The Ghaznavid Marble Architectural Decoration: an Overview.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Statistical Bulletin 2013 Annual Statistical Bulletin

2013 OPEC OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin 2013 Annual Statistical Bulletin OPEC Helferstorferstrasse 17, A-1010 Vienna, Austria Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries www.opec.org Team for the preparation of the OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin 2013 Director, Research Division Editorial Team Omar Abdul-Hamid Head, Public Relations and Information Department Project Leader Angela Agoawike Head, Data Services Department Adedapo Odulaja Editor Alvino-Mario Fantini Coordinator Ramadan Janan Design and Production Coordinator Alaa Al-Saigh Statistics Team Pantelis Christodoulides, Hannes Windholz, Senior Production Assistant Mouhamad Moudassir, Klaus Stöger, Harvir Kalirai, Diana Lavnick Mohammad Sattar, Ksenia Gutman Web and CD Application Dietmar Rudari, Zairul Arifin Questions on data Although comments are welcome, OPEC regrets that it is unable to answer all enquiries concerning the data in the ASB. Data queries: [email protected]. Advertising The OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin now accepts advertising. For details, please contact the Head, PR and Information Department at the following address: Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Helferstorferstrasse 17, A-1010 Vienna, Austria Tel: +43 1 211 12/0 Fax: +43 1 216 43 20 PR & Information Department fax: +43 1 21112/5081 Advertising: [email protected] Website: www.opec.org Photographs Page 5: Diana Golpashin. Pages 7, 13, 21, 63, 81, 93: Shutterstock. © 2013 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries ISSN 0475-0608 Contents Foreword 5 Tables Page Section 1: -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

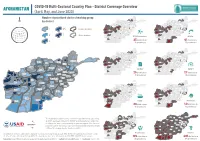

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Finding the Patterns of Indian Mosques Architecture

Vol.14/ No.48/ Jun 2017 Received 2017/03/04 Accepted 2017/05/15 Persian translation of this paper entitled: الگویابی معماری مساجد هند is also published in this issue of journal. Finding the Patterns of Indian Mosques Architecture Ehsan Dizany* Abstract India is one of the countries that has had diverse civilizations from the distant past, so in architectural standpoint, this country is rich and varied. The arrival of Islam in India and the formation of Islamic governments led to the formation of a certain type of Islamic architecture in this subcontinent. The architecture of Indian mosques is evaluated as a prominent model of Islamic architecture of subcontinent. This study is based on the assumption that the pattern of Indian mosques architecture is a combination of early Iranian-Islamic architecture of mosques and Indian vernacular architecture. Finding the roots of Architectural features of Indian mosques is the subject of this article. In this paper, the influence of early Islamic mosques’ architecture and rich and historical architecture of India on Indian mosques architecture before the arrival of Islam and the architecture of developed Islamic civilizations in the Indian neighborhoods such as Iran, is studied. Generally Indian mosques architectural features include prayer-hall in the Qibla direction, existence of courtyard, Four-Iwan pattern, crusts odd divisions, especially triple ones, presence of mosque in plaza and its position on a Soffeh (in height), access to the mosque entrances by wide stairs, triple divisions of Gonbad Khane in the Qibla direction and the use of transparent porticos around courtyard (Half of the outer crust that has external view). -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Afghanistan Ghazni Province Land Cover

W # AFGHANISTAN E C Sar-e K har Dew#lak A N # GHAZNI PROVINCE Qarah Qowl( 1) I Qarkh Kamarak # # # # # Regak # # Gowshak # # # Qarah Qowl( 2) R V Qada # # # # # # Bandsang # # Dopushta Panqash # # # # # # # Qashkoh Kholaqol # LAND COVER MAP # Faqir an O # Sang Qowl Rahim Dad # # Diktur (1) # Owr Mordah Dahane Barikak D # Barigah # # # Sare Jiska # Baday # # Kheyr Khaneh # Uchak # R # Jandad # # # # # # # # # # Shakhalkhar Zardargin Bumak # # Takhuni # # # # # # # Karez Nazar # Ambolagh # # # # # # Barikak # # Hesar # # # # # Yarum # # # A P # # # # # # Kataqal'a Kormurda # # # # Qeshlaqha Riga Jusha Tar Bulagh # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # Ahangari # # Kuz Foladay # Minqol # # # Syahreg (2) # # # Maqa # Sanginak # # Baghalak # # # # # # # # # Sangband # Orka B aba # Godowl # Nayak # # # Gadagak # # # # Kota Khwab Altan # # Bahram # # # Katar # # # Barik # Qafak # Qargatak # # # # # # Garmak (3) # # # # # # # # # # Ternawa # # # Kadul # # # # Ghwach # K # # Ata # # # Dandab # # # # # Qole Khugan Sewak (2) Sorkh Dival # # # # # # # # Qabzar (2) # # Bandali # Ajar # Shebar # Hajegak # Sawzsang Podina N ## # # Churka # Nala # # # # # # # Qabzar-1 Turgha # Tughni # Warzang Sultani # # # # # # # # # # # # # Ramzi Qureh Now Juy Negah # # # # # # # # Shew Qowl # Syahsangak A # # # # # # # O # Diktur (2) # Kajak # # Mar Bolagh R V # Ajeda # Gola Karizak # # # Navor Sham # # Dahane Yakhshi Kolukh P # # # # AIMS Y Tanakhak Qal'a-i Dasht I Qole Aymad # Kotal Olsenak Mianah Bed # # # # N Tarbolagh Mar qolak Minqolak Sare Bed Sare Kor ya Ta`ina -

