Country of Origin Report Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress in Afghanistan Bucharest Summit2-4 April 2008 Progress in Afghanistan

© MOD NL © MOD Canada © MOD Canada Progress in Afghanistan Progress in Bucharest Summit 2-4 April 2008 Bucharest Summit2-4 Progress in Afghanistan Contents page 1. Foreword by Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy, ..........................1 Jean-François Bureau, and NATO Spokesman, James Appathurai 2. Executive summary .........................................................................................................................................2 3. Security ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 • IED attacks and Counter-IED efforts 4 • Musa Qala 5 • Operations Medusa successes - Highlights Panjwayi and Zhari 6 • Afghan National Army 8 • Afghan National Police 10 • ISAF growth 10 4. Reconstruction and Development ............................................................................................... 12 • Snapshots of PRT activities 14 • Afghanistan’s aviation sector: taking off 16 • NATO-Japan Grant Assistance for Grassroots Projects 17 • ISAF Post-Operations Humanitarian Relief Fund 18 • Humanitarian Assistance - Winterisation 18 5. Governance ....................................................................................................................................................... 19 • Counter-Narcotics 20 © MOD Canada Foreword The NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission is approaching five years of operations in Afghanistan. This report is a -

CB Meeting PAK/AFG

Polio Eradication Initiative Afghanistan Current Situation of Polio Eradication in Afghanistan Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 29-30 April 2015,Abu Dhabi AFP cases Classification, Afghanistan Year 2013 2014 2015 Reported AFP 1897 2,421 867 cases Confirmed 14 28 1 Compatible 4 6 0 VDPV2 3 0 0 Discarded 1876 2,387 717 Pending 0 0 *149 Total of 2,421 AFP cases reported in 2014 and 28 among them were confirmed Polio while 6 labelled* 123as Adequatecompatible AFP cases Poliopending lab results 26 Inadequate AFP cases pending ERC 21There Apr 2015 is one Polio case reported in 2015 as of 21 April 2015. Region wise Wild Poliovirus Cases 2013-2014-2015, Afghanistan Confirmed cases Region 2013 2014 2015 Central 1 0 0 East 12 6 0 2013 South east 0 4 0 Districts= 10 WPV=14 South 1 17 1 North 0 0 0 Northeast 0 0 0 West 0 1 0 Polio cases increased by 100% in 2014 Country 14 28 1 compared to 2013. Infected districts increased 2014 District= 19 from 10 to 19 in 2014. WPV=28 28 There30 is a case surge in Southern Region while the 25Eastern Region halved the number of cases20 in comparison14 to 2013 Most15 of the infected districts were in South, East10 and South East region in 2014. No of AFP cases AFP of No 1 2015 5 Helmand province reported a case in 2015 District= 01 WPV=01 after0 a period of almost two months indicates 13 14 15 Year 21continuation Apr 2015 of low level circulation. Non Infected Districts Infected Districts Characteristics of polio cases 2014, Afghanistan • All the cases are of WPV1 type, 17/28 (60%) cases are reported from Southern region( Kandahar-13, Helmand-02, and 1 each from Uruzgan and Zabul Province). -

Freedom Or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 Spring 2005 Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Hannibal Travis, Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq, 3 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 1 (2005). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2005 Northwestern University School of Law Volume 3 (Spring 2005) Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights FREEDOM OR THEOCRACY?: CONSTITUTIONALISM IN AFGHANISTAN AND IRAQ By Hannibal Travis* “Afghans are victims of the games superpowers once played: their war was once our war, and collectively we bear responsibility.”1 “In the approved version of the [Afghan] constitution, Article 3 was amended to read, ‘In Afghanistan, no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.’ … This very significant clause basically gives the official and nonofficial religious leaders in Afghanistan sway over every action that they might deem contrary to their beliefs, which by extension and within the Afghan cultural context, could be regarded as -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

Afghanistan-Pakistan Media Affairs Challenges and Opportunities

Afghanistan-Pakistan Media Affairs Challenges and Opportunities Rahimullah Yusufzai December 2018 The media in Afghanistan and Pakistan has never been so large, vibrant and independent. It has attained unimaginable power and become a key player in politics and other walks of life. Media is the fourth pillar of the state and democracy in both Afghanistan and Pakistan in the true sense of the word. Earlier, it was the mainstream print and electronic media that was dominant and had assumed unprecedented importance. Now the social media is making an impact in these two neighbouring countries and often taking the lead in breaking news even if it has lesser credi- bility than the mainstream media. The media has tended to be overly patriotic and at times even aggres- sive in context of the perceived national interests of Afghanistan and Pakistan. The poor relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan affect the work of journalists. There is generally lack of awareness about each other due to the virtual absence of Afghan media in Pakistan and Pakistani media in Afghanistan. Table of Contents List of Acronyms i Foreword iii Rise in Media Power 1 Fallout on Media of Poor Afghanistan-Pakistan Relations 3 Status of Afghan Media in Pakistan 4 Status of Pakistani Media in Afghanistan 7 Reasons of Information Vacuum Between Neighbours 8 Creating Culture of Engagement – Establishing Institutional Relations 9 Between Media Stakeholders Impact of Regional Dynamics on Afghanistan-Pakistan Media 11 Relations – What Went Wrong Recommendations for States, Media -

RELEASE in PART B5,B6 From: Sent: To: Subject: Mchale, Judith a <[email protected]> Thursday, December 9, 2010 8:11 PM RE

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05777946 Date: 08/31/2015 RELEASE IN PART B5,B6 From: McHale, Judith A <[email protected]> Sent: Thursday, December 9, 2010 8:11 PM To: Subject: RE: LA Times/Laura King - Afghan TV police drama delivers message with zest In Singapore now heading back this afternoon. Bali Forum interesting although some of the speeches (Iran) were predictably tedious. No wiki mentions anywhere. Remind me to tell you about the Timor slamming of MCC. The joys of foreign travel. See you Monday. jm Original Message From: H [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, December 09, 2010 5:41 AM To: McHale, Judith A Subject: Re: LA Times/Laura King - Afghan TV police drama delivers message with zest Can't wait to see you and catch upand hear about Bali! Thx for all you're doing and everywhere you're carrying the message. Original Message From: McHale, Judith A <[email protected]> To: H Sent: Wed Dec 08 14:00:19 2010 Subject: Fw: LA Times/Laura King - Afghan TV police drama delivers message with zest Interesting approach towards influencing nonular attiturips I'm speaking at the Democracy conference in Bali today and then heading home tomorrow. Had a great trip to Indonesia. Was also in Malaysia and met with Paul Jones on the educational initiative. See you next week. Jm From: Sreebny, Daniel To: McHale, Judith A; DiMartino, Kitty; Cormack, Maureen E; Schwartz, Larry R/PPR; Whitaker, Elizabeth A; Cedar, Andrew N Cc: Sreebny, Daniel; Hensman, Chris D; Namba, Nicholas; Kenna, Corley; Guimond, Gabrielle; Moore, James R Sent: Wed Dec 08 09:30:55 2010 Subject: LA Times/Laura King - Afghan TV police drama delivers message with zest latimes.com/news/nationworld/world/la-fg-afghan-cop-show-20101208,0,6019051.story UNCLASSIFIED U.S. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’S Posture Toward Afghanistan Since 2001

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’s Posture toward Afghanistan since 2001 Since the terrorist at- tacks of September 11, 2001, Pakistan has pursued a seemingly incongruous course of action in Afghanistan. It has participated in the U.S. and interna- tional intervention in Afghanistan both by allying itself with the military cam- paign against the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida and by serving as the primary transit route for international military forces and matériel into Afghanistan.1 At the same time, the Pakistani security establishment has permitted much of the Afghan Taliban’s political leadership and many of its military command- ers to visit or reside in Pakistani urban centers. Why has Pakistan adopted this posture of Afghan Taliban accommodation despite its nominal participa- tion in the Afghanistan intervention and its public commitment to peace and stability in Afghanistan?2 This incongruence is all the more puzzling in light of the expansion of insurgent violence directed against Islamabad by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a coalition of militant organizations that are independent of the Afghan Taliban but that nonetheless possess social and po- litical links with Afghan cadres of the Taliban movement. With violence against Pakistan growing increasingly indiscriminate and costly, it remains un- clear why Islamabad has opted to accommodate the Afghan Taliban through- out the post-2001 period. Despite a considerable body of academic and journalistic literature on Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan since 2001, the subject of Pakistani accommodation of the Afghan Taliban remains largely unaddressed. Much of the existing literature identiªes Pakistan’s security competition with India as the exclusive or predominant driver of Pakistani policy vis-à-vis the Afghan Khalid Homayun Nadiri is a Ph.D. -

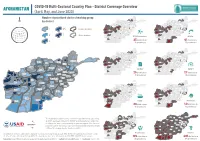

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Humanitarian Overview - Farah Province OCHA Contact: Shahrokh Pazhman

