Asiatic Bazaar AUGUST.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016:1 (First Edition)

2016 August Issue 1 Newsletter of the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences www.up.ac.za The med-fly, Ceratitis Capitata (Photo: Andre Coetzer). Read article on page 26. UP an integral part of the future of Africa “A space that will bring together 300 young, talented people who will time recognising the global repositioning of higher education at the live and work together and undertake doctoral research while taking cutting-edge of science.” a leadership journey. They will be a generation that will produce In 2010 UP began a process of long-term strategic planning which science for policy-making and policy implementation.” These words is in alignment with the current long-term strategy referred to as of Vice-Chancellor and Principal of the University of Pretoria (UP), UP 2025. In the process of developing this strategy, UP conducted Prof Cheryl de la Rey summarised the essence of Future Africa at the a number of environmental scans and, through these, a number of recent ground-breaking ceremony at the Future Africa Campus on trends were recognised that were likely to shape the future of the the University’s Experimental Farm. institution, science and scholarships. She explained: ”What we are talking about is a new model of doctoral The trend that significantly influenced UP’s strategy was the widely education that is coupled with leadership development, and an recognised realisation that the challenges and major problems endeavour to close the gap between natural and social sciences, and currently facing the world, and particularly Africa, can be resolved between universities, science and policy implementation.” through integrated approaches to science. -

Faculty of Health Sciences Prospectus 2021 Mthatha Campus

WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES PROSPECTUS 2021 MTHATHA CAMPUS @WalterSisuluUni Walter Sisulu University www.wsu.ac.za WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY MTHATHA CITY CAMPUS Prospectus 2021 Faculty of Health Sciences FHS Prospectus lpage i Walter Sisulu University - Make your dreams come true MTHATHA CAMPUS FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES PROSPECTUS 2021 …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… How to use this prospectus Note this prospectus contains material and information applicable to the whole campus. It also contains detailed information and specific requirements applicable to programmes that are offered by the campus. This prospectus should be read in conjunction with the General Prospectus which includes the University’s General Rules & Regulations, which is a valuable source of information. Students are encouraged to contact the Academic Head of the relevant campus if you are unsure of a rule or an interpretation. Disclaimer Although the information contained in this prospectus has been compiled as accurately as possible, WSU accepts no responsibility for any errors or omissions. WSU reserves the right to make any necessary alterations to this prospectus as and when the need may arise. This prospectus is published for the 2021 academic year. Offering of programmes and/or courses not guaranteed. Students should note that the offering of programmes and/or courses as described in this prospectus is not guaranteed and may be subject to change. The offering of programmes and/or courses is dependent on viable -

A Bibliography on Indians in South Africa : a Guide to Materials at the Documentation Centre

.A BIBLIOGRAPHY ON INDIANS IN SOUTH AFRICA : A GUIDE TO MATERIALS AT THE DOCUMENTATION CENTRE . A compiled by K CHETTY Documentation Centre Series, no 1 1990 University of Durban- Westville ISBN: 0-947445-02-1 INT ROD UCT 10M The FXblicatlon of this guide arises from a strong need to make known the nature and extent of the PUBLISHED AND UNPUBLISHED materials at the Docunentatlon Centre of the University of Durban-~estville on the subject 'The Indian In South Africa'. The Centre's materials Include books, manuscripts, theses, audio-visusl material, newspapers, serials and general archive material. This first bibliography In the Docunentation Centre Series concentrates on the variety of materials available UNDER EACH CLASSIFICATION end sorted by BRM (Blbl iographlc Record Nunber) - see Section A. Only entries of type "Manuscript" have been Isolated from the coq:xJterlsed records and this aCCOU'lts for the "missing" flUR)ers In the sequence of BRN's listed. The BRN Is a unique identifier for the record and this flUR)er Is most suited to serve as a LINK to sections (B-F). This link Is established by quoting only the BRN In these sections (B-F) so that this flUR)er can be used to POINT TO the FUll ENTRY In Section A. The ' linking' technique ~loyed has enabled the Inclusion of many indexes (Section B-G), which serve as cross references to the Primary Record Description (Section A), consisting of a title,. remarks, dates, sUllll8ry, classification nurber and the BRN. The Indexes included are as follows INDEX SECTION MAIN INDEX A TITLE INDEX -

