Service Delivery in Taliban Influenced Areas…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress in Afghanistan Bucharest Summit2-4 April 2008 Progress in Afghanistan

© MOD NL © MOD Canada © MOD Canada Progress in Afghanistan Progress in Bucharest Summit 2-4 April 2008 Bucharest Summit2-4 Progress in Afghanistan Contents page 1. Foreword by Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy, ..........................1 Jean-François Bureau, and NATO Spokesman, James Appathurai 2. Executive summary .........................................................................................................................................2 3. Security ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 • IED attacks and Counter-IED efforts 4 • Musa Qala 5 • Operations Medusa successes - Highlights Panjwayi and Zhari 6 • Afghan National Army 8 • Afghan National Police 10 • ISAF growth 10 4. Reconstruction and Development ............................................................................................... 12 • Snapshots of PRT activities 14 • Afghanistan’s aviation sector: taking off 16 • NATO-Japan Grant Assistance for Grassroots Projects 17 • ISAF Post-Operations Humanitarian Relief Fund 18 • Humanitarian Assistance - Winterisation 18 5. Governance ....................................................................................................................................................... 19 • Counter-Narcotics 20 © MOD Canada Foreword The NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission is approaching five years of operations in Afghanistan. This report is a -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy

Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy July 18, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45818 SUMMARY R45818 Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy July 18, 2019 Afghanistan has been a significant U.S. foreign policy concern since 2001, when the United States, in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led a military Clayton Thomas campaign against Al Qaeda and the Taliban government that harbored and supported it. Analyst in Middle Eastern In the intervening 18 years, the United States has suffered approximately 2,400 military Affairs fatalities in Afghanistan, with the cost of military operations reaching nearly $750 billion. Congress has appropriated approximately $133 billion for reconstruction. In that time, an elected Afghan government has replaced the Taliban, and most measures of human development have improved, although Afghanistan’s future prospects remain mixed in light of the country’s ongoing violent conflict and political contention. Topics covered in this report include: Security dynamics. U.S. and Afghan forces, along with international partners, combat a Taliban insurgency that is, by many measures, in a stronger military position now than at any point since 2001. Many observers assess that a full-scale U.S. withdrawal would lead to the collapse of the Afghan government and perhaps even the reestablishment of Taliban control over most of the country. Taliban insurgents operate alongside, and in periodic competition with, an array of other armed groups, including regional affiliates of Al Qaeda (a longtime Taliban ally) and the Islamic State (a Taliban foe and increasing focus of U.S. policy). U.S. -

Taliban Fragmentation FACT, FICTION, and FUTURE by Andrew Watkins

PEACEWORKS Taliban Fragmentation FACT, FICTION, AND FUTURE By Andrew Watkins NO. 160 | MARCH 2020 Making Peace Possible NO. 160 | MARCH 2020 ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines the phenomenon of insurgent fragmentation within Afghanistan’s Tali- ban and implications for the Afghan peace process. This study, which the author undertook PEACE PROCESSES as an independent researcher supported by the Asia Center at the US Institute of Peace, is based on a survey of the academic literature on insurgency, civil war, and negotiated peace, as well as on interviews the author conducted in Afghanistan in 2019 and 2020. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Andrew Watkins has worked in more than ten provinces of Afghanistan, most recently as a political affairs officer with the United Nations. He has also worked as an indepen- dent researcher, a conflict analyst and adviser to the humanitarian community, and a liaison based with Afghan security forces. Cover photo: A soldier walks among a group of alleged Taliban fighters at a National Directorate of Security facility in Faizabad in September 2019. The status of prisoners will be a critical issue in future negotiations with the Taliban. (Photo by Jim Huylebroek/New York Times) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2020 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

(SIKA) – East Final Report

Stability in Key Areas (SIKA) – East Final Report ACKU 2 ACKU Ghazni Province_Khwaja Umari District_Qala Naw Girls School Sport Field (PLAY) opening ceremony ii Stability in Key Areas (SIKA) – East Final Report ACKU The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government iii Name of USAID Activity: Afghanistan Stability in Key Areas (SIKA) - East Name of Prime Contractor: AECOM International Development $144,948,162.00 Total funding: Start date: December 7, 2011 Option period: December 3, 2013 End date: September 6, 2015 Geographic locations: Ghazni Province: Andar, Bahrami Shahid, Dih Yak, Khwaja Umari, Qarabagh, and Muqur Khost Province: Gurbuz, Jaji Maidan, Mando Zayi, Tani, and Nadir Shah Kot Logar Province: Baraki Barak, Khoshi, and Mohammad Agha Maydan Wardak Province: Chaki Wardak, Jalrez, Nirkh, Saydabad and Maydan Shahr Paktya Province: Ahmad Abad, Laja Ahmad Khail, Laja Mangal, Zadran, Garda Serai, Zurmat, Ali Khail, Mirzaka, and Sayed Karam Paktika Province: Sharan and Yosuf Khel Overall goals and objectives: SIKA – East promotes stabilization in key areas by supporting GIRoA at the district level, while coordinating efforts at the provincial level to implement community led development and governance initiatives that respond to the population’s needs and concerns to build confidence, promote stability, and increase the provision of basic services. • Address Instability and Respond to Concerns: Provincial and District Entities increasingly address Expected Results: sources of instability and take measures to respond to the population’s development and governance concerns. • Enable Access to Services: Provincial and District entities understand what organizations and provincial line departments work within their geographic areas, ACKUwhat kind of services they provide, and how the population can access those services. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

