Ravenspiral Guide an Informal Guide to Music Theory As It Relates to Composition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

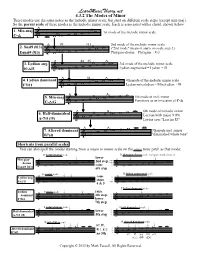

View Printable PDF of 4.2 the Modes of Minor

LearnMusicTheory.net 4.3.2 The Modes of Minor These modes use the same notes as the melodic minor scale, but start on different scale steps (except min-maj). So the parent scale of these modes is the melodic minor scale. Each is associated with a chord, shown below. 1. Min-maj 1st mode of the melodic minor scale C- w wmw ^ & w wmbw w w b9 §13 2nd mode of the melodic minor scale 2. Susb9 (§13) wmw w ("2nd mode" means it starts on scale step 2.) Dsusb9 (§13) & wmbw w w w Phrygian-dorian = Phyrgian + §13 #4 #5 3. Lydian aug. mbw 3rd mode of the melodic minor scale wmw w Lydian augmented = Lydian + #5 Eb ^ #5 & bw w w w #4 4. Lydian dominant 4th mode of the melodic minor scale w wmbw w F7#11 & w w w wm Lydian-mixolydian = Mixolydian + #4 5. Min-maj w w 5th mode of mel. minor wmw wmbw Functions as an inversion of C- C- ^ /G & w w ^ 6th mode of melodic minor 6. Half-diminished w w m w wmbw w Locrian with major 9 (§9) A-7b5 (§9) & w w Levine says "Locrian #2" w 7. Altered dominant wmbw w w w 7th mode mel. minor B7alt & wm w "diminished whole tone" Shortcuts from parallel scales You can also spell the modes starting from a major or minor scale on the same tonic pitch as that mode: D natural minor scale D phrygian-dorian scale (compare marked notes) lower Phrygian- I I 2nd step, I I dorian w bw w w raise _ w nw w w Dsusb9 (§13) & w w w _ & bw w w w 6th step _ w Eb major scale Eb lydian augmented scale Lydian aug. -

I. the Term Стр. 1 Из 93 Mode 01.10.2013 Mk:@Msitstore:D

Mode Стр. 1 из 93 Mode (from Lat. modus: ‘measure’, ‘standard’; ‘manner’, ‘way’). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; and, most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term ‘mode’ has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and since the 20th century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain phenomena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see Sound, §5(ii). For a discussion of mode in relation to ancient Greek theory see Greece, §I, 6 I. The term II. Medieval modal theory III. Modal theories and polyphonic music IV. Modal scales and traditional music V. Middle East and Asia HAROLD S. POWERS/FRANS WIERING (I–III), JAMES PORTER (IV, 1), HAROLD S. POWERS/JAMES COWDERY (IV, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 1), RUTH DAVIS (V, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 3), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(i)), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (a)–(d)), MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (e)–(i)), ALLAN MARETT, STEPHEN JONES (V, 5(i)), ALLEN MARETT (V, 5(ii), (iii)), HAROLD S. POWERS/ALLAN MARETT (V, 5(iv)) Mode I. -

Studies in Instrumentation and Orchestration and in the Recontextualisation of Diatonic Pitch Materials (Portfolio of Compositions)

Studies in Instrumentation and Orchestration and in the Recontextualisation of Diatonic Pitch Materials (Portfolio of Compositions) by Chris Paul Harman Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract: The present document examines eight musical works for various instruments and ensembles, composed between 2007 and 2011. Brief summaries of each work’s program are followed by discussions of instrumentation and orchestration, and analysis of pitch organization. Discussions of instrumentation and orchestration explore the composer’s approach to diversification of instrumental ensembles by the inclusion of non-orchestral instruments, and redefinition of traditional hierarchies among instruments in a standard ensemble or orchestral setting. Analyses of pitch organization detail various ways in which the composer renders diatonic -

