Chord-Scale Networks in the Music and Improvisations of Wayne Shorter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Non-Heptatonic Modes

Tagg: Everyday Tonality II — 4. Non‐heptatonic modes 151 4. Non‐heptatonic modes If modes containing seven different scale degrees are heptatonic, eight‐note modes are octatonic, six‐note modes hexatonic, those with five pentatonic, while four‐ and three‐note modes are tetratonic and tritonic. Now, even though the most popular pentatonic modes are sometimes called ‘gapped’ because they contain two scale steps larger than those of the ‘church’ modes of Chapter 3 —doh ré mi sol la and la doh ré mi sol, for example— they are no more incomplete FFBk04Modes2.fm. 2014-09-14,13:57 or empty than the octatonic start to example 70 can be considered cluttered or crowded.1 Ex. 70. Vigneault/Rochon (1973): Je chante pour (octatonic opening phrase) The point is that the most widespread convention for numbering scale degrees (in Europe, the Arab world, India, Java, China, etc.) is, as we’ve seen, heptatonic. So, when expressions like ‘thirdless hexatonic’ occur in this chapter it does not imply that the mode is in any sense deficient: it’s just a matter of using a quasi‐global con‐ vention to designate a particular trait of the mode. Tritonic and tetratonic Tritonic and tetratonic tunes are common in many parts of the world, not least in traditional music from Micronesia and Poly‐ nesia, as well as among the Māori, the Inuit, the Saami and Native Americans of the great plains.2 Tetratonic modes are also found in Christian psalm and response chanting (ex. 71), while the sound of children chanting tritonic taunts can still be heard in playgrounds in many parts of the world (ex. -

Harmony Crib Sheets

Jazz Harmony Primer General stuff There are two main types of harmony found in modern Western music: 1) Modal 2) Functional Modal harmony generally involves a static drone, riff or chord over which you have melodies with notes chosen from various scales. It’s common in rock, modern jazz and electronic dance music. It predates functional harmony, too. In some types of modal music – for example in jazz - you get different modes/chord scale sounds over the course of a piece. Chords and melodies can be drawn from these scales. This kind of harmony is suited to the guitar due to its open strings and retuning possibilities. We see the guitar take over as a songwriting instrument at about the same time as the modes become popular in pop music. Loop based music also encourages this kind of harmony. It has become very common in all areas of music since the late 20th century under the influence of rock and folk music, composers like Steve Reich, modal jazz pioneered by Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and influences from India, the Middle East and pre-classical Western music. Functional harmony is a development of the kind of harmony used by Bach and Mozart. Jazz up to around 1960 was primarily based on this kind of harmony, and jazz improvisation was concerned with the improvising over songs written by the classically trained songwriters and film composers of the era. These composers all played the piano, so in a sense functional harmony is piano harmony. It’s not really guitar shaped. When I talk about functional harmony I’ll mostly be talking about ways we can improvise and compose on pre-existing jazz standards rather than making up new progressions. -

Riemann's Functional Framework for Extended Jazz Harmony James

Riemann’s Functional Framework for Extended Jazz Harmony James McGowan The I or tonic chord is the only chord which gives the feeling of complete rest or relaxation. Since the I chord acts as the point of rest there is generated in the other chords a feeling of tension or restlessness. The other chords therefore must 1 eventually return to the tonic chord if a feeling of relaxation is desired. Invoking several musical metaphors, Ricigliano’s comment could apply equally well to the tension and release of any tonal music, not only jazz. Indeed, such metaphors serve as essential points of departure for some extended treatises in music theory.2 Andrew Jaffe further associates “tonic,” “stability,” and “consonance,” when he states: “Two terms used to refer to the extremes of harmonic stability and instability within an individual chord or a chord progression are dissonance and consonance.”3 One should acknowledge, however, that to the non-jazz reader, reference to “tonic chord” implicitly means triad. This is not the case for Ricigliano, Jaffe, or numerous other writers of pedagogical jazz theory.4 Rather, in complete indifference to, ignorance of, or reaction against the common-practice principle that only triads or 1 Ricigliano 1967, 21. 2 A prime example, Berry applies the metaphor of “motion” to explore “Formal processes and element-actions of growth and decline” within different musical domains, in diverse stylistic contexts. Berry 1976, 6 (also see 111–2). An important precedent for Berry’s work in the metaphoric dynamism of harmony and other parameters is found in the writings of Kurth – particularly in his conceptions of “sensuous” and “energetic” harmony. -