Local Perspectives on Peace and Elections Ghazni Province, South-Eastern Afghanistan

Local perspectives on peace and elections Ghazni Province, south-eastern Afghanistan Interviews conducted by Abdul Hadi Sadat, a researcher with Unit (AREU), the Center for Policy and Human Development over 15 years of experience in qualitative social research with (CPHD) and Creative Associates International. He has a degree organisations including the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation injournalism from Kabul University. ABSTRACT The following statements are taken from longer their views on elections, peace and reconciliation. interviews with community members across two Respondents’ ages and ethnic groups vary, as do their different rural districts in Ghazni Province in south- levels of literacy. Data were collected by Abdul Hadi eastern Afghanistan between November 2017 and Sadat as part of a larger research project funded by the March 2018. Interviewees were asked questions about UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Female NGO employee I think the international organisations’ involvement is very Government officials and the IEC [Independent Election vital and they have an important role in elections, but I Commission] are not capable of talking with the Taliban don’t think they will have an important role in reconciliation regarding the election, but community representatives can with the Taliban because they themselves do not want convince them not to do anything to disrupt the election and Afghanistan to be in peace. If they wanted this we would even encourage them to participate in the election process. have better life. They have the power to force the Taliban to reconcile with Afghanistan government. Female youth, unemployed I don’t know for sure whether the Taliban will allow elections Male village elder to take place here or not, but in those villages where the For decades we have been experiencing war so all people security is low the Taliban will not let the people go to the are very tired with fighting, killing and bombing. -

Kerman Province

In TheGod Name of Kerman Ganjali khan water reservoir / Contents: Subject page Kerman Province/11 Mount Hezar / 11 Mount joopar/11 Kerman city / 11 Ganjalikhan square / 11 Ganjalikhan bazaar/11 Ganjalikhan public bath /12 Ganjalikhan Mint house/12 Ganjalikhan School/12 Ganjalikhan Mosque /13 Ganjalikhan Cross market place /13 Alimardan Khan water reservoir /13 Ibrahimkhan complex/ 13 Ibrahimkhan Bazaar/14 Ibrahimkhan School /14 Ibrahimkhan bath/14 Vakil Complex/14 Vakil public bath / 14 Vakil Bazaar / 16 Vakil Caravansary / 16 Hajagha Ali complex / 16 Hajagha Ali mosque / 17 Hajagha Ali bazaar / 17 Hajagha Ali reservoir / 17 Bazaar Complex / 17 Arg- Square bazaar / 18 Kerman Throughout bazaar / 18 North Copper Smithing bazaar / 18 Arg bazaar / 18 West coppersmithing bazaar / 18 Ekhteyari bazaar / 18 Mozaffari bazaar / 19 Indian Caravansary / 19 Golshan house / 19 Mozaffari grand mosque / 19 Imam mosque / 20 Moshtaghieh / 20 Green Dome / 20 Jebalieh Dome / 21 Shah Namatollah threshold / 21 Khaje Etabak tomb / 23 Imam zadeh shahzadeh Hossien tomb / 23 Imam zadeh shahzadeh Mohammad / 23 Qaleh Dokhtar / 23 Kerman fire temple / 24 Moaidi Ice house / 24 Kerman national library / 25 Gholibig throne palace / 25 Fathabad Garden / 25 Shotor Galoo / 25 Shah zadeh garden / 26 Harandi garden / 26 Arg-e Rayen / 26 Ganjalikhan anthropology museum / 27 Coin museum / 27 Harandi museum garden / 27 Sanatti museum / 28 Zoroasterian museum / 28 Shahid Bahonar museum / 28 Holy defense museum / 28 Jebalieh museum / 29 Shah Namatollah dome museum / 29 Ghaem wooden -

