14271Melodic Improvising Neu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Printable PDF of 4.2 the Modes of Minor

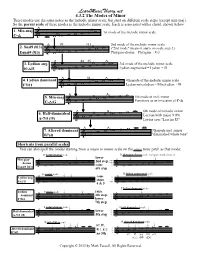

LearnMusicTheory.net 4.3.2 The Modes of Minor These modes use the same notes as the melodic minor scale, but start on different scale steps (except min-maj). So the parent scale of these modes is the melodic minor scale. Each is associated with a chord, shown below. 1. Min-maj 1st mode of the melodic minor scale C- w wmw ^ & w wmbw w w b9 §13 2nd mode of the melodic minor scale 2. Susb9 (§13) wmw w ("2nd mode" means it starts on scale step 2.) Dsusb9 (§13) & wmbw w w w Phrygian-dorian = Phyrgian + §13 #4 #5 3. Lydian aug. mbw 3rd mode of the melodic minor scale wmw w Lydian augmented = Lydian + #5 Eb ^ #5 & bw w w w #4 4. Lydian dominant 4th mode of the melodic minor scale w wmbw w F7#11 & w w w wm Lydian-mixolydian = Mixolydian + #4 5. Min-maj w w 5th mode of mel. minor wmw wmbw Functions as an inversion of C- C- ^ /G & w w ^ 6th mode of melodic minor 6. Half-diminished w w m w wmbw w Locrian with major 9 (§9) A-7b5 (§9) & w w Levine says "Locrian #2" w 7. Altered dominant wmbw w w w 7th mode mel. minor B7alt & wm w "diminished whole tone" Shortcuts from parallel scales You can also spell the modes starting from a major or minor scale on the same tonic pitch as that mode: D natural minor scale D phrygian-dorian scale (compare marked notes) lower Phrygian- I I 2nd step, I I dorian w bw w w raise _ w nw w w Dsusb9 (§13) & w w w _ & bw w w w 6th step _ w Eb major scale Eb lydian augmented scale Lydian aug. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White Home Address: 23271 Rosewood Oak Park, MI 48237 (917) 273-7498 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.walterwhite.com EDUCATION Banff Centre of Fine Arts Summer Jazz Institute – Advanced study of jazz performance, improvisation, composition, and 1985-1988 arranging. Performances with Dave Holland. Cecil Taylor, Muhal Richard Abrahms, David Liebman, (July/August) Richie Beirach, Kenny Wheeler, Pat LaBarbara, Julian Priester, Steve Coleman, Marvin Smith. The University of Miami 1983-1986 Studio Music and Jazz, Concert Jazz Band, Monk/Mingus Ensemble, Bebop Ensemble, ECM Ensemble, Trumpet. The Juilliard School 1981-1983 Classical Trumpet, Orchestral Performance, Juilliard Orchestra. Interlochen Arts Academy (High School Grades 10-12) 1978-1981 Trumpet, Band, Orchestra, Studio Orchestra, Brass Ensemble, Choir. Interlochen Arts Camp (formerly National Music Camp) 8-weeks Summers, Junior Orchestra (principal trumpet), Intermediate Band (1st Chair), Intermediate Orchestra (principal), 1975- 1979, H.S. Jazz Band (lead trumpet), World Youth Symphony Orchestra (section 78-79, principal ’81) 1981 Henry Ford Community College Summer Jazz Institute Summer Classes in improvisation, arranging, small group, and big band performance. 1980 Ferndale, Michigan, Public Schools (Grades K-9) 1968-1977 TEACHING ACCOMPLISHMENTS Rutgers University, Artist-in-residence Duties included coaching jazz combos, trumpet master 2009-2010 classes, arranging classes, big band rehearsals and sectionals, private lessons, and five performances with the Jazz Ensemble, including performances with Conrad Herwig, Wynton Marsalis, Jon Faddis, Terrell Stafford, Sean Jones, Tom ‘Bones’ Malone, Mike Williams, and Paquito D’Rivera Newark, NY, High School Jazz Program Three day residency with duties including general music clinics and demonstrations for primary and secondary students, coaching of Wind Ensemble, Choir, Jan 2011 Jazz Vocal Ensemble, and two performances with the High School Jazz Ensemble. -