How to Navigate Chord Changes by Austin Vickrey (Masterclass for Clearwater Jazz Holiday Master Sessions 4/22/21) Overview

How to Navigate Chord Changes By Austin Vickrey (Masterclass for Clearwater Jazz Holiday Master Sessions 4/22/21) Overview • What are chord changes? • Chord basics: Construction, types/qualities • Chords & Scales and how they work together • Learning your chords • Approaches to improvising over chords • Arpeggios, scales, chord tones, guide tones, connecting notes, resolutions • Thinking outside the box: techniques and exercises to enhance and “spice up” your improvisation over chords What are “chord changes?” • The series of musical chords that make up the harmony to support the melody of a song or part of a song (solo section). • The word “changes” refers to the chord “progression,” the original term. In the jazz world, we call them changes because they typically change chord quality from one chord to the next as the song is played. (We will discuss what I mean by “quality” later.) • Most chord progressions in songs tend to repeat the series over and over for improvisors to play solos and melodies. • Chord changes in jazz can be any length. Most tunes we solo over have a form with a certain number of measures (8, 12, 16, 24, 32, etc.). What makes up a chord? • A “chord" is defined as three or more musical pitches (notes) sounding at the same time. • The sonority of a chord depends on how these pitches are specifically arranged or “stacked.” • Consonant chords - chords that sound “pleasing” to the ear • Dissonant chords - chords that do not sound “pleasing” to the ear Basic Common Chord Types • Triad - 3 note chord arranged in thirds • Lowest note - Root, middle note - 3rd, highest note - 5th. -

Theory Placement Examination (D

SAMPLE Placement Exam for Incoming Grads Name: _______________________ (Compiled by David Bashwiner, University of New Mexico, June 2013) WRITTEN EXAM I. Scales Notate the following scales using accidentals but no key signatures. Write the scale in both ascending and descending forms only if they differ. B major F melodic minor C-sharp harmonic minor II. Key Signatures Notate the following key signatures on both staves. E-flat minor F-sharp major Sample Graduate Theory Placement Examination (D. Bashwiner, UNM, 2013) III. Intervals Identify the specific interval between the given pitches (e.g., m2, M2, d5, P5, A5). Interval: ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ Note: the sharp is on the A, not the G. Interval: ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ IV. Rhythm and Meter Write the following rhythmic series first in 3/4 and then in 6/8. You may have to break larger durations into smaller ones connected by ties. Make sure to use beams and ties to clarify the meter (i.e. divide six-eight bars into two, and divide three-four bars into three). 2 Sample Graduate Theory Placement Examination (D. Bashwiner, UNM, 2013) V. Triads and Seventh Chords A. For each of the following sonorities, indicate the root of the chord, its quality, and its figured bass (being sure to include any necessary accidentals in the figures). For quality of chord use the following abbreviations: M=major, m=minor, d=diminished, A=augmented, MM=major-major (major triad with a major seventh), Mm=major-minor, mm=minor-minor, dm=diminished-minor (half-diminished), dd=fully diminished. Root: Quality: Figured Bass: B. -

Shall We Stomp?

