The Jazz and Improvised Music Scene in Vienna After Ossiach (1971-2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Licht Ins Dunkel“

O R F – J a h r e s b e r i c h t 2 0 1 3 Gemäß § 7 ORF-Gesetz März 2014 Inhalt INHALT 1. Einleitung ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Grundlagen........................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Das Berichtsjahr 2013 ......................................................................................................... 8 2. Erfüllung des öffentlich-rechtlichen Kernauftrags.................................................................. 15 2.1 Radio ................................................................................................................................... 15 2.1.1 Österreich 1 ............................................................................................................................ 16 2.1.2 Hitradio Ö3 ............................................................................................................................. 21 2.1.3 FM4 ........................................................................................................................................ 24 2.1.4 ORF-Regionalradios allgemein ............................................................................................... 26 2.1.5 Radio Burgenland ................................................................................................................... 27 2.1.6 Radio Kärnten ........................................................................................................................ -

Here I Played with Various Rhythm Sections in Festivals, Concerts, Clubs, Film Scores, on Record Dates and So on - the List Is Too Long

MICHAEL MANTLER RECORDINGS COMMUNICATION FONTANA 881 011 THE JAZZ COMPOSER'S ORCHESTRA Steve Lacy (soprano saxophone) Jimmy Lyons (alto saxophone) Robin Kenyatta (alto saxophone) Ken Mcintyre (alto saxophone) Bob Carducci (tenor saxophone) Fred Pirtle (baritone saxophone) Mike Mantler (trumpet) Ray Codrington (trumpet) Roswell Rudd (trombone) Paul Bley (piano) Steve Swallow (bass) Kent Carter (bass) Barry Altschul (drums) recorded live, April 10, 1965, New York TITLES Day (Communications No.4) / Communications No.5 (album also includes Roast by Carla Bley) FROM THE ALBUM LINER NOTES The Jazz Composer's Orchestra was formed in the fall of 1964 in New York City as one of the eight groups of the Jazz Composer's Guild. Mike Mantler and Carla Bley, being the only two non-leader members of the Guild, had decided to organize an orchestra made up of musicians both inside and outside the Guild. This group, then known as the Jazz Composer's Guild Orchestra and consisting of eleven musicians, began rehearsals in the downtown loft of painter Mike Snow for its premiere performance at the Guild's Judson Hall series of concerts in December 1964. The orchestra, set up in a large circle in the center of the hall, played "Communications no.3" by Mike Mantler and "Roast" by Carla Bley. The concert was so successful musically that the leaders decided to continue to write for the group and to give performances at the Guild's new headquarters, a triangular studio on top of the Village Vanguard, called the Contemporary Center. In early March 1965 at the first of these concerts, which were presented in a workshop style, the group had been enlarged to fifteen musicians and the pieces played were "Radio" by Carla Bley and "Communications no.4" (subtitled "Day") by Mike Mantler. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON School of Humanities: Music Making the weather in contemporary jazz: an appreciation of the musical art of Josef Zawinul by Alan Cooper Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2012 i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT Making the weather in contemporary jazz: an appreciation of the musical art of Josef Zawinul by Alan Cooper Josef Zawinul (1932-2007) holds a rare place in the world of jazz in view of the fact that as a European he forged a long and distinguished musical career in America. Indeed, from a position of relative obscurity when he arrived in New York in 1959, he went on to become one of contemporary jazz’s most prolific and commercially successful composers. The main focus of this dissertation will be Zawinul’s rise to prominence in American jazz during the 1960s and 1970s. -

Named Football Coach and Who Can Forget the Role Vic Gatto Played Last Friday Afternoon Marked Ihe Beginning of in the Dream Game Vs

