Transregional Intoxications Wine in Buddhist Gandhara and Kafiristan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Ecotourism Potential in Pakistan's Biodiversity Project Area (Chitral and Northern Areas): Consultancy Report for IU

Survey of ecotourism potential in Pakistan’s biodiversity project area (Chitral and northern areas): Consultancy report for IUCN Pakistan John Mock and Kimberley O'Neil 1996 Keywords: conservation, development, biodiversity, ecotourism, trekking, environmental impacts, environmental degradation, deforestation, code of conduct, policies, Chitral, Pakistan. 1.0.0. Introduction In Pakistan, the National Tourism Policy and the National Conservation Strategy emphasize the crucial interdependence between tourism and the environment. Tourism has a significant impact upon the physical and social environment, while, at the same time, tourism's success depends on the continued well-being of the environment. Because the physical and social environment constitutes the resource base for tourism, tourism has a vested interest in conserving and strengthening this resource base. Hence, conserving and strengthening biodiversity can be said to hold the key to tourism's success. The interdependence between tourism and the environment is recognized worldwide. A recent survey by the Industry and Environment Office of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP/IE) shows that the resource most essential for the growth of tourism is the environment (UNEP 1995:7). Tourism is an environmentally-sensitive industry whose growth is dependent upon the quality of the environment. Tourism growth will cease when negative environmental effects diminish the tourism experience. By providing rural communities with the skills to manage the environment, the GEF/UNDP funded project "Maintaining Biodiversity in Pakistan with Rural Community Development" (Biodiversity Project), intends to involve local communities in tourism development. The Biodiversity Project also recognizes the potential need to involve private companies in the implementation of tourism plans (PC II:9). -

Initial Appointment to Civil Posts (Relaxation of Upper Age Limit) Rules, 2008

1 GOVERNMENT OF 1[Khyber Pakhtunkhwa] ESTABLISHMENT & ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT (Establishment Wing) NOTIFICATION ST Dated 1 MARCH, 2008 NO.SOE-III(E&AD)2-1/2007, Dated 01-03--2008.---In pursuance of the powers granted under Section 26 of the 2[Khyber Pakhtunkhwa] Civil Servants Act, 1973 (3[Khyber Pakhtunkhwa] Act XVIII of 1973), the competent authority is pleased to make the following rules, namely: THE 4[Khyber Pakhtunkhwa] INITIAL APPOINTMENT TO CIVIL POSTS (RELAXATION OF UPPER AGE LIMIT RULES, 2008) PART — I GENERAL 1. (1) These rules may be called the Initial Appointment to Civil Posts (Relaxation of Upper Age Limit) Rules, 2008. (2) These shall come into force with immediate effect. 5[2. (1) Nothing in these rules shall apply to the appointment in BS-17 and the posts of Civil Judge-Cum-Judicial Magistrate / Illaqa Qazi, BS-18 to be filled through the competitive examination of the Public Service Commission, in which case two years optimum relaxation shall be allowed to: (a) Government servants with a minimum of 2 years continuous service; (b) Disabled persons; and (c) Candidates from backward areas. (2) For appointment to the post of Civil Judge-cum-Judicial Magistrate/Illaqa Qazi, the period which a Barrister or an Advocate of the High Court and /or the Courts subordinate thereto or a Pleader has practiced in the Bar, shall be excluded for the purpose of upper age limit subject to a maximum period of two years from his/her age.] PART — II GENERAL RELAXATION 1 Subs. by the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Act No. IV of 2011 2 Subs. -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

Toward a Consensus on the Nature of Contemporary Insurgency: an Analysis of Counterinsurgency in the War on Terror 2001-2010

