Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

Booker Little

1 The TRUMPET of BOOKER LITTLE Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Feb. 11, 2020 2 Born: Memphis, April 2, 1938 Died: NYC. Oct. 5, 1961 Introduction: You may not believe this, but the vintage Oslo Jazz Circle, firmly founded on the swinging thirties, was very interested in the modern trends represented by Eric Dolphy and through him, was introduced to the magnificent trumpet playing by the young Booker Little. Even those sceptical in the beginning gave in and agreed that here was something very special. History: Born into a musical family and played clarinet for a few months before taking up the trumpet at the age of 12; he took part in jam sessions with Phineas Newborn while still in his teens. Graduated from Manassas High School. While attending the Chicago Conservatory (1956-58) he played with Johnny Griffin and Walter Perkins’s group MJT+3; he then played with Max Roach (June 1958 to February 1959), worked as a freelancer in New York with, among others, Mal Waldron, and from February 1960 worked again with Roach. With Eric Dolphy he took part in the recording of John Coltrane’s album “Africa Brass” (1961) and led a quintet at the Five Spot in New York in July 1961. Booker Little’s playing was characterized by an open, gentle tone, a breathy attack on individual notes, a nd a subtle vibrato. His soli had the brisk tempi, wide range, and clean lines of hard bop, but he also enlarged his musical vocabulary by making sophisticated use of dissonance, which, especially in his collaborations with Dolphy, brought his playing close to free jazz. -

Victory and Sorrow: the Music & Life of Booker Little

ii VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSIC & LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE by DYLAN LAGAMMA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History & Research written under the direction of Henry Martin and approved by _________________________ _________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2017 i ©2017 Dylan LaGamma ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSICAL LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE BY DYLAN LAGAMMA Dissertation Director: Henry Martin Booker Little, a masterful trumpeter and composer, passed away in 1961 at the age of twenty-three. Little's untimely death, and still yet extensive recording career,1 presents yet another example of early passing among innovative and influential trumpeters. Like Clifford Brown before him, Theodore “Fats” Navarro before him, Little's death left a gap the in jazz world as both a sophisticated technician and an inspiring composer. However, unlike his predecessors Little is hardly – if ever – mentioned in jazz texts and classrooms. His influence is all but non-existent except to those who have researched his work. More than likely he is the victim of too early a death: Brown passed away at twenty-five and Navarro, twenty-six. Bob Cranshaw, who is present on Little's first recording,2 remarks, “Nobody got a chance to really experience [him]...very few remember him because nobody got a chance to really hear him or see him.”3 Given this, and his later work with more avant-garde and dissonant harmonic/melodic structure as a writing partner with Eric Dolphy, it is no wonder that his remembered career has followed more the path of James P. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Brandon Patrick George, Flute Toyin Spellman-Diaz, Oboe Mark Dover, Clarinet Jeff Scott, French Horn Monica Ellis, Bassoon

Brandon Patrick George, Flute Toyin Spellman-Diaz, Oboe Mark Dover, Clarinet Jeff Scott, French Horn Monica Ellis, Bassoon Program Startin’ Sumthin’ Jeff Scott Quintet for Winds John Harbison iv. Scherzo v. Finale Kites Over Havana Paquito D’Rivera arr. Valerie Coleman Pavane Gabriel Fauré arr. Jeff Scott Dance Mediterranea Simon Shaheen arr. Jeff Scott Opening Act Assistant Professor of Music Matthew Evan Taylor If not NOW, then WHEN! Matthew Evan Taylor Alto Improvisation 3, Contrasts Program Notes Jeff Scott Startin’ Sumthin’ Startin’ Sumthin’ is a modern take on the genre of Ragtime music. With an emphasis on ragged! The defining characteristic of Ragtime music is a specific type of syncopation in which melodic accents occur between metrical beats. This results in a melody that seems to be avoiding some metrical beats of the accompaniment by emphasizing notes that either anticipate or follow the beat. The ultimate (and intended) effect on the listener is actually to accentuate the beat, thereby inducing the listener to move to the music. Scott Joplin, the composer/pianist known as the “King of Ragtime,” called the effect “weird and intoxicating.” ―Note by Jeff Scott John Harbison Quintet for Winds John Harbison studied with Walter Piston at Harvard, with Boris Blacher in Berlin, and with Roger Sessions and Earl Kim at Princeton; in 1969 he joined the faculty at MIT. His compositions include two operas (one on Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale), orchestral works, concertos for piano, violin, and brass quintet, chamber music, and vocal settings on an impressive range of texts. Harbison has also made a career as a conductor; he has been conductor of the Boston Cantata Singers and has guest conducted the San Francisco and Boston Symphony Orchestras. -

