Aaic I Ji 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 8-12, 2022 Sapporo, Japan

IMPORTANT DATES VENUE Abstract submission April 30, 2022 The conference of Biomaterials International 2022 Early registration May 31, 2022 will be held at the Hokkaido University Conference date August 8-12, 2022 Conference Hall. SAPPORO Sapporo is the fifth largest city of Japan by population, with a population of nearly two million, and the largest city on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido. It is the capital city of Hokkaido Prefecture and Ishikari Subprefecture. Sapporo is an ordinance -designated city, and is well known for its functional grid of streets and avenues. Sapporo is also the political and economic center of Hokkaido. It is a tourist city with rich resources, beautiful scenery and four distinct seasons: blooming spring, tree-lined summer, colorful autumn and snowy winter. Sapporo was once rated as the No 1 in “Japan charming city ranking” for three years consecutively. CALL FOR PAPERS Abstracts are invited on the symposia topics or other related areas of biomaterials. Short abstract of approximately 200 words and a two-page extended abstract should be submitted on-line before April 30, 2022. For further information, please visit http://www.biomaterials.tw Organized by: August 8-12, 2022 Sapporo, Japan http://www.biomaterials.tw INVITATION ORGANIZING COMMITTEE REGISTRATION The Biomaterials International 2022 will take Chairman: S.J. Liu (Chang Gung University) Late Early Registration place at the Hokkaido University Conference Co-Chairman: T. Hanawa (Tokyo Medical and Registration Registration (before May 31, Hall, Sapporo, Japan. The conference will bring Dental University) Type (after June 1, 2022) together the international research Secretary: D.M. -

China Versus Vietnam: an Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

A CNA Occasional Paper China versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Distribution unlimited. for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA FOREWORD This legal analysis was commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. policy options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, USN, Judge Advocate Corps (ret.),1 the author of this analysis, is to provide U.S. -

Chapter 6 – Stakeholder

4115, rue Sherbrooke ouest, bureau 310 Westmount, Québec H3Z 1K9 Tel.: 514.481.3401 Fax: 514.481.4679 eem.ca Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of the CBG Mine Extension Project Chapter 6 – Stakeholder consultation DECEMBER 2014 ENGLISH TRANSLATION JUNE 2015 PROJECT NUMBER: 13EAO039 PREPARED FOR: Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinée CBG Mine Extension Project: Chapter 6 – Stakeholder consultation MASTER TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 – BACKGROUND................................................1-1 CHAPTER 2 – PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT STUDY...................2-1 CHAPTER 3 – BIOLOGICAL BASELINE STUDY...................... 3-1 CHAPTER 4 – BIOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT................4-1 CHAPTER 5 – SOCIOECONOMIC BASELINE STUDY ..............5-1 CHAPTER 6 – STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION……………...... 6-1 CHAPTER 7 – SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT....................... 7-1 CHAPTER 8 – REPORT ON POTENTIAL IMPACTS ON HUMAN RIGHTS..............................................8-1 CHAPTER 9 – CUMULATIVE IMPACT ASSESSMENT...............9-1 CHAPTER 10 – ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN...........................................10-1 6-i CBG Mine Extension Project: Chapter 6 – Stakeholder consultation TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 CHAPTER 6 – STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION ............. 6-1 6.1 Consultation methodology ........................................................... 6-1 6.1.1 Scoping mission/Stakeholder engagement plan ............................ 6-2 6.1.1.1 Scoping mission ............................................................. 6-2 6.1.1.2 Stakeholder engagement -

Mapping the Third Republic: a Geographic Information System of France (1870–1940)

HISTORICAL METHODS: A JOURNAL OF QUANTITATIVE AND INTERDISCIPLINARY HISTORY https://doi.org/10.1080/01615440.2021.1937421 Mapping the Third Republic: A Geographic Information System of France (1870–1940) Victor Gay Toulouse School of Economics (TSE) and Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse (IAST), University of Toulouse Capitole, Toulouse, France ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article describes a comprehensive geographic information system of Third Republic Historical GIS; administrative France: the TRF-GIS. It provides annual nomenclatures and shapefiles of administrative con- boundaries; nomenclatures; stituencies of metropolitan France from 1870 to 1940, encompassing general administrative toponyms; France; Third Republic constituencies (departements, arrondissements, cantons) as well as the most significant spe- cial administrative constituencies: military, judicial and penitentiary, electoral, academic, JEL CODES labor inspection, and ecclesiastical constituencies. It further proposes annual nomenclatures N01; N43; N44; N93; at the contemporaneous commune level that map each municipality into its corresponding N94; Y91 administrative framework along with its population count. The 901 nomenclatures, 830 shapefiles, and complete reproduction material of the TRF-GIS are available at https://data- verse.harvard.edu/dataverse/TRF-GIS. 1. Introduction documents (e.g., Ostafin et al. 2020) suggest that this trend will likely intensify in the future. For the seven decades between the collapse of the But a fundamental element empirical researchers Second Empire in 1870 and the establishment of the typically need in order to process, map, and analyze Vichy Regime in 1940, France remained under a sin- spatially localized historical data is an underlying geo- gle political regime: the Third Republic. Despite the graphic frame of reference—a geographic information unprecedented stability of its institutions, France system (GIS). -

A Case Study of Hyogo Prefecture in Japan

ADBI Working Paper Series INDUSTRY FRAGMENTATION AND WASTEWATER EFFICIENCY: A CASE STUDY OF HYOGO PREFECTURE IN JAPAN Takuya Urakami, David S. Saal, and Maria Nieswand No. 1218 February 2021 Asian Development Bank Institute Takuya Urakami is a Professor at the Faculty of Business Administration, Kindai University, Japan. David S. Saal is a Professor at the School of Business and Economics, Loughborough University, United Kingdom. Maria Nieswand is an Assistant Professor at the School of Business and Economics, Loughborough University, United Kingdom. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Urakami, T., D. S. Saal, and M. Nieswand. 2021. Industry Fragmentation and Wastewater Efficiency: A Case Study of Hyogo Prefecture in Japan. ADBI Working Paper 1218. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/industry- fragmentation-wastewater-efficiency-hyogo-japan Please contact the authors for information about this paper. -

Estimation of the Actual Incidence of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Emergent Hotspots: the Example of Hokkaido, Japan During February–March 2020

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Estimation of the Actual Incidence of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Emergent Hotspots: The Example of Hokkaido, Japan during February–March 2020 Andrei R. Akhmetzhanov 1,2 , Kenji Mizumoto 3,4 , Sung-Mok Jung 1,5 , Natalie M. Linton 1,5 , Ryosuke Omori 6 and Hiroshi Nishiura 1,5,7,* 1 Graduate School of Medicine, Hokkaido University, Kita 15 Jo Nishi 7 Chome, Kita-ku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido 060-8638, Japan; [email protected] (A.R.A.); [email protected] (S.-M.J.); [email protected] (N.M.L.) 2 Global Health Program, Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, 17 Xu-Zhou Road, Taipei 10055, Taiwan 3 Graduate School of Advanced Integrated Studies in Human Survivability, Kyoto University, Yoshida-Nakaadachi-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan; [email protected] 4 Hakubi Center for Advanced Research, Kyoto University, Yoshidahonmachi, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8306, Japan 5 School of Public Health, Kyoto University, Yoshidakonoe cho, Sakyo ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan 6 Research Center for Zoonosis Control, Hokkaido University, Kita 19 Jo Nishi 10 Chome, Kita-ku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido 001-0019, Japan; [email protected] 7 Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST), Japan Science and Technology Agency, Honcho 4-1-8, Kawaguchi, Saitama 332-0012, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-75-753-4490 Citation: Akhmetzhanov, A.R.; Mizumoto, K.; Jung, S.-M.; Linton, Abstract: Following the first report of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Sapporo city, N.M.; Omori, R.; Nishiura, H. -

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 32: 05 – 11 August 2019 Data As Reported by 17:00;11 August 2019

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 32: 05 – 11 August 2019 Data as reported by 17:00;11 August 2019 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 2 69 56 15 New events Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises Mauritania 1068 0 11 1 1 0 Mali 9 706 51 Niger 23 265 225 Burkina Faso Chad Guinea 46 0 3 349 27 11 2 15 1 1005 11 Cote d’Ivoire Nigeria Sierra léone Benin 501 4 192 1 South Sudan 639 157 58 2 Ethiopia Ghana Central African 7 043 2 919 2 1 255 1 Cameroon 1 0 Liberia 38 3 Republic 2 472 91 1 1 1 667 5 281 2 4 0 30 669 91 398 20 7 5 0 23 0 1 0 Democratic Republic Uganda 1 1 1 120 5 of Congo 1 275 6 3 550 25 391 1 Congo 2 816 1 888 46 1 Legend Kenya 1 986 27 120 635 2 162 Rwanda Measles Humanitarian crisis 11 230 0 74 4 13 743 280 Burundi Hepatitis E 5 732 282 1 855 Monkeypox 53 8 35 0 6 829 6 199 1 Acute watery diarrhoea Lassa fever Tanzania Yellow fever 2 733 58 Cholera Angola 424 8 Dengue fever Comoros cVDPV Typhoid fever 3 127 64 86 0 1 0 45 Anthrax 3 Ebola virus disease Floods Zimbabwe Mozambique Malaria Chikungunya Namibia Mauritius Rubella Rift Valley fever Cases Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever 141 0 Deaths 5 711 48 Drought Countries reported in the document 7 052 8 Leishmaniasis Non WHO African Region N WHO Member States with no reported events W E Suspected Aflatoxicosis 3 0 Lesotho 20 0 South Africa S Graded events † 4 12 2 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 47 22 20 21 Ungraded events ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event 1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Info rmation and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies Contents occurring in the WHO African Region. -

Central African Republic, Cholera Epidemic

ACAPS Briefing Note: Central African Republic, Cholera epidemic Briefing Note – 25 August 2016 Anticipated Between end of July and 21 August, 166 cholera cases including 19 CENTRAL AFRICAN scope and deaths had been reported in Ndjoukou, Damara, and Bangui. There scale is the risk that cholera spreads among IDP sites in Bangui, and to REPUBLIC communities along the Oubangui River in DRC. Cholera epidemic Priorities for Health: 166 cholera cases reported and 19 deaths as of 21 Need for international Not required Low Moderate Significant Major humanitarian August. assistance X intervention WASH: Lack of access to drinking water among communities Very low Low Moderate Significant Major along the Oubangui River. Expected impact X Humanitarian Access by road to some communities along the Oubangui River Crisis overview constraints is very limited due to the ongoing rainy season. Some areas are reportedly only accessible by boat. 166 cholera cases and 19 deaths have been recorded in CAR as of 21 August. The government declared an outbreak on 10 August, although cholera was first detected on The security situation is still volatile in Bangui. 27 July in Mourou-Fleuve village, Ndjoukou subprefecture of Kemo, located along the Oubangui River, 100km from the capital Bangui. The outbreak has since spread to Damara subprefecture (Ombella Mpoko) and to at least four arrondissements in Bangui. Most of the affected are located along the Oubangui River, which serves as the borer with DRC. Road access to these communities is very limited due to the rainy season. Location of reported cholera cases Limitations The number and location of cholera cases in Bangui are not available. -

Apresentação Do Powerpoint

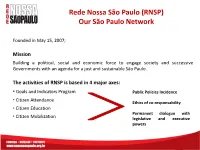

Rede Nossa São Paulo (RNSP) Our São Paulo Network Founded in May 15, 2007; Mission Building a political, social and economic force to engage society and successive Governments with an agenda for a just and sustainable São Paulo. The activities of RNSP is based in 4 major axes: • Goals and Indicators Program Public Policies Incidence • Citizen Attendance Ethics of co-responsability • Citizen Education Permanent dialogue with • Citizen Mobilization legislative and executive powers Rede Nossa São Paulo (RNSP) Our São Paulo Network Working Groups RNSP counts with the participation of 16 thematic working groups. Os GTs compromise representatives of institutions and citizens and fulfill an agenda which is decided collectively on the Network. The groups have autonomy to plan the actions from de perspective of each thematic area. Each GT meeting occurs periodically. GTs: Social Assistance, Culture, Education, Environment, Budget, Work and Income, Monitoring of Municipality Assembly, Child and Teenager, Communication, Participatory Democracy, Sport and Leisure, Indicators, legal, Youth, Urban Mobility and Health. Rede Nossa São Paulo (RNSP) Our São Paulo Network GT GT GT GT GT Inter GTs GT GT Collegiate GT GT Executive Secretariat GT GT GT GT GT Initiatives Our São Paulo Citizen Observatory Virtual data bank that makes available a set of social, environmental, economic, politic and cultural rights indicators about the city of São Paulo, in each of its 31 subprefectures and in the 96 district of the city which will be constantly updated, evaluated and exposed all over the society. The website is being restructured at the moment, so that only the previous platform is available at: www.nossasaopaulo.org.br/observatorio The new platform will have the format and information that is being shown in the next slides. -

3 · Reinterpreting Traditional Chinese Geographical Maps

3 · Reinterpreting Traditional Chinese Geographical Maps CORDELL D. K. YEE My interest in this chapter and the following four is tra frames in mind. These extended inquiries are obtained ditional Chinese geographic mapping-that is, Chinese at some cost, however. With a thematic approach one mapping of the earth before its Westernization in the late risks losing a clear sense of chronology, and one sacrifices nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One of the first the power of narrative to maintain a sense of direction. lessons one learns when studying this subject is that the By keeping the focus on ideas or themes, one also risks traditional periodization used in scholarship is unsatis losing sight of the maps themselves. Detailed descriptions factory. The traditional scheme takes the rise and fall of of artifacts can disrupt the flow of an argument or at least China's ruling houses as constituting distinct periods (see make it harder to follow, and so in the thematic chapters table 2.1). Such a scheme may have been useful for orga that follow this one, artifacts are dealt with in only as nizing material dealing with political and institutional his much detail as is necessary to support the arguments pre tory, and as will be seen in a later chapter, cartography sented. was intimately connected to that history. But carto The loss of chronology and detail would be regret graphic developments do not neatly parallel changes in table, especially when at least part of the audience for politics. Historians of cartography in the past, however, this book-collectors and cartobibliographers, for exam have tried to tie cartography to dynastic changes in ways ple-could reasonably be expected to take an interest in I have found misleading. -

Pdf | 281.89 Kb

Special Report— March 31, 2000 FEWS bulletin 1999/2000 Sahel VulnerabilityAFR/00-03 Assessment USAID-Financed Famine Early Warning System Eastern Africa and the Horn Inside: The Current Crisis Worsens in Ethiopia New assessments in Somalia target extremely food-insecure areas ................. 1 (Insert) Food aid needed in Tanzania but need t the time of this report,the onset of the criti- If the belg harvest fails completely,the dimen- estimates lowered ................................. 3 Acal belg (secondary) rains was already 3 to 5 sions of the crisis will expand quickly.Early analy- Distribution activities continue in Karamoja weeks late in highly and extremely food-insecure ses of the potential impact of a total failure of the Area and Bundibugyo District in Uganda .... 3 agricultural areas in Tigray,Amhara,Oromiya and belg harvest suggest that food aid requirements NGOs withdraw from southern Sudan over SNNPR Regions.The second half of March is the during 2000 could rise from 836,000 MT to almost Memo of Understanding issue ................ 4 last viable planting period for farmers to plant 1.3 million MT.In the northern highlands (South Current food access conditions generally good short-cycle belg crops.Large tracts of parched pas- Tigray,North Wello,South Wello and North Shewa), in Mauritania,but food insecurity toral areas in the SNNPR,Oromiya and Somali Re- about 2 million people are highly dependent on looms for some .................................... 4 gions continued,literally,to burn under extended the belg-season harvest of short-cycle crops.A har- Abundance brings low cereal prices and dryness.If the belg rains do finally come in late vest failure would mean that most of these farm- hardship for some Malians .................... -

The Example of Hokkaido, Japan During February–March 2020 Andrei R

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.24.20077800; this version posted May 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY 4.0 International license . Estimation of the actual incidence of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in emergent hotspots: The example of Hokkaido, Japan during February–March 2020 Andrei R. Akhmetzhanov1;2, Kenji Mizumoto1;3;4, Sung-mok Jung1;2, Natalie M. Linton1;2, Ryosuke Omori1;5, Hiroshi Nishiura1;2;6;∗ 1Cluster Intervention Group, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, Japan 2Graduate School of Medicine, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan 3Graduate School of Advanced Integrated Studies in Human Survivability, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan 4Hakubi Center for Advanced Research, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan 5Research Center for Zoonosis Control, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan 6CREST, Japan Science and Technology Agency, Honcho 4-1-8, Kawaguchi, Saitama 332-0012, Japan ∗ Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-11-706-5066 Abstract Following the first report of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Sapporo City, Hokkaido Prefecture, Japan on 14 February 2020, a surge of cases was observed in Hokkaido during February and March. As of 6 March, 90 cases were diagnosed in Hokkaido. Unfortunately, many infected persons may not have been recognized as cases due to having mild or no symptoms. We therefore estimated the actual number of COVID-19 cases in (i) Hokkaido Prefecture and (ii) Sapporo City using data on cases diagnosed outside these areas.