Knowledge on Fire: Attacks on Education in Afghanistan Risks and Measures for Successful Mitigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invest in Afghan Women: a Report on Education in Afghanistan a Checkered History

INVEST IN AFGHAN WOMEN: — A REPORT ON — EDUCATION IN AFGHANISTAN Presented by the George W. Bush Institute’s Women’s Initiative OCTOBER 2O13 “I HOPE AMERICANS WILL JOIN OUR FAMILY IN WORKING TO INVEST IN AFGHAN GIRLS ENSURE THAT DIGNITY AND OPPORTUNITY WILL BE SECURED FOR ALL THE WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF AFGHANISTAN.” In October 2012, a Taliban operative shot 15-year-old Pakistani student Malala Yousafzai in the face and neck while she traveled — MRS. LAURA BUSH home on a school bus. The assassination attempt was punishment for her “crime” of advocating for girls’ education. After surgeons repaired her shattered skull, Malala made a full recovery. And on July 12, 2013, she gave a rousing speech at the United Nations, becoming a global voice for girls’ access to education. Malala’s story is inspiring, but unfortunately the evils she’s combating are all too common in her region of the world. Just next door, in Afghanistan, religious fanaticism and deeply entrenched cultural practices have led to the systematic oppression of women and young girls. The Afghan situation is particularly desperate. While her peers in the United States prepare for their freshman year of high school, a typical 14-year-old Afghan girl has already been forced to leave formal education and is at acute risk of mandated marriage and early motherhood. If she beats the odds and attends school, she has reason to fear an attack on her schoolhouse with grenades or poison. A full 76 percent of her countrywomen have never attended school. And only 12.6 percent can read. -

Download at and Most in Hardcopy for Free from the AREU Office in Kabul

Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Watching Brief Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 The information and views set out in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of AREU and European Union. Editor: Matthew Longmore ISBN: 978-9936-641-34-1 Front cover photo: AREU AREU Publication Code: 1905 E © 2019 This publication may be quoted, cited, or reproduced only for non-commercial purposes and provided that the source is acknowledged. The opinions expessed in this publication are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect that of AREU. Where this publication is reproduced, stored, or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit 2019 Table of Contents About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit .................................................... II Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Past Experiences in Sedentarisation .......................................................................... 2 Sedentarisation Post-2001 ...................................................................................... 3 Drivers of Sedentarisation ......................................................................................... -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

Features of Identity of the Population of Afghanistan

SHS Web of Conferences 50, 01236 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20185001236 CILDIAH-2018 Features of Identity of the Population of Afghanistan Olga Ladygina* Department of History and International Relations, Russian-Tajik Slavonic University, M.Tursunzoda str., 30, Dushanbe, 734025, Tajikistan Abstract. The issues of identity of the population of Afghanistan, which is viewed as a complex self- developing system with the dissipative structure are studied in the article. The factors influencing the development of the structure of the identity of the society of Afghanistan, including natural and geographical environment, social structure of the society, political factors, as well as the features of the historically established economic and cultural types of the population of Afghanistan, i.e. the Pashtuns and Tajiks are described. The author of the article compares the mental characteristics of the bearers of agriculture and the culture of pastoralists and nomads on the basis of description of cultivated values and behavior stereotypes. The study of the factors that influence the formation of the identity of the Afghan society made it possible to justify the argument about the prevalence of local forms of identity within the Afghan society. It is shown that the prevalence of local forms of identity results in the political instability. Besides, it constrains the process of development of national identity and articulation of national idea which may ensure the society consolidation. The relevance of such studies lies in the fact that today one of the threats of Afghanistan is the separatist sentiments coming from the ethnic political elites, which, in turn, negatively affects the entire political situation in the region and can lead to the implementation of centrifugal scenarios in the Central Asian states. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Afghanistan: an Overview

Afghanistan: An Overview by Iraj Bashiri copyright 2002 General information Location and Terrain Afghanistan is a mountainous country centered primarily around the Hindu Kush range of mountains. Nearly three quarters of the country is covered by mountains that range in height anywhere between 3,000 to 4,000 feet. Afghanistan is bound to the north by the three republics of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan; to the east by Tajikistan and China; to the south by Pakistan; and to the west by Iran. The inhabitants of the kingdom live in the river valleys created by the Kabul, Harirud, Andarab, and Hirmand rivers. The economy of Afghanistan is based on wet and dry farming as well as on herding. Afghanistan Overview Topography and Climate The weather in Afghanistan is varied depending on climatic zones. Generally, the winters are cold to mild (32 to 45 F.) and the summers (75 to 90 F.) are hot with no precipitation. No doubt Afghan topography and climate greatly impact transportation and social mobility and hampers the country's progress towards independence and nationhood. Ethnic Mix In 1893, when the Duran line was drawn and modern Afghanistan was created, the region of present-day Islamic Republic of Afghanistan was populated by two main ethnic groups: Indo-European and Turkish. Some pockets of Arab nomads, Hindus, and Jews also lived in the region mostly close to the Panj River valley. The Indo-European population was a continuation of the dominant Indo-Iranian branch in the north and west centered in the cities of Bukhara and Tehran, respectively. The Hindu Kush mountain divided this Indo-Iranian population into four ethnic zones: Pushtuns to the south and southeast; Tajiks to the northeast of the Hindu Kush range; Parsiwans to the west; and Baluch to the southwest The Pushtuns, who later (1950's) made an unsuccessful attempt at creating a Pushtunistan, numbered about 13,000,000. -

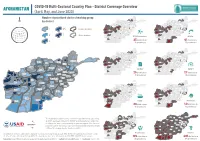

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Afghanistan: Situation Sécuritaire Dans Le District De Nejrab, Province De Kapisa

Afghanistan: situation sécuritaire dans le district de Nejrab, province de Kapisa Recherche rapide de l’analyse-pays Berne, 3 mai 2018 Impressum Editeur Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés OSAR Case postale, 3001 Berne Tél. 031 370 75 75 Fax 031 370 75 00 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.osar.ch CCP dons: 10-10000-5 Version française COPYRIGHT © 2018 Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés OSAR, Berne Copies et impressions autorisées sous réserve de la mention de la source. 1 Introduction Le présent document a été rédigé par l’analyse-pays de l’Organisation suisse d’aide aux ré- fugiés (OSAR) à la suite d’une demande qui lui a été adressée. Il se penche sur les questions suivantes: 1. Quelle est la situation en matière de sécurité dans le district de Nejrab, province de Ka- pisa? 2. Les haut-gradés de l’armée afghane, ainsi que leur famille, font-ils l’objet de menaces de la part des talibans ou d’autres groupes armés d’opposition ? Pour répondre à ces questions, l’analyse-pays de l’OSAR s’est fondée sur des sources ac- cessibles publiquement et disponibles dans les délais impartis (recherche rapide) ainsi que sur des renseignements d’expert-e-s. 2 La situation en matière de sécurité dans le district de Nejrab, province de Kapisa Violence dans la province de Kapisa principalement liée à la lutte d’influence entre le gouvernement et les talibans et à la rivalité entre Jamiat-e Islami et Hezb-e Islami. Selon Fabrizio Foschini, un analyste de l’Aghanistan Analysts Network (AAN), la province de Kapisa serait sociologiquement divisée en deux parties. -

Afghanistan Ghazni Province Land Cover

W # AFGHANISTAN E C Sar-e K har Dew#lak A N # GHAZNI PROVINCE Qarah Qowl( 1) I Qarkh Kamarak # # # # # Regak # # Gowshak # # # Qarah Qowl( 2) R V Qada # # # # # # Bandsang # # Dopushta Panqash # # # # # # # Qashkoh Kholaqol # LAND COVER MAP # Faqir an O # Sang Qowl Rahim Dad # # Diktur (1) # Owr Mordah Dahane Barikak D # Barigah # # # Sare Jiska # Baday # # Kheyr Khaneh # Uchak # R # Jandad # # # # # # # # # # Shakhalkhar Zardargin Bumak # # Takhuni # # # # # # # Karez Nazar # Ambolagh # # # # # # Barikak # # Hesar # # # # # Yarum # # # A P # # # # # # Kataqal'a Kormurda # # # # Qeshlaqha Riga Jusha Tar Bulagh # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # Ahangari # # Kuz Foladay # Minqol # # # Syahreg (2) # # # Maqa # Sanginak # # Baghalak # # # # # # # # # Sangband # Orka B aba # Godowl # Nayak # # # Gadagak # # # # Kota Khwab Altan # # Bahram # # # Katar # # # Barik # Qafak # Qargatak # # # # # # Garmak (3) # # # # # # # # # # Ternawa # # # Kadul # # # # Ghwach # K # # Ata # # # Dandab # # # # # Qole Khugan Sewak (2) Sorkh Dival # # # # # # # # Qabzar (2) # # Bandali # Ajar # Shebar # Hajegak # Sawzsang Podina N ## # # Churka # Nala # # # # # # # Qabzar-1 Turgha # Tughni # Warzang Sultani # # # # # # # # # # # # # Ramzi Qureh Now Juy Negah # # # # # # # # Shew Qowl # Syahsangak A # # # # # # # O # Diktur (2) # Kajak # # Mar Bolagh R V # Ajeda # Gola Karizak # # # Navor Sham # # Dahane Yakhshi Kolukh P # # # # AIMS Y Tanakhak Qal'a-i Dasht I Qole Aymad # Kotal Olsenak Mianah Bed # # # # N Tarbolagh Mar qolak Minqolak Sare Bed Sare Kor ya Ta`ina -

Great Game to 9/11

Air Force Engaging the World Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland COVER Aerial view of a village in Farah Province, Afghanistan. Photo (2009) by MSst. Tracy L. DeMarco, USAF. Department of Defense. Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland Washington, D.C. 2014 ENGAGING THE WORLD The ENGAGING THE WORLD series focuses on U.S. involvement around the globe, primarily in the post-Cold War period. It includes peacekeeping and humanitarian missions as well as Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom—all missions in which the U.S. Air Force has been integrally involved. It will also document developments within the Air Force and the Department of Defense. GREAT GAME TO 9/11 GREAT GAME TO 9/11 was initially begun as an introduction for a larger work on U.S./coalition involvement in Afghanistan. It provides essential information for an understanding of how this isolated country has, over centuries, become a battleground for world powers. Although an overview, this study draws on primary- source material to present a detailed examination of U.S.-Afghan relations prior to Operation Enduring Freedom. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government. Cleared for public release. Contents INTRODUCTION The Razor’s Edge 1 ONE Origins of the Afghan State, the Great Game, and Afghan Nationalism 5 TWO Stasis and Modernization 15 THREE Early Relations with the United States 27 FOUR Afghanistan’s Soviet Shift and the U.S.