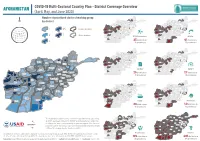

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

1 USIP –ADST Afghan Experience Project Interviwe #1 Executive

USIP –ADST Afghan Experience Project Interviwe #1 Executive Summary The interviewee is a Farsi speaker and retired FSO who has had prior Afghan experience, including working with refugees during the period the Taliban was fighting to take over the country in 1995. He returned to Kabul in 2002 as chief of the political section, although retired, for seven months. He returned in 2003 and worked at the U.S. civil affairs mission in Herat for 6 months. He came back later in 2003 to Afghanistan working for the Asia Foundation. He worked on a PRT for approximately three months in late 2004 in Herat. The American presence was minimal when he got there. Security was excellent and the local warlord, Ismael Khan, was using revenues he siphoned from customs houses into development projects. Shortly after subject arrived in Herat, Khan was ousted in a brief battle by forces loyal to Kabul and with the threat of unrest U.S. forces were increased in the area. Our subject suggested to Khan that he make peace with the Kabul government, and he did, perhaps in part on the advice of subject. The Herat PRT had about one hundred American uniformed troops with three civilians, State, AID, Agriculture. Subject was the political advisor to the civil affairs staff, a reserve unit from Minnesota. But much of their work was soon taken over or undercut by the U.S. military task force commander brought in in response to the ouster of Khan. According to subject, the task force commander in the region saw himself as the political expert. -

“Poppy Free” Provinces: a Measure Or a Target?

Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Case Study Series WATER MANAGEMENT, LIVESTOCK AND THE OPIUM ECONOMY “Poppy Free” Provinces: A Measure or a Target? This report is one of seven multi-site case studies undertaken during the second stage of AREU’s three-year study “Applied Thematic Research into Water Management, Livestock and the Opium Economy” (WOL). David Mansfield Funding for this research was provided by the European Commission. May 2009 Editor: Emily Winterbotham Layout: AREU Publications Team © 2009 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] or by calling (+93)(0)799 608 548. “Poppy Free” Provinces: A Measure or a Target? About the Author David Mansfield is a specialist on development in drugs-producing environments. He has spent 17 years working in coca- and opium-producing countries, with over ten years experience conducting research into the role of opium in rural livelihood strategies in Afghanistan. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation based in Kabul. AREU’s mission is to conduct high-quality research that informs and influences policy and practice. AREU also actively promotes a culture of research and learning by strengthening analytical capacity in Afghanistan and facilitating reflection and debate. Fundamental to AREU’s vision is that its work should improve Afghan lives. -

Special Report on Kunduz Province

AFGHANISTAN HUMAN RIGHTS AND PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT SPECIAL REPORT ON KUNDUZ PROVINCE © 2015/Xinhua United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan December 2015 AFGHANISTAN HUMAN RIGHTS AND PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT SPECIAL REPORT ON KUNDUZ PROVINCE United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan December 2015 Photo on Front Cover © 2015/ Jawed Omid/Xinhua. A man searches for the bodies of his relatives inside the ruins of the Médecins Sans Frontières hospital in Kunduz city. (On 3 October, a United States AC-130 aircraft carried out a series of airstrikes against the hospital, resulting in at least 30 deaths and 37 injured). Photo taken on 11 October 2015. "Citizens of Kunduz were subjected to a horrifying ordeal. The street by street fighting coupled with a breakdown of the rule of law created an environment where civilians were subjected to shooting, other forms of violence, abductions, denial of medical care and restrictions of movement out of the city.” Nicholas Haysom, United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary-General in Afghanistan, Kabul, 25 October 2015. “This event was utterly tragic, inexcusable, and possibly even criminal. International and Afghan military planners have an obligation to respect and protect civilians at all times, and medical facilities and personnel are the object of a special protection. These obligations apply no matter whose air force is involved, and irrespective of the location." United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, Geneva, 3 October 2015, public statement about attack against the Médecins Sans Frontières hospital. -

Leveraging the Taliban's Quest for International Recognition

Leveraging the Taliban’s Quest for International Recognition Afghan Peace Process Issues Paper March 2021 By Barnett R. Rubin Summary: As the United States tries to orchestrate a political settlement in conjunction with its eventual military withdrawal from Afghanistan, it has overestimated the role of military pressure or presence and underestimated the leverage that the Taliban’s quest for sanctions relief, recognition and international assistance provides. As the U.S. government decides on how and when to withdraw its troops, it and other international powers retain control over some of the Taliban’s main objectives — the removal of both bilateral and United Nations Security Council sanctions and, eventually, recognition of and assistance to an Afghan government that includes the Taliban. Making the most of this leverage will require coordination with the Security Council and with Afghanistan’s key neighbors, including Security Council members China, Russia and India, as well as Pakistan and Iran. In April 2017, in a meeting with an interagency team on board a military aircraft en route to Afghanistan, U.S. President Donald J. Trump’s new national security advisor, retired Army Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, dismissed the ongoing effort to negotiate a settlement with the Taliban: “The first step, the national security adviser said, was to turn around the trajectory of the conflict. The United States had to stop the Taliban’s advance on the battlefield and force them to agree to concessions in the process .... US talks with the Taliban would only succeed when the United States returned to a position of strength on the battlefield and was ‘winning’ against the insurgency.”1 1 Donati, Jessica.