 JULY 2020 No. 125 29 JULIE 2020 We oil Irawm he power to pment kiIDc AIDS HElPl1NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure ISSN 1682-4525 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 00125 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 452005 2 No. 125 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, 29 JULY 2020 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. CONTENTS Gazette Page No. No. GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 476 Gauteng Gambling Act (4/1995), as amended: Hearing by the Gauteng Gambling Board in respect of applications for licences ..................................................................................................................................... 125 3 This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za PROVINSIALE KOERANT, BUITENGEWOON, 29 JULIE 2020 No. 125 3 GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS NOTICE 476 OF 2020 476 Gauteng Gambling Act (4/1995), as amended: Hearing by the Gauteng Gambling Board in respect of applications for licences 125 GAUTENG GAMBLING BOARD HEARING BY THE GAUTENG GAMBLING