The Art and Architecture of Mongolia Christopher P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Currents 31 | 1 Introduction

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title Introduction to "Buddhist Art of Mongolia: Cross-Cultural Connections, Discoveries, and Interpretations" Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5kj9c57m Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(31) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Tsultemin, Uranchimeg Publication Date 2019-06-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction to “Buddhist Art of Mongolia: Cross-Cultural Connections, Discoveries, and Interpretations” Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2019. “Introduction to ‘Buddhist Art of Mongolia: Cross-Cultural Connections, Discoveries, and Interpretations.’” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 1– 6. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/introduction. A comparative and analytical discussion of Mongolian Buddhist art is a long overdue project. In the 1970s and 1980s, Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem’s lavishly illustrated publications broke ground for the study of Mongolian Buddhist art.1 His five-volume work was organized by genre (painting, sculpture, architecture, decorative arts) and included a monograph on a single artist, Zanabazar (Tsultem 1982a, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989). Tsultem’s books introduced readers to the major Buddhist art centers and sites, artists and their works, techniques, media, and styles. He developed and wrote extensively about his concepts of “schools”—including the school of Zanabazar and the school of Ikh Khüree—inspired by Mongolian ger- (yurt-) based education, the artists’ teacher- disciple or preceptor-apprentice relationships, and monastic workshops for rituals and production of art. The very concept of “schools” and its underpinning methodology itself derives from the Medieval European practice of workshops and, for example, the model of scuola (school) evidenced in Italy. -

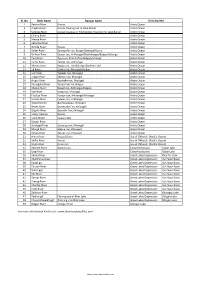

List of Rivers of Mongolia

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora Beyond Tibet

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora beyond Tibet Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2019. “Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Dias- pora beyond Tibet.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 7–32. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/uranchimeg. Abstract This article discusses a Khalkha reincarnate ruler, the First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar, who is commonly believed to be a Géluk protagonist whose alliance with the Dalai and Panchen Lamas was crucial to the dissemination of Buddhism in Khalkha Mongolia. Za- nabazar’s Géluk affiliation, however, is a later Qing-Géluk construct to divert the initial Khalkha vision of him as a reincarnation of the Jonang historian Tāranātha (1575–1634). Whereas several scholars have discussed the political significance of Zanabazar’s rein- carnation based only on textual sources, this article takes an interdisciplinary approach to discuss, in addition to textual sources, visual records that include Zanabazar’s por- traits and current findings from an ongoing excavation of Zanabazar’s Saridag Monas- tery. Clay sculptures and Zanabazar’s own writings, heretofore little studied, suggest that Zanabazar’s open approach to sectarian affiliations and his vision, akin to Tsongkhapa’s, were inclusive of several traditions rather than being limited to a single one. Keywords: Zanabazar, Géluk school, Fifth Dalai Lama, Jebtsundampa, Khalkha, Mongo- lia, Dzungar Galdan Boshogtu, Saridag Monastery, archeology, excavation The First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar (1635–1723) was the most important protagonist in the later dissemination of Buddhism in Mongolia. Unlike the Mongol imperial period, when the sectarian alliance with the Sakya (Tib. -