Roberto Miranda Dewey Johnson

ENCORE played all those instruments and he taught those taught me.” instruments to me and my brother. One of the Miranda recalls that he made his first recording at ROBERTO favorite memories I have of my life is watching my age 21 with pianist Larry Nash and drummer Woody parents dance to Latin music. Man! That still is an “Sonship” Theus, who were both just 16 at the time. incredible memory.” The name of the album was The Beginning and it also Years later in school, his brother played percussion featured saxophonists Herman Riley and Pony MIRANDA in concert band and Miranda asked for a trumpet. All Poindexter and trumpeter Luis Gasca (who, under those chairs were taken, he was told, so he requested contract elsewhere, used a pseudonym). The drummer by anders griffen a guitar, but was told that was not a band instrument. became a dear friend and was instrumental in Miranda They did need bass players, however, so that’s when he ending up on a record with Charles Lloyd (Waves, Bassist Roberto Miranda has been on many musical first played bass but gave it up after the semester. The A&M, 1972), even though, as it was happening, adventures, performing and recording with his brothers had formed a band together in which Louis Miranda didn’t even know he was being recorded. mentors—Horace Tapscott, John Carter and Bobby played drum set and Roberto played congas. As “Sonship Theus was a very close friend of mine. Bradford and later, Kenny Burrell—as well as artists teenagers they started a social club and held dances. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

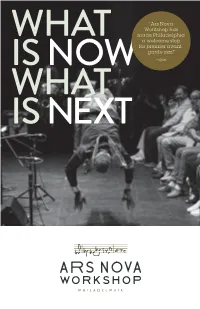

“Ars Nova Workshop Has Made Philadelphia a Welcome Stop For

“Ars Nova Workshop has made Philadelphia a welcome stop WHAT for premier avant- garde jazz." IS NOW —Spin WHAT IS NEXT “Curatorial brilliance” THIS IS —Downbeat OUR Mission AND THIS IS What WE DO Through collaboration and passionate investment, elevates the profile and expands the boundaries of jazz and contemporary music in Philadelphia. We present, on average, 40+ concerts per + year, featuring the biggest names in jazz and Concerts a year contemporary music. Sold Out More than half of our concerts are sold-out shows. We operate through partnerships—with venues, other non-profits, and local and national makers, visionaries, and creatives. We present in spaces throughout Philadelphia with a wide range of capacities, from 100 to 1,300 and more. We are masters at matching the artist with the venue, creating rich context and the appropriate environment for deep listening. OUR CURatoRial and PROGRamminG AMBitions Our logo incorporates a reproduction of a musical line: the iconic title riff from John Coltrane’s manuscript of “A Love Supreme.” While Ars Nova is indebted to this piece and the moment it represents for many reasons, we are especially drawn to the unassuming “ETC.” at the end. Think of everything that “ETC.” can do, promise, and point to: “A Love Supreme” takes off and becomes a new entity, spreading love and possibility and healing and joy and curiosity and discovery and a deeply spiritual present—no longer “just” a phenomenal piece of music that was recorded in a studio one day, but an anthem, a call to a future, a brain- seed in the form of an ear-worm. -

