Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

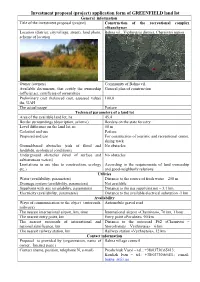

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Moldavia and Maramureş – Micro-Destinations for Relaunching the Romanian Tourism*

Theoretical and Applied Economics Volume XVIII (2011), No. 10(563), pp. 45-56 Moldavia and Maramureş – Micro-destinations * for Relaunching the Romanian Tourism Aurelia-Felicia STĂNCIOIU Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies [email protected] Ion PÂRGARU “Polytechnica” University of Bucharest [email protected] Nicolae TEODORESCU Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies [email protected] Anca-Daniela VLĂDOI Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies [email protected] Monica Paula RAŢIU Romanian American University of Bucharest [email protected] Abstract. Since Romania holds a rich tourism heritage and a great tourism potential, the tourism division into zones was drawn up as “a possibility toward a superior and complex development of the tourism resources, in a unified vision…” (Erdeli, Gheorghilaş, 2006, p. 264), this representing a permanent concern of the specialists from all fields that are related to the tourism management. Although the criteria for selection and ranking of the tourist attractions have been the subject of some controversies, regarding the types of tourism that can be practiced in these areas, there were arrived almost unanimous conclusions. In order to ensure the representativeness and considering that all historical regions of the contemporary Romania are to the same extent micro- destinations with a substantial “tourism heritage”, the regions of Moldavia (including Bukovina) and Maramureş were merged into one for the elaboration of the research that presents, in essence, the main types of tourism and a part of the treasury of Romanian age-old heritage. Keywords: tourism destination; tourism micro-destination; destination image; regional tourism brand; type of tourism; destination marketing. JEL Code: M31. -

CNEWA Canada. Report. Flooding in Ukriane 2020

REPORT: Flooding Relief in Western Ukraine – Summer 2020 Amount received: CA $63,629 Amount used: CA $63,629 Country, Diocese & Location: areas affected by flooding in the Chernivtsi and Ivano-Frankivsk oblasts, Ukraine Timeline, start date/ end date: July 2020 – May 2021 Type of project: emergency Donors: individuals, UCWLC, UGCC eparchies of Saskatoon, Edmonton, archeparchy of Winnipeg Project Summary This report describes the joint effort of Caritas Chernivtsi, Kolomyya and Ivano-Frankivsk to support people who suffered from devastating flooding in the Ukrainian Carpathian Mountains in June 2020. Distribution of Funds (financial details and receipts can be provided upon request) Distribution Expense Amount, CAD Caritas Kolomyya food, furniture, renovation supplies, household appliances, staff salaries, gas $21,527 Caritas Chernivtsi food, bed linen, renovation supplies, household appliances, staff salaries, gas $33,921 Caritas Ivano-Frankivsk drinking water, food, hygiene products, staff salaries, gas $5,000 disbursements, tax receipts, postage, printing, bank fees, reporting, CNEWA admin fee (5%) $3,181 coordination, public relations, etc. TOTAL: $63,629 Overview All Caritas branches reported to CNEWA about successful completion of their projects. Flooding relief was provided in two stages: 1. Early stage – July-September 2020 - emergency right after the flood – delivery of humanitarian aid, including fresh water, food and essentials 2. Later stage – September 2020-May 2021– restoration and getting ready for winter – providing furniture, renovation supplies, household appliances and helping to restore homesteads All Caritas branches managed to address people’s needs in the early stage. Caritas Kolomyya used funds for later stage by the end of 2020. Caritas Chernivtsi provided bed linen in 2020 and resumed their relief efforts in 2021. -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

![Pdf [In Ukrainian] Pratsi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8575/pdf-in-ukrainian-pratsi-1678575.webp)

Pdf [In Ukrainian] Pratsi

МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ДРОГОБИЦЬКИЙ ДЕРЖАВНИЙ ПЕДАГОГІЧНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ ІМЕНІ ІВАНА ФРАНКА MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE DROHOBYCH IVAN FRANKO STATE PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY ISSN 2519-058X (Print) ISSN 2664-2735 (Online) СХІДНОЄВРОПЕЙСЬКИЙ ІСТОРИЧНИЙ ВІСНИК EAST EUROPEAN HISTORICAL BULLETIN ВИПУСК 17 ISSUE 17 Дрогобич, 2020 Drohobych, 2020 Рекомендовано до друку Вченою радою Дрогобицького державного педагогічного університету імені Івана Франка (протокол від 30 листопада 2020 року № 17) Наказом Міністерства освіти і науки України збірник включено до КАТЕГОРІЇ «А» Переліку наукових фахових видань України, в яких можуть публікуватися результати дисертаційних робіт на здобуття наукових ступенів доктора і кандидата наук у галузі «ІСТОРИЧНІ НАУКИ» (Наказ МОН України № 358 від 15.03.2019 р., додаток 9). Східноєвропейський історичний вісник / [головний редактор В. Ільницький]. – Дрогобич: Видавничий дім «Гельветика», 2020. – Випуск 17. – 286 с. Збірник розрахований на науковців, викладачів історії, аспірантів, докторантів, студентів й усіх, хто цікавиться історичним минулим. Редакційна колегія не обов’язково поділяє позицію, висловлену авторами у статтях, та не несе відповідальності за достовірність наведених даних і посилань. Головний редактор: Ільницький В. І. – д.іст.н., проф. Відповідальний редактор: Галів М. Д. – д.пед.н., доц. Редакційна колегія: Манвідас Віткунас – д.і.н., доц. (Литва); Вацлав Вєжбєнєц – д.габ. з іс- торії, проф. (Польща); Дочка Владімірова-Аладжова – д.філос. з історії (Болгарія); Дюра Гарді – д.філос. з історії, професор (Сербія); Дарко Даровец – д. філос. з історії, проф. (Італія); Дегтярьов С. І. – д.і.н., проф. (Україна); Пол Джозефсон – д. філос. з історії, проф. (США); Сергій Єкельчик – д. філос. з історії, доц. (Канада); Сергій Жук – д.і.н., проф. (США); Саня Златановіч – д.філос. -

