The Tiberian Pronunciation Tradition of Biblical Hebrew, Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alif and Hamza Alif) Is One of the Simplest Letters of the Alphabet

’alif and hamza alif) is one of the simplest letters of the alphabet. Its isolated form is simply a vertical’) ﺍ stroke, written from top to bottom. In its final position it is written as the same vertical stroke, but joined at the base to the preceding letter. Because of this connecting line – and this is very important – it is written from bottom to top instead of top to bottom. Practise these to get the feel of the direction of the stroke. The letter 'alif is one of a number of non-connecting letters. This means that it is never connected to the letter that comes after it. Non-connecting letters therefore have no initial or medial forms. They can appear in only two ways: isolated or final, meaning connected to the preceding letter. Reminder about pronunciation The letter 'alif represents the long vowel aa. Usually this vowel sounds like a lengthened version of the a in pat. In some positions, however (we will explain this later), it sounds more like the a in father. One of the most important functions of 'alif is not as an independent sound but as the You can look back at what we said about .(ﺀ) carrier, or a ‘bearer’, of another letter: hamza hamza. Later we will discuss hamza in more detail. Here we will go through one of the most common uses of hamza: its combination with 'alif at the beginning or a word. One of the rules of the Arabic language is that no word can begin with a vowel. Many Arabic words may sound to the beginner as though they start with a vowel, but in fact they begin with a glottal stop: that little catch in the voice that is represented by hamza. -

The Hebrew Alphabet

BBH2 Textbook Supplement Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1 The following comments explain, provide mnemonics for, answer questions that students have raised about, and otherwise supplement the second edition of Basics of Biblical Hebrew by Pratico and Van Pelt. Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1.1 The consonants For begadkephat letters (§1.5), the pronunciation in §1.1 is the pronunciation with the Dagesh Lene (§1.5), even though the Dagesh Lene is not shown in §1.1. .Kaf” has an “off” sound“ כ The name It looks like open mouth coughing or a cup of coffee on its side. .Qof” is pronounced with either an “oh” sound or an “oo” sound“ ק The name It has a circle (like the letter “o” inside it). Also, it is transliterated with the letter q, and it looks like a backwards q. here are different wa s of spellin the na es of letters. lef leph leˉ There are many different ways to write the consonants. See below (page 3) for a table of examples. See my chapter 1 overheads for suggested letter shapes, stroke order, and the keys to distinguishing similar-looking letters. ”.having its dot on the left: “Sin is never ri ht ׂש Mnemonic for Sin ׁש and Shin ׂש Order of Sin ׁש before Shin ׂש Our textbook and Biblical Hebrew lexicons put Sin Some alphabet songs on YouTube reverse the order of Sin and Shin. Modern Hebrew dictionaries, the acrostic poems in the Bible, and ancient abecedaries (inscriptions in which someone wrote the alphabet) all treat Sin and Shin as the same letter. -

The Tiberian Pronunciation Tradition of Biblical Hebrew, Volume 2

Cambridge Semitic Languages and Cultures The Tiberian Pronunciation Khan Tradition of Biblical Hebrew (Vol. II) The Tiberian Pronunciation Geoffrey Khan Tradition of Biblical Hebrew The form of Biblical Hebrew that is presented in printed edi� ons, with vocaliza� on and accent signs, has its origin in medieval manuscripts of the Bible. The vocaliza� on and Tradition of Biblical Hebrew Vol. II Volume II accent signs are nota� on systems that were created in Tiberias in the early Islamic period by scholars known as the Tiberian Masoretes, but the oral tradi� on they represent has roots in an� quity. The gramma� cal textbooks and reference grammars of Biblical Hebrew The Tiberian Pronunciation in use today are heirs to centuries of tradi� on of gramma� cal works on Biblical Hebrew in GEOFFREY KHAN Europe. The paradox is that this European tradi� on of Biblical Hebrew grammar did not have direct access to the way the Tiberian Masoretes were pronouncing Biblical Hebrew. In the last few decades, research of manuscript sources from the medieval Middle East has made it possible to reconstruct with considerable accuracy the pronuncia� on of the Tiberian Masoretes, which has come to be known as the ‘Tiberian pronuncia� on tradi� on’. This book presents the current state of knowledge of the Tiberian pronuncia� on tradi� on of Biblical Hebrew and a full edi� on of one of the key medieval sources, Hidāyat al-Qāriʾ ‘The Guide for the Reader’, by ʾAbū al-Faraj Hārūn. It is hoped that the book will help to break the mould of current gramma� cal descrip� ons of Biblical Hebrew and form a bridge between modern tradi� ons of grammar and the school of the Masoretes of Tiberias. -

