Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morris Matters Vol 32 Issue 2

Morris Matters Volume 32 Number 2 July 2013 Contents of Volume 32 Number 2 Image of Morris 3 by Tony Forster History of Clog Making in Lancashire 6 by Michael Jackson A Very English Winter – a Review 7 by George Frampton Berkshire Bedlam at the Marlboro Ale 2013 9 by Malcolm Major We Have Our Uses! – The Morris in Conceptual Art - Observations 10 by George Frampton The Morris Wars 12 by Derek Schofield Where Have All the Researchers Gone? 15 by George Frampton Dance with Dommett – Take 2 18 by Denise Allen American Film Archive 19 by Jan Elliott DERT 2013 – we are the champions! 20 by Sally Wearing Updating Morris: the leaked report 23 by Long Lankin Roger Ring Morris 24 by Andy Morris Matters is published twice a year (January and July) by Beth Neill with thanks to Jill Griffiths for proofreading. Subscriptions are £6 for two issues (£8 outside EU countries). Please make cheques payable to Morris Matters or ask for BACS details. 27 Nortoft Road, Chalfont St Peter, Bucks SL9 0LA Reviews or other contributions always welcome [[email protected]] - 1 Morris Matters Volume 32 Number 2 July 2013 Editorial There is a fair bit in here about researchers past and present and who will be carrying this on in the future… there always seems to be something new to be unearthed both in the UK and abroad. The morris world seems to be very active over in the USA & Canada – both in research, and in dancing. As I write I know that Morris Offspring are heading over the water and joining forces with Maple Morris for a series of performances. -

Licht Ins Dunkel“

O R F – J a h r e s b e r i c h t 2 0 1 3 Gemäß § 7 ORF-Gesetz März 2014 Inhalt INHALT 1. Einleitung ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Grundlagen........................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Das Berichtsjahr 2013 ......................................................................................................... 8 2. Erfüllung des öffentlich-rechtlichen Kernauftrags.................................................................. 15 2.1 Radio ................................................................................................................................... 15 2.1.1 Österreich 1 ............................................................................................................................ 16 2.1.2 Hitradio Ö3 ............................................................................................................................. 21 2.1.3 FM4 ........................................................................................................................................ 24 2.1.4 ORF-Regionalradios allgemein ............................................................................................... 26 2.1.5 Radio Burgenland ................................................................................................................... 27 2.1.6 Radio Kärnten ........................................................................................................................ -

PH 'Wessex White Horses'

Notes from a Preceptor’s Handbook A Preceptor: (OED) 1440 A.D. from Latin praeceptor one who instructs, a teacher, a tutor, a mentor “A horse, a horse and they are all white” Provincial Grand Lodge of Wiltshire Provincial W Bro Michael Lee PAGDC 2017 The White Horses of Wessex Editors note: Whilst not a Masonic topic, I fell Michael Lee’s original work on the mysterious and mystical White Horses of Wiltshire (and the surrounding area) warranted publication, and rightly deserved its place in the Preceptors Handbook. I trust, after reading this short piece, you will wholeheartedly agree. Origins It seems a perfectly fair question to ask just why the Wiltshire Provincial Grand Lodge and Grand Chapter decided to select a white horse rather than say the bustard or cathedral spire or even Stonehenge as the most suitable symbol for the Wiltshire Provincial banner. Most continents, most societies can provide examples of the strange, the mysterious, that have teased and perplexed countless generations. One might include, for example, stone circles, ancient dolmens and burial chambers, ley lines, flying saucers and - today - crop circles. There is however one small area of the world that has been (and continues to be) a natural focal point for all of these examples on an almost extravagant scale. This is the region in the south west of the British Isles known as Wessex. To our list of curiosities we can add yet one more category dating from Neolithic times: those large and mysterious figures dominating our hillsides, carved in the chalk and often stretching in length or height to several hundred feet. -

Vernon Watkins Family Letters, (NLW MS 23185D.)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Vernon Watkins family letters, (NLW MS 23185D.) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 09, 2017 Printed: May 09, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/vernon-watkins-family-letters archives.library .wales/index.php/vernon-watkins-family-letters Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Vernon Watkins family letters, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points ............................................................................................................... 5 -

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: Population Decline and Ritual Landscapes in Antonine London

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: population decline and ritual landscapes in Antonine London In this paper I turn my attention to the changes that took place in London in the mid to late second century. Until recently the prevailing orthodoxy amongst students of Roman London was that the settlement suffered a major population decline in this period. Recent excavations have shown that not all properties were blighted by abandonment or neglect, and this has encouraged some to suggest that the evidence for decline may have been exaggerated.1 Here I wish to restate the case for a significant decline in housing density in the period circa AD 160, but also draw attention to evidence for this being a period of increased investment in the architecture of religion and ceremony. New discoveries of temple complexes have considerably improved our ability to describe London’s evolving ritual landscape. This evidence allows for the speculative reconstruction of the main processional routes through the city. It also shows that the main investment in ceremonial architecture took place at the very time that London’s population was entering a period of rapid decline. We are therefore faced with two puzzling developments: why were parts of London emptied of houses in the middle second century, and why was this contraction accompanied by increased spending on religious architecture? This apparent contradiction merits detailed consideration. The causes of the changes of this period have been much debated, with most emphasis given to the economic and political factors that reduced London’s importance in late antiquity. These arguments remain valid, but here I wish to return to the suggestion that the Antonine plague, also known as the plague of Galen, may have been instrumental in setting London on its new trajectory.2 The possible demographic and economic consequences of this plague have been much debated in the pages of this journal, with a conservative view of its impact generally prevailing. -

