Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar M AY 2014 Above: Behsud Bridge, Nangarhar Province (Photo by TLO) A TLO M A P P I N G R EPORT Justice and Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar May 2014 In Cooperation with: © 2014, The Liaison Office. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, The Liaison Office. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] ii Acknowledgements This report was commissioned from The Liaison Office (TLO) by Cordaid’s Security and Justice Business Unit. Research was conducted via cooperation between the Afghan Women’s Resource Centre (AWRC) and TLO, under the supervision and lead of the latter. Cordaid was involved in the development of the research tools and also conducted capacity building by providing trainings to the researchers on the research methodology. While TLO makes all efforts to review and verify field data prior to publication, some factual inaccuracies may still remain. TLO and AWRC are solely responsible for possible inaccuracies in the information presented. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The Liaison Office (TL0) The Liaison Office (TLO) is an independent Afghan non-governmental organization established in 2003 seeking to improve local governance, stability and security through systematic and institutionalized engagement with customary structures, local communities, and civil society groups. -

Sunday, 06 October 2019 Venue: FAO Meeting Room Draft Agenda

Time: 14:00 – 15:30 hrs Date: Sunday, 06 October 2019 Venue: FAO Meeting Room Draft Agenda: Introduction of ANDMA Nangarhar Newly appointed Director Update on the current humanitarian situation in Nurgal (Kunar) and Surkhrod (Nangarhar) – DoRR, OCHA Petition from Surkhrod for Tents and IDPs left of assessment Update on the status of Joint Needs Assessment & Response – OCHA and Partners Petitions for IDPs from Laghman AOB www.unocha.org The mission of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is to mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. Coordination Saves Lives Update on Assessment & Response on Natural disasters – as of 21 April 2019 - IOM & ANDMA Deaths In Responde Province Districts Affected & Initial Info. # of Families Agencies Agencies Response Assistance Action Points j Status Assessed Families ured Assessed Assessed Responde Provided Affected d d Nangarhar 250 (1817 9 5 250 and 105 IOM, IMC, IOM, Ongoing NFI, Tents, -Health MHT will be deployed Assessment individuals) Assessment ongoing WFP, SCI, effective 23 April 2019.4.22, completed in Lalpur, NCRO, Pending: food, Kama, Rodat, Behsud, OXFAM, -WASH cluster will reassess the Jalalabad city, Goshta, RRD, ARCS, needs and respond accordingly. Mohmandara, Kot, Bati DACAAR, Kot DAIL, DA -IOM to share the list of families recommended for permanent Assessment ongoing: shelter with ACTED. Shirzad, Dehbala, Pachir- Agam, -ANDMA will clarify the land Chaparhar, -

Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Afghanistan’S Faryab Province Geert Gompelman ©2010 Feinstein International Center

JANUARY 2011 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship between Aid and Security in Afghanistan’s Faryab Province Geert Gompelman ©2010 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu Author Geert Gompelman (MSc.) is a graduate in Development Studies from the Centre for International Development Issues Nijmegen (CIDIN) at Radboud University Nijmegen (Netherlands). He has worked as a development practitioner and research consultant in Afghanistan since 2007. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank his research colleagues Ahmad Hakeem (“Shajay”) and Kanishka Haya for their assistance and insights as well as companionship in the field. Gratitude is also due to Antonio Giustozzi, Arne Strand, Petter Bauck, and Hans Dieset for their substantive comments and suggestions on a draft version. The author is indebted to Mervyn Patterson for his significant contribution to the historical and background sections. Thanks go to Joyce Maxwell for her editorial guidance and for helping to clarify unclear passages and to Bridget Snow for her efficient and patient work on the production of the final document. -

UNICEF Afghanistan Country Office Gender and COVID-19 Strategies

Putting women and girls at the forefront of UNICEF Afghanistan Programme: Gender and COVID-19 Update December 2020 /2020/Omid Fazel /2020/Omid UNICEF Afghanistan UNICEF © Background The COVID-19 pandemic has created a global crisis on an unprecedented scale, affecting lives and communities worldwide. As a result of the circumstances brought on by COVID-19, children, adolescent girls and women face a myriad challenges. These range from an increased exposure to violence and early marriage, to significant loss of learning opportunities, diminished access to health facilities and devastating economic losses. Within this context, the unique needs of women and girls have not been adequately prioritized in response plans. In addition, information about women and girls’ experiences often remains hidden within existing data, obscuring the complexity, nuances and uniqueness of their situation. In Afghanistan, the COVID-19 crisis has aggravated pre-existing gender inequalities that hamper women’s access to services. For example, women’s access to health and gender-based violence (GBV) services has been decimated, and 67 percent of women cannot go to health centers without a male escort (Care International 2020). This is also confirmed by a recent Oxfam Study in Afghanistan. This report presents the second and last gender newsletter for the year 2020 in Afghanistan Country Office (ACO). The newsletter captures promising programme strategies that were developed and put to scale during the pandemic to address the unique needs of mainly women and adolescent girls. Key Strategies by ACO to Address Gender Issues Affecting Women and Girls in Afghanistan Promising Strategy#1: Engagement of women CSOs into gender COVID-19 responses Lack of access to information on COVID-19 by specific civil society organizations (CSOs), Voice of Women, social groups, such as women and girls, was highlighted Women Activities & Social Services Association as a critical issue affecting access to COVID-19 related (WASSA), and Action Aid Afghanistan (AAA). -

Positive Deviance Research Report Jan2014

FutureGenerations Afghanistan . empowering communities to shape their futures ________________________________________________________________________________ Research Report Engaging Community Resilience for Security, Development and Peace building in Afghanistan ________________________________________________________________________________ December 2013 Funding Agencies United State Institute of Peace Rockefeller Brothers Fund Carnegie Corporation of New York Contact House # 115, 2nd Str., Parwan-2, Kabul, Afghanistan Cell: +93 (0) 799 686 618 / +93 (0) 707 270 778 Email: [email protected] Website: www.future.org 1 Engaging Community Resilience for Security, Development and Peacebuilding in Afghanistan Project Research Report Table of Contents List of Table List of Figures and Maps List of Abbreviations Glossary of local Language Words Chapter Title Page INTRODUCTION 3 Positive Deviance Process Conceptual Framework 4 • Phase-1: Inception • Phase-2: Positive Deviance Inquiry • Phase-3: Evaluation SECTION-1: Inception Phase Report 7 Chapter One POSITIVE DEVIANCE HISTORY AND DEFINITIONS 7 History 7 Definitions (PD concept, PD approach, PD inquiry, PD process, PD 8 methodology) a) Assessment Phase: Define, Determine, Discover 8 b) Application Phase: Design, Discern, Disseminate 9 Positive Deviance Principles 10 When to use positive deviance 10 Chapter Two RESEARCH CONTEXT 11 Challenges 11 Study Objectives 12 Site Selection 13 Research Methods 13 Composite Variables and Data Analysis 14 Scope and Limitation 15 Chapter Three SOCIO-POLITICAL -

The Informal Regulation of the Onion Market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About Us

Researching livelihoods and Afghanistan services affected by conflict Kabul Jalalabad The social life of the Nangarhar Pakistan onion: the informal regulation of the onion market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people make a living, educate their children, deal with illness and access other basic services in conflict-affected situations. Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals and international efforts at peace- building and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one- year inception phase: . State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations . State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations . Livelihood trajectories and economic activity under conflict The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), Focus1000 in Sierra Leone, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), -

“Poppy Free” Provinces: a Measure Or a Target?

Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Case Study Series WATER MANAGEMENT, LIVESTOCK AND THE OPIUM ECONOMY “Poppy Free” Provinces: A Measure or a Target? This report is one of seven multi-site case studies undertaken during the second stage of AREU’s three-year study “Applied Thematic Research into Water Management, Livestock and the Opium Economy” (WOL). David Mansfield Funding for this research was provided by the European Commission. May 2009 Editor: Emily Winterbotham Layout: AREU Publications Team © 2009 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] or by calling (+93)(0)799 608 548. “Poppy Free” Provinces: A Measure or a Target? About the Author David Mansfield is a specialist on development in drugs-producing environments. He has spent 17 years working in coca- and opium-producing countries, with over ten years experience conducting research into the role of opium in rural livelihood strategies in Afghanistan. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation based in Kabul. AREU’s mission is to conduct high-quality research that informs and influences policy and practice. AREU also actively promotes a culture of research and learning by strengthening analytical capacity in Afghanistan and facilitating reflection and debate. Fundamental to AREU’s vision is that its work should improve Afghan lives. -

Community- Based Needs Assessment

COMMUNITY- BASED NEEDS ASSESSMENT SUMMARY RESULTS PILOT ▪ KABUL As more IDPs and returnees urbanize and flock to cities, like Kabul, in search of livelihoods and security, it puts a strain on already overstretched resources. Water levels in Kabul have dramatically decreased, MAY – JUN 2018 forcing people to wait for hours each day to gather drinking water. © IOM 2018 ABOUT DTM The Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) is a system that HIGHLIGHTS tracks and monitors displacement and population mobility. It is districts assessed designed to regularly and systematically capture, process and 9 disseminate information to provide a better understanding of 201settlements with largest IDP and return the movements and evolving needs of displaced populations, populations assessed whether on site or en route. 828 In coordination with the Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation key informants interviewed (MoRR), in May through June 2018, DTM in Afghanistan piloted a Community-Based Needs Assessment (CBNA), intended as an 1,744,347 integral component of DTM's Baseline Mobility Assessment to individuals reside in the assessed settlements provide a more comprehensive view of multi-sectoral needs in settlements hosting IDPs and returnees. DTM conducted 117,023 the CBNA pilot at the settlement level, prioritizing settlements residents are returnees from abroad hosting the largest numbers of returnees and IDPs, in seven target 111,700 provinces of highest displacement and return, as determined by IDPs currently in host communities the round 5 Baseline Mobility Assessments results completed in mid-May 2018. DTM’s field enumerators administered the inter- 6,748 sectoral needs survey primarily through community focus group residents fled as IDPs discussions with key informants, knowledgeable about the living conditions, economic situation, access to multi-sectoral 21,290 services, security and safety, and food and nutrition, among residents are former IDPs who returned home other subjects. -

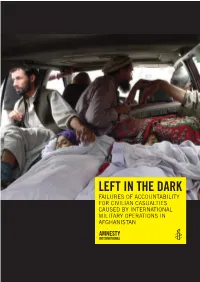

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Annex to Financial Sanctions: Afghanistan 01.02.21

ANNEX TO NOTICE FINANCIAL SANCTIONS: AFGHANISTAN THE AFGHANISTAN (SANCTIONS) (EU EXIT) REGULATIONS 2020 (S.I. 2020/948) AMENDMENTS Deleted information appears in strikethrough. Additional information appears in italics and is underlined. Individuals 1. ABBASIN, Abdul Aziz DOB: --/--/1969. POB: Sheykhan village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan a.k.a: MAHSUD, Abdul Aziz Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref): AFG0121 (UN Ref): TAi.155 (Further Identifying Information): Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for nonAfghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here. Listed On: 21/10/2011 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 01/02/2021 Group ID: 12156. 2. ABDUL AHAD, Azizirahman Title: Mr DOB: --/--/1972. POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Nationality: Afghan National Identification no: 44323 (Afghan) (tazkira) Position: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref): AFG0094 (UN Ref): TAi.121 (Further Identifying Information): Belongs to Hotak tribe. Review pursuant to Security Council resolution 1822 (2008) was concluded on 29 Jul. 2010. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/ Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here. Listed On: 23/02/2001 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 01/02/2021 Group ID: 7055. 3. ABDUL AHMAD TURK, Abdul Ghani Baradar Title: Mullah DOB: --/--/1968. -

Afghanistan Mid-Year Report 2015: Protection of Civilians In

AFGHANISTAN MIDYEAR REPORT 2015 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT © 2015/Reuters United Nations Assistance Mission United Nations Office of the High in Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan August 2015 Source: UNAMA GIS January 2012 AFGHANISTAN MIDYEAR REPORT 2015 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT United Nations Assistance Mission in United Nations Office of the High Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan August 2015 Photo on Front Cover © 2015/Reuters. A man assists an injured child following a suicide attack launched by Anti-Government Elements on 18 April 2015, in Jalalabad city, Nangarhar province, which caused 158 civilian casualties (32 deaths and 126 injured, including five children). Photo taken on 18 April 2015. UNAMA documented a 78 per cent increase in civilian casualties attributed to Anti-Government Elements from complex and suicide attacks in the first half of 2015. "The cold statistics of civilian casualties do not adequately capture the horror of violence in Afghanistan, the torn bodies of children, mothers and daughters, sons and fathers. The statistics in this report do not reveal the grieving families and the loss of shocked communities of ordinary Afghans. These are the real consequences of the conflict in Afghanistan.” Nicholas Haysom, United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary- General in Afghanistan, Kabul, August 2015. “This is a devastating report, which lays bare the heart-rending, prolonged suffering of civilians in Afghanistan, who continue to bear the brunt of the armed conflict and live in insecurity and uncertainty over whether a trip to a bank, a tailoring class, to a court room or a wedding party, may be their last.