Pdf?Sequence=1 [In Ukrainian]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COCKTAIL & BAR LIST Champagne and Wines

COCKTAIL & BAR LIST Champagne and Wines Please ask your waiter to see the full wine list Champagne and Sparkling Glass Bottle Prosecco IGT Veneto, Casa Botter 7.50 28.00 Marie Demets NV 10.00 52.00 Le Mesnil Grand Cru Rose Brut NV 11.50 55.00 Bérèche & Fils NV Brut, Réserve 55.00 Perrier Jouet Grand Brut 60.00 Perrier Jouet Blason Rosé Champagne 85.00 Dom Perignon Vintage 2003 195.00 Krug Grande Cuvée 200.00 White Wine Glass Carafe 500ml Bottle Fontareche 2014 Vin de Pays D'Oc 5.00 15.00 19.00 Viognier 2014 Domaine de Coudoulet 6.50 19.50 24.00 Pinot Grigio Il Palu 2014, Venezia 7.00 21.00 27.00 Sauvignon Blanc, Jules Taylor 2014 NZ 8.50 26.00 33.00 Saint Véran, 2014 Domaine Michel Chavet 8.50 26.00 34.00 Rose Wine Glass Carafe 500ml Bottle Chateau Fontareche 2014 Corbieres 6.00 18.00 24.50 Red Wine Glass Carafe 500ml Bottle Domaine Felines-Jourdan 2014 Grenache/Syrah 5.00 15.00 19.00 Monte Alentejano 2010 Portugal 5.75 18.00 22.50 Chateau des Antonins 2012 Bordeaux Superieur 7.00 21.00 27.00 Côtes du Rhône 2013 Domaine Saint Gayan 7.50 22.50 30.00 Bourgogne Rouge, 2013 Le Clos, Manciat-Poncet 9.50 28.50 38.00 Some of our drinks may contain Allergens. If you have any allergies or Health Concerns Please notify a member of staff before ordering Beer VODKA Tyskie - 33cl - Lager, 5.6% 3.75 Pszeniczniak - 50cl - Wheat; 5,25% 5.50 Ognisko Flavours Light Lager A classic cloudy Wheat Beer Made with Fresh Fruit, Herbs and Spices Shot £3.75, Carafes 10cl - £14.50, 25cl - £35.00, 50cl- £68.00 Koź lak - 50cl - Dark Bock; 6,6% 5.80 Żywe - 50cl - Lager; -

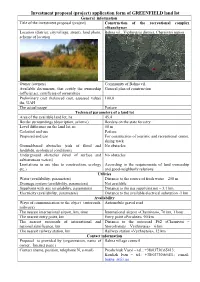

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1981

;?C свОБОДАJLSVOBODA І І і о "в УКРДШСШИИ щоліннмк ^Щ^У UKKAINIAHOAIIV PUBLISHEDrainia BY THE UKRAINIAN NATIONAL ASSOCIATIOnN INC . A FRATERNAWeekL NON-PROFIT ASSOCIATION l ї Ш Ute 25 cents voi LXXXVIII No. 45 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 8, i98i Reagan administration Five years later announces appointment for rights post The Ukrainian Helsinki Group: WASHINGTON - After months of the struggle continues delay, the Reagan administration an– nounced on October 30 that it is no– When the leaders of 35 states gathered in Helsinki in minating Elliot Abrams, a neo-conser– August 1975 signed the Final Act of the Conference on vative Democrat and former Senate Security and Cooperation in Europe, few could aide, to be assistant secretary of state for have foreseen the impact the agreement would have in human rights and humanitarian affairs, the Soviet Union. While the accords granted the Soviets reported The New York Times. de jure recognition of post-World War ll boundaries, they The 33-year-old lawyer, who pre– also extracted some acquiescence to provisions viously worked as special counsel to guaranteeing human rights and freedom, guarantees Sen. Henry Jackson of Washington and that already existed in the Soviet Constitution and Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New countless international covenants. York, joined the administration last At the time, the human-rights provisions seemed January as assistant secretary of state unenforceable, a mere formality, a peripheral issue for international organization affairs. agreed to by a regime with no intention of carrying in announcing the nomination, Presi– them through. dent Ronald Reagan stated that hu– But just over one year later, on November 9,1976,10 man-rights considerations are an im– courageous Ukrainian intellectuals in Kiev moat of portant part of foreign policy, the Times them former political prisoners, formed the Ukrainian said. -

Destroying the National-Spiritual Values of Ukrainians

Historia i Polityka No. 18 (25)/2016, pp. 33–43 ISSN 1899-5160, e-ISSN 2391-7652 www.hip.umk.pl DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/HiP.2016.030 Nadia K indrachuk Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University, Ivano-Frankovsk, Ukraine Destroying the National-Spiritual Values of Ukrainians during the Anti-Religious Offensive of the Soviet Totalitarian State in the 1960s and 1970s Niszczenie wartości narodowo-duchowych Ukraińców podczas anty-religijnej ofensywy sowieckiego państwa totalitarnego w latach 60. i 70. XX wieku • A bst ra kt • • A bst ract • Artykuł zajmuje się kościelnym i religijnym The article deals with the church and religious życiem Ukraińców w kontekście narodowo- life of Ukrainians in the context of national ściowych i politycznych procesów mających and political processes during the 1960s and miejsce w latach 60. i 70. XX wieku. Autorka 1970s. The author characterizes the anti-reli- prezentuje charakterystykę anty-religijnej po- gious policy of the Soviet government, shows lityki rządu radzieckiego, pokazuje jej kierun- its directions, forms, and methods, studies the ki, formy i metody, bada stosunek przedstawi- attitude of Ukraine’s title nation representatives cieli tytularnego narodu wobec prześladowań to religious persecution and to manipulation of religijnych i manipulacji świadomością religij- religious consciousness by the communist lead- ną przez przywódców komunistycznych i pod- ership, and highlights comprehensive atheistic kreśla kompleksowość działań ateizacyjnych activities and the elimination of the ways for i eliminację możliwości odrodzenia religijno- reviving religiosity among people. The author ści wśród ludzi. Autorka odsłania istotę, proces reveals the essence, the process of creating and tworzenia i sztucznego egzekwowania nowego artificially enforcing the new Soviet ritualism radzieckiego rytualizmu w życiu Ukraińców. -

Generate PDF of This Page

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/digital-resources/articles/4397,Battle-of-Warsaw-1920.html 2021-10-01, 13:56 11.08.2020 Battle of Warsaw, 1920 We invite you to read an article by Mirosław Szumiło, D.Sc. on the Battle of Warsaw, 1920. The text is also available in French and Russian (see attached pdf files). The Battle of Warsaw was one of the most important moments of the Polish-Bolshevik war, one of the most decisive events in the history of Poland, Europe and the entire world. However, excluding Poland, this fact is almost completely unknown to the citizens of European countries. This phenomenon was noticed a decade after the battle had taken place by a British diplomat, Lord Edgar Vincent d’Abernon, a direct witness of the events. In his book of 1931 “The Eighteenth Decisive Battle of the World: Warsaw, 1920”, he claimed that in the contemporary history of civilisation there are, in fact, few events of greater importance than the Battle of Warsaw of 1920. There is also no other which has been more overlooked. To better understand the origin and importance of the battle of Warsaw, one needs to become acquainted with a short summary of the Polish-Bolshevik war and, first and foremost, to get to know the goals of both fighting sides. We ought to start with stating the obvious, namely, that the Bolshevik regime, led by Vladimir Lenin, was, from the very beginning, focused on expansion. Prof. Richard Pipes, a prolific American historian, stated: “the Bolsheviks took power not to change Russia, but to use it as a trampoline for world revolution”. -

The Annals of UVAN, Vol . V-VI, 1957, No. 4 (18)

THE ANNALS of the UKRAINIAN ACADEMY of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. V o l . V-VI 1957 No. 4 (18) -1, 2 (19-20) Special Issue A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko Ukrainian Historiography 1917-1956 by Olexander Ohloblyn Published by THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., Inc. New York 1957 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE DMITRY CIZEVSKY Heidelberg University OLEKSANDER GRANOVSKY University of Minnesota ROMAN SMAL STOCKI Marquette University VOLODYMYR P. TIM OSHENKO Stanford University EDITOR MICHAEL VETUKHIV Columbia University The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. are published quarterly by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc. A Special issue will take place of 2 issues. All correspondence, orders, and remittances should be sent to The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. ПУ2 W est 26th Street, New York 10, N . Y. PRICE OF THIS ISSUE: $6.00 ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: $6.00 A special rate is offered to libraries and graduate and undergraduate students in the fields of Slavic studies. Copyright 1957, by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S.} Inc. THE ANNALS OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., INC. S p e c i a l I s s u e CONTENTS Page P r e f a c e .......................................................................................... 9 A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko In tr o d u c tio n ...............................................................................13 Ukrainian Chronicles; Chronicles from XI-XIII Centuries 21 “Lithuanian” or West Rus’ C h ro n ic le s................................31 Synodyky or Pom yannyky..........................................................34 National Movement in XVI-XVII Centuries and the Revival of Historical Tradition in Literature ......................... -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2021

Part 3 of THE YEAR IN REVIEW pages 7-13 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXXIX No. 5 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 31, 2021 $2.00 Ukraine celebrates Unity Day Ukraine’s SBU suspects former agency colonel of plotting to murder one of its generals by Mark Raczkiewycz KYIV – On January 27, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) said it had secured an arrest warrant for Dmytro Neskoromnyi, a former first deputy head of the agency, on suspicion of conspiring to murder a serving SBU general. Mr. Neskoromnyi, a former SBU colonel, allegedly plotted the assassination with currently serving Col. Yuriy Rasiuk of the SBU’s Alpha anti-terrorist unit. The alleged target was 38-year-old Brig. Gen. Andriy Naumov. Mr. Naumov heads the agency’s internal security department, which is responsible for preventing corruption among the SBU’s ranks. RFE/RL In a news release, the SBU provided video RFE/RL A human chain on January 22 links people along the Paton Bridge in Kyiv over the and audio recordings, as well as pictures, as Security Service of Ukraine Brig. Gen. Dnipro River that bisects the Ukrainian capital, symbolizing both sides uniting when evidence of the alleged plot. The former col- Andriy Naumov the Ukrainian National Republic was formed in 1919. onel was allegedly in the process of paying “If there is a crime, we must act on it. $50,000 for carrying out the murder plot. by Roman Tymotsko (UPR), Mykhailo Hrushevskyy. And, in this case, the SBU worked to pre- Mr. -

Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979) Nima Baghdadi Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-22-2018 Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979) Nima Baghdadi Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006552 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baghdadi, Nima, "Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979)" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3652. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3652 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida DYNAMICS OF IRANIAN-SAU DI RELATIONS IN THE P ERSIAN GULF REGIONAL SECURITY COMPLEX (1920-1979) A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Nima Baghdadi 2018 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International Relations and Public Affairs This dissertation, written by Nima Baghdadi, and entitled Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979), having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. __________________________________ Ralph S. Clem __________________________________ Harry D. -

Annual Progress Performance Report

Decentralization Offering Better Results and Efficiency (DOBRE) Annual Progress Performance Report Decentralization Offering Better Results and Efficiency (DOBRE) FY 2018 PROGRESS REPORT 01 October 2017 – 30 September 2018 Award No: AID-121-A-16-00007 Prepared for USAID/Ukraine C/O American Embassy 4 Igor Sikorsky St., Kyiv, Ukraine 04112 Prepared by: Barry Reed, Chief of Party Global Communities 8601 Georgia Avenue Suite 300 Silver Spring, MD 20910, USA Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 2 CONTEXT UPDATE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 KEY NARRATIVE ACHIEVEMENT 11 PROGRESS AGAINST TARGETS 46 PERFORMANCE MONITORING 70 LESSONS LEARNED 72 ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING 72 PROGRESS ON LINKS TO OTHER ACTIVITIES 72 PROGRESS ON LINKS TO HOST GOVERNMENT 74 PROGRESS ON INCLUSIVE DEVELOPMENT 74 FINANCIAL INFORMATION (Required for Contracts Only) 75 SUB-AWARD DETAILS 75 ACTIVITY ADMINISTRATION 76 ATTACHMENTS 78 1 I. ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AOR Agreement Officer’s Representative API Access to public information ARC© Appreciative Review of Capacity [Global Communities] AUC Association of Ukrainian Cities CBO Community-based organization CC Consolidated community CEP Community Engagement Program CEPPS Consortium for Elections and Political Processes COP Chief of Party CSO Civil society organization DESPRO Decentralization Support in Ukraine Project DIALOGUE Development Initiative for Advocating Local Governance in Ukraine DOBRE Decentralization Offering Better Results and Efficiency ER Expected Result EU European Union FRDL Foundation in Support of Local -

Things Borshch!

All Things Baba! All Things Borshch! Lamont County invites you to the 3rd annual Babas & Borshch Ukrainian Festival for a celebration of all things Baba, all things Borshch! For a detailed schedule of activities please check pgs 10-13. Expect to see festival favourites repeated: Ukrainian food concessions, Outdoor Music Jam, Baba's Bazaar, Beer Garden, demonstrations and talks, singers and dancers, passport office, kids' activities, and tours of the church, museum, and grain elevator. Expect many all-new additions: The Baba Magda Fan Club (pg 4) and a FREE borshch sample for everyone (pg 5)! On Saturday catch Michael Mucz, best-selling author of Baba's Kitchen Medicines and welcome the Touring Tin car club as they show off some iron. Get started on your own Kapusta in hands-on sessions. Join us for the Borshch Cook Off on Sunday followed by a screening of James Motluk's documentary A Place Called Shandro as we close out the festival. A huge Dyakuyu to our visitors, sponsors, volunteers, performers, partners, media, individuals, and businesses for supporting the Ukrainian culture and proving that small town Alberta knows how to party! Hazel Anaka, Festival Coordinator 3 All Things Baba! Join the BABA MAGDA FAN CLUB today for giveaways, advance notice of special events, and a chance to win a PRIZE PACK valued at $245! In addition, the first 100 members to sign up online will have a Gift Bag waiting for pick up at the Festival Information Table. Pyrogy Dance Lessons Be sure to join Baba Magda in front of the Outdoor Music Jam stage at 1 pm on Saturday and 12:30 pm on Sunday for a group dance lesson! Music and lyrics courtesy of Winnipeg's Nester Shydlowsky and the Ukrainian Old Timers. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Major-Brands-Price-Book Jan-2020.Pdf

January 2020 MB - EAST MO License # 178674 Table of Contents Spirits Non-potable ..................................................................................59 Eisbock ..................................................................................166 Vodka ..................................................................................3 Potable ..................................................................................59 Kellerbier/Zwickelbier ..................................................................................166 Vodka ..................................................................................3 Specialty Spirits ..................................................................................59 Light ..................................................................................166 Flavored Vodka ..................................................................................7 Aquavit ..................................................................................59 Maibock/Helles Bock ..................................................................................167 Gin ..................................................................................14 Arrack ..................................................................................59 Oktoberfest/Märzen ..................................................................................167 London Dry ..................................................................................14 Neutral Spirit ..................................................................................59