Humanitarian Overview - Farah Province OCHA Contact: Shahrokh Pazhman February 2014 http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info/ Context: Farah province is the most contested in the Western Region with civilians in the northern, central and eastern districts significantly exposed to conflict between ANSF and AGEs. Basic services provision outside of the provincial capital is minimal. The province has few resources, while insecurity has affected the presence and activity of NGOs and the funding of Donors. Key Messages 1. The province has the highest risk profile in the Western Region and one of the highest for Afghanistan as a result of poor access to basic health services, restricted humanitarian access and exposure to drought. Insecurity severely hampers the delivery of basic services and humanitarian assistance to Bala Buluk, Bakwa, Gulistan, and Purchaman. More than a third of the population in the province suffers from poor access to health care centres and very low vaccination coverage. Access strategies as well institutional commitment by relevant departments are urgently required to improve this negative indicator. The limited presence of humanitarian organization must be offset by additional monitoring from Hirat-based regional clusters and regular engagement with provincial authorities. People in Need Population (CSO 2012) Humanitarian Organizations Transition Status Present with Current Operations 6,302 conflict IDPs from Total: 482,400 UNICEF, UNHCR, WHO, IOM, CHA, Fully transferred to the 2011 to 2013 (UNHCR) Male: 51.3% - Female: 48.7% VWO, ARCS, ICRC, and VARA Afghan National Army, 40,033 natural disaster Urban:7.3% - Rural: 92.7% 31 December 2012 affected from 2012 to 2013 (NATO). (IOM) 1,400 evicted from informal settlement (DoRR) plus 1,500 protracted IDPs living under tents since 1990s. -

1 USIP –ADST Afghan Experience Project Interviwe #1 Executive

USIP –ADST Afghan Experience Project Interviwe #1 Executive Summary The interviewee is a Farsi speaker and retired FSO who has had prior Afghan experience, including working with refugees during the period the Taliban was fighting to take over the country in 1995. He returned to Kabul in 2002 as chief of the political section, although retired, for seven months. He returned in 2003 and worked at the U.S. civil affairs mission in Herat for 6 months. He came back later in 2003 to Afghanistan working for the Asia Foundation. He worked on a PRT for approximately three months in late 2004 in Herat. The American presence was minimal when he got there. Security was excellent and the local warlord, Ismael Khan, was using revenues he siphoned from customs houses into development projects. Shortly after subject arrived in Herat, Khan was ousted in a brief battle by forces loyal to Kabul and with the threat of unrest U.S. forces were increased in the area. Our subject suggested to Khan that he make peace with the Kabul government, and he did, perhaps in part on the advice of subject. The Herat PRT had about one hundred American uniformed troops with three civilians, State, AID, Agriculture. Subject was the political advisor to the civil affairs staff, a reserve unit from Minnesota. But much of their work was soon taken over or undercut by the U.S. military task force commander brought in in response to the ouster of Khan. According to subject, the task force commander in the region saw himself as the political expert. -

Re Building the Afghan Army

5HEXLOGLQJWKH$IJKDQDUP\ 'U$QWRQLR*LXVWR]]L&ULVLV6WDWHV3URJUDPPH'HYHORSPHQW5HVHDUFK&HQWUH /6( 7KHDUP\XQGHUWKHPRQDUFK\DQGWKHILUVWUHSXEOLF Some sort of regular army was first established in Afghanistan during the 1860s and 1870s and fought in the Second Anglo-Afghan war. Attempts were made to train this force to European standards, using translated manuals, but the new organisation was never really implemented and the army collapsed early in the war against the British. Another attempt to create a regular army awas made in the 1880s and 1890s by Abdur Rahman Khan, with greater but still limited success, despite British subsidies. After the Third Anglo-Afghan war (1919) the army experienced a rapid decline, both because of huge budget cuts and of the internal conflict that climaxed in the 1928-29 civil war. The origins of the modern Afghan regular armed forces date back to the 1920s and 1930s, when the first serious (still not very successful) attempts to establish a disciplined military force were carried out. After virtually disintegrating during 1928- 1929, the army was re-built during the 1930s, under the leadership of king Nadir Shah. The military academy, in charge of educating the lower ranks of the officer corps, was established in 1932, while the top brass were trained in Turkey. By 1938 the Afghan army numbered 90,000 men, a size that would be maintained until the late 1970s. The police was instead a much smaller force of 9,600 men, based in the cities and towns. The Afghan Royal Air Force was created in 1924 and soon acquired its first bombers, whose potential in dealing with tribal revolts had become clear during the Third Anglo-Afghan war (1919), in which the intervention of the British RAF had proved decisive.