Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Printable PDF of 4.2 the Modes of Minor

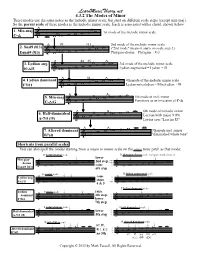

LearnMusicTheory.net 4.3.2 The Modes of Minor These modes use the same notes as the melodic minor scale, but start on different scale steps (except min-maj). So the parent scale of these modes is the melodic minor scale. Each is associated with a chord, shown below. 1. Min-maj 1st mode of the melodic minor scale C- w wmw ^ & w wmbw w w b9 §13 2nd mode of the melodic minor scale 2. Susb9 (§13) wmw w ("2nd mode" means it starts on scale step 2.) Dsusb9 (§13) & wmbw w w w Phrygian-dorian = Phyrgian + §13 #4 #5 3. Lydian aug. mbw 3rd mode of the melodic minor scale wmw w Lydian augmented = Lydian + #5 Eb ^ #5 & bw w w w #4 4. Lydian dominant 4th mode of the melodic minor scale w wmbw w F7#11 & w w w wm Lydian-mixolydian = Mixolydian + #4 5. Min-maj w w 5th mode of mel. minor wmw wmbw Functions as an inversion of C- C- ^ /G & w w ^ 6th mode of melodic minor 6. Half-diminished w w m w wmbw w Locrian with major 9 (§9) A-7b5 (§9) & w w Levine says "Locrian #2" w 7. Altered dominant wmbw w w w 7th mode mel. minor B7alt & wm w "diminished whole tone" Shortcuts from parallel scales You can also spell the modes starting from a major or minor scale on the same tonic pitch as that mode: D natural minor scale D phrygian-dorian scale (compare marked notes) lower Phrygian- I I 2nd step, I I dorian w bw w w raise _ w nw w w Dsusb9 (§13) & w w w _ & bw w w w 6th step _ w Eb major scale Eb lydian augmented scale Lydian aug. -

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

The Connection Between Jazz and Drug Abuse: a Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’S, 50’S, and 60’S

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship Musicology and Ethnomusicology 11-2019 The Connection Between Jazz and Drug Abuse: A Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s Aaron Olson University of Denver, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Olson, Aaron, "The Connection Between Jazz and Drug Abuse: A Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s" (2019). Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship. 52. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/52 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Musicology and Ethnomusicology at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. The Connection Between Jazz and Drug Abuse: A Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s This bibliography is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/52 The Connection between Jazz and Drug Abuse: A Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s. An Annotated Bibliography By: Aaron Olson November, 2019 From the 1940s to the 1960s drug abuse in the jazz community was almost at epidemic proportions. -

Victory and Sorrow: the Music & Life of Booker Little

ii VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSIC & LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE by DYLAN LAGAMMA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History & Research written under the direction of Henry Martin and approved by _________________________ _________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2017 i ©2017 Dylan LaGamma ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSICAL LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE BY DYLAN LAGAMMA Dissertation Director: Henry Martin Booker Little, a masterful trumpeter and composer, passed away in 1961 at the age of twenty-three. Little's untimely death, and still yet extensive recording career,1 presents yet another example of early passing among innovative and influential trumpeters. Like Clifford Brown before him, Theodore “Fats” Navarro before him, Little's death left a gap the in jazz world as both a sophisticated technician and an inspiring composer. However, unlike his predecessors Little is hardly – if ever – mentioned in jazz texts and classrooms. His influence is all but non-existent except to those who have researched his work. More than likely he is the victim of too early a death: Brown passed away at twenty-five and Navarro, twenty-six. Bob Cranshaw, who is present on Little's first recording,2 remarks, “Nobody got a chance to really experience [him]...very few remember him because nobody got a chance to really hear him or see him.”3 Given this, and his later work with more avant-garde and dissonant harmonic/melodic structure as a writing partner with Eric Dolphy, it is no wonder that his remembered career has followed more the path of James P. -

A Night in Tunisia (From Album “Legends Masterpieces)

ANALISI DELLE FORME COMPOSITIVE di alcuni notissimi brani jazz di Avv. Valentina Grande 1) Sonny Rollins - St.Thomas (Original) (from album “The Prestige Years”) 2) Dizzy Gillespie feat. Charlie Parker - A Night In Tunisia (from album “Legends Masterpieces) 3) Miles Davis – Godchild (from album “Birth of the cool”) 1) Sonny Rollins - St.Thomas (Original) 1956 (from album “Saxophone Colossus”/“The Prestige Years”) St. Thomas è un brano strumentale scritto dal tenorsassofonista jazz Sonny Rollins, nel periodo dell’hard bop, nell’anno 1956, anno in cui ai musicisti del periodo fu data la possibilità di estendere la durata delle registrazioni oltre i fatidici tre minuti concessi dai supporti 78 giri, grazie all’innovazione giunta con l’introduzione del long playing in vinile a 33 giri. Nel leggendario studio di Rudy Van Gelder, niente altro che il salotto della sua abitazione ad Hackensack, New Jersey, il 22 giugno di quell’anno il produttore Bob Weinstock, creatore dell’etichetta discografica Prestige, organizzò una seduta di registrazione per il sassofonista Sonny Rollins e il suo quartetto. Il frutto del lavoro di quella giornata confluì nell’album “Saxophone Colossus”, opera che nei decenni a venire avrebbe cambiato la vita di molti sassofonisti più o meno in erba. L’eccezionale quartetto convocato per l’occasione era completato da Tommy Flanagan al pianoforte, Doug Watkins al contrabbasso e Max Roach alla batteria. Tra i brani registrati in quell’occasione, il più noto è sicuramente St. Thomas, passato alla storia come uno dei primi “calypso” registrati nell’ambito del jazz. La forma del brano, di sedici misure, è una sorta di AABC in miniatura, con sezioni di quattro misure. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

BROWNIE the Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet

BROWNIE The Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet Dan Morgenstern Grammy Award for Best Album Notes 1990 Disc 1 1. DELILAH 8:04 Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: (V. Young) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 2. DARN THAT DREAM 4:02 Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (De Lange - V. Heusen) (ds) 3. PARISIAN THOROUGHFARE 7:16 (B. Powell) 4. JORDU 7:43 (D. Jordan) 5. SWEET CLIFFORD 6:40 (C. Brown) 6. SWEET CLIFFORD (CLIFFORD’S FANTASY)* 1:45 1~3: Los Angeles, August 2, 1954 (C. Brown) 7. I DON’T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANCE* 3:03 4~8: Los Angeles, August 3, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 8. I DON’ T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANC E 7:19 9~12: Los Angeles, August 5, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 9. STOMPIN’ AT TH E SAVOY 6:24 (Goodman - Sampson - Razaf - Webb) 10. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU 7:36 (C. Porter) 11. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU* 8:29 * Previously released alternate take (C. Porter) 12. I’ LL STRING ALONG WITH YOU 4:10 (Warren - Dubin) Disc 2 1. JOY SPRING* 6:44 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: 2. JOY SPRING 6:49 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 3. MILDAMA* 3:33 (M. Roach) Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (ds) 4. MILDAMA* 3:22 (M. Roach) Los Angeles, August 6, 1954 5. MILDAMA* 3:55 (M. Roach) 6. -

Sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 Songs, 14.2 Hours, 1.62 GB

Page 1 of 8 ...sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 songs, 14.2 hours, 1.62 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Go Now! 3:15 The Magnificent Moodies The Moody Blues 2 Waiting To Derail 3:55 Strangers Almanac Whiskeytown 3 Copperhead Road 4:34 Shut Up And Die Like An Aviator Steve Earle And The Dukes 4 Crazy To Love You 3:06 Old Ideas Leonard Cohen 5 Willow Bend-Julie 0:23 6 Donations 3 w/id Julie 0:24 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 7 Wheels Of Love 2:44 Anthology Emmylou Harris 8 California Sunset 2:57 Old Ways Neil Young 9 Soul of Man 4:30 Ready for Confetti Robert Earl Keen 10 Speaking In Tongues 4:34 Slant 6 Mind Greg Brown 11 Soap Making-Julie 0:23 12 Volunteer 1 w/ID- Tony 1:20 KSZN Broadcast Clips 13 Quittin' Time 3:55 State Of The Heart Mary Chapin Carpenter 14 Thank You 2:51 Bonnie Raitt Bonnie Raitt 15 Bootleg 3:02 Bayou Country (Limited Edition) Creedence Clearwater Revival 16 Man In Need 3:36 Shoot Out the Lights Richard & Linda Thompson 17 Semicolon Project-Frenaudo 0:44 18 Let Him Fly 3:08 Fly Dixie Chicks 19 A River for Him 5:07 Bluebird Emmylou Harris 20 Desperadoes Waiting For A Train 4:19 Other Voices, Too (A Trip Back To… Nanci Griffith 21 uw niles radio long w legal id 0:32 KSZN Broadcast Clips 22 Cold, Cold Heart 5:09 Timeless: Hank Williams Tribute Lucinda Williams 23 Why Do You Have to Torture Me? 2:37 Swingin' West Big Sandy & His Fly-Rite Boys 24 Madmax 3:32 Acoustic Swing David Grisman 25 Grand Canyon Trust-Terry 0:38 26 Volunteer 2 Julie 0:48 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 27 Happiness 3:55 So Long So Wrong Alison Krauss & Union Station -

AP Music Theory Course Description Audio Files ”

MusIc Theory Course Description e ffective Fall 2 0 1 2 AP Course Descriptions are updated regularly. Please visit AP Central® (apcentral.collegeboard.org) to determine whether a more recent Course Description PDF is available. The College Board The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of more than 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators, and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org. AP Equity and Access Policy The College Board strongly encourages educators to make equitable access a guiding principle for their AP programs by giving all willing and academically prepared students the opportunity to participate in AP. We encourage the elimination of barriers that restrict access to AP for students from ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups that have been traditionally underserved. Schools should make every effort to ensure their AP classes reflect the diversity of their student population. The College Board also believes that all students should have access to academically challenging course work before they enroll in AP classes, which can prepare them for AP success. -

“Dizzy” Gillespie Was One of the Most Important and Influential Jazz Trumpeters, After Louis Armstrong

35 lesson9 Meet the Great Jazz Legends dizzygillespie Photo: © Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress Vechten, Photo: © Carl Van IMPORTANT FACTS TO KNOW ABOUT JOHN “DIZZY” GILLESPIE Born: October 21, 1917, Cheraw, South Carolina Died: January 6, 1993, Englewood, New Jersey Period/Style of Jazz: Bebop, Afro-Cuban Jazz Instrument: Trumpet, bandleader and composer Major Compositions: A Night in Tunisia, Con Alma, Groovin’ High, Manteca Interesting Facts: Dizzy Gillespie invented the modern approach to jazz trumpet playing, which included extending the range of the instrument, improvising in a more linear fashion and playing with dramatic bursts with large interval leaps. He was among the first to use Afro-Cuban music in jazz. Included Listening: A Night in Tunisia Track 9 36 Meet the Great Jazz Legends ■ The Story of Dizzy Gillespie (1917–1993) ohn Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie was one of the most important and influential jazz trumpeters, after Louis Armstrong. Dizzy Gillespie, along with his colleagues Charlie Parker and Thelonious J Monk, are considered to be the “fathers” of the fast-and-furious style called bebop. Dizzy Gillespie was known for his soaring trumpet lines, his puffed cheeks and the tilted bell of his trumpet. He was loved by musicians and fans for his engaging personality and showmanship. Gillespie was inspired to play music by his father who was a bricklayer and part- time musician. Gillespie began playing the piano at the age of 4. He taught himself to play the trumpet by trial and error, with the help of a few friends at the age of 12. In 1935, Gillespie moved to Philadelphia with his mother, after the death of his father. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history.