PSM Public Sector Manager

UPCOMING EVENTS Human Rights Day World Water Day 21 March 22 March The national Human Rights Day celebra- Every year during March, the Department of tions this year will commence with a Water Affairs celebrates National Water Week in formal programme at the Walter Sisulu South Africa, which also features World Water Square in Kliptown, Soweto, where Pres- Day on 22 March. ident Jacob Zuma will deliver a keynote World Water Day grew out of the 1992 United address. Thereafter, the celebrations will Nations (UN) Conference on Environment and continue at Orlando Stadium, Soweto. Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro. The UN General Assembly designated 22 March of each year as the World Day for Water. The theme for this year’s campaign is: Water is life – respect it, conserve it, enjoy it. 13th Cape Town International Jazz Festival 30 – 31 March The Cape Town International Jazz Festi- val has grown into a hugely successful international event since its inception in 2000. Each year, more than 30 000 music lovers flock to this proudly South African music festival, which is ranked No 4 in the world, outshining events such as Switzerland's Montreaux Festival and the North Sea Jazz Festival in Netherlands. The festival’s winning formula of bringing more than 40 international and local artists to perform over two days on five stages has earned it the status of being the most prestigious event of its kind on the African conti- nent. Known as Africa's “grandest gath- ering”, the festival will be in its 13th year when it takes place at the Cape Town Freedom Day International Convention Centre. -

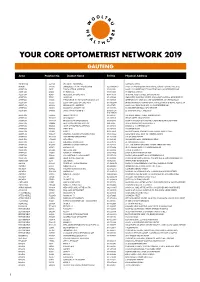

Your Core Optometrist Network 2019 Gauteng

YOUR CORE OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2019 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 9071046 SHOPS -

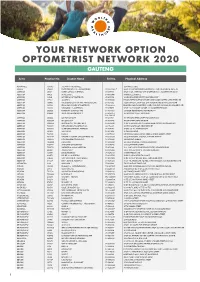

Your Network Option Optometrist Network 2020 Gauteng

YOUR NETWORK OPTION OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2020 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 -

CONICYT Ranking Por Disciplina > Sub-Área OECD (Académicas) Comisión Nacional De Investigación 1

CONICYT Ranking por Disciplina > Sub-área OECD (Académicas) Comisión Nacional de Investigación 1. Ciencias Naturales > 1.6 Ciencias Biológicas Científica y Tecnológica PAÍS INSTITUCIÓN RANKING PUNTAJE USA Harvard University 1 5,000 USA Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) 2 5,000 UNITED KINGDOM University of Oxford 3 5,000 USA Stanford University 4 5,000 UNITED KINGDOM University of Cambridge 5 5,000 USA Johns Hopkins University 6 5,000 USA University of California San Francisco 7 5,000 USA University of Washington Seattle 8 5,000 UNITED KINGDOM University College London 9 5,000 USA Cornell University 10 5,000 CANADA University of Toronto 11 5,000 USA University of Pennsylvania 12 5,000 USA University of California San Diego 13 5,000 DENMARK University of Copenhagen 14 5,000 USA University of Michigan 15 5,000 USA University of California Berkeley 16 5,000 USA University of California Los Angeles 17 5,000 USA Duke University 18 5,000 USA University of California Davis 19 5,000 UNITED KINGDOM Imperial College London 20 5,000 USA Columbia University 21 5,000 USA Yale University 22 5,000 USA University of Minnesota Twin Cities 23 5,000 FRANCE Universite Paris Saclay (ComUE) 24 5,000 USA University of North Carolina Chapel Hill 25 5,000 AUSTRALIA University of Queensland 26 5,000 AUSTRALIA University of Melbourne 27 5,000 USA Washington University (WUSTL) 28 5,000 NETHERLANDS Utrecht University 29 5,000 USA University of Wisconsin Madison 30 5,000 FRANCE Sorbonne Universite 31 5,000 SWEDEN Karolinska Institutet 32 5,000 USA University -

The City of Johannesburg Is One of South Africa's Seven Metropolitan Municipalities

NUMBER 26 / 2010 Urbanising Africa: The city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) By: Editors Authors: Alonso Ayala Peter Ahmad Ellen Geurts Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 1 Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) Authors: Peter Ahmad Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs Editors: Alonso Ayala Ellen Geurts IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 2 Introduction This working paper contains a selection of 7 articles written by participants in a Refresher Course organised by IHS in August 2010 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The title of the course was Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited - Ensuring liveable and sustainable inner-cities in Southern African countries: making it work for the poor. The course dealt in particular with inner-city revitalisation in Southern African countries, namely South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Inner-city revitalisation processes differ widely between the various cities and countries; e.g. in Lusaka and Mbabane few efforts have been undertaken, whereas Johannesburg in particular but also other South Africa cities have made major investments to revitalise their inner-cities. The definition of the inner-city also differs between countries; in Lusaka the CBD is synonymous with the inner-city, whereas in Johannesburg the inner-city is considered much larger than only the CBD. -