Bates College SCARAB The aB tes Student Archives and Special Collections 4-5-1973 The aB tes Student - volume 99 number 23 - April 5, 1973 Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student Recommended Citation Bates College, "The aB tes Student - volume 99 number 23 - April 5, 1973" (1973). The Bates Student. 1668. http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student/1668 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aB tes Student by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2V3 THIS IS THE LAST ISSUE OF THE STUDENT. IF YOU ENJOYED IT PLEASE TUNE IN NEXT SEPTEMBER. BUT IN THE MEANTIME, CATCH OUR SUMMER REPLACEMENT, "ASK THE DEANS" APPEARING??? Harvard Great Named Football Coach And who can forget the role Vic Gatto played Last Friday afternoon marked Ihe beginning of in the Dream Game vs. Yale that year, when a new era in Bales College football fortunes as Harvard scored 16 points in the final I minute of Victor E. Gatto, Jr. was named Head Football play to bring off a 29-29 tie to preserve Harvard's Coacli by President Thomas Hedley Reynolds. 1st undefeated season in 48 years!!! Matched that According to the President. "I think we have day against Yale's Calvin Hill, Gatto scored the chosen the young man with the greatest potential final touchdown of the game! as a football coach in New England." The honors were many for this fierce A total of over 80 applicants filed briefs with competitor from Needham, Mass. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White Home Address: 23271 Rosewood Oak Park, MI 48237 (917) 273-7498 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.walterwhite.com EDUCATION Banff Centre of Fine Arts Summer Jazz Institute – Advanced study of jazz performance, improvisation, composition, and 1985-1988 arranging. Performances with Dave Holland. Cecil Taylor, Muhal Richard Abrahms, David Liebman, (July/August) Richie Beirach, Kenny Wheeler, Pat LaBarbara, Julian Priester, Steve Coleman, Marvin Smith. The University of Miami 1983-1986 Studio Music and Jazz, Concert Jazz Band, Monk/Mingus Ensemble, Bebop Ensemble, ECM Ensemble, Trumpet. The Juilliard School 1981-1983 Classical Trumpet, Orchestral Performance, Juilliard Orchestra. Interlochen Arts Academy (High School Grades 10-12) 1978-1981 Trumpet, Band, Orchestra, Studio Orchestra, Brass Ensemble, Choir. Interlochen Arts Camp (formerly National Music Camp) 8-weeks Summers, Junior Orchestra (principal trumpet), Intermediate Band (1st Chair), Intermediate Orchestra (principal), 1975- 1979, H.S. Jazz Band (lead trumpet), World Youth Symphony Orchestra (section 78-79, principal ’81) 1981 Henry Ford Community College Summer Jazz Institute Summer Classes in improvisation, arranging, small group, and big band performance. 1980 Ferndale, Michigan, Public Schools (Grades K-9) 1968-1977 TEACHING ACCOMPLISHMENTS Rutgers University, Artist-in-residence Duties included coaching jazz combos, trumpet master 2009-2010 classes, arranging classes, big band rehearsals and sectionals, private lessons, and five performances with the Jazz Ensemble, including performances with Conrad Herwig, Wynton Marsalis, Jon Faddis, Terrell Stafford, Sean Jones, Tom ‘Bones’ Malone, Mike Williams, and Paquito D’Rivera Newark, NY, High School Jazz Program Three day residency with duties including general music clinics and demonstrations for primary and secondary students, coaching of Wind Ensemble, Choir, Jan 2011 Jazz Vocal Ensemble, and two performances with the High School Jazz Ensemble. -

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation The Mari Lwyd and the Horse Queen: Palimpsests of Ancient ideas A dissertation submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Celtic Studies 2012 Lyle Tompsen 1 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Abstract The idea of a horse as a deity of the land, sovereignty and fertility can be seen in many cultures with Indo-European roots. The earliest and most complete reference to this deity can be seen in Vedic texts from 1500 BCE. Documentary evidence in rock art, and sixth century BCE Tartessian inscriptions demonstrate that the ancient Celtic world saw this deity of the land as a Horse Queen that ruled the land and granted fertility. Evidence suggests that she could grant sovereignty rights to humans by uniting with them (literally or symbolically), through ingestion, or intercourse. The Horse Queen is represented, or alluded to in such divergent areas as Bronze Age English hill figures, Celtic coinage, Roman horse deities, mediaeval and modern Celtic masked traditions. Even modern Welsh traditions, such as the Mari Lwyd, infer her existence and confirm the value of her symbolism in the modern world. 2 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Table of Contents List of definitions: ............................................................................................................ 8 Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

FAT – Fabulous Austrian Trio

FAT – Fabulous Austrian Trio "Alex Machacek's music starts where other music ends" sagte John McLaughlin über Alex Machacek’s Album, auf dem neben Terry Bozzio auch erstmals FAT zu hören ist, auch wenn dies FAT damals noch nicht bewusst war. FAT, kurz für Fabulous Austrian Trio, formierte sich 2004, dem Jahr, in dem Europas „Guitar Newcomer 98“ von Wien nach Los Angeles auswanderte. Alex nutzte seine Europareisen als Lebenserhaltungsmaßnahme für die Band und 2010 veröffentlichten sie ihr erstes Album „FAT“. Bei den BMW World Jazz Awards 2015 staubten sie den 2. Platz ab und mit “Living the Dream” setzten Alex Machacek, Bassist Raphael Preuschl und Schlagzeuger Herbert Pirker noch eins drauf. Das Zusammentreffen der Band in LA 2016 wurde nicht nur zum Proben, Recorden und Tischtennis spielen genutzt, FAT konzertierte auch im legendären Baked Potato. Im letzten Sommer gastierten sie unter anderem beim OutreachFestival, dem Jazz Festival Leibnitz und dem Bayrischen Rundfunk. Das neue Album ist bereits mitten im Entstehungsprozess und im Februar verschlägt es FAT wieder über den Atlantik zur „Cruise to the Edge“. "Maybe it's the inevitable wisdom of age, with Machacek now in his early 40s, but as impressive as "Living the Dream" is, and as much as it fits comfortably in his overall discography, it's the album where, despite its many twists and turns, harmonic, melodic and rhythmic surprises, and the evolving chemistry of FAT, it's also the album where all three musicians come together with a sense of nothing left to prove. And it's that very comfort level with each other, and that very feeling of maturity that makes "Living the Dream" an even better record than the superb "FAT"...and one of the very best in Machacek's growing discography." John Kelman/AllAboutJazz "Alex Machacek's music starts where other music ends" John McLaughlin's reaction to "[sic]" Alex Europareisen wurden zur Lebenserhaltungsmaßnahme für das Trio und so reifte genug Material für das erste Album der Band “FAT” (2010). -