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

Öndör Gegen Zanabazar and His Role in the Mongolian Culture

Öndör Gegen Zanabazar and his Role in the Mongolian Culture ZSOLT SZILÁGYI In the seventeenth century, Inner Asia witnessed a struggle of armies and ideolo- gies. There was competition between the Manchu Empire and tsarist Russia for greater influence in Inner Asia. It was also a question of whether Tibet and the newly formed Oirat Khaganate would be able to counterbalance them. The terri- torial dividedness of Halha-Mongolia and the ongoing civil war made it unambi- guous that the descendants of the world-conquering Mongols of the thirteenth century could play only a subordinate role in this game. After the collapse of the Great Mongol Empire, the eastern Mongolian territories were divided for three centuries, with only the short intermission of the relatively stable rule of Batu Mongke. The foundation of the Mongolian Buddhist Church in the seventeenth century coincides with this not so prosperous era of Mongolian history. Óndór Gegen, who is known as the founder of the Mongol Buddhist Church, was an active participant in these events. Besides spreading Buddhism, he made indisputable steps to conserve the Mongol traditions and with their help to pro- tect the cultural and social integrity of Mongol society. From the second half of the seventeenth century, the foundation of the Buddhist church gave an opportu- nity for the Mongols to preserve their cultural identity even during the Manchu occupation despite the unifying efforts of the Empire, and later it was an indis- pensable condition of their political independence, too. Let me now show the in- novations which played an important role in the everyday life of the Mongols and which nowadays can be considered as traditional in the resurrection of Mon- golian Buddhism. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

Inner Mongolia

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: CHN30730 Country: China Date: 13 October 2006 Keywords: CHN30730 – Tibetan Buddhism – Government Treatment – Inner Mongolia This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Please provide some background information on this Huang Jiao group. 2. Please provide information on the Chinese government’s treatment of this group, especially in Mongolia. RESPONSE 1. Please provide some background information on this Huang Jiao group. The file indicates that the applicant is from Tongliao, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The applicant claims to practice a religion from Tibet similar to Buddhism. According to the US Department of State, most ethnic Mongolians practice Tibetan Buddhism (US Department of State 2006, International Religious Freedom Report 2006 – China, 15 September, Section 1 – Attachment 1). Huang Jiao means yellow religion in Chinese. One reference to huang jiao was found amongst the sources consulted. The article published in The Drama Review in 1989 reports that huang jiao is the yellow sect of Tibetan Buddhism (Liuyi, Qu et al 1989, ‘The Yi: Human Evolution Theatre’, The Drama Review, Vol 33, No 3, Autumn, p.105 – Attachment 2). The yellow sect of Tibetan Buddhism is more commonly known as Gelug but is also known as Geluk, Gelugpa, Gelukpa, Gelug pa, Geluk pa and the Yellow Hat sect. -

Tuul River Mongolia

HEALTHY RIVERS FOR ALL Tuul River Basin Report Card • 1 TUUL RIVER MONGOLIA BASIN HEALTH 2019 REPORT CARD Tuul River Basin Report Card • 2 TUUL RIVER BASIN: OVERVIEW The Tuul River headwaters begin in the Lower As of 2018, 1.45 million people were living within Khentii mountains of the Khan Khentii mountain the Tuul River basin, representing 46% of Mongolia’s range (48030’58.9” N, 108014’08.3” E). The river population, and more than 60% of the country’s flows southwest through the capital of Mongolia, GDP. Due to high levels of human migration into Ulaanbaatar, after which it eventually joins the the basin, land use change within the floodplains, Orkhon River in Orkhontuul soum where the Tuul lack of wastewater treatment within settled areas, River Basin ends (48056’55.1” N, 104047’53.2” E). The and gold mining in Zaamar soum of Tuv aimag and Orkhon River then joins the Selenge River to feed Burenkhangai soum of Bulgan aimag, the Tuul River Lake Baikal in the Russian Federation. The catchment has emerged as the most polluted river in Mongolia. area is approximately 50,000 km2, and the river itself These stressors, combined with a growing water is about 720 km long. Ulaanbaatar is approximately demand and changes in precipitation due to global 470 km upstream from where the Tuul River meets warming, have led to a scarcity of water and an the Orkhon River. interruption of river flow during the spring. The Tuul River basin includes a variety of landscapes Although much research has been conducted on the including mountain taiga and forest steppe in water quality and quantity of the Tuul River, there is the upper catchment, and predominantly steppe no uniform or consistent assessment on the state downstream of Ulaanbaatar City. -