2009 Tour Dates

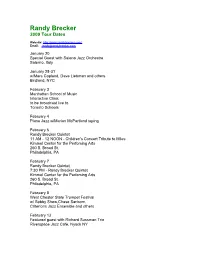

Randy Brecker 2009 Tour Dates Website: http://www.randybrecker.com/ Email: [email protected] January 20 Special Guest with Saleno Jazz Orchestra Salerno, Italy January 28-31 w/Marc Copland, Dave Liebman and others Birdland, NYC February 3 Manhattan School of Music Interactive Clinic to be broadcast live to Toronto Schools February 4 Piano Jazz w/Marian McPartland taping February 6 Randy Brecker Quintet 11 AM - 12 NOON - Children's Concert Tribute to Miles Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 7 Randy Brecker Quintet 7:30 PM - Randy Brecker Quintet Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 8 West Chester State Trumpet Festival w/ Bobby Shew,Chase Sanborn, Criterions Jazz Ensemble and others February 13 Featured guest with Richard Sussman Trio Riverspace Jazz Cafe, Nyack NY February 15 Special guest w/Dave Liebman Group Baltimore, Maryland February 20 - 21 Special guest w/James Moody Quartet Burmuda Jazz Festival March 1-2 Northeastern State Universitry Concert/Clinic Tahlequah, Oklahoma March 6-7 Concert/Clinic for Frank Foster and Break the Glass Foundation Sandler Perf. Arts Center Virginia Beach, VA March 17-25 Dates TBA European Tour w/Lynne Arriale quartet feat: Randy Brecker, Geo. Mraz A. Pinciotti March 27-28 Temple University Concert/Clinic Temple,Texas March 30 Scholarship Concert with James Moody BB King's NYC, NY April 1-2 SUNY Purchase Concert/Clinic with Jazz Ensemble directed by Todd Coolman April 4 Berks Jazz Festival w/Metro Special Edition: Chuck Loeb, Dave Weckl, Mitch Forman and others April 11 w/ Lynne Arriale Jazz Quartet Ft. -

Proquest Dissertations

A comparison of embellishments in performances of bebop with those in the music of Chopin Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Mitchell, David William, 1960- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 23:23:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/278257 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the miaofillm master. UMI films the text directly fi^om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fi-om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and contLDuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

David Liebman Papers and Sound Recordings BCA-041 Finding Aid Prepared by Amanda Axel

David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Finding aid prepared by Amanda Axel This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 30, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Berklee Archives Berklee College of Music 1140 Boylston St Boston, MA, 02215 617-747-8001 David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Scores and Charts................................................................................................................................... -

How to Incorporate Bebop Into Your Improvisation by Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics

How to Incorporate Bebop into Your Improvisation By Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics • Bebop Characteristics & Style • Scales & Arpeggios • Exercises & Patterns • Articulations & Accents • Listening Bebop Characteristics & Style • Developed in the early to mid 1940’s • Medium to fast tempos • Rapid chord progressions / changes • Instrumental “virtuosity” • Simple to complex harmony - altered chords / substitutions • Dominant syncopation of rhythms • New melodies over existing chord changes - Contrafacts Scales & Arpeggios • Scales and arpeggios are the building blocks for harmony • Use of the half-step interval and rapid arpeggiation are characteristic of bebop playing • Because bebop is often played at a fast tempo with rapidly changing chords, it’s crucial to practice your scales and arpeggios in ALL KEYS! Scales & Arpeggios • Scales you should be familiar with: • Major Scale - Pentatonic: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 • Minor Scales - Pentatonic: 1, b3, 4, 5, b7; Natural Minor, Dorian Minor, Harmonic Minor, Melodic Minor • Dominant Scales - Mixolydian Mode, Bebop Scales, 5th Mode of Harmonic Minor (V7b9), Altered Dominant / Diminished Whole Tone (V7alt, b9#9b13), Dominant Diminished / Diminished starting with a half step (V7b9#9 with #11, 13) • Half-diminished scale - min7b5 (7th mode of major scale) • Diminished Scale - Starting with a whole step (WHWHWHWH) Scales & Arpeggios • Chords and Arpeggios to work in all keys: • Major triad, Maj6/9, Maj7, Maj9, Maj9#11 • Minor triad, m6/9, m7, m9, m11, minMaj7 • Dominant 7ths • Natural extensions - 9th, 13th -

European Jazz Orchestra 2011 Bios-Updated 14022011

DSI Swinging Europe European Jazz Orchestra 2011 European Jazz Orchestra Draft biographies / Personal notes of 14th February 2011 Self-Governing Institution Swinging Europe Conductor Nørregade 7D DK-7400 Jere Laukkanen Herning Finnish Denmark Born 1963 in Helsinki, Finland T.: +45 6094 1236 Currently based in Helsinki, Finland E: [email protected] W: www.swinging-europe.dk Although Jere Laukkanen is probably best known for his work in combining modern jazz and Afro-Cuban rhythms, he has a long history of various musical activities. As a youth he played SE/CVR Nr.:32978665 flute and alto sax, studied drums, recorded as a singer, guitar player and bandleader, and Bank: Handelsbanken then commenced professional studies on the bass at the Helsinki Pop & Jazz Conservatory. Reg.: 7621 Laukkanen later concentrated on composing and arranging, with Henrik Otto Donner ao. as Konto Nr.: 2137244 his teacher, and studied conducting with Maria Schneider. Laukkanen continued his studies at the Sibelius Academy, where he earned a Master of Music degree in Jazz Composition. Currently he is writing a doctoral dissertation on jazz rhythm at the Doctoral Study Program of Music and Drama in Finland. Jere Laukkanen is currently working as Head of Degree Programme and Senior Lecturer at the Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, Degree Programme in Pop and Jazz Music. He is a much sought-after arranger, composer and conductor, and has written for all major Finnish television channels and numerous orchestras, including UMO Jazz Orchestra, Vantaa Pops Orchestra, and Lahti Symphony Orchestra. Besides his own band, Jere Laukkanen Afro-Cuban Jazz Orchestra, for which he is the sole composer and arranger, he has conducted jazz orchestras like UMO, Berklee Jazz Composers’ Big Band (USA), Radio Romania Big Band, and Estonian Dream Big Band. -

Towards a Generative Framework for Understanding Musical Modes

Table of Contents Introduction & Key Terms................................................................................1 Chapter I. Heptatonic Modes.............................................................................3 Section 1.1: The Church Mode Set..............................................................3 Section 1.2: The Melodic Minor Mode Set...................................................10 Section 1.3: The Neapolitan Mode Set........................................................16 Section 1.4: The Harmonic Major and Minor Mode Sets...................................21 Section 1.5: The Harmonic Lydian, Harmonic Phrygian, and Double Harmonic Mode Sets..................................................................26 Chapter II. Pentatonic Modes..........................................................................29 Section 2.1: The Pentatonic Church Mode Set...............................................29 Section 2.2: The Pentatonic Melodic Minor Mode Set......................................34 Chapter III. Rhythmic Modes..........................................................................40 Section 3.1: Rhythmic Modes in a Twelve-Beat Cycle.....................................40 Section 3.2: Rhythmic Modes in a Sixteen-Beat Cycle.....................................41 Applications of the Generative Modal Framework..................................................45 Bibliography.............................................................................................46 O1 O Introduction Western -

All-Jazz Real Book

All-Jazz Real Book Title Composer / As Played By Page 2 Degrees East, 3 Degrees West John Lewis 1 2 Down, 1 Across Kenny Garrett 2 A Cor Do Por-Do-Sol Ivan Lins & Celso Viafora 4 Adoracion Eddie Palmieri & Ishmael Quintana 6 Afternoon In Paris John Lewis 11 All Is Quiet Bob Mintzer & Kurt Elling 12 Amanda Duke Pearson 14 Antigua Antonio Carlos Jobim 16 April Mist Tom Harrell 18 At Night Marc Copland 20 At The Close Of The Day Fred Hersch 22 Ayer Y Hoy Dario Eskenazi 24 Azule Serape Victor Feldman 32 Beatrice Sam Rivers 35 The Beauty Of All Things Laurence Hobgood & Kurt Elling 36 Beauty Secrets Kenny Werner 40 Bebe Hermeto Pascoal 42 Being Cool (Aviao) Djavan 44 Beiral Djavan 46 Big J John Scofield 49 Blue Matter John Scofield 50 Blue Seven Sonny Rollins 53 Blues For Pablo Gil Evans 54 Bohemia After Dark Oscar Pettiford 58 Borzeguim Antonio Carlos Jobim 60 Brazilian Suite Michel Petrucciani 68 Broken Wing Richie Beirach 71 Butterfly Dreams Stanley Clarke & Neville Potter 72 Can't Take You Nowhere Tiny Kahn, Al Cohn & Dave Frishberg 74 Cantaloupe Island Herbie Hancock 76 Caprice Eddie Gomez 78 Chitlins Con Carne Kenny Burrell 79 Choro Das Aguas Ivan Lins & Vitor Martins 80 Chris Craft Alan Broadbent 82 Circle Dance Eddie Daniels 84 Congri Rebeca Mauleon 86 Continuacion Orlando "Maraca" Valle 94 Coralie Enrico Pieranunzi 102 Countdown John Coltrane 104 Crazeology Charlie Parker 105 Dance Of Denial Michael Philip Mossman 106 Dare The Moon Darmon Meader, Sara Krieger & Caprice Fox 114 1 All-Jazz Real Book Title Composer / As Played By Page Dark Territory Marc Copland 120 Desalento Chico Buarque 124 Don't Let It Go Vincent Herring 126 Down Miles Davis 128 Dr. -

Creative Music Studio Norman Granz Glen Hall Khan Jamal David Lopato Bob Mintzer CD Reviews International Jazz News Jazz Stories Remembering Bert Wilson

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC Creative Music Studio Norman Granz Glen Hall Khan Jamal David Lopato Bob Mintzer CD Reviews International jazz news jazz stories Remembering bert wilson Volume 39 Number 3 July Aug Sept 2013 romhog records presents random access a retrospective BARRY ROMBERG’S RANDOM ACCESS parts 1 & 2 “FULL CIRCLE” coming soon www.barryromberg.com www.itunes “Leslie Lewis is all a good jazz singer should be. Her beautiful tone and classy phrasing evoke the sound of the classic jazz singers like Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah aughan.V Leslie Lewis’ vocals are complimented perfectly by her husband, Gerard Hagen ...” JAZZ TIMES MAGAZINE “...the background she brings contains some solid Jazz credentials; among the people she has worked with are the Cleveland Jazz Orchestra, members of the Ellington Orchestra, John Bunch, Britt Woodman, Joe Wilder, Norris Turney, Harry Allen, and Patrice Rushen. Lewis comes across as a mature artist.” CADENCE MAGAZINE “Leslie Lewis & Gerard Hagen in New York” is the latest recording by jazz vocalist Leslie Lewis and her husband pianist Gerard Hagen. While they were in New York to perform at the Lehman College Jazz Festival the opportunity to record presented itself. “Leslie Lewis & Gerard Hagen in New York” featuring their vocal/piano duo is the result those sessions. www.surfcovejazz.com Release date August 10, 2013. Surf Cove Jazz Productions ___ IC 1001 Doodlin’ - Archie Shepp ___ IC 1070 City Dreams - David Pritchard ___ IC 1002 European Rhythm Machine - ___ IC 1071 Tommy Flanagan/Harold Arlen Phil Woods ___ IC 1072 Roland Hanna - Alec Wilder Songs ___ IC 1004 Billie Remembered - S. -

Digital Real Book, Part One

Digital Real Book, Part One TITLE COMPOSER / AS PLAYED BY (Anda Ven Y) Muévete Juan Formell (How Little It Matters) How Little We Know Philip Springer (Se Acabó) La Malanga Rudy Calzado (The Old Man from) The Old Country Nat Adderley, Curtis R. Lewis 1983 Eddie Palmieri 2 Degrees East, 3 Degrees West John Lewis A Cor Do Pôr-Do-Sol Ivan Lins A Face Like Yours Victor Feldman A Little Tear Eumir Deodato, Paulo Sergio Valle A Summer In San Francisco Hendrik Meurkens A Tune for Double "D" Mark Elf Afro Blue Mongo Santamaria After the Love Has Gone David Walter Foster, Jay Graydon, Bill Champlin Afternoon in Paris John Lewis Ain't Misbehavin' Harry Brooks, Thomas Waller All about Ronnie Joe Greer All Is Quiet Bob Mintzer Amanda Duke Pearson Amor Ivan Lins, Vitor Martins Anatelio (The Happy People) Airto Moreira Angel Eyes Matt Dennis Antigua Antonio Carlos Jobim Aparecida Ivan Lins, Mauricio Topajos April Mist Tom Harrell Arallué Rubén Blades Are You Real? Benny Golson At Night Marc Copland At the Close of the Day Fred Hersch Atras De Nos Richard Boukas Ayer Y Hoy (Yesterday and Today) Dario Eskenazi Azule Serape Victor Feldman Azure-Té Billy Davis Bags' Groove Milt Jackson Barbara Horace Silver Beautiful Love Egbert Anson Van Alstyne, Victor Young, Wayne King Beauty Secrets Kenny Werner Bebe Hermeto Pascoal Bebop Lives (Boplicity) Miles Davis Being Cool (Avião) Djavan Big Bertha Duke Pearson Big J John Scofield Black and Blue Harry Brooks, Thomas Waller Black Coffee Paul Francis Webster, Sonny Burke Blue Matter John Scofield Blues in the Closet -

A Transformational Approach to Jazz Harmony

A TRANSFORMATIONAL APPROACH TO JAZZ HARMONY Michael McClimon Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University January 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee Julian Hook, Ph.D. Kyle Adams, Ph.D. Blair Johnston, Ph.D. Brent Wallarab, M.M. December 9, 2015 ii Copyright © 2016 Michael McClimon iii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the help of many others, each of whom deserves my thanks here. Pride of place goes to my advisor, Jay Hook, whose feedback has been invaluable throughout the writing process, and whose writing stands as a model of clarity that I can only hope to emulate. Thanks are owed to the other members of my committee as well, who have each played important roles throughout my education at Indiana: Kyle Adams, Blair Johston, and Brent Wallarab. Thanks also to Marianne Kielian-Gilbert, who would have served on the committee were it not for the timing of the defense during her sabbatical. I would like to extend my appreciation to Frank Samarotto and Phil Ford, both of whom have deeply shaped the way I think about music, but have no official role in the dissertation itself. I am grateful to the music faculty of Furman University, who inspired my love of music theory as an undergraduate and have more recently served as friends and colleagues during the writing process.