Central African Republic, Cholera Epidemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central-African-Republic-COVID-19

Central African Republic Coronavirus (COVID-19) Situation Report n°7 Reporting Period: 1-15 July 2020 © UNICEFCAR/2020/A.JONNAERT HIGHLIGHTS As of 15 July, the Central African Republic (CAR) has registered 4,362 confirmed cases of COVID-19 within its borders - 87% of which are local Situation in Numbers transmissions. 53 deaths have been reported. 4,362 COVID-19 In this reporting period results achieved by UNICEF and partners include: confirmed cases* • Water supplied to 4,000 people in neighbourhoods experiencing acute 53 COVID-19 deaths* shortages in Bangui; *WHO/MoHP, 15 July 2020 • 225 handwashing facilities set up in Kaga Bandoro, Sibut, Bouar and Nana Bakassa for an estimate of 45,000 users per day; 1.37 million • 126 schools in Mambere Kadei, 87 in Nana-Mambere and 7 in Ouaka estimate number of prefectures equipped with handwashing stations to ensure safe back to children affected by school to final year students; school closures • 9,750 children following lessons on the radio; • 3,099 patients, including 2,045 children under 5 received free essential million care; US$ 29.5 funding required • 11,189 children aged 6-59 months admitted for treatment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) across the country; UNICEF CAR’s • 1,071 children and community members received psychosocial support. COVID-19 Appeal US$ 26 million Situation Overview & Humanitarian Needs As of 15 July, the Central African Republic (CAR) has registered 4,362 confirmed cases of COVID-19 within its borders - which 87% of which are local transmissions. 53 deaths have been reported. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a decrease in number of new cases does not mean an improvement in the epidemiological situation. -

Security Council Distr.: General 13 April 2015

United Nations S/2015/248 Security Council Distr.: General 13 April 2015 Original: English Letter dated 10 April 2015 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to transmit herewith a note verbale from the Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations dated 31 March 2015 and a report on the activities of Operation Sangaris in the Central African Republic, for transmittal to the Security Council in accordance with its resolution 2149 (2014) (see annex). (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 15-05794 (E) 130415 130415 *1505794* S/2015/248 Annex [Original: French] The Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations presents its compliments to the Office of the Secretary-General, United Nations Secretariat, and has the honour to inform it of the following: pursuant to paragraph 47 of Security Council resolution 2149 (2014), the Permanent Mission of France transmits herewith the report on the actions undertaken by French forces from 15 November 2014 to 15 March 2015 in support of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) (see enclosure). The Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations would be grateful if the United Nations Secretariat would bring this report to the attention of the members of the Security Council. 2/5 15-05794 S/2015/248 Enclosure Operation Sangaris Support to the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic in the discharge of its mandate Period under review: -

August 8-12, 2022 Sapporo, Japan

IMPORTANT DATES VENUE Abstract submission April 30, 2022 The conference of Biomaterials International 2022 Early registration May 31, 2022 will be held at the Hokkaido University Conference date August 8-12, 2022 Conference Hall. SAPPORO Sapporo is the fifth largest city of Japan by population, with a population of nearly two million, and the largest city on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido. It is the capital city of Hokkaido Prefecture and Ishikari Subprefecture. Sapporo is an ordinance -designated city, and is well known for its functional grid of streets and avenues. Sapporo is also the political and economic center of Hokkaido. It is a tourist city with rich resources, beautiful scenery and four distinct seasons: blooming spring, tree-lined summer, colorful autumn and snowy winter. Sapporo was once rated as the No 1 in “Japan charming city ranking” for three years consecutively. CALL FOR PAPERS Abstracts are invited on the symposia topics or other related areas of biomaterials. Short abstract of approximately 200 words and a two-page extended abstract should be submitted on-line before April 30, 2022. For further information, please visit http://www.biomaterials.tw Organized by: August 8-12, 2022 Sapporo, Japan http://www.biomaterials.tw INVITATION ORGANIZING COMMITTEE REGISTRATION The Biomaterials International 2022 will take Chairman: S.J. Liu (Chang Gung University) Late Early Registration place at the Hokkaido University Conference Co-Chairman: T. Hanawa (Tokyo Medical and Registration Registration (before May 31, Hall, Sapporo, Japan. The conference will bring Dental University) Type (after June 1, 2022) together the international research Secretary: D.M. -

RAPPORT MENSUEL DE MONITORING DE PROTECTION Chiffres Clés RÉSUMÉ EXÉCUTIF

RAPPORT MENSUEL DE MONITORING DE PROTECTION Nana-Gribizi, Kémo, Bamingui-Bangoran, Ouham | Novembre 2019 Chiffres clés RÉSUMÉ EXÉCUTIF 138 incidents de protection Incidents de protection 138 victimes 110 Rapatriés spontanés enregistrés 138 incidents de protection ont été collectés et enregistrés : - Nana-Gribizi : 36 incidents ; - Bamingui-Bangoran : 50 incidents ; Désagrégation des victimes - Ouham : 30 incidents ; et - Kémo : 22. 150 138 Parmi les incidents rapportés, on compte 58 cas de VBG, 33 cas de violation des droits à 100 la vie et à l’intégrité physique, 31 cas de violation des droits de propriétés, 12 cas de 50 54 59 violation des libertés fondamentales et 04 cas de violations de type 1612 ont été rapportés. Une légère baisse 3,5% d’incidents est constatée par rapport au mois d’octobre 13 12 0 2019. Mission de monitoring 07 missions de monitoring ont été réalisées dans la zone de couverture : Total respectivement 02 dans la Bamingui-Bangoran ; 02 dans la Kémo ; 02 dans la Nana- Gribizi ; et 01 dans l’Ouham. Statut des victimes Difficultés majeures rencontrées dans l’accès aux populations/zones : La dégradation avancée des routes et l’insécurité dans certaines zones constituent des difficultés d’accès aux bénéficiaires. Total 138 Mouvements de population Rapatri… 5 → La mise à jour du mois d’octobre fait état d’un total de 64,855 PDIs sur les sites de la Résident 92 zone : 21,984 PDIs à Kaga-Bandoro ; 4,763 PDI à Ndele et 38,108 PDIs à Batangafo. Retourné 12 → Mouvement de retour : 26 ménages (110 personnes) de rapatriés spontanés ont été enregistrés. -

A Game of Stones

A GAME OF STONES While the international community is working with CAR’s government and diamond companies to establish legitimate supply chains; smugglers and traders are thriving in the parallel black market. JUNE 2017 CAPTURE ON THE NILE 1 For those fainter of heart, a different dealer offers an Pitching for business alternative. “If you want to order some diamonds,” he says, we “will send people on motorcycles to, for Over a crackly mobile phone somewhere in the Central example, Berberati [in CAR] to pick up the diamonds African Republic (CAR), or maybe Cameroon, a dealer and deliver them to you [in Cameroon].”5 As another is pitching for business. “Yes, it’s scary,” he says, “but trader puts it, “we don’t even need to move an inch!”6 in this business, (…) you have to dare.” The business is diamonds and, as he reminds us, “this [CAR] is a If diamond smuggling takes a bit of courage, it also diamond country.”1 takes a head for logistics. The dealer knows his audience. He is speaking to an opportunist. Where others see conflict, instability, and chaos, he sees a business opportunity. Young, ambitious, and “If you come, you are going to see stones. Maybe if you are lucky, a stone will catch your eye” another dealer connected beckons.2 All that remains is to find a way to move the A game is playing out over the future of CAR’s diamonds. valuable stones out of the war-stricken country. While armed groups and unscrupulous international traders eye a quick profit or the means to buy guns To do so, he needs help. -

OCHA CAR Snapshot Incident

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Overview of incidents affecting humanitarian workers January - May 2021 CONTEXT Incidents from The Central African Republic is one of the most dangerous places for humanitarian personnel with 229 1 January to 31 May 2021 incidents affecting humanitarian workers in the first five months of 2021 compared to 154 during the same period in 2020. The civilian population bears the brunt of the prolonged tensions and increased armed violence in several parts of the country. 229 BiBiraorao 124 As for the month of May 2021, the number of incidents affecting humanitarian workers has decreased (27 incidents against 34 in April and 53 in March). However, high levels of insecurity continue to hinder NdéléNdélé humanitarian access in several prefectures such as Nana-Mambéré, Ouham-Pendé, Basse-Kotto and 13 Ouaka. The prefectures of Haute-Kotto (6 incidents), Bangui (4 incidents), and Mbomou (4 incidents) Markounda Kabo Bamingui were the most affected this month. Bamingui 31 5 Kaga-Kaga- 2 Batangafo Bandoro 3 Paoua Batangafo Bandoro Theft, robbery, looting, threats, and assaults accounted for almost 60% of the incidents (16 out of 27), 2 7 1 8 1 2950 BriaBria Bocaranga 5Mbrès Djéma while the 40% were interferences and restrictions. Two humanitarian vehicles were stolen in May in 3 Bakala Ippy 38 2 Bossangoa Bouca 13 Bozoum Bouca Ippy 3 Bozoum Dekoa 1 1 Ndélé and Bangui, while four health structures were targeted for looting or theft. 1 31 2 BabouaBouarBouar 2 4 1 Bossangoa11 2 42 Sibut Grimari Bambari 2 BakoumaBakouma Bambouti -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Central African Republic: Who Has a Sub-Office/Base Where? (05 May 2014)

Central African Republic: Who has a Sub-Office/Base where? (05 May 2014) LEGEND DRC IRC DRC Sub-office or base location Coopi MSF-E SCI MSF-E SUDAN DRC Solidarités ICRC ICDI United Nations Agency PU-AMI MENTOR CRCA TGH DRC LWF Red Cross and Red Crescent MSF-F MENTOR OCHA IMC Movement ICRC Birao CRCA UNHCR ICRC MSF-E CRCA International Non-Governmental OCHA UNICEF Organization (NGO) Sikikédé UNHCR CHAD WFP ACF IMC UNDSS UNDSS Tiringoulou CRS TGH WFP UNFPA ICRC Coopi MFS-H WHO Ouanda-Djallé MSF-H DRC IMC SFCG SOUTH FCA DRC Ndélé IMC SUDAN IRC Sam-Ouandja War Child MSF-F SOS VdE Ouadda Coopi Coopi CRCA Ngaounday IMC Markounda Kabo ICRC OCHA MSF-F UNHCR Paoua Batangafo Kaga-Bandoro Koui Boguila UNICEF Bocaranga TGH Coopi Mbrès Bria WFP Bouca SCI CRS INVISIBLE FAO Bossangoa MSF-H CHILDREN UNDSS Bozoum COHEB Grimari Bakouma SCI UNFPA Sibut Bambari Bouar SFCG Yaloké Mboki ACTED Bossembélé ICRC MSF-F ACF Obo Cordaid Alindao Zémio CRCA SCI Rafaï MSF-F Bangassou Carnot ACTED Cordaid Bangui* ALIMA ACTED Berbérati Boda Mobaye Coopi CRS Coopi DRC Bimbo EMERGENCY Ouango COHEB Mercy Corps Mercy Corps CRS FCA Mbaïki ACF Cordaid SCI SCI IMC Batalimo CRS Mercy Corps TGH MSF-H Nola COHEB Mercy Corps SFCG MSF-CH IMC SFCG COOPI SCI MSF-B ICRC SCI MSF-H ICRC ICDI CRS SCI CRCA ACF COOPI ICRC UNHCR IMC AHA WFP UNHCR AHA CRF UNDSS MSF-CH OIM UNDSS COHEB OCHA WFP FAO ACTED DEMOCRATIC WHO PU-AMI UNHCR UNDSS WHO CRF MSF-H MSF-B UNFPA REPUBLIC UNICEF UNICEF 50km *More than 50 humanitarian organizations work in the CAR with an office in Bangui. -

China Versus Vietnam: an Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

A CNA Occasional Paper China versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Distribution unlimited. for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA FOREWORD This legal analysis was commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. policy options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, USN, Judge Advocate Corps (ret.),1 the author of this analysis, is to provide U.S. -

Shifting the Political Strategy of the UN Peacekeeping Mission in the Central African Republic

Shifting the Political Strategy of the UN Peacekeeping Mission in the Central African Republic Briefing Note by the Stimson Center | 12 October 2016 Violence against civilians in the Central African Republic (CAR) is complex, driven by numerous conflicts at different levels. A national-level peace agreement may contribute to stability, but cannot fully address these diverse conflict drivers. Efforts by the UN peacekeeping mission in CAR, MINUSCA, to support a political solution to the conflict have so far been undermined by armed groups’ competing economic interests; the CAR government’s lack of commitment; the persistence of diverse local conflicts; and the mission’s own weaknesses. In order to protect civilians from violence and promote stability, MINUSCA must shift its political strategy to navigate these challenges. Recommendations: MINUSCA should place greater focus on local-level conflict response and on intercommunal reconciliation at the local and national levels. Member states should provide financial and political support to complement and advance these initiatives, including at the Brussels donor conference in November. The relationship between MINUSCA and the CAR government is beginning to show signs of strain. Member states should monitor the situation and take diplomatic action if necessary to prevent a pattern of improper obstruction by the CAR government. MINUSCA should improve its early warning and early response capabilities, including by setting up Joint Operations Centers in its field offices. MINUSCA should step up its efforts to arrest suspected perpetrators of serious crimes to put pressure on armed groups and to bring them back to the negotiating table. MINUSCA’s military protection of civilians approach aims to enforce “weapons- free zones” to restrict armed group movements. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

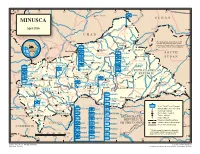

MINUSCA T a Ou M L B U a a O L H R a R S H Birao E a L April 2016 R B Al Fifi 'A 10 H R 10 ° a a ° B B C H a VAKAGA R I CHAD

14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° ZAMBIA Am Timan é Aoukal SUDAN MINUSCA t a ou m l B u a a O l h a r r S h Birao e a l April 2016 r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh Garba The boundaries and names shown ouk ahr A Ouanda and the designations used on this B Djallé map do not imply official endorsement Doba HQ Sector Center or acceptance by the United Nations. CENTRAL AFRICAN Sam Ouandja Ndélé K REPUBLIC Maïkouma PAKISTAN o t t SOUTH BAMINGUI HQ Sector East o BANGORAN 8 BANGLADESH Kaouadja 8° ° SUDAN Goré i MOROCCO u a g n i n i Kabo n BANGLADESH i V i u HAUTE-KOTTO b b g BENIN i Markounda i Bamingui n r r i Sector G Batangafo G PAKISTAN m Paoua a CAMBODIA HQ Sector West B EAST CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro Yangalia RWANDA CENTRAL AFRICAN BANGLADESH m a NANA Mbrès h OUAKA REPUBLIC OUHAM u GRÉBIZI HAUT- O ka Bria Yalinga Bossangoa o NIGER -PENDÉ a k MBOMOU Bouca u n Dékoa MAURITANIA i O h Bozoum C FPU CAMEROON 1 OUHAM Ippy i 6 BURUNDI Sector r Djéma 6 ° a ° Bambari b ra Bouar CENTER M Ouar Baoro Sector Sibut Baboua Grimari Bakouma NANA-MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO- BASSE MBOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KOTTO m Bossembélé GRIBINGUI M b angúi bo er ub FPU BURUNDI 1 mo e OMBELLA-MPOKOYaloke Zémio u O Rafaï Boali Kouango Carnot L Bangassou o FPU BURUNDI 2 MAMBÉRÉ b a y -KADEI CONGO e Bangui Boda FPU CAMEROON 2 Berberati Ouango JTB Joint Task Force Bangui LOBAYE i Gamboula FORCE HQ FPU CONGO Miltary Observer Position 4 Kade HQ EGYPT 4° ° Mbaïki Uele National Capital SANGHA Bondo Mongoumba JTB INDONESIA FPU MAURITANIA Préfecture Capital Yokadouma Tomori Nola Town, Village DEMOCRATICDEMOCRATIC Major Airport MBAÉRÉ UNPOL PAKISTAN PSU RWANDA REPUBLICREPUBLIC International Boundary Salo i Titule g Undetermined Boundary* CONGO n EGYPT PERU OFOF THE THE CONGO CONGO a FPU RWANDA 1 a Préfecture Boundary h b g CAMEROON U Buta n GABON SENEGAL a gala FPU RWANDA 2 S n o M * Final boundary between the Republic RWANDA SERBIA Bumba of the Sudan and the Republic of South 0 50 100 150 200 250 km FPU SENEGAL Sudan has not yet been determined.