Walter Sisulu University General Prospectus 2020

WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY GENERAL PROSPECTUS 2020 General Rules and Regulations www.wsu.ac.za GENERAL PROSPECTUS 2020 This General Prospectus applies to all four campuses of Walter Sisulu University. LEGAL RULES 1. The University may in each year amend its rules. 2. The rules, including the amended rules, are indicated in the 2020 Prospectus. 3. The rules indicated in the 2020 Prospectus will apply to each student registered at Walter Sisulu University for 2020. 4. These rules will apply to each student, notwithstanding whether the student had first registered at the University prior to 2020. 5. When a student registers in 2020, the student accepts to be bound by the rules indicated in the 2020 prospectus. 6. The University may amend its rules after the General Prospectus has been printed. Should the University amend its rules during 2020, the amended rules will be communicated to students. Students will be bound by such amended rules. CAMPUSES & FACULTIES MTHATHA CAMPUS 1. Faculty of Commerce & Administration 2. Faculty of Educational Sciences 3. Faculty of Health Sciences 4. Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences & Law 5. Faculty of Natural Sciences BUTTERWORTH CAMPUS 1. Faculty of Education 2. Faculty of Engineering & Technology 3. Faculty of Management Sciences BUFFALO CITY CAMPUS 1. Faculty of Business Sciences 2. Faculty of Science, Engineering & Technology QUEENSTOWN CAMPUS 1. Faculty of Economics & Information Technology Systems 2. Faculty of Education & School Development 1 2020 PROSPECTUS ALL CORRESPONDENCE TO BE ADDRESSED TO: -

FORMATO PDF Ranking Instituciones Acadã©Micas Por Sub Ã

Ranking Instituciones Académicas por sub área OCDE 2020 3. Ciencias Médicas y de la Salud > 3.02 Medicina Clínica PAÍS INSTITUCIÓN RANKING PUNTAJE USA Harvard University 1 5,000 CANADA University of Toronto 2 5,000 USA Johns Hopkins University 3 5,000 USA University of Pennsylvania 4 5,000 USA University of California San Francisco 5 5,000 UNITED KINGDOM University College London 6 5,000 USA Duke University 7 5,000 USA Stanford University 8 5,000 USA University of California Los Angeles 9 5,000 USA University of Washington Seattle 10 5,000 USA Yale University 11 5,000 USA University of Pittsburgh 12 5,000 USA University of Michigan 13 5,000 AUSTRALIA University of Sydney 14 5,000 USA Columbia University 15 5,000 USA Washington University (WUSTL) 16 5,000 USA Emory University 17 5,000 UNITED KINGDOM Imperial College London 18 5,000 USA Northwestern University 19 5,000 USA University of California San Diego 20 5,000 USA Vanderbilt University 21 5,000 GERMANY Ruprecht Karls University Heidelberg 22 5,000 SWEDEN Karolinska Institutet 23 5,000 USA Cornell University 24 5,000 BELGIUM KU Leuven 25 5,000 UNITED KINGDOM University of Oxford 26 5,000 USA Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai 27 5,000 USA University of North Carolina Chapel Hill 28 5,000 FRANCE Sorbonne Universite 29 5,000 UNITED KINGDOM Kings College London 30 5,000 USA Ohio State University 31 5,000 FRANCE Universite Sorbonne Paris Cite-USPC (ComUE) 32 5,000 USA University of Colorado Health Science Center 33 5,000 SOUTH KOREA Seoul National University (SNU) 34 5,000 NETHERLANDS -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Chapter Introduction A prominent aspect of topical urban planning and development thought focuses on the need to valorise, acknowledge and adequately represent certain groups of people that have been marginalised in the contemporary metropolis (Sandercock, 1998; Sassen, 1996). These include ethnic minorities, immigrants, poor people, women and people with disabilities, amongst other groupings. It is argued that the recognition of these members of society is essential in terms of urban planning and governance, and in their servicing the corporate centre of the economy. This is indeed more important when considering that diversity continues to flourish in the world today even though economic globalisation appears to be on its way toward creating an integrated world market (Smith, 2003, 7). This diversity, originating from either an economic, social or political ethos, lends itself in large part to the presence of marginalised communities, such as ethnic minorities and immigrants, in cities around the world. Sandercock (1998, 164) aptly describes this scenario as follows: “Multi-ethnic, multi-racial and multi-national populations are becoming a dominant characteristic of cities and regions across the globe,…”. Most major, diverse cities around the world can thus be thought of as being cosmopolitan metropolises. Harrison (in Harrison et al (eds.), 2003, 22) states that within the postmodernist framework, fragmentation becomes diversity and is something to be celebrated rather than conquered, and that it is not an evil. However, if viewed otherwise, fragmentation has strong negative connotations, hence creating the potential for conflict with the presence of diversity. Whatever the discourse, diversity is important in planning, either as something to defend or as a valuable resource to make use of. -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature