The Accentual Structure of Estonian Syllabic- Accentual Iambic Tetrameter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HACETTEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ GÜZEL SANATLAR ENSTİTÜSÜ Yaylı Çalgılar Anasanat Dalı EDUARD TUBİN KONTRABAS KONÇERTOSU VE

HACETTEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ GÜZEL SANATLAR ENSTİTÜSÜ Yaylı Çalgılar Anasanat Dalı EDUARD TUBİN KONTRABAS KONÇERTOSU VE İCRASINDAKİ ZORLUK DERECELERİ’NİN ÖLÇÜMÜ Özlem ER CİVELEK Sanatta Yeterlilik Sanat Çalışması Raporu Ankara, 2021 HACETTEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ GÜZEL SANATLAR ENSTİTÜSÜ Yaylı Çalgılar Anasanat Dalı EDUARD TUBİN KONTRABAS KONÇERTOSU VE İCRASINDAKİ ZORLUK DERECELERİ’NİN ÖLÇÜMÜ Özlem ER CİVELEK Sanatta Yeterlilik Sanat Çalışması Raporu Ankara, 2021 EDUARD TUBİN KONTRABAS KONÇERTOSU VE İCRASINDAKİ ZORLUK DERECELERİ’NİN ÖLÇÜMÜ Danışman: Prof. Dr. Burak KARAAĞAÇ Yazar: Özlem ER CİVELEK ÖZ Estonyalı besteci Eduard Tubin’in 1948 yılında yazdığı kontrabas konçertosu, kontrabas repertuvarına büyük ölçüde katkı sağlamıştır. Günümüzde kontrabas çalan müzisyenlerin repertuvarlarında yer alan ve beğenilen bu eserin, diğer kontrabas eserleri arasında; melodik yapı, teknik ve ritmik zorluk bakımından seslendirilmeye değer olduğu söylenebilir. Bu araştırmanın amacı; meydana gelen zorlukların tespitini yapmak ve bulguların yorumuyla, bazı çözüm önerilerini ortaya koymaktır. Çalışmada konçertonun icrası esnasında karşılaşılabilecek melodik, teknik ve ritmik zorlukların tespit edilmesi için alanında uzman kişilere danışılarak anket formu oluşturulmuştur. Hazırlanan anket formu, Türkiye’deki Üniversitelerin Devlet Konservatuvarlarındaki akademisyenlere ve senfoni orkestralarında yer alan kontrabas sanatçılarına dağıtılmıştır. Araştırma nitel araştırma yöntemidir. Veriler amaçlı örnekleme yöntemi ile incelenmiştir. Araştırma; akademisyen ve kontrabas sanatçılarının -

Konrad Mägi 9

SISUKORD CONTENT 7 EESSÕNA 39 KONRAD MÄGI 9 9 FOREWORD 89 ADO VABBE 103 NIKOLAI TRIIK 13 TRADITSIOONI 117 ANTS LAIKMAA SÜNNIKOHT 136 PAUL BURMAN 25 THE BIRTHPLACE OF 144 HERBERT LUKK A TRADITION 151 ALEKSANDER VARDI 158 VILLEM ORMISSON 165 ENDEL KÕKS 178 JOHANNES VÕERAHANSU 182 KARL PÄRSIMÄGI 189 KAAREL LIIMAND 193 LEPO MIKKO 206 EERIK HAAMER 219 RICHARD UUTMAA 233 AMANDUS ADAMSON 237 ANTON STARKOPF Head tartlased, Lõuna-Eesti väljas on 16 tema tööd eri loominguperioodidest. 11 rahvas ja kõik Eesti kunstisõbrad! Kokku on näitusel eksponeeritud 57 maali ja 3 skulptuuri 17 kunstnikult. Mul on olnud ammusest ajast soov ja unistus teha oma kunstikollektsiooni näitus Tartu Tänan väga meeldiva koostöö eest Tartu linnapead Kunstimuuseumis. On ju eesti maalikunsti sünd 20. Urmas Klaasi ja Tartu linnavalitsust, Signe Kivi, sajandi alguses olnud olulisel määral seotud Tartuga Hanna-Liis Konti, Jaanika Kuznetsovat ja Tartu ja minu kunstikogu tuumiku moodustavadki sellest Kunstimuuseumi kollektiivi. Samuti kuulub tänu perioodist ehk eesti kunsti kuldajast pärinevad tööd. meie meeskonnale: näituse kuraatorile Eero Epnerile, kujundajale Tõnis Saadojale, graafilisele Tartuga on seotud mitmed meie kunsti suurkujud, disainerile Tiit Jürnale, meediaspetsialistile Marika eesotsas Konrad Mägiga. See näitus on Reinolile ja Inspiredi meeskonnale, keeletoimetajale pühendatud Eesti Vabariigi 100. juubelile ning Ester Kangurile, tõlkijale Peeter Tammistole ning Konrad Mägi 140. sünniaastapäeva tähistamisele. koordinaatorile Maris Kunilale. Suurim tänu kõigile, kes näituse õnnestumisele kaasa on aidanud! Näituse kuraator Eero Epner on samuti Tartus sündinud ja kasvanud ning lõpetanud Meeldivaid kunstielamusi soovides kunstiajaloolasena Tartu Ülikooli. Tema Enn Kunila nägemuseks on selle näitusega rõhutada Tartu tähtsust eesti kunsti sünniloos. Sellest mõttest tekkiski näituse pealkiri: „Traditsiooni sünd“. -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP -

Time Models for Interlitteraria.Rtf

Interlitteraria , No. 4. World Poetry in the Postmodern Age . Tartu: University of Tartu Press, pp. 264–280 SOME TIME MODELS IN ESTONIAN TRADITIONAL, MODERN AND POSTMODERN POETRY Arne Merilai 1. Poems and time What is a poem? Any poem, be it either lyrical like the sonnets or epical like the ballads, is always a narrative of some kind. It tells us about an occurred event, internal or external, dramatical or whatever. It claims that things in some situation were so-and-so, that they had certain preconditions and corresponding consequences. Whatever the story is about, its defining metaphysical theme is always time. I would like to emphasize that I consider the appearance of time as the metaphysical base of the narration, i.e. in a very general sense of the word, and thus overlook the narratological problems of depicting it. The plot of the story can contain pro- or analepsises (looking forward or backward), it can be elliptic or resuming (accelerative), scenic or descriptive in style (one-to-one or retarding). The presentation of the story can be singulative, repetative or iterative (single, repeating or concentrating presentation of an event). What I bear in mind is that a poem, whatever its narratological structure, always expresses time by presenting an event with its prologue and epilogue. But what kind of time? It may present the mythological circular or cyclic time as it probably was by our ancient folklore. It may present the feeling of unbounded eternity, which is characteristic of religions – we should mention Christian mysticists Ernst Enno and Uku Masing here as Estonian modern symbolists. -

Helga Nõu Biograafia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Tartu University Library Helga Nõu biograafia Sündinud Tartus 22. septembril 1934 Tartu linna haigla sünnitusosakonnas. Perekonnanimi neiuna Raukas. Isa metsainspektor Aleksander Friedrich Raukas (25.3.1900 Vaimastveres - 11.1.1988 Saltsjöbadenis). Ema käsitööõpetaja Elsa Raukas (21.2.1906 Tartus - 25.5.1981 Saltsjöbadenis), sündinud Reiman. Vend Arvo (s. 7.7.1937) on insener. Vend Rein (s. 19.11.1939) on olnud majandusjuht ettevõtetes. Elanud Eestis Kohtlas 1934, Tallinnas 1934-1941 (Pelgulinnas Oskari (hiljem Ristiku) 22-2, 1934- 1938, Raua 34-6 (hiljem 8-6) 1938-1941) ja Pärnus 1941-1944 (Jalaka 4). Põgeneud Rootsi koos vanemate ja vendadega septembris 1944. Rootsis põgenikelaagrites Visbys, Blackstadis, Källvikis, Ribbingelundis, Lovöl, Vikingshillis, Tynningöl ja Väddöbackas 1944-1945. Pärast Adelsöl 1945-1950 (Hallstas), Stuvstas-Huddinges 1950-1957 (Sofiebergsvägen 14) ja Uppsalas alates 1957 (Luthagsesplanaden 36 A 1957-1959, Gröna gatan 25 C 1959-1969 ja Sunnerstas Askvägen 18 A alates 1969). Elab ka pooleldi Tallinnas (Raua 8-6) alates 2000.a. Õppinud Pärnu Linna V algkoolis 1942-1944, Adelsö algkoolis 1945-1948, kodus Adelsöl Hermodsi Korrespondentsinstituudi reaalkursust 1949-1950 ja Stockholmis Södermalmi Högre Allmänna Läroverket för flickor 1950-1955, mille lõpetas abituriendina. Õppinud seminaris Folkskoleseminariet för kvinnliga elever Stockholmis 1955-1957 ja lõpetanud selle keskastme algkooliõpetaja kutsega. Ekstra algkooliõpetaja Stockholmi koolidistriktis Örby koolis 1957-1958. Ekstra algkooliõpetaja Balingsta koolis Södra Hagundas 1958-1961. Ekstra ordinaarie algkooliõpetaja alates 1959. Vikarieeriv alg- ja keskastme algkooliõpetaja Uppsalas Sunnersta koolis perioodide kaupa 1973- 1976. Vikarieeriv alg- ja keskastme algkooliõpetaja Uppsalas Eriksbergi- Hågadali koolis perioodide kaupa 1976. -

Table of Contents.Pdf

Contents Foreword and Acknowledgments ................................................................... xvii Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 The Oral Tradition ................................................................................................ 15 When I Escape the Manor ............................................................................. 17 A Dull Life Is a Sorry Thing ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 Brother’s War Song (extract) .......................................................................... 18 Reiner Brocmann ................................................................................................... 19 How Blessed Is the Man ............................................................................... 21 Käsu Hans .............................................................................................................. 23 Ah Me! Poor Tartu Town! ............................................................................. 24 Kulli Jüri ................................................................................................................. 29 Song 64. What Did Jesu’s Little Tom Tit Do? ............................................... 31 Song 81. God Invites All the People ............................................................. 31 Song 83. Towns and Lands Will Grow and Stand .................................... 32 Joachim Gottlieb Schwabe -

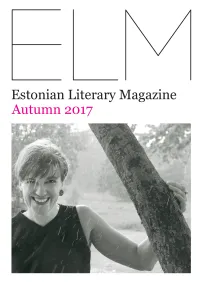

Estonian Literary Magazine · Autumn 2017 · Photo by Kalju Suur Kalju by Maimu Berg · Photo

Contents 2 A women’s self-esteem booster by Aita Kivi 6 Tallinn University’s new “Estonian Studies” master´s program by Piret Viires 8 The pain treshold. An interview with the author Maarja Kangro by Tiina Kirss 14 The Glass Child by Maarja Kangro 18 “Here I am now!” An interview with Vladislav Koržets by Jürgen Rooste 26 The signs of something going right. An interview with Adam Cullen 30 Siuru in the winds of freedom by Elle-Mari Talivee 34 Fear and loathing in little villages by Mari Klein 38 Being led by literature. An interview with Job Lisman 41 2016 Estonian Literary Awards by Piret Viires 44 Book reviews by Peeter Helme and Jürgen Rooste A women’s self-esteem booster by Aita Kivi The Estonian writer and politician Maimu Berg (71) mesmerizes readers with her audacity in directly addressing some topics that are even seen as taboo. As soon as Maimu entered the Estonian (Ma armastasin venelast, 1994), which literary scene at the age of 42 with her dual has been translated into five languages. novel Writers. Standing Lone on the Hill Complex human relationships and the (Kirjutajad. Seisab üksi mäe peal, 1987), topic of homeland are central in her mod- her writing felt exceptionally refreshing and ernist novel Away (Ära, 1999). She has somehow foreign. Reading the short stories also psychoanalytically portrayed women’s and literary fairy tales in her prose collection fears and desires in her prose collections I, Bygones (On läinud, 1991), it was clear – this Fashion Journalist (Mina, moeajakirjanik, author can capably flirt with open-minded- 1996) and Forgotten People (Unustatud ness! It was rare among Estonian authors at inimesed, 2007). -

NARVA COLLEGE of the UNIVERSITY of TARTU DIVISION of FOREIGN LANGUAGES

NARVA COLLEGE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TARTU DIVISION of FOREIGN LANGUAGES Kristina Shapiro ESTONIAN POETRY IN ENGLISH: MEANING IN TRANSLATION Bachelor’s thesis Supervisor: Lect. N.Raud, PhD NARVA 2015 PREFACE The place of Estonian poetry in world poetry has always been dependent on the fact that the Estonian language is spoken and understood by a comparatively small number of people. Due to particularities in grammar and vocabulary, Estonian stands rather isolated from other languages. One should invest in proper learning of Estonian to understand it. Moreover, the amount of Estonian speakers around the world makes it hard for Estonian poetry to be introduced to general public. That is why translation of Estonian poetry into English is needed. The present Bachelor’s thesis, titled “Estonian Poetry in English: Meaning in Translation”, is aimed to reveal the difficulties that might occur while translating Estonian poetry into English. The paper consists of four parts. The introduction introduces such notions as poetry, Estonian poetry, Estonian poetry in English. Chapter I “Aspects of Poetry Translation“ overviews theories of poetry translation aspects as well as techniques and poetry genre features and problems. Chapter II “Estonian Poetry in English Translations: Poetic Meaning“ focuses on the problems of translation from Estonian into English by analysing opinions and experiences of translators, their points of view on difficulties which might occur when translating poetry, the Estonian one in particular. It includes the analysis of poems written by the most famous Estonian writers of the 20th century – Marie Under and Doris Kareva. The conclusion sums up the results of the research and comments on the hypothesis. -

Sauel Tähistati Eesti Vabariigi 90. Sünnipäeva Mitmete Üritustega

Sauel tähistati Eesti Vabariigi 90. sünnipäeva mitmete üritustega Loe lk. 2 - 7 INFOLEHT NR. 6 (276) 1. märts 2008 Tasuta SAUE – 14. MÄRTS ON KODUNE LINN EMAKEELEPÄEV LINNAVOLIKOGUS LINNAVALITSUSES lk. 11 7. VEEBRUARIL TOIMUS SAUE GÜMNAASIUMIS AJALOO- KONVERENTS lk. 8 HUVI- KESKUS PÄEVA- KESKUS lk. 12 - 13 SAUELANE LIIKUMA lk. 14 2 / SAUE SÕNA –276 / EESTI VABARIIGI 90. SÜNNIPÄEV 1. märts 2008 Sauel tähistati Eesti Vabariigi 90. sünnipäeva mitmete üritustega. Linnavolikogu ja Linnavalitsuse poolt 24. veebruaril kell 13.00 volikogu esimees Valdis Toomast, Euroopa rivistus Saue Kristliku aseesimees Urmas Viilmaa ja abilinnapea Parlamendis Rafael Amos, kes pidas päevakohase kõne. Vabakiriku pargis tähistati asuva Mälestuskivi Eesti Vabariigi juurde Kaitseliidu 90. aastapäeva Harju Maleva Saue Selle nädala teisipäeval ja kolmapäeval Kompanii auvahtkond. tähistati Brüsselis Euroopa Parlamendis Eesti Vabariigi 90. aastapäeva. Aastapäevaüritused korraldasid koostöös Riigikoguga Eestist valitud Euroopa Parlamendi liikmed Tunne Kelam, Marianne Mikko, Siiri Oviir, Katrin Saks, Toomas Savi ja Andres Tarand. Teisipäeval Kangelaslikkusest mõtiskles Saue avati Eesti Instituudi koostatud fotonäitus kompanii pealik, nooremleitnant Jüri “Eesti Vabariik 90”. Lisaks Eesti ajalugu Pääsuke, küünlad süütasid juubelisõnade tutvustavale väljapanekule näidati Rao saatel Urmas Viilma ja Vabakiriku pastor Heidmetsa dokumentaal-animafilmi Vahur Utno. “Eesti elulood”. Näituse avamisest võtsid Järgnes jumalateenistus. osa Riigikogu esimees Ene Ergma ja 22. veebruaril -

Thesis with Signature Marii Valjataga

A small nation in monuments A study of ruptures in Estonian memoryscape and discourse in the 20th century Marii Väljataga Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, June 30, 2016 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization A small nation in monuments A study of ruptures in Estonian memoryscape and discourse in the 20th century Marii Väljataga Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Professor Pavel Kolář (EUI) - Supervisor Professor Alexander Etkind (EUI) Professor Siobhan Kattago (University of Tartu) Prof. dr hab. Jörg Hackmann (University of Szczecin, University of Greifswald) © Marii Väljataga, 2016 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I, Marii Väljataga, certify that I am the author of the work A small nation in monuments. A study of ruptures in Estonian memoryscape and discourse in the 20th century I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297). -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0073 Notes

8) credits block, add ater Publishers: >> and Fennica Gehrman (www.fennicagehrmann.i); Music Finland Oy; printed by permission of Fennica Gehrman Oy, Helsinki, 2007; www.fennicagehrmann.i); ): YL (c/o www.sulasol.i); P ): YL (c/o www.sulasol.i); can VELJO TORMIS: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION by Folke Bohlin The Estonian composer Veljo Tormis (born in 1930) has gradually become internationally recognised as one of the most outstanding composers of choral music in our time. Before Estonia became a free state again in 1991 Tormis was ranked among the leading composers of the Soviet Union – but as a nonconformist who often ran into trouble with the Soviet authorities because of the texts he used in his songs. The fact that Tormis has written for all sorts of choral ensembles has its background in the highly developed standard of Estonian choruses. Many of his songs for male- voice choir were written for Gustav Ernesaks’ famous State Academic Choir, through which they became widely spread on concert tours throughout the Soviet Union. But these days Tormis is sung also in the west, which has inspired choirs in a number of countries to commission works from him. In the selection on this CD there are a few settings of texts by twentieth-century Estonian poets but all the others use folk texts from different periods. Tormis has always been fascinated by folksongs. They have inspired him not only his highly characteristic choral arrangements but also his very special way of building his own music on folk-music elements. Tormis has repeatedly used texts from the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, a collection of folk-texts from pre-Christian and medieval times which are closely related to old Estonian songs. -

The History of Exile Estonian Literature and Literary Archives Rutt Hinrikus Estonian Literary Museum

The History of Exile Estonian Literature and Literary Archives Rutt Hinrikus Estonian Literary Museum In January 2009, a rather voluminous piece of literary history spanning 800 pages was presented in Tallinn – “Estonian Literature in Exile in the 20th Century”.1 The first 250 pages of this book provide an overview of the prose, followed by overviews of memoirs, drama, poetry, children’s literature and literature in translation. At the end there are overviews of reprints, literary criticism and literary studies. Parts of the book are reprints – all chapters except the most voluminous one on prose have previously been published as fascicles since 1993.2 The publication of this book denotes the reception of Estonian émigré literature on metalevel and provides the reader with interpretations and explanations. The length of the journey which separated émigré literature from disavowal and led to a joint restoration of Estonian literature is illustrated by two recollections. It was 1982 when the head of the Estonian Society for the Development of Friendly Ties Abroad (Välismaaga Sõprussidemete Arendamise Eesti Ühing) asked me if literature which was written in Estonian in Sweden or elsewhere, is Estonian literature. I stuttered my response – in this culturally clean “lawful space” of Soviet state security I felt a bit like a mouse being tossed around by a cat – that at least the work of authors whose creative work began in Estonia was Estonian literature. I wasn’t being questioned, I was being tested. I asked myself where the literature belonged, which was written by authors whose creative work began abroad. I had always thought of it as Estonian émigré literature, meaning, not as pieces of literary creation but more as forbidden fruit resembling the golden apples which grew on strange trees in 1 Kruuspere, Piret (toim) Eesti kirjandus paguluses XX sajandil.