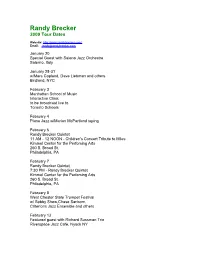

2009 Tour Dates

Randy Brecker 2009 Tour Dates Website: http://www.randybrecker.com/ Email: [email protected] January 20 Special Guest with Saleno Jazz Orchestra Salerno, Italy January 28-31 w/Marc Copland, Dave Liebman and others Birdland, NYC February 3 Manhattan School of Music Interactive Clinic to be broadcast live to Toronto Schools February 4 Piano Jazz w/Marian McPartland taping February 6 Randy Brecker Quintet 11 AM - 12 NOON - Children's Concert Tribute to Miles Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 7 Randy Brecker Quintet 7:30 PM - Randy Brecker Quintet Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 8 West Chester State Trumpet Festival w/ Bobby Shew,Chase Sanborn, Criterions Jazz Ensemble and others February 13 Featured guest with Richard Sussman Trio Riverspace Jazz Cafe, Nyack NY February 15 Special guest w/Dave Liebman Group Baltimore, Maryland February 20 - 21 Special guest w/James Moody Quartet Burmuda Jazz Festival March 1-2 Northeastern State Universitry Concert/Clinic Tahlequah, Oklahoma March 6-7 Concert/Clinic for Frank Foster and Break the Glass Foundation Sandler Perf. Arts Center Virginia Beach, VA March 17-25 Dates TBA European Tour w/Lynne Arriale quartet feat: Randy Brecker, Geo. Mraz A. Pinciotti March 27-28 Temple University Concert/Clinic Temple,Texas March 30 Scholarship Concert with James Moody BB King's NYC, NY April 1-2 SUNY Purchase Concert/Clinic with Jazz Ensemble directed by Todd Coolman April 4 Berks Jazz Festival w/Metro Special Edition: Chuck Loeb, Dave Weckl, Mitch Forman and others April 11 w/ Lynne Arriale Jazz Quartet Ft. -

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003 The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire by Bonny Kathleen Winston, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2003 Dedication This dissertation would not have been completed without all of the love and support from professors, family, and friends. To all of my dissertation committee for their support and help, especially John Geringer for his endless patience, Betty Mallard for her constant inspiration, and Martha Hilley for her underlying encouragement in all that I have done. A special thanks to my family, who have been the backbone of my music growth from childhood. To my parents, who have provided unwavering support, and to my five brothers, who endured countless hours of before-school practice time when the piano was still in the living room. Finally, a special thanks to my hall-mate friends in the school of music for helping me celebrate each milestone of this research project with laughter and encouragement and for showing me that graduate school really can make one climb the walls in MBE. The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire Publication No. ________________ Bonny Kathleen Winston, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2003 Supervisor: John M. Geringer The purpose of this dissertation was to create an on-line database for intermediate piano repertoire selection. -

Performers and Teachers 2015 South African

PERFORMERS AND TEACHERS 2015 SOUTH AFRICAN Keenan Ahrends (Guitar) studied jazz guitar at the University of Cape Town and the Norwegian Academy of Music. He was selected for the National Youth Jazz Band in 2006 and has collaborated with established musicians such as Andile Yenana, Afrika Mkhize, Buddy Wells and Kevin Gibson amongst others. Ahrends is a regular performer on the Cape Town music scene and has been commissioned to compose works for the Goema Orchestra and regularly per- forms original compositions with his own Trio and Quartet. www.soundcloud.com/keenan-ahrends Alistair Andrews (Bass) lectured Music Technology at UCT, and is involved in the Music Education and Apple Mac and Music Technology department at Paul Bothner Music. As a Warwick-endorsed bass player, he has been a regular on the Cape Town and South African jazz scene for almost 30 years, performing with many of South Africa’s top musi- cians in numerous settings. www.alistair.co.za www.myspace.com/alistairandrews Kelly Bell (Trombone) was selected for the National Youth Big Band in 2002 and 2003. She teaches Music at Sans Souci in Cape Town, where she conducts the Jazz Band. Justin Bellairs (Sax) was selected for the National Schools’ Jazz Band in 2007 and National Youth Jazz Band in 2009 and 2012. He studied jazz at the UCT College of Music, spent a year at The Norwegian Academy of Music in Oslo and obtained a Masters degree in music performance from Rhodes University. He now performs professionally in a variety of musical productions and shows including the Cape Philharmonic Orchestra, Mike Campbell Big Band, Kesivan & The Lights and The Shane Cooper Quintet. -