Life Science Journal 2013;10(9S) Http

Life Science Journal 2013;10(9s) http://www.lifesciencesite.com Studying Mistaken Theory of Calendar Function of Iran’s Cross-Vaults Ali Salehipour Department of Architecture, Heris Branch, Islamic Azad University, Heris, Iran [email protected] Abstract: After presenting the theory of calendar function of Iran’s cross-vaults especially “Niasar” cross-vault in recent years, there has been lots of doubts and uncertainty about this theory by astrologists and archaeologists. According to this theory “Niasar cross-vault and other cross-vaults of Iran has calendar function and are constructed in a way that sunrise and sunset can be seen from one of its openings in the beginning and middle of each season of year”. But, mentioning historical documentaries we conclude here that the theory of calendar function of Iran’s cross-vaults does not have any strong basis and individual cross-vaults had only religious function in Iran. [Ali Salehipour. Studying Mistaken Theory of Calendar Function of Iran’s Cross-Vaults. Life Sci J 2013;10(9s):17-29] (ISSN:1097-8135). http://www.lifesciencesite.com. 3 Keywords: cross-vault; fire temple; Calendar function; Sassanid period 1. Introduction 2.3 Conformity Of Cross-Vaults’ Proportions With The theory of “calendar function of Iran’s Inclined Angle Of Sun cross-vaults” is a wrong theory introduced by some The proportion of “base width” to “length of interested in astronomy in recent years and this has each side” of cross-vault, which is a fixed proportion caused some doubts and uncertainties among of 1 to 2.3 to 3.9 makes 23.5 degree arch between researchers of astronomy and archaeologists but the edges of bases and the visual line created of it except some distracted ideas, there has not been any which is equal to inclining edge of sun. -

Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Urban Studies Senior Seminar Papers Urban Studies Program 11-2009 Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan Benjamin Dubow University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar Dubow, Benjamin, "Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan" (2009). Urban Studies Senior Seminar Papers. 13. https://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar/13 Suggested Citation: Benjamin Dubow. "Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan." University of Pennsylvania, Urban Studies Program. 2009. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar/13 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan Abstract The 2004 election was a disaster. For all the unity that could have come from 2001, the election results shattered any hope that the country had overcome its fractures. The winner needed to find a way to unite a country that could not be more divided. In Afghanistan’s Panjshir Province, runner-up Yunis Qanooni received 95.0% of the vote. In Paktia Province, incumbent Hamid Karzai received 95.9%. Those were only two of the seven provinces where more than 90% or more of the vote went to a single candidate. Two minor candidates who received less than a tenth of the total won 83% and 78% of the vote in their home provinces. For comparison, the most lopsided state in the 2004 United States was Wyoming, with 69% of the vote going to Bush. This means Wyoming voters were 1.8 times as likely to vote for Bush as were Massachusetts voters. Paktia voters were 120 times as likely to vote for Karzai as were Panjshir voters. -

Culture and Tourism

IRAN STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 1391 17. CULTURE AND TOURISM organization called ''Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization", the related data have been Introduction provided by the new organization. Data on pilgrims include only those dispatched by Hajj and Pilgrimage Organization. Definitions and concepts his chapter presents statistical information Production of radio and television on radio and television programmes, programmes:is a process in which the contextual Tpress, books and public libraries, cinemas, (massage) and structural componentsof the museums, monuments, touristsarrived and massage are incorporated artistically and pilgrims. Following paragraphs summarize the technically using required resources in order to be history of data collection in these areas. broadcast on TV, radio and the Internet. Regular data compilation on radio and television Radio and television broadcasting: refers to a programmes and museums began in the years produced and broadcast programme which can be 1345 and 1347 respectively. received by people on radio, TV and the Internet. The earliest data on movies available in the SCI National production and broadcast of date back to the year 1348. They were produced programme: refers to the programme produced by the Culture and Art Ministry, renamed the and broadcast for people in the country. Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance after International production and broadcast of the victory of the Islamic Revolution. programme: refers to the programme produced Comprehensive data collection on the press was and broadcast for overseas people. first accomplished by the SCI under the title of Radio and television network: is an "Review of the country’s publications survey" in organizational structure responsible for activities the year 1349. -

Jalalabad & Eastern Afghanistan

© Lonely Planet Publications 181 EASTERN AFGHANISTAN Jalalabad & JALALABAD & Eastern Afghanistan ﺟﻼل ﺑﺎد و ﺷﺮق اﻓﻐﺎﻧﺴﺘﺎن Think of the great clichés of the Afghan character and you’ll be transported to Afghani- stan’s rugged east. Tales of honour, hospitality and revenge abound here, as hardy fighters defend the lonely mountain passes that lead to the Indian subcontinent. For Afghan, read Pashtun: the dominant ethnic group in the east whose tribal links spill across the border deep into Pakistan. Jalalabad is the region’s most important city. Founded by the Mughals as a winter retreat, it sits in an area with links back to when Afghanistan was a Buddhist country and a place of monasteries, pilgrims and prayer wheels. Sweltering in summer, you can quench your thirst with a mango juice before heading for the cooler climes of the Kabul Plateau, via the jaw-dropping Tangi Gharu Gorge. A stone’s throw from Jalalabad is the Khyber Pass, the age-old gateway to the Indian subcontinent. Getting your passport stamped here as you slip between Afghanistan and Pakistan is to experience one of Asia’s most evocative border crossings. If you’ve been in Afghanistan a while, you might find the sudden Pakistani insistence on providing you with an armed guard for your onward journey a little bemusing. Sadly much of the east remains out of bounds to travellers. The failures of post- conflict reconstruction have allowed an Islamist insurgency to smoulder among the peaks and valleys that dominate this part of the country. The beautiful woods and slopes of Nuristan – long a travellers’ grail – remain as distant a goal as ever and the current climate means that carefully checking security issues remains paramount before any trip to the region.