Toward a consensus on the nature of contemporary insurgency: an analysis of counterinsurgency in the War on Terror 2001-2010 Erich Julian Elze A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNSW Australia School of International Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences July 2013 1 “What is more important to the history of the world? The Taliban or the collapse of the Soviet empire? Some stirred-up Moslems [sic] or the liberation of Central Europe and the end of the cold war (Brzezinski 1998)?” Zbigniew Brzezinski served as the National Security Advisor to United States President Jimmy Carter. 2 Abstract “Following the terrorist attacks of September 2001, US President George W. Bush announced a War on Terror to promulgate democracy and ameliorate the conditions that spawn terrorism in the Middle East. COIN thus attained a newfound strategic influence since the initiation of regime changes in Afghanistan in 2001 and in Iraq in 2003. This study establishes a conceptual framework for judging COIN utilising the Hybrid War and Insurgent Archipelago models. The Hybrid War model best encapsulates the multi- modal nature of contemporary insurgency which has co-manifested with criminality, nationalism and politicised Islam. This thesis contends that the lack of understanding of the enemy has been of central importance in preventing victory. A case study methodology is utilised to evaluate and compare COIN conducted during the Iraq troop surge and in Afghanistan’s Kunar province. This thesis determines that the positive narrative concerning those COIN campaigns exceeds the actual correlation between COIN and reductions in violence and insurgency. -

Debris Flow Hazard in Chitral

Landform Control on Debris Flow Hazards Hindukush Himalayas Chitral District, N. Pakistan M. Asif Khan & M. Haneef National Centre of Excellence in Geology University of Peshawar Pakistan Objectives: • Identify Debris Flow Hazards on Alluvial Fan Landforms Approaches: • Satellite Images and Field Observations • Morphometric Analysis of Drainage vs Depositional Basins Outcomes: • Develop Understanding of Debris Flow Processes for General Awareness & Mitigation through Engineering Solutions 2 Chitral District, Hindukush Range • Physiography • Habitats • Natural Hazards Quaternary Landforms Mass Movement Landforms • Types • Controlling Tributary Streams • Morphometery Landform Control on Debris Flow Hazards Kohistan N Tibet Himalayas Chitral R. Pamir Knot Hindu Kush 4 Pamirs CHITRAL 5 Physiography •Eastern Hindukush 5500-7500 m high (Tirich Mir Peak 7706 m) Climate •Hindu Raj 5000-7000 m high •34% are above 4500 m asl, with 10% under permanent snow cover •Minimum altitude 1070 m at Arandu. •Relief ranges from 3200 to 6000 m at the eastern face of the Tirich Mir. Climate •high-altitude continental, classified as arid to semi-arid 6 CHITRAL 7 Hindu Raj Chitral Valley Tirich Mir (5706 m) SE NW 8 Upper Chitral Valley, N. Pakistan N 9 10 11 DEBRIS FLOW HAZARD Venzuella Debris Flow- 1999 Deaths: 50,000 Persons affected: 331,164 Homeless: 250,000 Disappeared persons: 7,200 Housing units affected: 63,935 Housing units destroyed: 23,234 12 13 Debris Flow Hazards Settings in Chitral Habitation restricted to River-Bank Terraces Terraced Landforms Flood Plain Recent Alluvial/Debris Fans Remnants of Glacial Moraines Remnant Inter-glacial and Post- Glacial Alluvial fans Chitral R. Recent Debris Flow BUNI 14 N Bedrock Lithologies: PF Purit Fm (S.St; Congl,Shale) DF Drosh Fm (Green Schist) MZ Mélange Zone (Ultramafic blocks, AF6 volcanic rocks, slate) Alluvial Fan Terraces AFT-1-4 Remnant Fans AFT-5,6 Active Fans LFT Lake sediment Terraces Multi-Stage Landform Terraces, Drosh, Chitral, Pakistan 15 Classification of Landforms, Chitral, N. -

IRANIAN INFLUENCE on the CULTURE of the HINDUKUSH Karl Jettmar German Ethnologists Called the Kafirs a Megalithic People 1 2 (&Q