The Boar's Head and Yule Log Festival

The Boar’s Head and Yule Log Festival January 3 & 4, 2015 IN THE CITY OF CINCINNATI The Festival’s roots. Oxford University’s Queens College, The Boar’s Head Tradition Oxford, England. From Medieval Terrors to Modern Magic 1340 - 2015 The Boar’s Head Festival is probably the oldest continuing festival of the Christmas season. When it came to Cincinnati in 1940, it already had a 600-year history. The pageant’s roots go back to medieval times when wild boars were the most dangerous animals in European forests. They were a menace to humans and were hunted as public enemies. Like our Thanksgiving turkey, roasted boar was a staple of medieval banquet tables—symbolizing the triumph of man over ferocious beast. As Christian beliefs overtook pagan customs in Europe, the presentation of a boar’s head at Christmas time came to symbolize the triumph of the Christ Child over the evils of the world. The festival we know today originated at Queen’s College, Oxford, England, in 1340. Legend has it that a scholar was studying a book of Aristotle while walking through the forest on his way to Christmas Mass. Suddenly he was confronted by an angry boar. Having no other weapon, the quick-witted student rammed his metal-bound philosophy book down the throat of the charging animal and the boar choked to death. That night, the beast’s head, finely dressed and garnished, was carried in procession into the dining room accompanied by carolers. By 1607, a similar ceremony was being celebrated at St. John’s College, Cambridge. -

The Mari Lwyd the Mari Lwyd

Lesson Aims • Learning about the Hen Galan tradition. • Discuss what people in the past did to celebrate and wish luck for the year to come. The Mari Lwyd The Mari It was a Lwyd was one This was part of the wassailinghorse’s of the strangest skull tradition.traditions People of the believed that the Mari Lwyd would bring goodcovered luck in Hen Galan a sheet, for (Newthe year Year). to come. They would celebrate during Decemberribbons and and January. bells. The skull was placed on a pole so that the person under the sheet would be able to open and close the mouth! The Battle The group would try to gain access to a house by singing a verse. This was called ՙpwnco՚. The homehold would then answer with their own rhyme in a fake battle to try to outwit the Mari Lwyd. Once the battle was at an end they would allow the Mari Lwyd and the crew into the house, where they would enjoy refreshments. They would then go from house to house, repeating these actions. Some Verses of the Mari Lwyd Song Outside Group Household Group Wel dyma ni’n dwad, O cerwch ar gered, gyfeillion diniwad, Mae’ch ffordd yn agored, I ofyn am gennad i ganu. Mae’ch ffordd yn agored nos heno. Outside Group Outside Group Os na chawn ni gannad, Nid awn ni ar gered, Rhowch glywad ar ganiad, Heb dorri ein syched, Pa fodd ma’r ‘madawiad nos heno. Heb dorri ein sychad nos heno. Outside Group Household Group Ma’ Mari Lwyd yma, Rhowch glywad, wyr ddoethion, A sêr a rhubana, Pa faint y’ch o ddynion, Yn werth i roi gola nos heno. -

Community Carol Sing Deck the Halls I Saw Three Ships

COMMUNITY CAROL SING DECK THE HALLS I SAW THREE SHIPS TABLE Deck the halls with boughs of holly, I saw three ships come sailing in, Fa la la la la, la la la la. On Christmas day, On Christmas day. OF CONTENTS Tis the season to be jolly... I saw three ships come sailing in, Don we now our gay apparel... On Christmas day in the morning. DECK THE HALLS page 3 Troll the ancient Yuletide carol... And what was in those ships all three… The Virgin Mary and Christ were there… O COME, ALL YE FAITHFUL page 3 See the blazing Yule before us... Pray, whither sailed those ships all I SAW THREE SHIPS page 3 Strike the harp and join the chorus... three.. Follow me in merry measure... O they sailed into Bethlehem… HERE WE COME A-WASSAILING page 3 While I tell of Yuletide treasure... page 4 IT CAME UPON A MIDNIGHT CLEAR Fast away the old year passes, HERE WE COME A-WASSAILING Hail the new, ye lads and lasses... HARK! THE HERALD ANGELS SING page 4 Here we come a-wassailing Among Sing we joyous, all together... the leaves so green; Here we come GOD REST YE MERRY GENTLEMEN page 5 Heedless of the wind and weather... a-wandering, So fair to be seen. RUDOLPH THE RED-NOSED REINDEER page 5 Chorus: Love and joy come to you, O COME ALL YE FAITHFUL JINGLE BELLS page 6 And to you our wassail, too. O come all ye faithful, And God bless you and JINGLE BELL ROCK page 6 joyful and triumphant. -