Chromatic Sequences

CHAPTER 30 Melodic and Harmonic Symmetry Combine: Chromatic Sequences Distinctions Between Diatonic and Chromatic Sequences Sequences are paradoxical musical processes. At the surface level they provide rapid harmonic rhythm, yet at a deeper level they function to suspend tonal motion and prolong an underlying harmony. Tonal sequences move up and down the diatonic scale using scale degrees as stepping-stones. In this chapter, we will explore the consequences of transferring the sequential motions you learned in Chapter 17 from the asymmetry of the diatonic scale to the symmetrical tonal patterns of the nineteenth century. You will likely notice many similarities of behavior between these new chromatic sequences and the old diatonic ones, but there are differences as well. For instance, the stepping-stones for chromatic sequences are no longer the major and minor scales. Furthermore, the chord qualities of each individual harmony inside a chromatic sequence tend to exhibit more homogeneity. Whereas in the past you may have expected major, minor, and diminished chords to alternate inside a diatonic sequence, in the chromatic realm it is not uncommon for all the chords in a sequence to manifest the same quality. EXAMPLE 30.1 Comparison of Diatonic and Chromatic Forms of the D3 ("Pachelbel") Sequence A. 624 CHAPTER 30 MELODIC AND HARMONIC SYMMETRY COMBINE 625 B. Consider Example 30.1A, which contains the D3 ( -4/ +2)-or "descending 5-6"-sequence. The sequence is strongly goal directed (progressing to ii) and diatonic (its harmonies are diatonic to G major). Chord qualities and distances are not consistent, since they conform to the asymmetry of G major. -

Mode Handout Without Examples

The 24 Essential Mode/Chord Structures Modes & Symbols of the Major Scale MAJOR SCALE MODE FORMULA I: MAJOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL I: 1-1(1) – IONIAN ma13 EXAMPLES: In the Key of C: C-C(C) With C as the Root: C-C(C) MAJOR SCALE FORMULA II: MAJOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL II: 2-2(1) – DORIAN mi13 EXAMPLES: In the Key of C: D-D(C) With C as the Root: C-C(Bb) MAJOR SCALE FORMULA III: MAJOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL III: 3-3(1) – PHRYGIAN mi11(b9,b13) EXAMPLES: In the Key of C: E-E(C) With C as the Root: C-C(Ab) MAJOR SCALE FORMULA IV: MAJOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL IV: 4-4(1) – LYDIAN ma13(#11) EXAMPLES: In the Key of C: F-F(C) With C as the Root: C-C(G) MAJOR SCALE FORMULA V: MAJOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL V: 5-5(1) – MIXOLYDIAN 13 EXAMPLES: In the Key of C: G-G(C) With C as the Root: C-C(F) MAJOR SCALE FORMULA VI: MAJOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL VI: 6-6(1) – AEOLIAN mi11(b13) EXAMPLES: In the Key of C: A-A(C) With C as the Root: C-C(Eb) MAJOR SCALE FORMULA VII: MAJOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL VII: 7-7(1) – LOCRIAN mi11(b5,b9,b13) EXAMPLES: In the Key of C: B-B(C) With C as the Root: C-C(Db) Modes & Symbols of the Melodic Minor Scale MELODIC MINOR FORMULA I: MELODIC MINOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL I: 1-1(1mm) – MELODIC MINOR mi(ma13) EXAMPLES: In the Key of Cmm: C-C(Cmm) With C as the Root: C-C(Cmm) MELODIC MINOR FORMULA II: MELODIC MINOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL II: 2-2(1mm) – DORIAN b2 Mi13(b9) EXAMPLES: In the Key of Cmm: D-D(Cmm) With C as the Root: C-C(Bbmm) MELODIC MINOR FORMULA III: MELODIC MINOR SCALE MODE SYMBOL III: 3-3(1mm) – LYDIAN AUGMENTED +ma13(#11) EXAMPLES: In the Key of Cmm: Eb-Eb(Cmm) -

Proquest Dissertations

A comparison of embellishments in performances of bebop with those in the music of Chopin Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Mitchell, David William, 1960- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 23:23:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/278257 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the miaofillm master. UMI films the text directly fi^om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fi-om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and contLDuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

