Східноєвропейський Історичний Вісник East European Historical Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

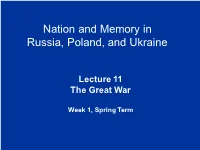

Nation and Memory in Russia, Poland, and Ukraine

Nation and Memory in Russia, Poland, and Ukraine Lecture 11 The Great War Week 1, Spring Term Outline 1. National concepts and war aims 2. Galicia: Atrocities, occupation, reconquest 3. The February Revolution 4. Outlook Putzger, Historischer Weltatlas, pp. 106-107 Pavel Miliukov, leader of the liberal party (Kadets) Russian Concepts 1914 Tsar and supporter of Society autocracy • Strengthening of the authority Constitutional reforms, of the Tsar participation of society • Territorial gains in West and Territorial gains in West and South (Constantinople) South (Constantinople) • Defeat of Germany and Austria Defeat of Germany and Austria • Occupation of East Galicia and Occupation of East Galicia and Bukowina – Liberation of Bukowina – Liberation of Russian (East Slavic – Russian (East Slavic – Ruthenian) population Ruthenian) population • To win the support of the Poles To win the support of the Poles – – Promise of autonomy of Promise of autonomy of unified unified ethnic Polish territory ethnic Polish territory under under tsarist rule tsarist rule Józef Piłsudski Roman Dmowski Polish Concepts 1914 Piłsudski Dmowski • Independence • Autonomy of a unified Poland under tsa • Together with Austria and • Together with Russia Germany • Federation of Poland with • Polish nation state, Ukraine, Lithuania etc., exclusive, mainly Polish inclusive Catholics • Rights of minorities • Assimilationist • Jagiellonian Poland – • “Piast Poland” – territory territory in the East in the West • Enemy No. 1: Russia • Enemy No. 1: Germany Ukrainian Concepts 1914 Russian Ukraine East Galicia • Defeat of Austria • Defeat of Russia • Autonomy of ethnic • Autonomy (Ukrainian Ukrainian territory in a Crownland) in Austria, constitutional or partition of Galicia democratic Russia and Lodomeria • Unification of Ukraine • Unification of Ukraine under Austrian under Tsar Emperor Outline 1. -

Influence of Agglomerations on the Development of Tourism in the Lviv Region

Studia Periegetica nr 3(27)/2019 DOI: 10.26349/st.per.0027.03 HALYNA LABINSKA* Influence of Agglomerations on the Development of Tourism in the Lviv Region Abstract. The author proposes a method of studying the influence of agglomerations on the development of tourism. The influence of agglomerations on the development of tourism is -il lustrated by the case of the Lviv region and the use of correlation analysis. In addition, official statistics about the main indicator of the tourism industry by region and city are subjected to centrographic analysis. The coincidence of weight centers confirms the exceptional influence of the Lviv agglomeration on the development of tourism in the region, which is illustrated with a cartographic visualization. Keywords: agglomeration, tourism, research methodology 1. Introduction Urbanization, as a complex social process, affects all aspects of society. The role of cities, especially large cities, in the life of Ukraine and its regions will only grow. The growing influence of cities on people’s lives and their activities was noted in the early 20th century by the professor V. Kubiyovych [1927]. Mochnachuk and Shypovych identified three stages of urbanization in Ukraine during the second half of the 20th century: 1) urbanization as a process of urban growth; 2) suburbanization – erosion of urban nuclei, formation of ag- glomerations; 3) rurbanization – urbanization of rural settlements within urban- ized areas [Mochnachuk, Shypovych 1972: 41-48]. The stage of rurbanization is ** Ivan Franko National University of Lviv (Ukraine), Department of Geography of Ukraine, e-mail: [email protected], orcid.org/0000-0002-9713-6291. 46 Halyna Labinska consistent with the classic definition of “agglomeration” in the context of Euro- pean urbanism: a system that includes the city and its environs (Pierre Merlen and Francoise Shoe). -

Pdf) LC/PUB.2017/24-P Distribution: General Copyright © United Nations, December 2017 All Rights Reserved Printed at United Nations, Santiago S.17-00682

Effects of internal migration on the human settlements system in Latin America and the Caribbean Jorge Rodríguez Vignoli 7 Economic growth and income concentration and their effects on poverty in Brazil Jair Andrade Araujo, Emerson Marinho and Guaracyane Lima Campêlo 33 Personal income tax and income inequality in Ecuador between 2007 and 2011 Liliana Cano 55 Analysis of formal-informal transitions in the Ecuadorian labour market Adriana Patricia Vega Núñez 77 The impact on wages, employment and exports of backward linkages between multinational companies and SMEs Juan Carlos Leiva, Ricardo Monge-González and Juan Antonio Rodríguez-Álvarez 97 Job satisfaction in Chile: geographic determinants and differences Luz María Ferrada 125 Currency carry trade and the cost of international reserves in Mexico Carlos A. Rozo and Norma Maldonado 147 The mining canon and the budget political cycle in Peru’s district municipalities, 2002-2011 Carol Pebe, Norally Radas and Javier Torres 167 A structuralist-Keynesian model for determining the optimum real exchange rate for Brazil’s economic development process: 1999-2015 André Nassif, Carmen Feijó and Eliane Araújo 187 Impact of the Guaranteed Health Plan with a single community premium on the demand for private health insurance in Chile Eduardo Bitran, Fabián Duarte, Dalila Fernandes and Marcelo Villena 209 ISSN 0251-2920 Thank you for your interest in this ECLAC publication ECLAC Publications Please register if you would like to receive information on our editorial products and activities. When you register, you may specify your particular areas of interest and you will gain access to our products in other formats. www.cepal.org/en/suscripciones REVIEW ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN NO 123 DECEMBER • 2017 Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Mario Cimoli Deputy Executive Secretary a.i. -

Zitierhinweis Copyright Holubec, Stanislav: Rezension Über: Paul Robert Magocsi, with Their Backs to the Mountains. a History O

Zitierhinweis Holubec, Stanislav: Rezension über: Paul Robert Magocsi, With their Backs to the Mountains. A History of Carpathian Rus´ and Carpatho-Rusyns, Budapest: Central European University Press, 2015, in: Hungarian Historical Review, 2016, 3, S. 713-716, DOI: 10.15463/rec.1929412761, heruntergeladen über recensio.net First published: http://www.hunghist.org/index.php/component/content/artic... copyright Dieser Beitrag kann vom Nutzer zu eigenen nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken heruntergeladen und/oder ausgedruckt werden. Darüber hinaus gehende Nutzungen sind ohne weitere Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber nur im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Schrankenbestimmungen (§§ 44a-63a UrhG) zulässig. BOOK REVIEWS With their Backs to the Mountains: A History of Carpathian Rus´ and Carpatho-Rusyns. By Paul Robert Magocsi. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2015. 550 pp. Paul Robert Magocsi has authored numerous books on the history of Central and Eastern Europe, Ukraine, and particularly the region he calls Carpathian Rus´. In his new book, With their Backs to the Mountains: A History of Carpathian Rus´ and Carpatho-Rusyns, he understands Carpathian Rus´ as a territory inhabited predominantly by a people whom some consider part of the Ukrainian nation, others a distinct ethnographic group within it, while still others, including Magocsi, an entirely separate nation. The belief that Rusyns are an independent nation with a history the roots of which stretch back to the Middle Ages can be seen as the central thesis of the book, which is, like most works that have the character of a textbook, more descriptive than analytical. The territory dominated by this group ranges on both sides of Carpathians from eastern Slovakia to the Ukrainian–Romanian borderland. -

Fun and Games As a Form of Physical Culture in the Traditional Religious and Social Rituals of the Lemkos. the Ethnomethodological Approach

Pol. J. Sport Tourism 2013, 20, 44-50 44 DOI: 10.2478/pjst-2013-0005 FUN AND GAMES AS A FORM OF PHYSICAL CULTURE IN THE TRADITIONAL RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL RITUALS OF THE LEMKOS. THE ETHNOMETHODOLOGICAL APPROACH ERNEST SZUM, RYSZARD CIEŒLIÑSKI The Josef Pilsudski University of Physical Education in Warsaw, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport in Bia³a Podlaska, Department of Pedagogics Mailing address: Ryszard Cieœliñski, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport in Bia³a Podlaska, Department of Pedagogics, 2 Akademicka Street, 21-500 Bia³a Podlaska, tel.: + 48 83 3428776, fax: +48 83 3428800, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article presents the Lemkos games and fun as popular forms of physical culture of the Lemko community living in former areas of south-eastern Poland. It presents them as part of the intangible culture of the vanishing ethnic group. The traditional elements of physical culture of the Lemko community, especially fun and games have been presented on the basis of the general characteristics of this ethnic group, and the entire history of the presence of the Lemkos in Poland. Folk fun and games, as a form of physical activity are presented in the broad sense of physical and cultural system and the Lemko community located within the cultural system. The need for such a study is due to the fact that there are no other ethnological or cultural anthropology studies on physical culture of this ethnic group. Key words: Lemkos, physical culture, fun and games, religious rites, social rituals, leisure sociology, ethnology, cultural anthropology Introduction During the 2011 National Census the Lemko nationality was declared by 10,000 people, compared with the 38.5 million In European culture, traditional games and activities of folk population of Poland, including half of the respondents sur- nature, as well as dances and other forms of physical activity are veyed declaring it as the only nationality, 2,000 people indi- an important component of any national culture [1]. -

Tytuł Artykułu

DOI: 10.21005/pif.2019.38.B-03 ARCHITECTURAL AND URBAN CONTEXT OF INTERNATIONAL AUTOMOBILE CHECK POINTS ON THE WESTERN BORDERS OF UKRAINE ARCHITEKTONICZNY I URBANISTYCZNY KONTEKST MIĘDZYNARODOWYCH PUNKTÓW KONTROLI NA ZACHODNICH GRANICACH UKRAINY Kashuba О. М. Ph.D student ORCID:0000-0003-1181-5320 Katedra Projektowania Architektonicznego National University «Lviv Polytechnic» Institute of Architecture, Department of Design ABSTRACT The architectural and urban features of the existing system of automobile check points (ACP) on the Ukrainian-Polish transboundary territories have been revealed due to re- thinking of European examples in this field and possibilities of practical application of this experience for Ukraine. New structural models of ACP, which take into consideration the differentiation of spaces for various transit traffics, have been proposed. The model of the customs-transport complex crossing point and its typological features have been formu- lated. Key words: international automobile check points, border, architectural and urban fea- tures, transboundary territory, avanzone infrastructure, customs-transport complex on the border. STRESZCZENIE Artykuł opisuje cechy architektoniczne i urbanistyczne istniejącego systemu samochodo- wego punktu kontrolnego (SPK) na ukraińsko-polskich terytoriach transgranicznych. Do- konano analizy europejskich i światowych przykładów podobnych rozwiązań oraz zapro- ponowano możliwość praktycznego zastosowania tego doświadczenia na Ukrainie. Opi- sano nowe modele strukturalne SPK, konieczność zróżnicowania przestrzeni dla różnych tranzytow. Sformułowano model skrzyżowania kompleksu celno-transportowego i jego cechy typologiczne. Słowa kluczowe: architektoniczne i urbanistyczne cechy, infrastruktura predstrefy SPK, kompleks celno-transportowy na granicy,międzynarodowe samochodowe punkty kontrol- ne na graniczy, terytorium transgraniczna. 34 s p a c e & FORM | p r z e s t r z e ń i FORMa ‘38_2019 1. -

Die Historische Straße VIA REGIA in Der Ukraine Von Prof. Dr. L. Voitovych, Direktor Des Instituts Für Mittelalter Und Byzanti

Die historische Straße VIA REGIA in der Ukraine von Prof. Dr. L. Voitovych, Direktor des Instituts für Mittelalter und Byzantinistik an der Lviver Nationaluniversität „Ivan Franko“, führender Wissenschaftler am Institut für Ukrainewissenschaft „Ivan Krypiakevych“ der Nationalen Akademie der Wissenschaften der Ukraine. 1. Die Kiever Rus In Zentral- und Osteuropa, zwischen der Ostsee und dem Schwarzen Meer, dem Dnjestr-, Dnepr - und Okabecken entlang, entstanden vom 7. bis zum 10. Jahrhundert ostslawische Stämme, die sich zu Stam- mesfürstentümern entwickelten: Fürstentümer der Chorvaten (Weiß-Kroaten: Zasyanen, Terebovlyanen, Poboranen), Volynyanen (eigentlich Volynyanen, Buzhanen, Lutschanen, Tschervjanen, Duliben), Drev- lyanen, Poljanen, Siverjanen, Dregovitschen, Krivitschen, Radimitschen, Vjatitschen und Slowenen. Spä- testens 753 legten skandinavische Wikinger ihren Stützpunkt Aldeigjuborg (Staraja Ladoga/ Alt-Ladoga) am Fluss Ladozhka neben seiner Einmündung in den Ladogasee an, der bis zum Ende des 8. Jahrhun- derts das Zentrum eines kleinen Königreiches mit einer gemischten finnisch-slawisch-warägischen Bevöl- kerung wurde. Mit dem Machtantritt Rjuriks aus dem jütländischen Zweig dänischer Skoldungen (Skjölder) wurde Lado- ga das Zentrum der slawischen und umliegenden finnischen Länder (Chud). Im Jahre 882 hat der Nach- folger Rjuriks, Oleg („der Prophet“), Kiev erobert und den Grundstein für die Vereinigung ostslawischer Fürstentümer um die Stadt gelegt, die unter Vladimir Sviatoslavych dem Heiligen (Regierungszeit 980 - 1015) -

UKRAINE the Constitution and Other Laws and Policies Protect Religious

UKRAINE The constitution and other laws and policies protect religious freedom and, in practice, the government generally enforced these protections. The government generally respected religious freedom in law and in practice. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the government during the reporting period. Local officials at times took sides in disputes between religious organizations, and property restitution problems remained; however, the government continued to facilitate the return of some communal properties. There were reports of societal abuses and discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. These included cases of anti-Semitism and anti- Muslim discrimination as well as discrimination against different Christian denominations in different parts of the country and vandalism of religious property. Various religious organizations continued their work to draw the government's attention to their issues, resolve differences between various denominations, and discuss relevant legislation. The U.S. government discusses religious freedom with the government as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. U.S. embassy representatives raised these concerns with government officials and promoted ethnic and religious tolerance through public outreach events. Section I. Religious Demography The country has an area of 233,000 square miles and a population of 45.4 million. The government estimates that there are 33,000 religious organizations representing 55 denominations in the country. According to official government sources, Orthodox Christian organizations make up 52 percent of the country's religious groups. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate (abbreviated as UOC-MP) is the largest group, with significant presence in all regions of the country except for the Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv, and Ternopil oblasts (regions). -

Family Name Files That Can Be Accessed in the Boerne Public Library Local and Family History Archives

FAMILY NAME FILES THAT CAN BE ACCESSED IN THE BOERNE PUBLIC LIBRARY LOCAL AND FAMILY HISTORY ARCHIVES A Abadie, Ables, Abshire Ackerman Adair, Adam, Adamek, Adamietz, Adams, Adamson, Adcock, Adkins, Adler, Adrian, Adriance, Agold, Aguirre, Ahr, Ahrlett, Alba, Albrecht, Albright, Alcorn, Alderman, Aldridge, Alexander, Alf, Alford, Algueseva, Allamon, Allen, Allison, Altgelt, Alvarez, Amason, Ammann, Ames, Anchondo, Anderson, Angell, Angle, Ansaldo, Anstiss, Appelt, Armendarez, Armstrong, Arnold, Arnott, Artz, Ashcroft, Asher, Atencio, Atkinson, Aue, Austin, Aycock, B Backer, Bacon, Bacorn, Bain, Baker, Baldwin, Ball, Balser, Bangert, Bankier, Banks, Bannister, Barbaree, Barker, Barkley, Barnard, Barnes, Barnett, Barnette, Barnhart, Baron, Barrett, Barrington, Barron, Barrows, Barta, Barteau, Bartel, Bartels, Barthlow, Barton, Basham, Bates, Batha, Bauer, Baum, Baumann, Bausch, Baxter, Bayard, Bayless, Baynton, Beagle, Bealor, Beam, Bean, Beardslee, Beasley, Beath, Beatty, Beauford, Beaver, Bechtold, Beck, Becker, Beckett, Beckley, Bedford, Bedgood, Bednar, Bedwell, Beem, Beene, Beer, Begia, Behr, Beissner, Bell, Below, Bemus, Benavides, Bender, Bennack, Benefield, Benner, Bennett, Benson, Bentley, Berger, Bergmann, Berlin, Berline, Bernal, Berne, Bernert, Bernhard, Bernstein, Berry, Besch, Beseler, Beshea, Besser, Best, Bettison, Beutnagel, Bevers, Bey, Beyer, Bickel, Bidus, Bien, Bierman, Bierschwale, Bigger, Biggs, Billingsley, Birdsong, Birkner, Bish, Bitzkie, Black, Blackburn, Blackford, Blackwell, Blair, Blaize, Blake, Blakey, Blalock, -

Ukraine: Travel Advice

Ukraine: Travel Advice WARSZAWA (WARSAW) BELARUS Advise against all travel Shostka RUSSIA See our travel advice before travelling VOLYNSKA OBLAST Kovel Sarny Chernihiv CHERNIHIVSKA OBLAST RIVNENSKA Kyivske Konotop POLAND Volodymyr- OBLAST Vodoskhovyshche Volynskyi Korosten SUMSKA Sumy Lutsk Nizhyn OBLAST Novovolynsk ZHYTOMYRSKA MISTO Rivne OBLAST KYIV Romny Chervonohrad Novohrad- Pryluky Dubno Volynskyi KYIV Okhtyrka (KIEV) Yahotyn Shepetivka Zhytomyr Lviv Kremenets Fastiv D Kharkiv ( ni D pr ni o Lubny Berdychiv ep Kupiansk er LVIVSKA OBLAST KHMELNYTSKA ) Bila OBLAST Koziatyn KYIVSKA Poltava Drohobych Ternopil Tserkva KHARKIVSKA Khmelnytskyi OBLAST POLTAVSKA Starobilsk OBLAST OBLAST Stryi Cherkasy TERNOPILSKA Vinnytsia Kremenchutske LUHANSKA OBLAST OBLAST Vodoskhovyshche Izium SLOVAKIA Kalush Smila Chortkiv Lysychansk Ivano-Frankivsk UKRAINEKremenchuk Lozova Sloviansk CHERKASKA Luhansk Uzhhorod OBLAST IVANO-FRANKIVSKA Kadiivka Kamianets- Uman Kostiantynivka OBLAST Kolomyia Podilskyi VINNYTSKA Oleksandriia Novomoskovsk Mukachevo OBLAST Pavlohrad ZAKARPATSKA OBLAST Horlivka Chernivtsi Mohyliv-Podilskyi KIROVOHRADSKA Kropyvnytskyi Dnipro Khrustalnyi OBLAST Rakhiv CHERNIVETSKA DNIPROPETROVSKA OBLAST HUNGARY OBLAST Donetsk Pervomaisk DONETSKA OBLAST Kryvyi Rih Zaporizhzhia Liubashivka Yuzhnoukrainsk MOLDOVA Nikopol Voznesensk MYKOLAIVSKA Kakhovske ZAPORIZKA ODESKA Vodoskhovyshche OBLAST OBLAST OBLAST Mariupol Berezivka Mykolaiv ROMANIA Melitopol CHIȘINĂU Nova Kakhovka Berdiansk RUSSIA Kherson KHERSONSKA International Boundary Odesa OBLAST -

Human Potential of the Western Ukrainian Borderland

Journal of Geography, Politics and Society 2017, 7(2), 17–23 DOI 10.4467/24512249JG.17.011.6627 HUMAN POTENTIAL OF THE WESTERN UKRAINIAN BORDERLAND Iryna Hudzelyak (1), Iryna Vanda (2) (1) Chair of Economic and Social Geography, Faculty of Geography, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Doroshenka 41, 79000 Lviv, Ukraine, e-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) (2) Chair of Economic and Social Geography, Faculty of Geography, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Doroshenka 41, 79000 Lviv, Ukraine, e-mail: [email protected] Citation Hudzelyak I., Vanda I., 2017, Human potential of the Western Ukrainian borderland, Journal of Geography, Politics and Society, 7(2), 17–23. Abstract This article contains the analysis made with the help of generalized quantative parameters, which shows the tendencies of hu- man potential formation of the Western Ukrainian borderland during 2001–2016. The changes of number of urban and rural population in eighteen borderland rayons in Volyn, Lviv and Zakarpattia oblasts are evaluated. The tendencies of urbanization processes and resettlement of rural population are described. Spatial differences of age structure of urban and rural population are characterized. Key words Western Ukrainian borderland, human potential, population, depopulation, aging of population. 1. Introduction during the period of closed border had more so- cial influence from the West, which formed specific Ukraine has been going through the process of model of demographic behavior and reflected in dif- depopulation for some time; it was caused with ferent features of the human potential. significant reduction in fertility and essential mi- The category of human potential was developed gration losses of reproductive cohorts that lasted in economic science and conceptually was related almost a century. -

Translation Former Policeman Vasyl Pokotylo Is Questioned by Soviet

1 EHRI Online Course in Holocaust Studies USHMM, RG-31.018M, reel 1, copy from HDA SBU, 5-43555, ark. 42–43; 44–53, 79–79zv; 129–129zv. The Holocaust in Ukraine – Auxiliary Administration and Police Translation: C09 Former Policeman Vasyl Pokotylo is questioned by Soviet Interrogators about His Activities in Kiev, is Allowed to Retract Some Statements, and is Sentenced to Death, March– September 1945 [C09-A] QUESTIONNAIRE OF ARRESTEE. 1. Last name: Pokotilo1 2. First name and patronym: Vasilii Fedorovich 3. Year of birth: 1914 4. Place of birth: city of Kyiv, Kyiv Oblast2 5. Place of residence: no fixed place of residence 6. Nationality and citizenship: Ukrainian, citizen of the USSR 7. Passport: n.a. 8. Profession: electrician 9. Occupation: Private of the 239th ARRR3 10. Social background: from a family of clerks 11. Social background: before the revolution: – After the revolution: Worker 12. Education: secondary technical 13. Party membership: no member 14. Military register category: serviceman 15. Service in white and other counterrevolutionary armies: no 16. Participation in gangs and other counterrevolutionary organizations: no 17. Participation in battles with the German-fascist military: participated as member of the [illegible] unit 18. Has been captured or encircled by the enemy: no 19. Family composition: Mother Knei–Pokotilo Efrosin’ia Grigor’evna, residing in the city of Kyiv, at 4 Kudriavs’ka Street, housewife. Wife Pokotilo Anastasiia Ivanovna, born in 1932, residing in the village of Vel’ká-Lomnica (Slovakia), without a fixed occupation. Son Fedor – 2 years old, in the care of his mother. Brothers: Pokotilo Mikhail Fedorovich, born in 1906, residing in the city of Kharkiv, working as [illegible] at the Shevchenko Theater.