Volume 36 • Issue 2 February 2008 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Shall We Stomp? The NJJS proudly presents the 39th Annual Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp ew Jersey’s longest Nrunning traditional jazz party roars into town once again on Sunday, March 2 when the 2008 Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp is pre- sented in the Grand Ballroom of the Birchwood Manor in Whippany, NJ — and you are cordially invited. Slated to take the ballroom stage for five hours of nearly non-stop jazz are the Smith Street Society Jazz Band, trumpeter Jon Erik-Kellso and his band, vocalist Barbara Rosene and group and George Gee’s Jump, Jivin’ Wailers PEABODY AT PEE WEE: Midori Asakura and Chad Fasca hot footing on the dance floor at the 2007 Stomp. Photo by Cheri Rogowsky. Story continued on page 26. 2008 Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp MARCH 2, 2008 Birchwood Manor, Whippany TICKETS NOW AVAILABLE see ad page 3, pages 8, 26, 27 ARTICLES Lorraine Foster/New at IJS . 34 Morris, Ocean . 48 William Paterson University . 19 in this issue: Classic Stine. 9 Zan Stewart’s Top 10. 35 Institute of Jazz Studies/ Lana’s Fine Dining . 21 NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Jazz from Archives. 49 Jazzdagen Tours. 23 Big Band in the Sky . 10 Yours for a Song . 36 Pres Sez/NJJS Calendar Somewhere There’s Music . 50 Community Theatre. 25 & Bulletin Board. 2 Jazz U: College Jazz Scene . 18 REVIEWS The Name Dropper . 51 Watchung Arts Center. 31 Jazzfest at Sea. -

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors Richard Bass Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 38, No. 2. (Autumn, 1994), pp. 155-186. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2909%28199423%2938%3A2%3C155%3AMOOAWI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X Journal of Music Theory is currently published by Yale University Department of Music. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/yudm.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jul 30 09:19:06 2007 MODELS OF OCTATONIC AND WHOLE-TONE INTERACTION: GEORGE CRUMB AND HIS PREDECESSORS Richard Bass A bifurcated view of pitch structure in early twentieth-century music has become more explicit in recent analytic writings. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

Teaching Guide: Area of Study 7

Teaching guide: Area of study 7 – Art music since 1910 This resource is a teaching guide for Area of Study 7 (Art music since 1910) for our A-level Music specification (7272). Teachers and students will find explanations and examples of all the musical elements required for the Listening section of the examination, as well as examples for listening and composing activities and suggestions for further listening to aid responses to the essay questions. Glossary The list below includes terms found in the specification, arranged into musical elements, together with some examples. Melody Modes of limited transposition Messiaen’s melodic and harmonic language is based upon the seven modes of limited transposition. These scales divide the octave into different arrangements of semitones, tones and minor or major thirds which are unlike tonal scales, medieval modes (such as Dorian or Phrygian) or serial tone rows all of which can be transposed twelve times. They are distinctive in that they: • have varying numbers of pitches (Mode 1 contains six, Mode 2 has eight and Mode 7 has ten) • divide the octave in half (the augmented 4th being the point of symmetry - except in Mode 3) • can be transposed a limited number of times (Mode 1 has two, Mode 2 has three) Example: Quartet for the End of Time (movement 2) letter G to H (violin and ‘cello) Mode 3 Whole tone scale A scale where the notes are all one tone apart. Only two such scales exist: Shostakovich uses part of this scale in String Quartet No.8 (fig. 4 in the 1st mvt.) and Messiaen in the 6th movement of Quartet for the End of Time. -

I. the Term Стр. 1 Из 93 Mode 01.10.2013 Mk:@Msitstore:D

Mode Стр. 1 из 93 Mode (from Lat. modus: ‘measure’, ‘standard’; ‘manner’, ‘way’). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; and, most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term ‘mode’ has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and since the 20th century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain phenomena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see Sound, §5(ii). For a discussion of mode in relation to ancient Greek theory see Greece, §I, 6 I. The term II. Medieval modal theory III. Modal theories and polyphonic music IV. Modal scales and traditional music V. Middle East and Asia HAROLD S. POWERS/FRANS WIERING (I–III), JAMES PORTER (IV, 1), HAROLD S. POWERS/JAMES COWDERY (IV, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 1), RUTH DAVIS (V, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 3), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(i)), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (a)–(d)), MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (e)–(i)), ALLAN MARETT, STEPHEN JONES (V, 5(i)), ALLEN MARETT (V, 5(ii), (iii)), HAROLD S. POWERS/ALLAN MARETT (V, 5(iv)) Mode I. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

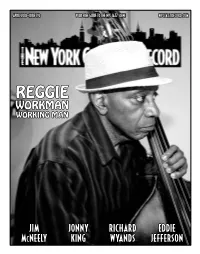

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne