The First Anglo-Afghan War, 1839-42 44

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Captain, the Reverend James Leitch Cappell

Captain, the Reverend James Leitch Cappell James’s father was Thomas Cappell. He was born in 1827 in Clonnand, County Meath, Ireland. At the age of eighteen, he enlisted in the 78th (Highlanders) Regiment of Foot, on 17th April 1845, in Dublin. His attestation describes Private T Cappell, No 2428 as 5’ 7’’ tall, with a fresh complexion, green eyes, brown hair and by trade a ’labourer’. During his fourteen years in what was then known as the East Indies, Thomas was promoted to Corporal (17th April 1850) and four years later, to Sergeant (17th January 1854). The 78th (Highlanders) Regiment was in India from 1842, which is where Thomas joined them soon after his initial training was completed. His first taste of action was in Persia where the Anglo- Persian war broke out on 1st November 1856.i In February the following year, the regiment took part in the Battle of Khushab inflicting heavy casualties on the Persian army. After much diplomacy, the war came to an end and the Persians withdrew their forces from the disputed city of Herat, permitting the British to return their troops to India, where they were soon needed for combat as Indian troops (sepoys) in the service of the British East India Company rebelled in Meerut on 10th May 1857 in an uprising that is now known as the Indian Mutiny. Under the leadership of Sir Henry Havelock the 78th Highlanders helped suppress this Indian Rebellion. Its first action was the recapture of Cawnpore in July 1857 and then the relief of Lucknow. -

Arta 2005.001

ARTA 2005.001 St John Simpson - The British Museum Making their mark: Foreign travellers at Persepolis The ruins at Persepolis continue to fascinate scholars not least through the perspective of the early European travellers’ accounts. Despite being the subject of considerable study, much still remains to be discovered about this early phase of the history of archaeology in Iran. The early published literature has not yet been exhausted; manuscripts, letters, drawings and sculptures continue to emerge from European collections, and a steady trickle of further discoveries can be predicted. One particularly rich avenue lies in further research into the personal histories of individuals who are known to have been resident in or travelling through Iran, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries. These sources have value not only in what may pertain to the sites or antiquities, but they also add useful insights into the political and socio-economic situation within Iran during this period (Wright 1998; 1999; Simpson in press; forthcoming). The following paper offers some research possibilities by focusing on the evidence of the Achemenet janvier 2005 1 ARTA 2005.001 Fig. 1: Gate of All Nations graffiti left by some of these travellers to the site. Some bio- graphical details have been added where considered appro- priate but many of these individuals deserve a level of detailed research lying beyond the scope of this preliminary survey. Achemenet janvier 2005 2 ARTA 2005.001 The graffiti have attracted the attention of many visitors to the site, partly because of their visibility on the first major building to greet visitors to the site (Fig. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

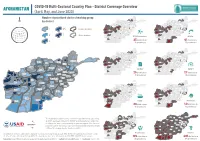

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology. -

Transregional Intoxications Wine in Buddhist Gandhara and Kafiristan

Borders Itineraries on the Edges of Iran edited by Stefano Pellò Transregional Intoxications Wine in Buddhist Gandhara and Kafiristan Max Klimburg (Universität Wien, Österreich) Abstract The essay deals with the wine culture of the Hindu Kush area, which is believed to be among the oldest vinicultural regions of the world. Important traces and testimonies can be found in the Gandharan Buddhist stone reliefs of the Swat valley as well as in the wine culture of former Kafiristan, present-day Nuristan, in Afghanistan, which is still in many ways preserved among the Kalash Kafirs of Pakistan’s Chitral District. Kalash represent a very interesting case of ‘pagan’ cultural survival within the Islamic world. Keywords Kafiristan. Wine. Gandhara. Kalash. Dionysus, the ancient wine deity of the Greeks, was believed to have origi- nated in Nysa, a place which was imagined to be located somewhere in Asia, thus possibly also in the southern outskirts of the Hindu Kush, where Alexander and his Army marched through in the year 327 BCE. That wood- ed mountainous region is credited by some scholars with the fame of one of the most important original sources of the viticulture, based on locally wild growing vines (see Neubauer 1974). Thus, conceivably, it was also the regional viniculture and not only the (reported) finding of much of ivy and laurel which had raised the Greeks’ hope to find the deity’s mythical birth place. When they came across a village with a name similar to Nysa, the question appeared to be solved, and the king declared Dionysus his and the army’s main protective deity instead of Heracles, thereby upgrading himself from a semi-divine to a fully divine personality. -

Voyages & Travel 1515

Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. CONTENTS Africa . 1 Egypt, The Near East & Middle East . 22 Europe, Russia, Turkey . 39 India, Central Asia & The Far East . 64 Australia & The Pacific . 91 Cover illustration; item 48, Walters . Central & South America . 115 MAGGS BROS. LTD. North America . 134 48 BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON WC1B 3DR Telephone: ++ 44 (0)20 7493 7160 Alaska & The Poles . 153 Email: [email protected] Bank Account: Allied Irish (GB), 10 Berkeley Square London W1J 6AA Sort code: 23-83-97 Account Number: 47777070 IBAN: GB94 AIBK23839747777070 BIC: AIBKGB2L VAT number: GB239381347 Prices marked with an *asterisk are liable for VAT for customers in the UK. Access/Mastercard and Visa: Please quote card number, expiry date, name and invoice number by mail, fax or telephone. EU members: please quote your VAT/TVA number when ordering. The goods shall legally remain the property of the seller until the price has been discharged in full. © Maggs Bros. Ltd. 2021 Design by Radius Graphics Printed by Page Bros., Norfolk AFRICA Remarkable Original Artworks 1 BATEMAN (Charles S.L.) Original drawings and watercolours for the author’s The First Ascent of the Kasai: being some Records of service Under the Lone Star. A bound volume containing 46 watercolours (17 not in vol.), 17 pen and ink drawings (1 not in vol.), 12 pencil sketches (3 not in vol.), 3 etchings, 3 ms. charts and additional material incl. newspaper cuttings, a photographic nega- tive of the author and manuscript fragments (such as those relating to the examination and prosecution of Jao Domingos, who committed fraud when in the service of the Luebo District). -

Télécharger Article

ﻣﺠﻠﺔ دراﺳﺎت دﻳﺴﻤﺒﺮ 2015 British Intervention in Afghanistan and its Aftermath (1838-1842) Mehdani Miloud * and Ghomri Tedj * Tahri Mohamed University ( Bechar ) Abstract The balance of power that prompted the European powers to the political domination and economic exploitation of the Third World countries in the nineteenth century was primarily due to the industrialization requirements. In fact, these powers embarked on global expansion to the detriment of fragile states in Africa, South America and Asia, to secure markets to keep their machinery turning. In Central Asia, the competition for supremacy and influence involved Britain and Russia, then two hegemonic powers in the region. Russia’s steady expansion southwards was to cause British mounting concern, for such a systematic enlargement would, in the long term, jeopardize British efforts to protect India, ‘the Crown Jewel.’ In their attempt to cope with such contingent circumstances, the British colonial administration believed that making of Afghanistan a buffer state between India and Russia, would halt Russian expansion. Because this latter policy did not deter the Russians’ southwards extension, Britain sought to forge friendly relations with the Afghan Amir, Dost Mohammad. However, the Russians were to alter these amicable relations, through the frequent visits of their political agents to Kabul. This Russian attitude was to increase British anxiety to such a degree that it developed to some sort of paranoia, which ultimately led to British repeated armed interventions in Afghanistan. Key Words: British, intervention, Afghanistan, Great Game Introduction The British loss of the thirteen colonies and the American independence in 1883 moved Britain to concentrate her efforts on India in which the East India Company had established its foothold from the beginning of the seventeenth century up to the Indian Mutiny (1857). -

IRANIAN INFLUENCE on the CULTURE of the HINDUKUSH Karl Jettmar German Ethnologists Called the Kafirs a Megalithic People 1 2 (&Q

Originalveröffentlichung in: Karl Jettmar (Hrsg.) Cultures of the Hindukush. Selected papers from the Hindu-Kush Cultural Conference held at Moesgard 1970, Wiesbaden 1974, S. 39-43 IRANIAN INFLUENCE ON THE CULTURE OF THE HINDUKUSH Karl Jettmar German ethnologists called the Kafirs a megalithic people 1 2 ("Megalithvolk") or Kafiristan a "megalithic centre" , that is to say, the culture of the Kafirs was considered as a phenomenon strictly separated from the great civilizations of Western Asia. It seemed to be part of a cultural stratum which is otherwise accessible to us only by archaeology of far back periods (.3rd - 2nd millennia B.C.) or ethnography in distant regions (e.g. South east Asia and Indonesia). This tendency can be observed even in recent studies made by Snoy and myself. On the other hand, indologists tried to trace survivals of the religion of the Aryan immigrants to India in the folklore of the 3 mountains. I think such efforts are legitimate. But I would propose to start from a more cautious hypothesis. I think that every explanat ion of the religion of the Kafirs and the Dardic peoples has to take into regard that the singularity of Kafiristan and other mount ain areas indeed is preconditioned by geography but became really effective when the surrounding lowlands were conquered by the expand 4 ing force of Islam. A bar was laid which was not opened before the conversion of the mountain valleys themselves. For Kafiristan proper this means an isolate development between the 11th and the 19th centuries A.D. Before the 2nd millennium A.D. -

Lord Curzon in India: 1898-1903 (1903) H

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1903 Lord Curzon in India: 1898-1903 (1903) H. Caldwell Lipsett Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lipsett, H. Caldwell, "Lord Curzon in India: 1898-1903 (1903)" (1903). Books in English. Paper 2. http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno/2 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LSY 'I.CALDWELL LIPSETT MESSRS EVERETT & CO.'S NEW PUBLIGATIONS A SPORTSWOMAN'SLOVE LETTERS. Fourth Edition. By Fox Russrrr.~,Author of "Colonel Botcherby," " Otltridden," etc. 3s. 6d. THE VIKINGSTRAIN. A Realistic Novel. By A. G. HALES,War Correspondent, Author of " Cnrnpalgn Pictures,'' etc. Illustrated by STANLEV L. WOOD. 6s. i THOMASASSHETON SMITH ; or the Reminiscences of a Famous Fox Hunter. Dy Sir J. E. EARDLEV.WII.DIOT,Bart. A Nerv Edition with an Introduction I,y Sir HZRBERTMAXIVELI., M.P. Illus- trated with nimlerous Engravings. A FRONTIEROFFICER. By 13. CALDWEI.LLIPSETT. 3s. 6d. t 0 DUCHESSI A Trivial Narrative. By W. R. H. TROWBRIDGE, Author of "Letters of her Mother to Elizabeth," "The Grandmother's Advice 1 ,' to Elizabeth," etc. IS. :I ROUNDTHE WORLDWITH A MILLIONAIRE.BYBASILTOZER. I I '' Epaulettes," " Belindn," etc. CAMP FIRESKETCHES. By A. G. Hales, M7ar Correspondent, Author of" Campaign Pictures," "The Viking Strain," etc. IS. TWO POOLS.