Birth of the Film by Bruce Spiegel

Bill Evans Time Remembered Birth of the Film by Bruce Spiegel There was a crystal moment when you knew for certain this Bill Evans movie was going to happen. And it was all due to drummer Paul Motian. But let me digress for a moment. I have been listening to jazz since I was a kid, not knowing why but just listening. My father had a webcor portable record player and he had a small but mighty collection of brand new 33 rpm albums. There was Benny Goodman in hi fi, there was the Uptown Stars play Duke Ellington. Illinois Jacquet and Slam Stewart; then there was Fats Waller, and with Honeysuckle Rose and the flip side of the 45, Your Feet’s Too Big. How I loved that song. “Up in Harlem there was 4 of us, me your two big feet, and you!” At college level or maybe it was high school, it was Art Blakey and the Jazz messengers, moaning Horace silver, everything of his, and then the cavalcade began with Monk, Trane, and Miles. I bought an old fisher- amp, speaker and record player and got everything possible, all the way from Louis Armstrong to Jelly Roll Morton; from Teddy Wilson to Sonny Clark. For me it was a young thirst for the best in jazz, just a lifetime of searching for the best records, the real records. And making a collection of them. It was a life-long journey. I had heard Bill Evans but it wasn’t until I was older, much older that I was smitten; really hit hard with his music. -

The Modality of Miles Davis and John Coltrane14

CURRENT A HEAD ■ 371 MILES DAVIS so what JOHN COLTRANE giant steps JOHN COLTRANE acknowledgement MILES DAVIS e.s.p. THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE14 ■ THE SORCERER: MILES DAVIS (1926–1991) We have encountered Miles Davis in earlier chapters, and will again in later ones. No one looms larger in the postwar era, in part because no one had a greater capacity for change. Davis was no chameleon, adapting himself to the latest trends. His innovations, signaling what he called “new directions,” changed the ground rules of jazz at least fi ve times in the years of his greatest impact, 1949–69. ■ In 1949–50, Davis’s “birth of the cool” sessions (see Chapter 12) helped to focus the attentions of a young generation of musicians looking beyond bebop, and launched the cool jazz movement. ■ In 1954, his recording of “Walkin’” acted as an antidote to cool jazz’s increasing deli- cacy and reliance on classical music, and provided an impetus for the development of hard bop. ■ From 1957 to 1960, Davis’s three major collaborations with Gil Evans enlarged the scope of jazz composition, big-band music, and recording projects, projecting a deep, meditative mood that was new in jazz. At twenty-three, Miles Davis had served a rigorous apprenticeship with Charlie Parker and was now (1949) about to launch the cool jazz © HERMAN LEONARD PHOTOGRAPHY LLC/CTS IMAGES.COM movement with his nonet. wwnorton.com/studyspace 371 7455_e14_p370-401.indd 371 11/24/08 3:35:58 PM 372 ■ CHAPTER 14 THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE ■ In 1959, Kind of Blue, the culmination of Davis’s experiments with modal improvisation, transformed jazz performance, replacing bebop’s harmonic complexity with a style that favored melody and nuance. -

The African American Historic Designation Council (Aahdc)

A COMPILTION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS AND HISTORIC SITES IN THE TOWN OF HUNTINGTON Presented by THE AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC DESIGNATION COUNCIL (AAHDC) John William Coltrane On Candlewood Path in Dix Hills, New York. obscured among overgrown trees, sits the home of jazz legend John Coltrane, a worldwide jazz icon. Born on September 23, 1920, in Hamlet, North Carolina, Coltrane followed in the foot steps of his father who played several instruments. He learned music at an early age, influenced by Lester Young and Johnny Hodges and others which led him to shi to the alto saxophone. He connued his musical training in Philadelphia and was called to military service during World War II, where he performed in the U.S. Navy Band. Aer the war, Coltrane connued his zest for music, playing the tenor saxophone with the Eddie Vinson Band, performing with Jimmy Heath. He later joined the Dizzy Gillespie Band. His passion for experimentaon was be- ginning to take shape; however, it was his work with the Miles Davis Quintet in 1958 that would lead to his own musical evoluon. He was impressed with the freedom given to him by Miles Davis' music and was quoted as say- ing "Miles' music gave me plenty of freedom." This freedom led him to form his own band. By 1960, Coltrane had formed his own quartet, which included pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones, and bassist Jimmy Garrison. He eventually added other players including Eric Dolphy and Pharaoh Sanders. The John Coltrane Quartet, a novelty group, created some of the most innovave and expressive music in jazz histo- ry, including hit albums: "My Favorite Things," "Africa Brass," "Impressions," and his most famous piece, "A Love Supreme." "A Love Supreme," composed in his home on Candlewood Path, not only effected posive change in North America, but helped to change people's percepon of African Americans throughout the world.