The Quarterly Magazine of the Thanet Branch of the Campaign for Real Ale

Fourth Quarter 2018 Free ALE The Quarterly Magazine of the Thanet Branch of the Campaign for Real Ale Inside this issue: Hop hoddening AoT’s Brighton run Social secretary’s blog A long lunch in St Albans Enjoying the beers of Tallinn On the Thanet Loop bus route ALE of Thanet A view from the chair After two years in the chair, this will probably be my last offering to you, not because I haven’t enjoyed my time, but as I currently just have too much on my plate, and now feels the right time to pass the gavel on, although I will (hopefully) remain on the committee and in my role as the Beer Festival Organiser. We are a strong Branch with over 500 members, if one of those members is you, please come along to our Annual General Meeting to be held on Saturday 19th January 2019 at The Bradstow Mill, 11.45 for a 12:00 prompt start. This is your opportunity to becoming involved in your Branch, to help us move forward, to celebrate and enjoy the excellent Re- al Ale and Real Cider that some of our local amazing establishments. Aside from the Branch Committee, we are also specifically looking for someone who could put together the Beer Festival Programme, including seeking advertisers and arranging the printing – could this be you? One the difficult tasks I have had this year is working with the Beer Festival Committee to ensure that we have a Festival in 2019. We had been in a really lucky position that for a considerable time we have had a very, very good rate when we hired the Winter Gardens, and due to the situa- tion, they are in, they had to review our hire, and after much number crunching and negotiation we have managed to secure the venue. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

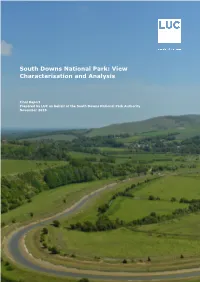

View Characterisation and Analysis

South Downs National Park: View Characterisation and Analysis Final Report Prepared by LUC on behalf of the South Downs National Park Authority November 2015 Project Title: 6298 SDNP View Characterisation and Analysis Client: South Downs National Park Authority Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by Director V1 12/8/15 Draft report R Knight, R R Knight K Ahern Swann V2 9/9/15 Final report R Knight, R R Knight K Ahern Swann V3 4/11/15 Minor changes to final R Knight, R R Knight K Ahern report Swann South Downs National Park: View Characterisation and Analysis Final Report Prepared by LUC on behalf of the South Downs National Park Authority November 2015 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 43 Chalton Street London Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Bristol Registered Office: Landscape Management NW1 1JD Glasgow 43 Chalton Street Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Edinburgh London NW1 1JD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper LUC BRISTOL 12th Floor Colston Tower Colston Street Bristol BS1 4XE T +44 (0)117 929 1997 [email protected] LUC GLASGOW 37 Otago Street Glasgow G12 8JJ T +44 (0)141 334 9595 [email protected] LUC EDINBURGH 28 Stafford Street Edinburgh EH3 7BD T +44 (0)131 202 1616 [email protected] Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background to the study 1 Aims and purpose 1 Outputs and uses 1 2 View patterns, representative views and visual sensitivity 4 Introduction 4 View -

Spring 2019/111

№ 111 Spring 2019 THE OLDEST AND LARGEST SOCIETY DEVOTED TO THE HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ANCIENT COUNTY OF KENT Wrotham Sheerness East Farleigh A straight-tusked elephant From medieval palace The Royal Dockyard: MAAG update Found at Upnor in 1911 garden to bowling green Where are we now? 05 18 24 28 ROCHESTER CATHEDRAL’S FRAGMENTS OF HISTORY President Hon. Editor Dr Gerald Cramp Terry G. Lawson [email protected] Vice Presidents Mr L.M. Clinch Hon. Curator Mr R.F. Legear Dr Elizabeth Blanning [email protected] Hon. General Secretary Clive Drew Hon. Librarian [email protected] Ruiha Smalley [email protected] Hon. Treasurer Barrie Beeching Press [email protected] Vacant Hon. Membership Secretary Newsletter Mrs Shiela Broomfield Richard Taylor [email protected] [email protected] WELCOME FROM THE EDITOR Welcome to the Spring 2019 Newsletter. skills in the process, to survey approximately 250,000 square metres of agricultural land, the results of Following a relatively quiet winter, we have an issue which are a feature on pages 15–17 of this issue. packed with a variety of fieldwork, historical research projects and discussion. The Letters to the Editor For me, the best way to increase the Society’s section has taken off in this issue with members membership is continued engagement and learning commenting on previously featured articles; this – get people involved, try new activities, learn new extended discussion is a long-term aim of the skills and make contributions to our County’s fantastic Newsletter and one, I hope, the Membership continues.