Alcohol Consumption and the Soberness Movement of Ruthenians of Bukovina in Their Polyethnic Environment in the Second Half of the 19Th - Early 20Th Centuries

https://doi.org/10.4316/CC.2021.01.006 ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION AND THE SOBERNESS MOVEMENT OF RUTHENIANS OF BUKOVINA IN THEIR POLYETHNIC ENVIRONMENT IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 19TH - EARLY 20TH CENTURIES Borys SAVCHUK1 , Maria OLIYNYK2 , Ștefan PURICI3 , Halyna BILAVYCH1 1 Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University, Ivano-Frankivsk (Ukraine) 2 Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University (Ukraine) 3 Stefan cel Mare University of Suceava (Romania) E-mails: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: The study considers the implications of alcohol production and use, as well as the evolution of the abstinence movement among the Ukrainian population of Bukovina in the second half of the 19th - early 20th centuries in, a polyethnic context. The authors examined the state and local authorities' policies on alcoholic beverage marketing. The reactions of the Ruthenians in Bukovina to anti-alcohol campaigns that occurred among other ethnic groups in the region are explored. Keywords: Bukovina, alcoholism, soberness movement, anti-alcohol struggle, Ruthenians, ethnic communities. Rezumat: Consumul de alcool și mișcarea de abstinență la rutenii din Bucovina în a doua jumătate a secolului al XIX-lea – începutul secolului XX, în context multietnic. Studiul abordează problema consumului de alcool și afirmarea mișcării de abstinență în rândul populației ucrainene din Bucovina în a doua jumătate a secolului al XIX-lea – începutul secolului XX, în context multietnic. Autorii analizează politica statului și autorităților locale în ceea ce privește comercializarea băuturilor alcoolice. Sunt prezentate reacțiile rutenilor bucovineni în contextul mișcărilor de combatere a alcoolismului ce s-au manifestat la nivelul celorlalte grupuri etnice din Bucovina. -

SGGEE Ukrainian Gazetteer 201908 Other.Xlsx

SGGEE Ukrainian gazetteer other oblasts © 2019 Dr. Frank Stewner Page 1 of 37 27.08.2021 Menno Location according to the SGGEE guideline of October 2013 North East Russian name old Name today Abai-Kutschuk (SE in Slavne), Rozdolne, Crimea, Ukraine 454300 331430 Абаи-Кучук Славне Abakly (lost), Pervomaiske, Crimea, Ukraine 454703 340700 Абаклы - Ablesch/Deutsch Ablesch (Prudy), Sovjetskyi, Crimea, Ukraine 451420 344205 Аблеш Пруди Abuslar (Vodopiyne), Saky, Crimea, Ukraine 451837 334838 Абузлар Водопійне Adamsfeld/Dsheljal (Sjeverne), Rozdolne, Crimea, Ukraine 452742 333421 Джелял Сєверне m Adelsheim (Novopetrivka), Zaporizhzhia, Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine 480506 345814 Вольный Новопетрівка Adshiaska (Rybakivka), Mykolaiv, Mykolaiv, Ukraine 463737 312229 Аджияск Рибаківка Adshiketsch (Kharytonivka), Simferopol, Crimea, Ukraine 451226 340853 Аджикечь Харитонівка m Adshi-Mambet (lost), Krasnohvardiiske, Crimea, Ukraine 452227 341100 Аджи-мамбет - Adyk (lost), Leninske, Crimea, Ukraine 451200 354715 Адык - Afrikanowka/Schweigert (N of Afrykanivka), Lozivskyi, Kharkiv, Ukraine 485410 364729 Африкановка/Швейкерт Африканівка Agaj (Chekhove), Rozdolne, Crimea, Ukraine 453306 332446 Агай Чехове Agjar-Dsheren (Kotelnykove), Krasnohvardiiske, Crimea, Ukraine 452154 340202 Агьяр-Джерень Котелникове Aitugan-Deutsch (Polohy), Krasnohvardiiske, Crimea, Ukraine 451426 342338 Айтуган Немецкий Пологи Ajkaul (lost), Pervomaiske, Crimea, Ukraine 453444 334311 Айкаул - Akkerman (Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi), Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, Odesa, Ukraine 461117 302039 Белгород-Днестровский -

Implementation of Romanian Agrarian Reform Regulations in Bessarabia and Bucovina During Between-War Period

IMPLEMENTATION OF ROMANIAN AGRARIAN REFORM REGULATIONS IN BESSARABIA AND BUCOVINA DURING BETWEEN-WAR PERIOD Oleksandr Rusnak Yuriy Fed’kovych Chernivtsi National University, Ukraine Rezumat: Articolul vorbeşte despre realizarea condiţiilor reformei agrare din anii 1920-1921 în Bucovina şi Basarabia. O bună parte din materialele periodice şi documente de arhivă, care se referă la această problemă încă nu sunt folosite pe deplin în literatura ştiinţifică. Cercetarea întreprinsă de autor permite oglindirea unor realităţi concrete în unele judeţe ale Bucovinei şi Basarabiei. Materialul colecţionat mărturiseşte, că în general în regiunea cercetată condiţiile reformei se îndeplineau. Suprapopularea agrară n-a permis împroprietărirea ţăranilor cu pământ. Rezolvarea acestei probleme în condiţiile de atunci a fost imposibilă, deoarece în ţinut nu erau destule terenuri agricole. Trebuie menţionat şi aspectul pozitiv al reformei agrare: după înfăptuirea ei, corelaţia între moşieri şi micii proprietari de pământ se schimbă – zeci de mii de ţărani au fost împroprietăriţi cu pământ. Abstract: The article talks about achieving conditions of agrarian reform in the years 1920-1921, in Bukovina and Bessarabia. The journals and archival documents, which refer to this problem, are not fully used in the scientific literature. The research proposed by the author allows a reflection of agrarian realities in some counties of Bukovina and Bessarabia. It is an attempt to review the basic stages of this process. The collected material proved that in the region, the conditions for a reform were fulfilled. The agrarian overcrowding did not allow authorities to give land to all peasants. Solving this problem, at that time, was impossible, because of the lack of arable land in a specific region. -

CIUS Newsletter 2010

CIUS Newsletter 2010 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies 4-30 Pembina Hall, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2H8 Italian Scholar’s Lecture Represents a Milestone in the Study of the Holodomor The great Ukrainian-Kuban famine of 1932–33—the Holodomor—was one of the determinative events of the twentieth century. Nevertheless, it was largely ignored by scholars until the last few years of the existence of the Soviet Union. One of the scholars who began studying the famine in the late 1980s was Andrea Graziosi, now an internationally recognized specialist on the Soviet state and its policies toward the peasantry and one of the world’s leading authorities on the Holodomor. From 14 to 21 November 2009 he vis- ited Toronto and Edmonton to lecture on “The Holodomor and the Soviet Famines, 1931–33.” The title of the lecture is indica- Monument to victims of the 1932‒33 Holodomor in Ukraine on a hill of the Kyivan Cave Mon- tive of Dr. Graziosi’s comprehensive astery. Photo: Andy Ignatov approach to the study of the Holodo- identified some of its special features peasants from Ukraine and the Kuban mor in Soviet Ukraine and the Kuban and national characteristics. Particu- to leave for other areas of the USSR in within the context of Soviet state policy larly telling, in his view, were Moscow’s search of food. toward the peasantry from 1917 to exclusive policies taken against the Dr. Graziosi also noted other 1933 and, more particularly, the pan- peasantry in Ukraine and the Kuban measures taken against Ukrainians in Soviet famines of 1931–33, including region in the North Caucasus, which this period or immediately afterward. -

Ancestree Summer

SUMMER 2019 VOLUME 40—2 !!!AncesTree! ! The Nanaimo Family History Society Quarterly Journal ISSN 1185-166X (Print)/ISSN 1921-7889 (Online) ! President’s Message What’s Inside by Dean Ford President’s Message Pages 1-2 Well, it looks like summer is here again. Where has the year gone? It is time to take a break from Genealogy News Briefs Pages 3-5 our monthly meetings and enjoy the summer. Most of us take some time away from researching our Settling in Saskatchewan Pages 6-9 families at this time of year and bundle up our projects, and take them to a family reunion. We Desire of My Heart Pages 10-11 will be taking some time to visit new family in Faces of Our Ancestors Page 12 Portland after receiving a DNA match for Veronica. You never know who you will meet on your travels. A Bonnet Family Reunion Pages 13-14 If you have a summer trip planned, have fun and drive safely. What will Happen to Your Pages 15-16 Heirlooms? The NFHS has now placed some of our library books DNA Corner — Summer Reads Page 17 at the LDS Family History Centre on Glen Eagle Crescent and we encourage our members to stop by Future Guest Speakers Page 18 and use the resources as well as sign out books. More books will be added over the months to come. Web Updates Page 19 As of this issue, the books from Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba are available at the LDS Members’ Miscellany Page 20 for both NFHS and LDS members to sign out.