Alcohol Consumption and the Soberness Movement of Ruthenians of Bukovina in Their Polyethnic Environment in the Second Half of the 19Th - Early 20Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

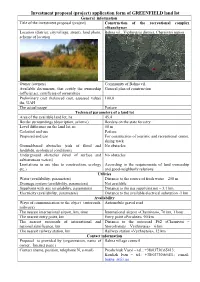

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

Vasyl BOTUSHANSKYY(Chernivtsi) the SOURCES of STATE

Vasyl BOTUSHANSKYY(Chernivtsi) THE SOURCES OF STATE ARCHIVES OF CHERNIVTSI REGION AS COMPONENT OF STUDIING THE EVENTS OF THE WORLD WAR I AT BUKOVYNA This article gives an overview of the sources of the State Archives of Chernivtsi region, including funds of the Austrian and Russian occupation administrations acting in Bukovina in 1914 - 1918, which recorded information about the events of World War I in the region and that can serve as sources for research of the history of these events. Keywords: Bucovina, archive, fund, information, military, troops, war, occupation, empire, requisition, refugees, internment, deportation. 1914 year - the year of the First World War, but not last, and a hundred years it was the most ambitious and bloody war, which is known to humanity, killed 10 million. People., Injuring about 20 million. The war engulfed vast areas of the world, first of all the leading countries of military-political blocs: the Triple (Germany and Austria-Hungary) and the Entente (Russia, Great Britain and France). Have covered the war and area of residence of the Ukrainian people - eastern Ukraine, which was part of the Russian Empire and the West in the empire of Austria-Hungary, including Galicia and Bukovina. Ukrainian tragedy of this war was that mobilized in the opposite army, they were forced to kill each other. Coverage of the history of World War II Ukrainian lands, including and Bukovina, has dedicated many works, and this research continues. Of course, they would have been impossible without the historical sources. For the sake of objectivity it should be recognized that archaeography Bukovina already has on this issue considerable achievements, but many more sources should be identified and investigated. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

APPLICATION of the CHARTER in UKRAINE 2Nd Monitoring Cycle A

Strasbourg, 15 January 2014 ECRML (2014) 3 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES APPLICATION OF THE CHARTER IN UKRAINE 2nd monitoring cycle A. Report of the Committee of Experts on the Charter B. Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the application of the Charter by Ukraine The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages provides for a control mechanism to evaluate how the Charter is applied in a State Party with a view to, where necessary, making recommendations for improving its language legislation, policy and practices. The central element of this procedure is the Committee of Experts, set up under Article 17 of the Charter. Its principal purpose is to report to the Committee of Ministers on its evaluation of compliance by a Party with its undertakings, to examine the real situation of regional or minority languages in the State and, where appropriate, to encourage the Party to gradually reach a higher level of commitment. To facilitate this task, the Committee of Ministers adopted, in accordance with Article 15, paragraph1, an outline for periodical reports that a Party is required to submit to the Secretary General. The report should be made public by the State. This outline requires the State to give an account of the concrete application of the Charter, the general policy for the languages protected under Part II and, in more precise terms, all measures that have been taken in application of the provisions chosen for each language protected under Part III of the Charter. The Committee of Experts’ first task is therefore to examine the information contained in the periodical report for all the relevant regional or minority languages on the territory of the State concerned. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Wildcat (Felis Silvestris Schreber, 1777) in Ukraine: Modern State of the Populations and Eastwards

WILDCAT (FELIS SILVESTRIS SCHREBER, 1777) IN UKRAINE: MODERN STATE OF THE POPULATIONS AND EASTWARDS... 233 UDC 599.742.73(477) WILDCAT (FELIS SILVESTRIS SCHREBER, 1777) IN UKRAINE: MODERN STATE OF THE POPULATIONS AND EASTWARDS EXPANSION OF THE SPECIES I. Zagorodniuk1, M. Gavrilyuk2, M. Drebet3, I. Skilsky4, A. Andrusenko5, A. Pirkhal6 1 National Museum of Natural History, NAS of Ukraine 15, Bohdan Khmelnytskyi St., Kyiv, 01601, Ukraine e-mail: [email protected] 2 Bohdan Khmelnitsky National University of Cherkasy 81, Shevchenko Blvd., Cherkasy 18031, Ukraine 3 National Nature Park “Podilski Tovtry” 6, Polskyi Rynok Sq., Kamianets-Podilskyi 32301, Khmelnytsk Region, Ukraine 4 Chernivtsi Regional Museum, 28, O. Kobylianska St., Chernivtsi 58002, Ukraine 5 National Nature Park “Bugsky Hard” 83, Pervomaiska St., Mygia 55223, Pervomaisky District, Mykolaiv Region, Ukraine 6 Vinnytsia Regional Laboratory Centre, 11, Malynovskyi St., Vinnytsya 21100, Ukraine Modern state of the wildcat populations in Ukraine is analyzed on the basis of de- tailed review and analysis of its records above (annotations) and before (detailed ca- dastre) 2000. Data on 71 modern records in 10 administrative regions of Ukraine are summarized, including: Lviv (8), Volyn (1), Ivano-Frankivsk (2), Chernivtsi (31), Khmelnyts kyi (4), Vinnytsia (14), Odesa (4), Mykolaiv (4), Kirovohrad (2) and Cherkasy (1) regions. Detailed maps of species distribution in some regions, and in Ukraine in gene ral, and the analysis of the rates of expansion as well as direction of change in species limits of the distribution are presented. Morphological characteristics of the samples from the territory of Ukraine are described. Keywords: wildcat, state of populations, geographic range, expansion, Ukraine. -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

![Pdf [In Ukrainian] Pratsi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8575/pdf-in-ukrainian-pratsi-1678575.webp)

Pdf [In Ukrainian] Pratsi

МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ДРОГОБИЦЬКИЙ ДЕРЖАВНИЙ ПЕДАГОГІЧНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ ІМЕНІ ІВАНА ФРАНКА MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE DROHOBYCH IVAN FRANKO STATE PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY ISSN 2519-058X (Print) ISSN 2664-2735 (Online) СХІДНОЄВРОПЕЙСЬКИЙ ІСТОРИЧНИЙ ВІСНИК EAST EUROPEAN HISTORICAL BULLETIN ВИПУСК 17 ISSUE 17 Дрогобич, 2020 Drohobych, 2020 Рекомендовано до друку Вченою радою Дрогобицького державного педагогічного університету імені Івана Франка (протокол від 30 листопада 2020 року № 17) Наказом Міністерства освіти і науки України збірник включено до КАТЕГОРІЇ «А» Переліку наукових фахових видань України, в яких можуть публікуватися результати дисертаційних робіт на здобуття наукових ступенів доктора і кандидата наук у галузі «ІСТОРИЧНІ НАУКИ» (Наказ МОН України № 358 від 15.03.2019 р., додаток 9). Східноєвропейський історичний вісник / [головний редактор В. Ільницький]. – Дрогобич: Видавничий дім «Гельветика», 2020. – Випуск 17. – 286 с. Збірник розрахований на науковців, викладачів історії, аспірантів, докторантів, студентів й усіх, хто цікавиться історичним минулим. Редакційна колегія не обов’язково поділяє позицію, висловлену авторами у статтях, та не несе відповідальності за достовірність наведених даних і посилань. Головний редактор: Ільницький В. І. – д.іст.н., проф. Відповідальний редактор: Галів М. Д. – д.пед.н., доц. Редакційна колегія: Манвідас Віткунас – д.і.н., доц. (Литва); Вацлав Вєжбєнєц – д.габ. з іс- торії, проф. (Польща); Дочка Владімірова-Аладжова – д.філос. з історії (Болгарія); Дюра Гарді – д.філос. з історії, професор (Сербія); Дарко Даровец – д. філос. з історії, проф. (Італія); Дегтярьов С. І. – д.і.н., проф. (Україна); Пол Джозефсон – д. філос. з історії, проф. (США); Сергій Єкельчик – д. філос. з історії, доц. (Канада); Сергій Жук – д.і.н., проф. (США); Саня Златановіч – д.філос. -

CIUS Newsletter 2010

CIUS Newsletter 2010 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies 4-30 Pembina Hall, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2H8 Italian Scholar’s Lecture Represents a Milestone in the Study of the Holodomor The great Ukrainian-Kuban famine of 1932–33—the Holodomor—was one of the determinative events of the twentieth century. Nevertheless, it was largely ignored by scholars until the last few years of the existence of the Soviet Union. One of the scholars who began studying the famine in the late 1980s was Andrea Graziosi, now an internationally recognized specialist on the Soviet state and its policies toward the peasantry and one of the world’s leading authorities on the Holodomor. From 14 to 21 November 2009 he vis- ited Toronto and Edmonton to lecture on “The Holodomor and the Soviet Famines, 1931–33.” The title of the lecture is indica- Monument to victims of the 1932‒33 Holodomor in Ukraine on a hill of the Kyivan Cave Mon- tive of Dr. Graziosi’s comprehensive astery. Photo: Andy Ignatov approach to the study of the Holodo- identified some of its special features peasants from Ukraine and the Kuban mor in Soviet Ukraine and the Kuban and national characteristics. Particu- to leave for other areas of the USSR in within the context of Soviet state policy larly telling, in his view, were Moscow’s search of food. toward the peasantry from 1917 to exclusive policies taken against the Dr. Graziosi also noted other 1933 and, more particularly, the pan- peasantry in Ukraine and the Kuban measures taken against Ukrainians in Soviet famines of 1931–33, including region in the North Caucasus, which this period or immediately afterward. -

Ancestree Summer

SUMMER 2019 VOLUME 40—2 !!!AncesTree! ! The Nanaimo Family History Society Quarterly Journal ISSN 1185-166X (Print)/ISSN 1921-7889 (Online) ! President’s Message What’s Inside by Dean Ford President’s Message Pages 1-2 Well, it looks like summer is here again. Where has the year gone? It is time to take a break from Genealogy News Briefs Pages 3-5 our monthly meetings and enjoy the summer. Most of us take some time away from researching our Settling in Saskatchewan Pages 6-9 families at this time of year and bundle up our projects, and take them to a family reunion. We Desire of My Heart Pages 10-11 will be taking some time to visit new family in Faces of Our Ancestors Page 12 Portland after receiving a DNA match for Veronica. You never know who you will meet on your travels. A Bonnet Family Reunion Pages 13-14 If you have a summer trip planned, have fun and drive safely. What will Happen to Your Pages 15-16 Heirlooms? The NFHS has now placed some of our library books DNA Corner — Summer Reads Page 17 at the LDS Family History Centre on Glen Eagle Crescent and we encourage our members to stop by Future Guest Speakers Page 18 and use the resources as well as sign out books. More books will be added over the months to come. Web Updates Page 19 As of this issue, the books from Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba are available at the LDS Members’ Miscellany Page 20 for both NFHS and LDS members to sign out. -

Agroinvest Quarterly Report

AgroInvest Project QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER 1 – DECEMBER 31, 2014 JANUARY 2015 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International. AGROINVEST QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER 1 – DECEMBER 31, 2014 Contract No. AID-121-C-11-00001 AGROINVEST- QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER- DECEMBER 2014 i CONTENTS Acronyms ………………………………………………………………………………... .v Introduction………………………………………………………………………………. .1 Quarterly Highlights…………………………………………………………………….... 2 Section I: Accomplishments and Progress to Date………………………………………. .4 Technical Implementation… ...............................................................................................4 Component 1 ............................................................................................................4 Component 2……………………………………………………………………..21 Component 3…………………………………………………………………......24 Project Communications…………………………...…………………….………29 Gender Integration………………………………………………………….……32 Section II: Deliverables…………………………………………………………………..33 Section III: Challenges and Plans to Overcome Them…………………………………..34 Section IV: Planned Activities for Next Quarter ...……………………………………...36 Section V: Level of Effort Report ……………………………………………………….40 Annexes: Annex 1 Meetings of the National Agrarian & Land Press Club Annex 2 List of Press Publications Highlighting USAID AgroInvest Annex 3 Environmental Mitigation and Monitoring Report Annex 4 Success Story: Protecting Landowners’ Rights with Pro Bono Legal Assistance Annex 5 Success Story: -

Remembering Volodymyr Ivasiuk (1949 – 1979)

8 24 жовтня 2009 р. КУЛЬТУРА Remembering Volodymyr Ivasiuk (1949 – 1979) song, “Chervona Ruta”, (Red ruth). The first public performance was Who murdered Volodymyr Ivasiuk? on September 13, 1970. This was followed by “Vodohray”, (Fountain). “Chervona Ruta” was performed with Olena Kutnetsova, a young music According to M. Masly, ‘the details of Volodymyr Ivasiuk’s death, teacher, as a duet. Olena Kutnetsova recollects: “We were to sing at an however, do not support the official view that he killed himself. They open-air gig in Teatralna Square in Chernivtsi. It was to be broadcast live waited and searched for Volodya for 24 days. Following the mysterious within the framework of a popular TV programme. A big crowd gathered. disappearance of the composer, the search for him was not disclosed In fact, the square was packed to capacity. We sang. The crowd was to the public, the explanation being given that such an announcement ecstatic, and we woke up the next day to find ourselves famous.” would create a disturbance. However, the mass media are daily used Olesya Sandyha continues with the story, Volodymyr’s ‘fame spread not only to help locate people, but sometimes even their pets. [...] It was fast indeed. In 1971 his “Chervona Ruta” won the Best Song of the Year not until May 18, 1979 that Volodymyr Ivasiuk’s body was accidentally award, and his “Vodohray” was the best song of the next year. Not only discovered in the heavy forest near the village Briukhovych near Lviv. One the best in Ukraine but in the whole of the Soviet Union, of which Ukraine couldn’t bring oneself to believe it.