Pdf [In Ukrainian] Pratsi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Influence of Agglomerations on the Development of Tourism in the Lviv Region

Studia Periegetica nr 3(27)/2019 DOI: 10.26349/st.per.0027.03 HALYNA LABINSKA* Influence of Agglomerations on the Development of Tourism in the Lviv Region Abstract. The author proposes a method of studying the influence of agglomerations on the development of tourism. The influence of agglomerations on the development of tourism is -il lustrated by the case of the Lviv region and the use of correlation analysis. In addition, official statistics about the main indicator of the tourism industry by region and city are subjected to centrographic analysis. The coincidence of weight centers confirms the exceptional influence of the Lviv agglomeration on the development of tourism in the region, which is illustrated with a cartographic visualization. Keywords: agglomeration, tourism, research methodology 1. Introduction Urbanization, as a complex social process, affects all aspects of society. The role of cities, especially large cities, in the life of Ukraine and its regions will only grow. The growing influence of cities on people’s lives and their activities was noted in the early 20th century by the professor V. Kubiyovych [1927]. Mochnachuk and Shypovych identified three stages of urbanization in Ukraine during the second half of the 20th century: 1) urbanization as a process of urban growth; 2) suburbanization – erosion of urban nuclei, formation of ag- glomerations; 3) rurbanization – urbanization of rural settlements within urban- ized areas [Mochnachuk, Shypovych 1972: 41-48]. The stage of rurbanization is ** Ivan Franko National University of Lviv (Ukraine), Department of Geography of Ukraine, e-mail: [email protected], orcid.org/0000-0002-9713-6291. 46 Halyna Labinska consistent with the classic definition of “agglomeration” in the context of Euro- pean urbanism: a system that includes the city and its environs (Pierre Merlen and Francoise Shoe). -

Східноєвропейський Історичний Вісник East European Historical Bulletin

МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ДРОГОБИЦЬКИЙ ДЕРЖАВНИЙ ПЕДАГОГІЧНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ ІМЕНІ ІВАНА ФРАНКА MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE DROHOBYCH IVAN FRANKO STATE PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY ISSN 2519-058X (Print) ISSN 2664-2735 (Online) СХІДНОЄВРОПЕЙСЬКИЙ ІСТОРИЧНИЙ ВІСНИК EAST EUROPEAN HISTORICAL BULLETIN ВИПУСК 12 ISSUE 12 Дрогобич, 2019 Drohobych, 2019 Рекомендовано до друку Вченою радою Дрогобицького державного педагогічного університету імені Івана Франка (протокол від 29 серпня 2019 року № 8) Наказом Міністерства освіти і науки України збірник включено до КАТЕГОРІЇ «А» Переліку наукових фахових видань України, в яких можуть публікуватися результати дисертаційних робіт на здобуття наукових ступенів доктора і кандидата наук у галузі «ІСТОРИЧНІ НАУКИ» (Наказ МОН України № 358 від 15.03.2019 р., додаток 9). Східноєвропейський історичний вісник / [головний редактор В. Ільницький]. – Дрогобич: Видавничий дім «Гельветика», 2019. – Вип. 12. – 232 с. Збірник розрахований на науковців, викладачів історії, аспірантів, докторантів, студентів й усіх, хто цікавиться історичним минулим. Редакційна колегія не обов’язково поділяє позицію, висловлену авторами у статтях, та не несе відповідальності за достовірність наведених даних і посилань. Головний редактор: Ільницький В. І. – д.іст.н., доц. Відповідальний редактор: Галів М. Д. – к.пед.н., доц. Редакційна колегія: Манвідас Віткунас – д.і.н., доц. (Литва); Вацлав Вєжбєнєц – д.габ. з історії, проф. (Польща); Дюра Гарді – д.філос. з історії, професор (Сербія); Дарко Даровец – д. фі- лос. з історії, проф. (Італія); Дегтярьов С. І. – д.і.н., проф. (Україна); Пол Джозефсон – д. філос. з історії, проф. (США); Сергій Єкельчик – д. філос. з історії, доц. (Канада); Сергій Жук – д.і.н., проф. (США); Саня Златановіч – д.філос. з етнології та антропо- логії, ст. наук. спів. -

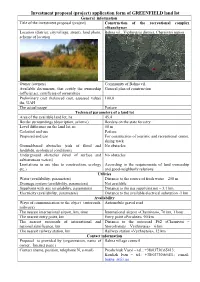

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

BORYS GRINCHENKO KYIV UNIVERSITY "APPROVED" The

BORYS GRINCHENKO KYIV UNIVERSITY "APPROVED" the decision of the Academic Council of Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University 23.03.2017 , Minutes No. 3 Chairman of the Academic Council, Rector ____________ V. Ogneviuk ACADEMIC PROFESSIONAL PROGRAM Educational program: 029.00.02 "Information, Library and Archive Science" the second (master's) level of higher education Branch of knowledge: 02 Art and Culture Specialty: 029 Information, Library and Archive Science Qualification: Master of Information, Library and Archives Launched on 01.09. 2017 (Order from 26.05.2017 p. Number 348) Kyiv - 2017 INTRODUCTION Educational and professional program is developed according to the Law of Ukraine "On Higher Education" with the draft standard 029 specialty Information, Library and Archive Science for the second (master's) level. Developed by a working group consisting of: O. Voskoboynikova-Huzyeva , Doctor in Social Communication, Ph.D., Head of Library and Information Department M. Makarova, Candidate of Sciences in Cultural Studies, Associate Professor of Library and Information Department Z. Sverdlik , Candidate of Historical Sciences., Assistant Professor of Library and Information Department External reviewers: A. Solyanik, Doctor of Pedagogy, Professor, Head of Documentation and Book Science in Kharkiv State Academy of Culture; M. Senchenko , Doctor of Technical Sciences, Professor, Director of the State Scientific Institution " Ivan Fedorov Ukrainian Book Chamber " Reviews of professional associations / employers: I. Shevchenko, President of Ukrainian Library Association, Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences, Associate Professor, Honored Worker of Ukraine, Director of the continuous Cultural and Artistic Education of the National Academy of Culture and Arts The Educational Programme has been introduced since 2017. The term for reviewing the educational program is once every 2 years. -

1 Second Field School in Ivano-Frankivsk

Second Field School in Ivano-Frankivsk REPORT: The Second Field School Ivano-Frankivsk Region, Ukraine July 21-August 10, 2010 Prepared by Dr. Maria Kaspina, Dr. Boris Khaimovich & Dr. Vladimir Levin Not a single taxi driver in Ivano-Frankivsk knows where the synagogue is located, although its massive building stands only 50 meters away from the central square bustling with people at its shops and restaurants. The once vibrant Jewish community of Eastern Galicia, numbering half a million people, was not only eradicated by the Nazis and their supporters during the Holocaust, but it has also faded from the memory of local inhabitants. The aim of our field school and the entire Jewish History in Galicia and Bukovina project is to document, collect and revive remnants - physical as well as intangible - that can still be recorded, preserved and revived after 65 years of Jewish absence from the region. Towards this aim, the Second Field School arrived at Ivano-Frankivsk (formerly Stanisławów) during the summer of 2010. The Second Field School in the Ivano-Frankivsk Region took place from July 21 to August 10, 2010. It was organized by the Jewish History in Galicia and Bukovina project and the Moscow 1 Center for University Teaching of Jewish Civilization Sefer. Fifteen students under the guidance of five scholars engaged in the documentation of Jewish history. The school was composed of three teams: one documenting Jewish cemeteries, another recording oral history and ethnographical materials from the local residents and the third team surveying towns and villages in the region. The complex approach applied towards the remnants of Jewish history allows for exploration in the fullest possible way. -

Investment-Passport-NEW-En.Pdf

2000 кm Рига Latvia Sweden Denmark Lithuania Gdansk Russia Netherlands Belarus 1000 кm Rotterdam Poland Belgium Germany Kyiv 500 кm Czech Republic DOLYNA Ukraine France Slovakia Ivano- Frankivsk region Switzerland Austria Moldova Hungary Slovenia Romania Croatia Bosnia and Herzegovina Serbia Italy Varna Montenegro Kosovo Bulgaria Macedonia Albania Turkey Community’s location Area of the community Dolyna district, 351.984 km2 Ivano-Frankivsk region, UkraineGreece Population Administrative center 49.2 thousand people Dolyna Area of agricultural land Community’s constituents 16.1 thousand ha Dolyna and 21 villages Natural resources Established on Oil, gas, salt June 30, 2019 Distance from Dolyna Nearest border International airports: to large cities: crossing points: Ivano-Frankivsk ІIvano-Frankivsk – 58 km Mostyska, Airport – 58 km Lviv region – 138 km Lviv – 110 km Danylo Halytskyi Shehyni, Airport Lviv – 114 km Kyiv – 635 km Lviv region – 151 km Boryspil Rava-Ruska, Airport Kyiv – 684 km Lviv region – 174 km Geography, nature, climate and resources Dolyna, the administrative center of Dolyna Map of Dolyna Amalgamated Territorial Community, is situ- Amalgamated Territorial Community ated in the north east of the district at the intersection of vital transport corridors linking different regions of Ukraine and connecting it to European countries. CLIMATE The climate is temperate continental and humid, with cool summers and mild winters. The frost-free period lasts an average of 155– 160 days, and the vegetation period is 205–215 days. Spring frost bites usually cease in the last third of April. Autumn frost bites arrive in the last third of September. HUMAN RESOURCES WATER RESOURCES The total number of working age population is 29.5 thousand. -

Building a Spatial Information System to Support the Development of Agriculture in Poland and Ukraine

agronomy Article Building a Spatial Information System to Support the Development of Agriculture in Poland and Ukraine Beata Szafranska 1, Malgorzata Busko 2,* , Oleksandra Kovalyshyn 3 and Pavlo Kolodiy 4 1 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, Marshal’s Office of the Malopolska Voivodeship, 30017 Krakow, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Integrated Geodesy and Cartography, AGH University of Science and Technology, Al. Mickiewicza 30, 30059 Krakow, Poland 3 Department of Land Cadaster, Faculty of Land Management, Lviv National Agrarian University, 80381 Dubliany, Ukraine; [email protected] 4 Department of Geodesy and Geoinformatics, Land Management Faculty, Lviv National Agrarian University, 80381 Dubliany, Ukraine; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-12-6174122 Received: 28 October 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: The space of rural areas is subject to constant changes in terms of structure and development. The area structure of rural areas, especially in the south and east of Poland, remains unsatisfactory. The weakness of Polish agriculture is the fragmentation of the area structure of its farms; this was due to historical, natural, economic and social factors and, to a large extent, tradition. Therefore, the current status of agricultural land in Poland requires carrying out many arrangement and agricultural operations. In Ukraine, there is also no coherent IT system that would allow for the efficient management of rural space and agriculture. In order to conduct a coherent rural development policy in the region, the self-governments in Poland and in Ukraine are facing the need to expand the existing spatial information infrastructure system. -

Full Study (In English)

The Long Shadow of Donbas Reintegrating Veterans and Fostering Social Cohesion in Ukraine By JULIA FRIEDRICH and THERESA LÜTKEFEND Almost 400,000 veterans who fought on the Ukrainian side in Donbas have since STUDY returned to communities all over the country. They are one of the most visible May 2021 representations of the societal changes in Ukraine following the violent conflict in the east of the country. Ukrainian society faces the challenge of making room for these former soldiers and their experiences. At the same time, the Ukrainian government should recognize veterans as an important political stakeholder group. Even though Ukraine is simultaneously struggling with internal reforms and Russian destabilization efforts, political actors in Ukraine need to step up their efforts to formulate and implement a coherent policy on veteran reintegration. The societal stakes are too high to leave the issue unaddressed. gppi.net This study was funded by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Ukraine. The views expressed therein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation. The authors would like to thank several experts and colleagues who shaped this project and supported us along the way. We are indebted to Kateryna Malofieieva for her invaluable expertise, Ukraine-language research and support during the interviews. The team from Razumkov Centre conducted the focus group interviews that added tremendous value to our work. Further, we would like to thank Tobias Schneider for his guidance and support throughout the process. This project would not exist without him. Mathieu Boulègue, Cristina Gherasimov, Andreas Heinemann-Grüder, and Katharine Quinn-Judge took the time to provide their unique insights and offered helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. -

Annual Pro 2 Annual Progress Report 2011 Report

ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT 2011 MUNICIPAL GOVERNANCE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME www.undp.org.ua http://msdp.undp.org.ua UNDP Municipal Governance and Sustainable Development Programme Annual Progress Report 2011 Acknowledgement to Our Partners National Partners Municipality Municipality Municipality Municipality of of Ivano- of Zhytomyr of Rivne Kalynivka Frankivsk Municipality Municipality Municipality Municipality of Novograd- of Galych of Mykolayiv of Saky Volynskiy Municipality Municipality Municipality of Municipality of of Hola of Dzhankoy Kirovske Kagarlyk Prystan’ Municipality of Municipality Municipality of Municipality Voznesensk of Ukrayinka Novovolynsk of Shchelkino Municipality of Municipality Municipality of Municipality Mogyliv- of Lviv Dolyna of Rubizhne Podilskiy Academy of Municipality Municipality of Municipality Municipal of Tulchyn Yevpatoria of Bakhchysaray Management Committee of Settlement Vekhovna Rada on Settlement Settlement of Pervomayske State Construction of Nyzhnegorskiy of Zuya Local Self- Government Ministry of Regional Settlement Development, Settlement Construction, Municipality of of Krasno- of Novoozerne Housing and Vinnytsya gvardiyske Municipal Economy of Ukraine International Partners Acknowledgement to Our Partners The achievements of the project would not have been possible without the assistance and cooperation of the partner municipalities of our Programme, in particular Ivano-Frankivsk, Rivne, Zhytomyr, Galych, Novograd-Volynskiy, Mykolayiv, Kirovske, Hola Prystan’, Kagarlyk, Voznesensk, -

Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University Ogneviuk

Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University ISSUED Administrated by Scientific board of Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University ____ 20__ ______ ., record № ______________ Head of Scientific board, rector Ogneviuk V. O. ____________________________ Education professional programme 291.00.02 Regional studying Department: 29 International relations Speciality: 291 International relations, public communications and regional studying Qualification: bachelor of International relations, public communications and regional studying Implemented from __.__20__ (order of __.__20__ No.____) Kyiv, 2017 APPROVAL FORM of education professional programme The chair of international relations and international law Protocol of March 6, 2017, No. 8 Head of the chair ______________________ Havrylyuk O. V. Academic board of Faculty of law and international relations Protocol of April 18, 2017, No. 7 Head of the academic board________________________ Hrytsiak I. A. Vice-rector on scientific-methodical and academic work __________________ Zhyltsov O. B. Head of scientific and methodological centre of standardization and quality of education __________________ Leontieva O. V. Research laboratory of education internationalization Head ________________ Vyhovska O. S. ____ ___________ 2017 2 Vice-rector of scientific work _______________ Vinnikova N. M. ____ ______ 2017 INTRODUCTION Developed on the basis of Law of Ukraine ‘On Higher Education’ of July 1, 2015 No. 1556 UII based on the Project of Standard for speciality 055 International relations, public communications and regional -

109 Since 1961 Paleocene Deposits of the Ukrainian Carpathians

since 1961 BALTICA Volume 33 Number 2 December 2020: 109–127 https://doi.org/10.5200/baltica.2020.2.1 Paleocene deposits of the Ukrainian Carpathians: geological and petrographic characteristics, reservoir properties Halyna Havryshkiv, Natalia Radkovets Havryshkiv, H., Radkovets, N. 2020. Paleocene deposits of the Ukrainian Carpathians: geological and petrographic char- acteristics, reservoir properties. Baltica, 33 (2), 109–127. Vilnius. ISSN 0067-3064. Manuscript submitted 27 February 2020 / Accepted 10 August 2020 / Published online 03 Novemver 2020 © Baltica 2020 Abstract. The Paleocene Yamna Formation represents one of the main oil-bearing sequences in the Ukrai- nian part of the Carpathian petroleum province. Major oil accumulations occur in the Boryslav-Pokuttya and Skyba Units of the Ukrainian Carpathians. In the great part of the study area, the Yamna Formation is made up of thick turbiditic sandstone layers functioning as reservoir rocks for oil and gas. The reconstructions of depositional environments of the Paleocene flysch deposits performed based on well log data, lithological and petrographic investigations showed that the terrigenous material was supplied into the sedimentary basin from two sources. One of them was located in the northwest of the study area and was characterized by the predomi- nance of coarse-grained sandy sediments. Debris coming from the source located in its central part showed the predominance of clay muds and fine-grained psammitic material. The peculiarities of the terrigenous material distribution in the Paleocene sequence allowed singling out four areas with the maximum development (> 50% of the total section) of sandstones, siltstones and mudstones. The performed petrographic investigations and the estimation of reservoir properties of the Yamna Formation rocks in these four areas allowed establishing priority directions of further exploration works for hydrocarbons in the study territory. -

Analiza Și Evaluarea Potențialului De Investiții În Regiunea Orientali

Programul de Cooperare Transfrontalierǎ ENPI Programul este cofinanţat Ungaria-Slovacia-România-Ucraina de către Uniunea Europeană Proiectul “Promovarea oportunităților de Uniunea Europeană este constituită din 28 investiții, cooperarea între întreprinderile mici și mijlocii de state membre care au decis să își unească treptat și dezvoltarea relațiilor transfrontaliere în Regiunea cunoștințele, resursele și destinele. Împreună, pe Carpatică” este implementat în cadrul Programului parcursul unei perioade de extindere de 50 de ani, ele de Cooperare Transfrontalieră Ungaria-Slovacia- au creat o zonă de dezvoltare, stabilitate, democrație România-Ucraina ENPI 2007-2013 (www.huskroua- și dezvoltare durabilă, menținând diversitatea culturală, ANALIZA ȘI EVALUAREA cbc.net) și este cofinanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin toleranța și libertățile individuale. Instrumentul European de Vecinătate și Parteneriat. Uniunea Europeană este decisă să împărtășească POTENȚIALULUI DE INVESTIȚII Obiectivul general al programului este realizările și valorile sale cu țările și popoarele de dincolo intensificarea și adâncirea cooperării de o manieră de granițele sale. durabilă din punct de vedere social, economic și Comisia Europeană este organul executiv al al mediului, între regiuni din Ucraina (Zakarpatska, Uniunii Europene. ÎN REGIUNEA CARPATICĂ Ivano-Frankivska și Chernivetska) și zonele eligibile și adiacente din Ungaria, România și Slovacia. “Această publicație a fost realizată în cadrul proiectului “Promovarea oportunităților de investiții, cooperarea între