Originalveröffentlichung in: Karl Jettmar (Hrsg.) Cultures of the Hindukush. Selected papers from the Hindu-Kush Cultural Conference held at Moesgard 1970, Wiesbaden 1974, S. 39-43 IRANIAN INFLUENCE ON THE CULTURE OF THE HINDUKUSH Karl Jettmar German ethnologists called the Kafirs a megalithic people 1 2 ("Megalithvolk") or Kafiristan a "megalithic centre" , that is to say, the culture of the Kafirs was considered as a phenomenon strictly separated from the great civilizations of Western Asia. It seemed to be part of a cultural stratum which is otherwise accessible to us only by archaeology of far back periods (.3rd - 2nd millennia B.C.) or ethnography in distant regions (e.g. South east Asia and Indonesia). This tendency can be observed even in recent studies made by Snoy and myself. On the other hand, indologists tried to trace survivals of the religion of the Aryan immigrants to India in the folklore of the 3 mountains. I think such efforts are legitimate. But I would propose to start from a more cautious hypothesis. I think that every explanat ion of the religion of the Kafirs and the Dardic peoples has to take into regard that the singularity of Kafiristan and other mount ain areas indeed is preconditioned by geography but became really effective when the surrounding lowlands were conquered by the expand 4 ing force of Islam. A bar was laid which was not opened before the conversion of the mountain valleys themselves. For Kafiristan proper this means an isolate development between the 11th and the 19th centuries A.D. Before the 2nd millennium A.D. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Nuristan (Kafiristan) and the Kalash Kafirs of Chitral Part One

Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser udgivet af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab Bind 41, nr. 3 Hist. Filos. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. 41, no. 3 (1966) AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NURISTAN (KAFIRISTAN) AND THE KALASH KAFIRS OF CHITRAL PART ONE SCHUYLER JONES With a Map by Lennart Edelberg København 1966 Kommissionær: Munksgaard X Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab udgiver følgende publikationsrækker: The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters issues the following series of publications: Bibliographical Abbreviation. Oversigt over Selskabets Virksomhed (8°) Overs. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Annual in Danish) Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser (8°) Hist. Filos. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter (4°) Hist. Filos. Skr. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (History, Philology, Philosophy, Archeology, Art History) Matematisk-fysiske Meddelelser (8°) Mat. Fys. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. Matematisk-fysiske Skrifter (4°) Mat. Fys. Skr. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Astronomy, Geology) Biologiske Meddelelser (8°) Biol. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. Biologiske Skrifter (4°) Biol. Skr. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Botany, Zoology, General Biology) Selskabets sekretariat og postadresse: Dantes Plads 5, København V. The address of the secretariate of the Academy is: Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Dantes Plads 5, Köbenhavn V, Denmark. Selskabets kommissionær: Munksgaard’s Forlag, Prags Boulevard 47, København S. The publications are sold by the agent of the Academy: Munksgaard, Publishers, 47 Prags Boulevard, Köbenhavn S, Denmark. HISTORI SK-FILOSO FISKE MEDDELELSER UDGIVET AF DET KGL. DANSKE VIDENSKABERNES SELSKAB BIND 41 KØBENHAVN KOMMISSIONÆR: MUNKSGAARD 1965—66 INDHOLD Side 1. H jelholt, H olger: British Mediation in the Danish-German Conflict 1848-1850. Part One. From the MarCh Revolution to the November Government. -

