The Modality of Miles Davis and John Coltrane14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Robert GADEN: Slim GAILLARD

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Robert GADEN: Robert Gaden -v,ldr; H.O. McFarlane, Karl Emmerling, Karl Nierenz -tp; Eduard Krause, Paul Hartmann -tb; Kurt Arlt, Joe Alex, Wolf Gradies -ts,as,bs; Hans Becker, Alex Beregowsky, Adalbert Luczkowski -v; Horst Kudritzki -p; Harold M. Kirchstein -g; Karl Grassnick -tu,b; Waldi Luczkowski - d; recorded September 1933 in Berlin 65485 ORIENT EXPRESS 2.47 EOD1717-2 Elec EG2859 Robert Gaden und sein Orchester; recorded September 16, 1933 in Berlin 108044 ORIENTEXPRESS 2.45 OD1717-2 --- Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded December 1936 in Berlin 105298 MEIN ENTZÜCKENDES FRÄULEIN 2.21 ORA 1653-1 HMV EG3821 Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded October 1938 in Berlin 106900 ICH HAB DAS GLÜCK GESEHEN 2.12 ORA3296-2 Elec EG6519 Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded November 1938 in Berlin 106902 SIGNORINA 2.40 ORA3571-2 Elec EG6567 106962 SPANISCHER ZIGEUNERTANZ 2.45 ORA 3370-1 --- Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; Refraingesang: Rudi Schuricke; recorded September 1939 in Berlin 106907 TAUSEND SCHÖNE MÄRCHEN 2.56 ORA4169-1 Elec EG7098 ------------------------------------------ Slim GAILLARD: "Swing Street" Slim Gaillard -g,vib,vo; Slam Stewart -b; Sam Allen -p; Pompey 'Guts' Dobson -d; recorded February 17, 1938 in New York 9079 FLAT FOOT FLOOGIE 2.51 22318-4 Voc 4021 Some sources say that Lionel Hampton plays vibraphone. 98874 CHINATOWN MY CHINATOWN -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

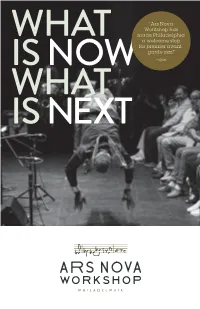

“Ars Nova Workshop Has Made Philadelphia a Welcome Stop For

“Ars Nova Workshop has made Philadelphia a welcome stop WHAT for premier avant- garde jazz." IS NOW —Spin WHAT IS NEXT “Curatorial brilliance” THIS IS —Downbeat OUR Mission AND THIS IS What WE DO Through collaboration and passionate investment, elevates the profile and expands the boundaries of jazz and contemporary music in Philadelphia. We present, on average, 40+ concerts per + year, featuring the biggest names in jazz and Concerts a year contemporary music. Sold Out More than half of our concerts are sold-out shows. We operate through partnerships—with venues, other non-profits, and local and national makers, visionaries, and creatives. We present in spaces throughout Philadelphia with a wide range of capacities, from 100 to 1,300 and more. We are masters at matching the artist with the venue, creating rich context and the appropriate environment for deep listening. OUR CURatoRial and PROGRamminG AMBitions Our logo incorporates a reproduction of a musical line: the iconic title riff from John Coltrane’s manuscript of “A Love Supreme.” While Ars Nova is indebted to this piece and the moment it represents for many reasons, we are especially drawn to the unassuming “ETC.” at the end. Think of everything that “ETC.” can do, promise, and point to: “A Love Supreme” takes off and becomes a new entity, spreading love and possibility and healing and joy and curiosity and discovery and a deeply spiritual present—no longer “just” a phenomenal piece of music that was recorded in a studio one day, but an anthem, a call to a future, a brain- seed in the form of an ear-worm. -

This Is the Official Notice of the Regular Meeting of the Board of Education

This is the official notice of the regular meeting of the Board of Education of the West Irondequoit Central School District, Town of Irondequoit, Monroe County, New York, to be held Thursday evening, October 20, 2016, at 7:00 p.m. in the District Office, 321 List Avenue, Rochester, NY Patricia Kelly School District Clerk October 14, 2016 I. CALL TO ORDER AND PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE II. APPROVAL OF AGENDA III. OATH OF OFFICE FOR STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE IV. ACCEPTANCE OF MINUTES: September 22, 2016, Business Meeting September 29, 2016, Audit Committee October 6, 2016, Study Session V. GOOD NEWS VI. PUBLIC COMMENT VII. SUPERINTENDENT'S REPORT VIII. REPORT OF THE STUDENT REPRESENTATIVES IX. REPORT OF THE TREASURER X. REPORT OF LEADERSHIP STAFF A. Curriculum 1. Art – Incorporating the National Standards B. Personnel 1. Hiring and Retention of Teaching Assistants 2. Resignations/Appointments/Other C. Business 1. Audit Committee 2. Facilities Plan D. Pupil Personnel Services 1. Recommendation of the Committee on Special Education XI. OLD BUSINESS A. Approval of New Course Proposals XII. NEW BUSINESS A. Proposed Field Trip XIII. BOARD REPORTS A. Liaison Reports and Next Scheduled Meeting Date 1. Monroe County School Board Association Legislative Committee (Ann Cunningham, Bill Evans, Carolyn Stahl) Labor Relations (Bill Evans, John Vay) Information Exchange (Brian Charles, John Shafer) 2. School/Community Groups Helmer Nature Center (Meg Steckley, John Vay) PTSA (Ann Cunningham) WIF (Ann Cunningham) WI Alumni Association (Brian Charles) TLC (John Shafer, Carolyn Stahl) Facilities (Bill Evans, John Vay) 3. Schools Irondequoit High School (Meg Steckley) Dake Junior High (John Shafer) Rogers (Ann Cunningham) Iroquois (Brian Charles) Briarwood/Colebrook (Carolyn Stahl) Brookview/Seneca (John Vay) Listwood/Southlawn (Bill Evans) B. -

Nick Grondin Songlist

NICK GRONDIN SONGLIST CLASSICAL Air - Bach Ave Maria - Gounod Cannon in D - Pachabel Gymnopedie - Satie Jesu, Joy Of Man's Desiring - Bach La Rejouissance (From The Royal Fireworks) - Handel Minuet In G - Bach O Mio Babbino Caro - Puccini Ode To Joy - Beethoven Spring (From The Four Seasons) - Vivaldi Trumpet Voluntary - Clarke JAZZ All Blues - Miles Davis Blue In Green - Miles Davis Blue Trane - John Coltrane Do Nothing Til You Hear From Me - Ellington Don't Get Around Much Anymore - Ellington Equinox - John Coltrane Fly Me to the Moon - Sinatra Four - Miles Davis Freddie Freeloader - Miles Davis The Girl From Ipanema - Jobim I Got Rhythm - Gershwin If I Were A Bell - Sinatra In A Sentimental Mood - Ellington Moon River - Sinatra My Favorite Things - Rodgers and Hammerstein My Funny Valentine - Sinatra The Nearness Of You - Sinatra Naima - John Coltrane On The Sunny Side Of The Street - Sinatra Our Love Is Here To Stay - Gershwin Prelude to A Kiss - Ellington Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars - Jobim So What - Miles Davis Sonnymoon For Two - Sonny Rollins St. Thomas - Sonny Rollins Summertime - Gershwin Take The A Train - Ellington You Can't Take That Away From Me - Gershwin Wave - Jobim POPULAR All My Loving - Beatles All You Need Is Love - Beatles Beautiful Day - U2 Blackbird - Beatles Here Comes The Sun - Beatles Hey Jude - Beatles And I Love Her - Beatles I'm Yours - Jason Mraz In My Life - Beatles I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For - U2 I Will - Beatles Let It Be - Beatles Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da - Beatles Somewhere Over The Rainbow - Iz Stand By Me - Ben E. -

