Herat: the Key to India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Between God and the Poets

1 Contexts This is a book about four eleventh-century scholars who lived a millennium ago. But it is also a book about ideas that took shape as if the world outside did not exist. The authors involved conceived their accounts of language, divinity, reason, and metaphor as universal accounts of the human condition. They did not see their Muslim, Arabic, Persian, medieval, context as a determining factor in these universal accounts, and neither should we. To claim that eleventh-century Muslim scholars, writing in Arabic, expressed a universal human spirit with just as much purchase on language, mind, and reality as we achieve today is an endorsement of the position in the history of thought made famous by Leo Strauss.1 However, in order to make sense of eleventh-century texts we need to explore the books their authors had read, the debates in which they were taking part, and the a priori commitments they held: this is the methodology for the history of thought advocated by Quentin Skinner.2 THE ELEVENTH CENTURY What can we say about the eleventh century? It was known, in its own calendar, as the fifth century of the Islamic era that started in 622 a.d. with Muḥammad’s emi- gration from Mecca to Medina (al-hiǧrah; hence the name of that calendar: Hiǧrī) and was counted in lunar years thereafter. The different calendars are, of course, a translation problem. The boundaries of the eleventh-century that I am using (1000 1. Strauss (1989). 2. Skinner (2002). 7 8 Contexts and 1100) are not just artificial; they were wholly absent from the imaginations of the scholars who lived between them, for whom those same years were numbered 390 and 493. -

The Causes of the First Anglo-Afghan War

wbhr 1|2012 The Causes of the First Anglo-Afghan War JIŘÍ KÁRNÍK Afghanistan is a beautiful, but savage and hostile country. There are no resources, no huge market for selling goods and the inhabitants are poor. So the obvious question is: Why did this country become a tar- get of aggression of the biggest powers in the world? I would like to an- swer this question at least in the first case, when Great Britain invaded Afghanistan in 1839. This year is important; it started the line of con- flicts, which affected Afghanistan in the 19th and 20th century and as we can see now, American soldiers are still in Afghanistan, the conflicts have not yet ended. The history of Afghanistan as an independent country starts in the middle of the 18th century. The first and for a long time the last man, who united the biggest centres of power in Afghanistan (Kandahar, Herat and Kabul) was the commander of Afghan cavalrymen in the Persian Army, Ahmad Shah Durrani. He took advantage of the struggle of suc- cession after the death of Nāder Shāh Afshār, and until 1750, he ruled over all of Afghanistan.1 His power depended on the money he could give to not so loyal chieftains of many Afghan tribes, which he gained through aggression toward India and Persia. After his death, the power of the house of Durrani started to decrease. His heirs were not able to keep the power without raids into other countries. In addition the ruler usually had wives from all of the important tribes, so after the death of the Shah, there were always bloody fights of succession. -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

2 Trade and the Economy(Second Half Of

ISBN 92-3-103985-7 Introduction 2 TRADE AND THE ECONOMY(SECOND HALF OF NINETEENTH CENTURY TO EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY)* C. Poujol and V. Fourniau Contents Introduction ....................................... 51 The agrarian question .................................. 56 Infrastructure ...................................... 61 Manufacturing and trade ................................ 68 Transforming societies ................................. 73 Conclusion ....................................... 76 Introduction Russian colonization in Central Asia may have been the last phase of an expansion of the Russian state that had begun centuries earlier. However, in terms of area, it represented the largest extent of non-Russian lands to fall under Russian control, and in a rather short period: between 1820 (the year of major political and administrative decisions aimed at the Little and Middle Kazakh Hordes, or Zhuzs) and 1885 (the year of the capture of Merv). The conquest of Central Asia also brought into the Russian empire the largest non-Russian population in an equally short time. The population of Central Asia (Steppe and Turkistan regions, including the territories that were to have protectorate status forced on them) was 9–10 million in the mid-nineteenth century. * See Map 1. 51 ISBN 92-3-103985-7 Introduction Although the motivations of the Russian empire in conquering these vast territories were essentially strategic and political, they quickly assumed a major economic dimension. They combined all the functions attributed by colonial powers -

Kandahar Survey Report

Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report February 1996 AREA Office 17 - E Abdara Road UfTow Peshawar, Pakistan Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report Prepared by Eng. Yama and Eng. S. Lutfullah Sayed ·• _ ....... "' Content - Introduction ................................. 1 General information on Kandahar: - Summery ........................... 2 - History ........................... 3 - Political situation ............... 5 - Economic .......................... 5 - Population ........................ 6 · - Shelter ..................................... 7 -Cost of labor and construction material ..... 13 -Construction of school buildings ............ 14 -Construction of clinic buildings ............ 20 - Miscellaneous: - SWABAC ............................ 2 4 -Cost of food stuff ................. 24 - House rent· ........................ 2 5 - Travel to Kanadahar ............... 25 Technical recommendation .~ ................. ; .. 26 Introduction: Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan/ AREA intends to undertake some rehabilitation activities in the Kandahar province. In order to properly formulate the project proposals which AREA intends to submit to EC for funding consideration, a general survey of the province has been conducted at the end of Feb. 1996. In line with this objective, two senior staff members of AREA traveled to Kandahar and collect the required information on various aspects of the province. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

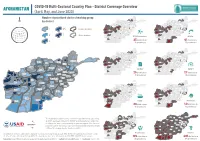

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology. -

Victims of Downing Street: Popular Pressure and the Press in the Stoddart and Conolly Affair, 1838-1845 Sarah E

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2016 Victims of Downing Street: Popular Pressure and the Press in the Stoddart and Conolly Affair, 1838-1845 Sarah E. Kendrick The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Recommended Citation Kendrick, Sarah E., "Victims of Downing Street: Popular Pressure and the Press in the Stoddart and Conolly Affair, 1838-1845" (2016). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 6989. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/6989 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2016 Sarah E. Kendrick The College of Wooster Victims of Downing Street: Popular Pressure and the Press in the Stoddart and Conolly Affair, 1838-1845 by Sarah Emily Kendrick Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of Senior Independent Study Supervised by Professor Johnathan Pettinato Department of History Spring 2016 Abstract During the summer of 1842, Emir Nasrullah of Bukhara, in what is now Uzbekistan, beheaded Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Stoddart and Captain Arthur Conolly, two British officers sent to his kingdom on a diplomatic mission. Reports of the officers’ deaths caused an uproar across Britain, and raised questions about the extent to which Britons abroad were entitled to government protection. Historians have generally examined the officers’ deaths exclusively in the context of the Great Game (the nineteenth century Anglo-Russian rivalry over Central Asia) without addressing the furor the crisis caused in England. -

“Othering” Oneself: European Civilian Casualties and Representations of Gendered, Religious, and Racial Ideology During the Indian Rebellion of 1857

“OTHERING” ONESELF: EUROPEAN CIVILIAN CASUALTIES AND REPRESENTATIONS OF GENDERED, RELIGIOUS, AND RACIAL IDEOLOGY DURING THE INDIAN REBELLION OF 1857 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences Florida Gulf Coast University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree of Masters of Arts in History By Stefanie A. Babb 2014 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in History ________________________________________ Stefanie A. Babb Approved: April 2014 _________________________________________ Eric A. Strahorn, Ph.D. Committee Chair / Advisor __________________________________________ Frances Davey, Ph.D __________________________________________ Habtamu Tegegne, Ph.D. The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Copyright © 2014 by Stefanie Babb All rights reserved One must claim the right and the duty of imagining the future, instead of accepting it. —Eduardo Galeano iv CONTENTS PREFACE v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE HISTORIOGRAPHY 12 CHAPTER TWO LET THE “OTHERING” BEGIN 35 Modes of Isolation 39 Colonial Thought 40 Racialization 45 Social Reforms 51 Political Policies 61 Conclusion 65 CHAPTER THREE LINES DRAWN 70 Outbreak at Meerut and the Siege on Delhi 70 The Cawnpore Massacres 78 Changeable Realities 93 Conclusion 100 CONCLUSION 102 APPENDIX A MAPS 108 APPENDIX B TIMELINE OF INDIAN REBELLION 112 BIBLIOGRAPHY 114 v Preface This thesis began as a seminar paper that was written in conjunction with the International Civilians in Warfare Conference hosted by Florida Gulf Coast University, February, 2012. -

PROCLAMATION 5621—MAR. 20, 1987 101 STAT. 2091 Afghanistan

PROCLAMATION 5621—MAR. 20, 1987 101 STAT. 2091 with protection of national security and rights of privacy. As we celebrate free access to information as part of our heritage, let us honor the memory of President Madison for the wisdom and the devotion to the liberty of the American people that were his credo and his way of life. The Congress, by Public Law 99-539, has designated March 16, 1987, as "Freedom of Information Day" and authorized and requested the President to issue a proclamation in observance of this event. NOW, THEREFORE, I, RONALD REAGAN, President of the United States of America, do hereby proclaim March 16, 1987, as Freedom of Information Day, and I call upon the people of the United States to observe this day with appropriate programs and activities. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this sixteenth day of March, in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and eighty-seven, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and eleventh. RONALD REAGAN Proclamation 5621 of March 20,1987 Afghanistan Day, 1987 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation The people of Afghanistan traditionally celebrate March 21 as the start of their new year. For the friends of the Afghan people, the date has another meaning: it is an occasion to reaffirm publicly our long-standing support of the Afghan struggle for freedom. That struggle seized the attention of the world in December 1979 when a massive Soviet force invaded, murdered one Marxist ruler, installed another, and attempted to crush a widespread resistance movement.