Helps Afghan Police Establish Footprint in Pech Valley

‘TF Cacti’ helps Afghan police establish footprint in Pech Valley. Aug 18, 2011 An F-15 Eagle fighter jet screams above the Pech River Valley, in eastern Afghanistan's Kunar province, for a show of force, right after a firefight between insurgents and troops from Co. D, 2nd Bn., 35th Inf. Regt., “TF Cacti,” 3rd BCT, 25th ID, recently. Story and Photos by Sgt. 1st Class Mark Burrell, Combined Joint Task Force 1-Afghanistan KUNAR PROVINCE, Afghanistan — During the dead of night, in the Pech River Valley, here, they moved into position. High up on the rocky ridgelines that loom over “Route Rhode Island,” Taliban fighters silently crept into fighting positions. There, they hid, waiting for the return of International Security Assistance Forces to the valley. On the winding road below, Afghan National Security Forces and their U.S. counterparts took up fortified security positions at various checkpoints throughout the valley. The sun rose, showering the valley with light, as bullets rained down from above. But Soldiers from Company D, 2nd Battalion, 35th Infantry Regiment, “Task Force Cacti,” 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division, and their ANSF counterparts, were ready for a fight. “It shows that the enemy is not in charge here,” said Capt. Brian Kalaher, commander, Co. D. “The enemy thinks they are, and they say it’s the world’s worst valley … but obviously not. I mean, if they controlled the valley, (I) wouldn’t be sitting here, you know. If they controlled the valley, I wouldn’t live here.” 2nd Lt. Trey VanWyhe, infantry platoon leader, Co. -

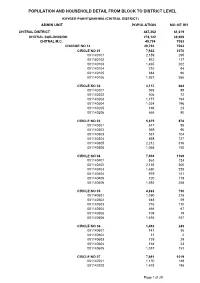

Chitral Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (CHITRAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH CHITRAL DISTRICT 447,362 61,619 CHITRAL SUB-DIVISION 278,122 38,909 CHITRAL M.C. 49,794 7063 CHARGE NO 14 49,794 7063 CIRCLE NO 01 7,933 1070 001140101 2,159 295 001140102 972 117 001140103 1,465 202 001140104 716 94 001140105 684 96 001140106 1,937 266 CIRCLE NO 02 4,157 664 001140201 593 89 001140202 505 72 001140203 1,171 194 001140204 1,024 196 001140205 198 23 001140206 666 90 CIRCLE NO 03 5,875 878 001140301 617 85 001140302 569 96 001140303 551 104 001140304 858 127 001140305 2,212 316 001140306 1,068 150 CIRCLE NO 04 7,939 1169 001140401 863 124 001140402 2,135 300 001140403 1,650 228 001140404 979 141 001140405 720 118 001140406 1,592 258 CIRCLE NO 05 4,883 730 001140501 1,590 218 001140502 448 59 001140503 776 110 001140504 466 67 001140505 109 19 001140506 1,494 257 CIRCLE NO 06 1,492 243 001140601 141 36 001140602 11 2 001140603 139 29 001140604 164 23 001140605 1,037 153 CIRCLE NO 07 7,691 1019 001140701 1,170 149 001140702 1,478 195 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (CHITRAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 001140703 1,144 156 001140704 1,503 200 001140705 1,522 196 001140706 874 123 CIRCLE NO 08 9,824 1290 001140801 2,779 319 001140802 1,605 240 001140803 1,404 200 001140804 1,065 152 001140805 928 124 001140806 974 135 001140807 1,069 120 CHITRAL TEHSIL 228,328 31846 ARANDU UC 23,287 3105 AKROI 1,777 301 001010105 1,777 301 ARANDU -

Religion As a Space for Kalash Identity a Case Study of Village Bumburetin Kalash Valley, District Chitral

World Applied Sciences Journal 29 (3): 426-432, 2014 ISSN 1818-4952 © IDOSI Publications, 2014 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2014.29.03.1589 Religion as a Space for Kalash Identity A Case Study of Village Bumburetin Kalash Valley, District Chitral Irum Sheikh, Hafeez-ur-Rehman Chaudhry and Anwaar Mohyuddin Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract: The study was conducted in Bumburet valley of district Chitral, Pakistan. Qualitative anthropological research technique was adopted for acquiring the ethnographic data for the research in hand. This research paper is an attempt to understand ancestral and cultural traditions, faith, mystic experiences, oral history and mythology of the Kalash people. The natives’ concept of sacred and profane, fundamental principle of purity and impurity and the use of religion as a source of socio political strength have also taken into the account. Religion is a universal phenomenon which has existed even in the Stone Age and preliterate societies and serves as a source of identification for the people. Among the Kalash religion is the main divine force for their cultural identity. Religious identity is constructed both socially and culturally and transmitted to the next generation. The changes brought in the religion are the consequence of asserting power to make it more of cultural and group identity rather than a pure matter of choice based on individual’s inner self or basic fact of birth. The role of Shamans and Qazi is very significant. They teach and preach youth the rituals, offering and sacrifice. The contemporary Kalash believes in one God but the Red Kalash believed in variety of gods and deities, which includes Irma (The Supreme Creator), Dezalik/ disini (goddess of fertility), Sajigor (the warrior god), Bulimain (divider of riches), Maha~deo (god of promise), Ingaw (god of prosperity), Shigan (god of health), Kotsomaiush (goddess of nature and feminism) and Jatch / Zaz (A Super Natural Being). -

Emerging Role of Traditional Birth Attendants in Mountainous Terrain: a Qualitative Exploratory Study from Chitral District, Pakistan

Open Access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006238 on 26 November 2014. Downloaded from Emerging role of traditional birth attendants in mountainous terrain: a qualitative exploratory study from Chitral District, Pakistan Babar Tasneem Shaikh, Sharifullah Khan, Ayesha Maab, Sohail Amjad To cite: Shaikh BT, Khan S, ABSTRACT et al Strengths and limitations of this study Maab A, . Emerging role Objectives: This research endeavours to identify the of traditional birth attendants role of traditional birth attendants (TBAs) in supporting ▪ in mountainous terrain: A study, the first of its kind, which has expounded the maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) care, a qualitative exploratory study on the subject of traditional birth attendants from Chitral District, Pakistan. partnership mechanism with a formal health system (TBAs)’ role and livelihood after the introduction of BMJ Open 2014;4:e006238. and also explored livelihood options for TBAs in the trained maternal, newborn and child health provi- doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014- health system of Pakistan. ders in Pakistan. 006238 Setting: The study was conducted in district Chitral, ▪ The use of qualitative methods provided rich Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, covering the areas insight into women’s interpretations and ▸ Prepublication history for where the Chitral Child Survival programme was decision-making regarding healthcare seeking this paper is available online. implemented. during and after pregnancy in a relatively conser- To view these files please Participants: A qualitative exploratory study was vative setting of Pakistan. The study presents the visit the journal online conducted, comprising seven key informant interviews views of all stakeholders involved in the (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ with health managers, and four focus group discussions intervention. -

Managing War on the Northwest Frontier, 1880-1907

Living with the Problem: Managing War on the Northwest Frontier, 1880-1907 Brian P. Farrell On 22 July 1880 the British government recognized Abdur Rahman Khan as Emir, or ruler, of Afghanistan. This marked the formal end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War. But it made no real impact on a different kind of military conflict, one that overlapped with issues of state between Afghanistan and British India. This was a chronic, low intensity military confrontation in the borderlands that straddled the boundary between the two states. For the British, the problem was that these two conflicts seemed to weave into one. Lepel Griffin, British negotiator in Kabul, presented the Emir with a memorandum that expressed this British point of view, and their principal objective: … since the British Government admits no right of interference by Foreign Powers within Afghanistan, and since both Russia and Persia are pledged to abstain from all interference with the affairs of Afghanistan, it is plain that Your Highness can have no political relations with any foreign Power except with the British Government.1 The poorly defined line of sovereign demarcation between Afghanistan and British India was more than 2000 km long. If the state of Afghanistan remained independent but weak, that could provide physical security against invasion to British India. The British generally agreed this made Afghanistan a strategic buffer zone for their own imperial defence. But there were two fundamental problems. If a weak Afghanistan fell under the control of a strong hostile Power, that Power might use it as a springboard from which to invade India.