Chico Hamilton Peregrinations Mp3, Flac, Wma

Chico Hamilton Peregrinations mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Peregrinations Country: Germany Released: 1975 Style: Jazz-Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1195 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1404 mb WMA version RAR size: 1571 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 481 Other Formats: DMF MMF AC3 MOD MP2 AA AUD Tracklist Hide Credits V-O A1 3:58 Soloist – Arthur Blythe, Barry FinnertyWritten-By – Steve Turre The Morning Side Of Love A2 5:18 Soloist – Barry Finnerty, Joe BeckWritten-By – Chico Hamilton Abdullah And Abraham A3 4:16 Written-By, Soloist – Arnie Lawrence Andy's Walk A4 4:15 Written-By – Chico Hamilton Peregrinations A5 3:16 Written-By – Chico Hamilton Sweet Dreams B1 5:53 Soloist – Arthur Blythe, Barry FinnertyWritten-By – Chico Hamilton Little Lisa B2 2:49 Written-By – Steve Turre Space For Stacy B3 3:06 Written-By – Chico Hamilton On And Off B4 2:56 Written-By – Chico Hamilton It's About That Time B5 0:57 Written-By – Chico Hamilton Companies, etc. Recorded At – A&R Studios Recorded At – Sound Factory West Mixed At – Westlake Audio Mastered At – Kendun Recorders Credits Art Direction, Design – Bob Cato Bass – Steve Turre Congas, Bongos, Percussion – Abdullah Drums, Percussion – Chico Hamilton Effects [Other Special Effects By] – Jerrell Ballard Engineer – Don Hahn, Steve Maslow Executive-Producer – George Butler Guitar – Barry Finnerty, Joe Beck Horns – Arnie Lawrence, Arthur Blythe, Steve Turre Keyboards – Jerry Peters Liner Notes – Stanley Crouch Mixed By, Mastered By – Baker Bigsby Producer, Effects [Other Special Effects By] – Keg Johnson Synthesizer [Programming] – Charlotte Politte Vocals – Julia Tillman*, Luther Waters, Maxine Willard*, Oren Waters Notes Rhythm tracks recorded at A&R Recording Studios, New York, NY. -

Second Wind: a Tribute to E Music of Bill Evans

Chuck Israels Jazz Orchestra contribution to Evans’ body of work. Second Wind: A Tribute To e Music Israels, of course, was the replacement for the Of Bill Evans legendary Scott LaFaro, who died in a car accident SOULPATCH in 1961, the loss of a friend and creative partner ++++ ½ that had devastated Evans. Eventually he found his footing with Israels, who had worked with As the famous album title has it, everybody digs Bill Evans. a who’s who of greats including Billie Holiday, But not everybody has su#ciently dug Chuck Israels, Evans’ Benny Goodman, Coleman Hawkins and John great, underappreciated bassist from his second trio (1962– Coltrane. Besides being a brilliant technician with 1966). is album, Israels’ return to full-time performing a wonderful round tone, Israels was an exquisitely aer a 30-year teaching career, should win him new fans for sensitive musical partner who helped bring out the his prodigious skills as both arranger and bassist, even as it best in the introspective Evans. Aer his stint with serves to remind longtime Evans devotees of his signi!cant Evans, Israels studied composition and arrang- ing with Hall Overton, who arranged elonious Monk compositions for a tentet at Monk’s tri- umphant 1959 Town Hall concert. Later, Israels became a pioneer of the jazz repertory movement, founding and leading the National Jazz Ensemble from 1973 to 1981. Although Israels has played Evans tunes with others (notably Danish pianist omas Clausen on the excellent 2003 trio album For Bill ), this is the !rst time he has orchestrated a whole album of songs associated with or inspired by Evans for a larger ensemble.