How to Incorporate Bebop Into Your Improvisation by Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics

How to Incorporate Bebop into Your Improvisation By Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics • Bebop Characteristics & Style • Scales & Arpeggios • Exercises & Patterns • Articulations & Accents • Listening Bebop Characteristics & Style • Developed in the early to mid 1940’s • Medium to fast tempos • Rapid chord progressions / changes • Instrumental “virtuosity” • Simple to complex harmony - altered chords / substitutions • Dominant syncopation of rhythms • New melodies over existing chord changes - Contrafacts Scales & Arpeggios • Scales and arpeggios are the building blocks for harmony • Use of the half-step interval and rapid arpeggiation are characteristic of bebop playing • Because bebop is often played at a fast tempo with rapidly changing chords, it’s crucial to practice your scales and arpeggios in ALL KEYS! Scales & Arpeggios • Scales you should be familiar with: • Major Scale - Pentatonic: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 • Minor Scales - Pentatonic: 1, b3, 4, 5, b7; Natural Minor, Dorian Minor, Harmonic Minor, Melodic Minor • Dominant Scales - Mixolydian Mode, Bebop Scales, 5th Mode of Harmonic Minor (V7b9), Altered Dominant / Diminished Whole Tone (V7alt, b9#9b13), Dominant Diminished / Diminished starting with a half step (V7b9#9 with #11, 13) • Half-diminished scale - min7b5 (7th mode of major scale) • Diminished Scale - Starting with a whole step (WHWHWHWH) Scales & Arpeggios • Chords and Arpeggios to work in all keys: • Major triad, Maj6/9, Maj7, Maj9, Maj9#11 • Minor triad, m6/9, m7, m9, m11, minMaj7 • Dominant 7ths • Natural extensions - 9th, 13th -

Stravinsky and the Octatonic: a Reconsideration

Stravinsky and the Octatonic: A Reconsideration Dmitri Tymoczko Recent and not-so-recent studies by Richard Taruskin, Pieter lary, nor that he made explicit, conscious use of the scale in many van den Toorn, and Arthur Berger have called attention to the im- of his compositions. I will, however, argue that the octatonic scale portance of the octatonic scale in Stravinsky’s music.1 What began is less central to Stravinsky’s work than it has been made out to as a trickle has become a torrent, as claims made for the scale be. In particular, I will suggest that many instances of purported have grown more and more sweeping: Berger’s initial 1963 article octatonicism actually result from two other compositional tech- described a few salient octatonic passages in Stravinsky’s music; niques: modal use of non-diatonic minor scales, and superimposi- van den Toorn’s massive 1983 tome attempted to account for a tion of elements belonging to different scales. In Part I, I show vast swath of the composer’s work in terms of the octatonic and that the rst of these techniques links Stravinsky directly to the diatonic scales; while Taruskin’s even more massive two-volume language of French Impressionism: the young Stravinsky, like 1996 opus echoed van den Toorn’s conclusions amid an astonish- Debussy and Ravel, made frequent use of a variety of collections, ing wealth of musicological detail. These efforts aim at nothing including whole-tone, octatonic, and the melodic and harmonic less than a total reevaluation of our image of Stravinsky: the com- minor scales. -

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: a Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: A Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1 Dmitri Tymoczko The diatonic scale, considered as a subset of the twelve chromatic pitch classes, possesses some remarkable mathematical properties. It is, for example, a "deep scale," containing each of the six diatonic intervals a unique number of times; it represents a "maximally even" division of the octave into seven nearly-equal parts; it is capable of participating in a "maximally smooth" cycle of transpositions that differ only by the shift of a single pitch by a single semitone; and it has "Myhill's property," in the sense that every distinct two-note diatonic interval (e.g., a third) comes in exactly two distinct chromatic varieties (e.g., major and minor). Many theorists have used these properties to describe and even explain the role of the diatonic scale in traditional tonal music.2 Tonal music, however, is not exclusively diatonic, and the two nondiatonic minor scales possess none of the properties mentioned above. Thus, to the extent that we emphasize the mathematical uniqueness of the diatonic scale, we must downplay the musical significance of the other scales, for example by treating the melodic and harmonic minor scales merely as modifications of the natural minor. The difficulty is compounded when we consider the music of the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in which composers expanded their musical vocabularies to include new scales (for instance, the whole-tone and the octatonic) which again shared few of the diatonic scale's interesting characteristics. This suggests that many of the features *I would like to thank David Lewin, John Thow, and Robert Wason for their assistance in preparing this article. -

Towards a Generative Framework for Understanding Musical Modes

Table of Contents Introduction & Key Terms................................................................................1 Chapter I. Heptatonic Modes.............................................................................3 Section 1.1: The Church Mode Set..............................................................3 Section 1.2: The Melodic Minor Mode Set...................................................10 Section 1.3: The Neapolitan Mode Set........................................................16 Section 1.4: The Harmonic Major and Minor Mode Sets...................................21 Section 1.5: The Harmonic Lydian, Harmonic Phrygian, and Double Harmonic Mode Sets..................................................................26 Chapter II. Pentatonic Modes..........................................................................29 Section 2.1: The Pentatonic Church Mode Set...............................................29 Section 2.2: The Pentatonic Melodic Minor Mode Set......................................34 Chapter III. Rhythmic Modes..........................................................................40 Section 3.1: Rhythmic Modes in a Twelve-Beat Cycle.....................................40 Section 3.2: Rhythmic Modes in a Sixteen-Beat Cycle.....................................41 Applications of the Generative Modal Framework..................................................45 Bibliography.............................................................................................46 O1 O Introduction Western -

Tonal Hierarchies in the Music of North India Mary A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref ri Journal of Experimental Psychology: General . „ u , C?Py 8ht 1984 by the 1984, Vol. 113, No. 3, 394-412 American Psychological Association, Inc. Tonal Hierarchies in the Music of North India Mary A. Castellano J. J. Bharucha Cornell University Dartmouth College Carol L. Krumhansl Cornell University SUMMARY Cross-culturally, most music is tonal in the sense that one particular tone, called the tonic, provides a focus around which the other tones are organized. The specific orga- nizational structures around the tonic show considerable diversity. Previous studies of the perceptual response to Western tonal music have shown that listeners familiar with this musical tradition have internalized a great deal about its underlying organization. Krumhansl and Shepard (1979) developed a probe tone method for quantifying the perceived hierarchy of stability of tones. When applied to Western tonal contexts, the measured hierarchies were found to be consistent with music-theoretic accounts. In the present study, the probe tone method was used to quantify the perceived hierarchy of tones of North Indian music. Indian music is tonal and has many features in common with Western music. One of the most significant differences is that the primary means of expressing tonality in Indian music is through melody, whereas in Western music it is through harmony (the use of chords). Indian music is based on a standard set of melodic forms (called rags), which are themselves built on a large set of scales (thats). The tones within a rag are thought to be organized in a hierarchy of importance. -

Chord-Scale Networks in the Music and Improvisations of Wayne Shorter

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 7 April 2018 Chord-Scale Networks in the Music and Improvisations of Wayne Shorter Garrett Michaelsen University of Massachusetts, Lowell, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Recommended Citation Michaelsen, Garrett (2018) "Chord-Scale Networks in the Music and Improvisations of Wayne Shorter," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol8/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. CHORD-SCALE NETWORKS IN THE MUSIC AND IMPROVISATIONS OF WAYNE SHORTER GARRETT MICHAELSEN ayne Shorter’s tune “E.S.P.,” first recorded on Miles Davis’s 1965 album of the same Wname , presents a number of fascinating challenges to harmonic analysis. Example 1 gives the tune’s lead sheet, which shows its melody and chord changes. In the first eight-bar phrase, the harmony moves at a slow, two-bar pace, sliding between chords with roots on E, F, and E beneath a repeating fourths-based melody that contracts to an A4–F4 major third in the last two bars. Shorter’s melody quite often emphasizes diatonic and chromatic ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths against the passing harmonies, thereby underscoring the importance of those extensions to the chords.