Fragmente Jüdischer Kultur in Der Stadtbibliothek Mainz

Veröffentlichungen der Bibliotheken der Stadt Mainz Herausgegeben von der Landeshauptstadt Mainz Band 62 Andreas Lehnardt und Annelen Ottermann Fragmente jüdischer Kultur in der Stadtbibliothek Mainz Entdeckungen und Deutungen Mainz 2014 Umschlag: III d:4°/394 ® Gestaltung: Tanja Labs (artefont) Bibliografi sche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografi e; detaillierte bibliografi sche Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-00-046570-3 © Landeshauptstadt Mainz / Bibliotheken der Stadt Mainz 2014 Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung der Bibliotheken der Stadt Mainz unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen jeder Art, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfi lmungen und für die Einspeicherung in elektronische Systeme. Gestaltung, Satz, Einband: Silja Geisler, Tanja Labs (artefont) und Elke Morlok Druck: Lindner OHG Mainz Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort des Direktors 7 Vorwort 9 Allgemeine Hinweise 11 1. Einführung 13 Hebräische Makulaturforschung in Mainz 15 Die Stadtbibliothek Mainz und ihre Bestände 18 Zwischen Verfolgung und Vernachlässigung - Wie kamen die Fragmente zu den Büchern? 19 Was besagen die Fragmente über die jüdische Lesekultur im Mittelalter? Welche Schriften wurden von Juden gelesen? 27 Zur Beschreibung der Fragmente 30 2. Tora-Rollen 35 3. Bibel (Tanakh), Masora und Targum 49 4. Bibel-Kommentar 87 5. Mischna 95 6. Talmud 105 7. Talmud-Kommentare 131 8. Midrasch Tanchuma 145 9. Machsor 157 10. Piyyut-Kommentar 201 11. Kodizes 207 12. Nicht identifi zierte hebräische Fragmente 223 13. Anhang: Orientalische Genisa-Fragmente 233 14. Liste aller hebräischen Fragmente in der Stadtbibliothek Mainz 241 15. -

On the Proper Pronunciation of Hebrew

On the proper pronunciation of Hebrew Every language has its own mixture of phonological, morphological, and syntactic features that, taken together, constitute its unique character and identity. For the most part, these features are of interest only to a small minority of professionals and geeks; the better part of mankind remains obliviously content, interested only in how to practically manipulate the language so as to generate and absorb meaning. This is as true of Hebrew as it is of any other language. There is, however, one feature of Hebrew that protrudes so obnoxiously that it cannot escape the attention of the most minimally thoughtful person, whether he be a native speaker or a foreign student. On the one hand, Hebrew has one of the most phonetically regular alphabets of any language, a fact that is particularly remarkable since this alphabet has remained unchanged for at least 2,100 years. There are scarcely any Hebrew words that cannot be deciphered with complete accuracy, providing, of course, that the nikud is added. On the other hand ,this phonetically regular alphabet has an abundance of completely redundant letters whose sole purpose seems to be to confuse people trying to spell. So far, we have said nothing remotely controversial. Everyone, from the native speaker to the ulpan student, religious and secular, will freely comment on this odd feature of Hebrew and its ability to generate all sorts of amusement and confusion. However, this friendly atmosphere is instantly shattered the second anyone suggests a blindingly obvious thesis, namely that this feature of Hebrew is not a feature at all, but a mistake. -

Word Stress and Vowel Neutralization in Modern Standard Arabic

Word Stress and Vowel Neutralization in Modern Standard Arabic Jack Halpern (春遍雀來) The CJK Dictionary Institute (日中韓辭典研究所) 34-14, 2-chome, Tohoku, Niiza-shi, Saitama 352-0001, Japan [email protected] rules differ somewhat from those used in liturgi- Abstract cal Arabic. Word stress in Modern Standard Arabic is of Arabic word stress and vowel neutralization great importance to language learners, while rules have been the object of various studies, precise stress rules can help enhance Arabic such as Janssens (1972), Mitchell (1990) and speech technology applications. Though Ara- Ryding (2005). Though some grammar books bic word stress and vowel neutralization rules offer stress rules that appear short and simple, have been the object of various studies, the lit- erature is sometimes inaccurate or contradic- upon careful examination they turn out to be in- tory. Most Arabic grammar books give stress complete, ambiguous or inaccurate. Moreover, rules that are inadequate or incomplete, while the linguistic literature often contains inaccura- vowel neutralization is hardly mentioned. The cies, partially because little or no distinction is aim of this paper is to present stress and neu- made between MSA and liturgical Arabic, or tralization rules that are both linguistically ac- because the rules are based on Egyptian-accented curate and pedagogically useful based on how MSA (Mitchell, 1990), which differs from stan- spoken MSA is actually pronounced. dard MSA in important ways. 1 Introduction Arabic stress and neutralization rules are wor- Word stress in both Modern Standard Arabic thy of serious investigation. Other than being of (MSA) and the dialects is non-phonemic. -

Encoded Representations for Distinct Positional Uses of Hebrew Meteg Peter Constable, Microsoft Corporation 2004-09-13

Encoded representations for distinct positional uses of Hebrew Meteg Peter Constable, Microsoft Corporation 2004-09-13 In some uses of the Hebrew script, particularly for Biblical text, a variety of combining marks are used. One of these marks is meteg, encoded as U+05BD, HEBREW POINT METEG. Meteg frequently occurs together with other combining marks. When meteg co-occurs with another mark that occupies the same general space below the base character, different relative arrangements of meteg and these other marks are possible. In some uses it is considered necessary to specify these relative arrangements of meteg and other marks in the encoded representation. A proposal1 has been submitted to UTC for how these different positionings of meteg should be specified in encoded representations. This proposal makes use of the control characters COMBINING GRAPHEME JOINER (CGJ), ZERO WIDTH JOINER (ZWJ) and ZERO WIDTH NON-JOINER (ZWNJ). This public-review issue is soliciting feedback on this proposal and, in particular, on the proposed use of ZWJ and ZWNJ for distinguishing between the different positional uses of the meteg. The details in this case are somewhat complex. Familiarity with combining marks, canonical combining classes, canonical ordering and canonical equivalence is assumed. Some background information on those topics is provided in an appendix. 1. Background: meteg in combination with below-base vowel marks Biblical Hebrew text includes a number of marks used to annotate the text, which were introduced by Masoretic scholars over a thousand years ago. These marks include vowel points and a number of accentuation marks that indicate structural units of the text, serving to guide the reader or chanter. -

![Adaptations of Hebrew Script -Mala Enciklopedija Prosvetq I978 [Small Prosveta Encyclopedia]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2327/adaptations-of-hebrew-script-mala-enciklopedija-prosvetq-i978-small-prosveta-encyclopedia-702327.webp)

Adaptations of Hebrew Script -Mala Enciklopedija Prosvetq I978 [Small Prosveta Encyclopedia]

726 PART X: USE AND ADAPTATION OF SCRIPTS Series Minor 8) The Hague: Mouton SECTION 6I Ly&in, V. I t952. Drevnepermskij jazyk [The Old Pemic language] Moscow: Izdalel'slvo Aka- demii Nauk SSSR ry6r. Komi-russkij sLovar' [Komi-Russian diclionary] Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe Izda- tel'slvo Inostrannyx i Nacional'nyx Slovuej. Adaptations of Hebrew Script -MaLa Enciklopedija Prosvetq I978 [Small Prosveta encycloPedia]. Belgrade. Moll, T. A,, & P. I InEnlikdj t951. Cukotsko-russkij sLovaf [Chukchee-Russian dicrionary] Len- BENJAMIN HARY ingrad: Gosudtrstvemoe udebno-pedagogideskoe izdatel'stvo Ministerstva Prosveldenija RSFSR Poppe, Nicholas. 1963 Tatqr Manual (Indima Universily Publications, Uralic atrd Altaic Series 25) Mouton Bloomington: Indiana University; The Hague: "lagguages" rgjo. Mongolian lnnguage Handbook.Washington, D C.: Center for Applied Linguistics Jewish or ethnolects HerbertH Papet(Intema- Rastorgueva,V.S. 1963.A ShortSketchofTajikGrammar, fans anded It is probably impossible to offer a purely linguistic definition of a Jewish "language," tional Joumal ofAmerican Linguisticr 29, no part 2) Bloominglon: Indiana University; The - 4, as it is difficult to find many cornmon linguistic criteria that can apply to Judeo- Hague: Moulon. (Russiu orig 'Kratkij oderk grammatiki lad;ikskogo jzyka," in M. V. Rax- Arabic, Judeo-Spanish, and Yiddish, for example. Consequently, a sociolinguistic imi & L V Uspenskaja, eds,Tadiikskurusstj slovar' lTajik-Russian dictionary], Moscow: Gosudustvennoe Izdatel'stvo Inostrmyx i Nacional'tryx SIovarej, r954 ) definition with a more suitable term, such as ethnolect, is in order. An ethnolect is an Sjoberg, Andr€e P. t963. Uzbek StructuraL Grammar (Indiana University Publications, Uralic and independent linguistic entity with its own history and development that refers to a lan- Altaic Series r8). -

How Was the Dageš in Biblical Hebrew Pronounced and Why Is It There? Geoffrey Khan

1 pronounced and why is it בָּתִּ ים How was the dageš in Biblical Hebrew there? Geoffrey Khan houses’ is generally presented as an enigma in‘ בָּתִּ ים The dageš in the Biblical Hebrew plural form descriptions of the language. A wide variety of opinions about it have been expressed in Biblical Hebrew textbooks, reference grammars and the scholarly literature, but many of these are speculative without any direct or comparative evidence. One of the aims of this article is to examine the evidence for the way the dageš was pronounced in this word in sources that give us direct access to the Tiberian Masoretic reading tradition. A second aim is to propose a reason why the word has a dageš on the basis of comparative evidence within Biblical Hebrew reading traditions and other Semitic languages. בָּתִּיםבָּתִּ ים The Pronunciation of the Dageš in .1.0 The Tiberian vocalization signs and accents were created by the Masoretes of Tiberias in the early Islamic period to record an oral tradition of reading. There is evidence that this reading tradition had its roots in the Second Temple period, although some features of it appear to have developed at later periods. 1 The Tiberian reading was regarded in the Middle Ages as the most prestigious and authoritative tradition. On account of the authoritative status of the reading, great efforts were made by the Tiberian Masoretes to fix the tradition in a standardized form. There remained, nevertheless, some degree of variation in reading and sign notation in the Tiberian Masoretic school. By the end of the Masoretic period in the 10 th century C.E. -

Psalms 119 & the Hebrew Aleph

Psalms 119 & the Hebrew Aleph Bet - Part 17 The seventeenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet is called “Pey” (sounds like “pay”). It has the sound of “p” as in “park”. Pey has the numeric value of 80. In modern Hebrew, the letter Pey can appear in three forms: Writing the Letter: Pey Note: Most people draw the Pey in two strokes, as shown. The dot, or “dagesh” mark means the pey makes the “p” sound, as in “park”. Note: The sole difference between the letter Pey and the letter Fey is the presence or absence of the dot in the middle of the letter (called a dagesh mark). When you see the dot in the middle of this letter, pronounce it as a "p"; otherwise, pronounce it as "ph" (or “f”). Five Hebrew letters are formed differently when they appear as the last letter of a word (these forms are sometimes called "sofit" (pronounced "so-feet") forms). Fortunately, the five letters sound the same as their non-sofit cousins, so you do not have to learn any new sounds (or transliterations). The Pey (pronounced “Fey” sofit has a descending tail, as shown on the left. Pey: The Mouth, or Word The pictograph for Pey looks something like a mouth, whereas the classical Hebrew script (Ketav Ashurit) is constructed of a Kaf with an ascending Yod: Notice the “hidden Bet” within the letter Pey. This shape of the letter is required when a Torah scribe writes Torah scrolls, or mezzuzahs. From the Canaanite pictograph, the letter morphed into the Phoenician ketav Ivri, to the Greek letter (Pi), which became the Latin letter “P.” means “mouth” and by extension, “word,” “expression,” “vocalization,” and “speech”. -

The Syntactic Basis of Masoretic Hebrew Punctuation Author(S): Mark Aronoff Source: Language, Vol

Linguistic Society of America Orthography and Linguistic Theory: The Syntactic Basis of Masoretic Hebrew Punctuation Author(s): Mark Aronoff Source: Language, Vol. 61, No. 1 (Mar., 1985), pp. 28-72 Published by: Linguistic Society of America Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/413420 Accessed: 07-02-2019 19:33 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Linguistic Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Language This content downloaded from 129.49.5.35 on Thu, 07 Feb 2019 19:33:17 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms ORTHOGRAPHY AND LINGUISTIC THEORY: THE SYNTACTIC BASIS OF MASORETIC HEBREW PUNCTUATION MARK ARONOFF SUNY Stony Brook The punctuation (accent) system of the Masoretic Hebrew Bible contains a complete unlabeled binary phrase-structure analysis of every verse, based on a single parsing principle. The systems of punctuation, phrase structure, and parsing are each presented here in detail and contrasted with their counterparts in modern linguistics. The entire system is considered as the product of linguistic analysis, rather than as a linguistic system per se; and implications are drawn for the study of written language and writing systems.* To modern linguistics, discussion of written language has been taboo. -

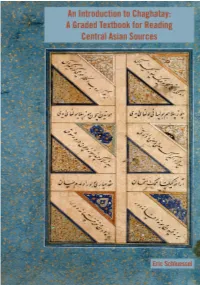

Mpub10110094.Pdf

An Introduction to Chaghatay: A Graded Textbook for Reading Central Asian Sources Eric Schluessel Copyright © 2018 by Eric Schluessel Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. Published in the United States of America by Michigan Publishing Manufactured in the United States of America DOI: 10.3998/mpub.10110094 ISBN 978-1-60785-495-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60785-496-8 (e-book) An imprint of Michigan Publishing, Maize Books serves the publishing needs of the University of Michigan community by making high-quality scholarship widely available in print and online. It represents a new model for authors seeking to share their work within and beyond the academy, offering streamlined selection, production, and distribution processes. Maize Books is intended as a complement to more formal modes of publication in a wide range of disciplinary areas. http://www.maizebooks.org Cover Illustration: "Islamic Calligraphy in the Nasta`liq style." (Credit: Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/chengwfg/, licensed under CC BY 4.0) Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction vi How to Read the Alphabet xi 1 Basic Word Order and Copular Sentences 1 2 Existence 6 3 Plural, Palatal Harmony, and Case Endings 12 4 People and Questions 20 5 The Present-Future Tense 27 6 Possessive