Zanabazar (1635-1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia

Zanabazar (1635-1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia Uranchimeg Tsultem ___________________________________________________________________________________ This is the author’s manuscript of the article published in the final edited form as: Tsultem, U. (2015). Zanabazar (1635–1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia. In Buddhism in Mongolian History, Culture, and Society (pp. 116–136). Introduction The First Jebtsundamba Khutukhtu (T. rJe btsun dam pa sprul sku) Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar is the most celebrated person in the history of Mongolian Buddhism, whose activities marked the important moments in the Mongolian politics, history, and cultural life, as they heralded the new era for the Mongols. His masterpieces of Buddhist sculptures exhibit a sophisticated accomplishment of the Buddhist iconometrical canon, a craftsmanship of the highest quality, and a refined, yet unfettered virtuosity. Zanabazar is believed to have single-handedly brought the tradition of Vajrayāna Buddhism to the late medieval Mongolia. Buddhist rituals, texts, temple construction, Buddhist art, and even designs for Mongolian monastic robes are all attributed to his genius. He also introduced to Mongolia the artistic forms of Buddhist deities, such as the Five Tath›gatas, Maitreya, Twenty-One T›r›s, Vajradhara, Vajrasattva, and others. They constitute a salient hallmark of his careful selection of the deities, their forms, and their representation. These deities and their forms of representation were unique to Zanabazar. Zanabazar is also accredited with building his main Buddhist settlement Urga (Örgöö), a mobile camp that was to reach out the nomadic communities in various areas of Mongolia and spread Buddhism among them. In the course of time, Urga was strategically developed into the main Khalkha monastery, Ikh Khüree, while maintaining its mobility until 1855. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

ASIAN Philosophy of Protected Areas

ASIAN Philosophy of Protected Areas ! ! ! ! ! Asian Philosophy of Protected Areas Prepared by: Amran Hamzah Dylan Jefri Ong Dario Pampanga Centre for Innovative Planning and Development (CiPD) Faculty of Built Environment Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Skudai, Johor, Malaysia October 2013 ! ! ! ! ! Asian Philosophy of Protected Areas Acknowledgement This report has been prepared for the IUCN Biodiversity Conservation Programme, Asia, with the generous financial support of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The authors would like to thank both the above agencies for their continuous support through the duration of the research, especially to Scott Perkin, the Head of the IUCN Biodiversity Conservation Programme and Tanya Wattanakorn. Many individuals provided assistance in the form of providing information, comments and suggestions and we are indebted to them. We would like to single out the exceptional contributions given by Nigel Crawhall, Les Clark, Lawal Marafa, Robert Blasiak in giving us constructive comments and suggestions to improve the report. Thanks too to the team from the Centre for Innovative Planning and Development (CIPD), Universiti Teknologi Malaysia for carrying out the fieldwork at Kinabalu Park, Sabah and the subsequent analysis. Sabah Parks kindly provided assistance during our fieldwork and we are grateful to its Director, Mr. Paul Basintal and Mr. Maipol Spait for their continuous help. Finally a big thank you to Yong Jia Yaik and Abdullah Lahat for their technical and editorial assistance. Amran Hamzah Dylan -

The Interaction Between Ethnic Relations and State Power: a Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology 5-27-2008 The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911 Wei Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Wei, "The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/33 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTERACTION BETWEEN ETHNIC RELATIONS AND STATE POWER: A STRUCTURAL IMPEDIMENT TO THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CHINA, 1850-1911 by WEI LI Under the Direction of Toshi Kii ABSTRACT The case of late Qing China is of great importance to theories of economic development. This study examines the question of why China’s industrialization was slow between 1865 and 1895 as compared to contemporary Japan’s. Industrialization is measured on four dimensions: sea transport, railway, communications, and the cotton textile industry. I trace the difference between China’s and Japan’s industrialization to government leadership, which includes three aspects: direct governmental investment, government policies at the macro-level, and specific measures and actions to assist selected companies and industries.