Hal Leonard Piano Selections from the NFMC Festivals Bulletin 2014

Hal Leonard Piano Selections from the NFMC Festivals Bulletin 2014–2015–2016 Please see your favorite music retailer to purchase these publications. Please see www.halleonard.com for complete descriptions and table of contents. Please contact the National Federation of Music Clubs for further information on rules for the National Festivals. www.nfmc-music.org Prices, contents, and availability subject to change without notice and may vary outside the U.S.A. Order Qty Item Description Composer Publisher Price Piano Solo Event Pre - Primary Class Piano Solo 416896 Extra Special Day Miller, Carolyn Willis Music $ 2.99 Primary Class I Piano Solos 416850 Barnyard Strut Austin, Glenda Willis Music $ 2.99 296840 Just for Kids Rejino, Mona Hal Leonard $ 7.99 Monday Mornin' Blues The Tooth Fairy 416933 The Perceptive Detective Miller, Carolyn Willis Music $ 2.99 296868 Things Go Bump Klose, Carol Hal Leonard $ 2.99 Primary Class II Piano Solos 296830 Chimichanga Cha-Cha Linn, Jennifer Hal Leonard $ 2.99 296840 Just for Kids Rejino, Mona Hal Leonard $ 7.99 Let's Go On Vacation Pepperoni Pizza Primary Class III Piano Solos 416819 Drifting Sunset Clouds Hartsell, Randall Willis Music $ 2.99 416878 Mini Toccata Baumgartner, Eric Willis Music $ 2.99 102595 PBJ Blues Klose, Carol Hal Leonard $ 2.99 Primary Class IV Piano Solos 296835 Alley Cat Caper Cruse, Hannah Hal Leonard $ 2.99 296849 Blues, Jazz, Rock & Rags, Book 1 Watts, Jennifer & Mike Hal Leonard $ 8.99 Lazy Daisy Raggin' Around Sneakin' Cake 296854 Footprints in the Snow Linn, Jennifer Hal -

Jazz Various the Swing Years (1936- 46) RD4-21- 1/6 Reader's Digest

Jazz Various The Swing Years (1936- RD4-21- Reader's VG/ 6 Disc Box 46) 1/6 Digest (RCA VG+ Set Custom) Various In the Groove with the RD4-45- Reader's VG+ 6 Disc Box Info Kings Of Swing 1/6 Digest (RCA Set Packet Custom) Various The Great Band Era RD4-21- Reader's VG/ 10 Disc Cover (1936-1945) 1/9 Digest (RCA VG+ Box Set and Disc Custom) 10 Missing Various Big Band Collection QUSP- Quality VG-/ Box Set vol.1 5002 Special VG Missing Products Box Various Big Band Collection vol. QUSP- Quality VG/ Box Set 2 5002 Special VG+ Missing Products Box Various Big Band Collection vol. QUSP- Quality VG/ Box Set 3 5002 Special VG+ Missing Products Box The Cannonball Mercy, Mercy, Mercy T-2663 Capitol VG/ Live at Adderley Quintet VG+ “The Club” The Cannonball Country Preacher SKA0-8- Capitol VG/ Gatefold Adderley Quintet 0404 VG+ The Cannonball Why Am I Treated So ST-2617 Capitol VG-/ Adderley Quintet Bad! VG The Cannonball Accent On Africa ST-2987 Capitol VG/ Adderley Quintet VG+ The Cannonball Cannonball Adderly with ST-2877 Capitol VG-/ Adderley and the Sergio Mendes & The VG Bossa Rio Sextet Bossa Rio Sextet with Sergio Mendes Nat King Cole The Swingin' Moods Of DQBO- Capitol VG/ 2 Disc Nat King Cole 91278 VG+ Gatefold Nat King Cole The Unforgettable Nat ST-2558 Capitol VG-/ King Cole Sings The VG Great Songs Nat King Cole Ramblin' Rose ST-1793 Capitol VG 1 Jazz Nat King Cole Thank You, Pretty Baby ST-2759 Capitol VG/ VG+ Nat King Cole The Beautiful Ballads ST-2820 Capiol VG/ VG+ Nancy Williams From Broadway With T-2433 Capitol VG/ Love VG+ Nancy