Word Stress and Vowel Neutralization in Modern Standard Arabic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lost Women of Iraq: Family-Based Violence During Armed Conflict © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International November 2015

CEASEFIRE centre for civilian rights Miriam Puttick The Lost Women of Iraq: Family-based violence during armed conflict © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International November 2015 Cover photo: This report has been produced as part of the Ceasefire project, a multi-year pro- Kurdish women and men protesting gramme supported by the European Union to implement a system of civilian-led against violence against women march in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, monitoring of human rights abuses in Iraq, focusing in particular on the rights of November 2008. vulnerable civilians including vulnerable women, internally-displaced persons (IDPs), stateless persons, and ethnic or religious minorities, and to assess the feasibility of © Shwan Mohammed/AFP/Getty Images extending civilian-led monitoring to other country situations. This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the publishers and can un- der no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is a new initiative to develop ‘civilian-led monitoring’ of violations of international humanitarian law or human rights, to pursue legal and political accountability for those responsible for such violations, and to develop the practice of civilian rights. The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is registered as a charity and a company limited by guarantee under English law; charity no: 1160083, company no: 9069133. Minority Rights Group International MRG is an NGO working to secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and understanding between communities. -

Alif and Hamza Alif) Is One of the Simplest Letters of the Alphabet

’alif and hamza alif) is one of the simplest letters of the alphabet. Its isolated form is simply a vertical’) ﺍ stroke, written from top to bottom. In its final position it is written as the same vertical stroke, but joined at the base to the preceding letter. Because of this connecting line – and this is very important – it is written from bottom to top instead of top to bottom. Practise these to get the feel of the direction of the stroke. The letter 'alif is one of a number of non-connecting letters. This means that it is never connected to the letter that comes after it. Non-connecting letters therefore have no initial or medial forms. They can appear in only two ways: isolated or final, meaning connected to the preceding letter. Reminder about pronunciation The letter 'alif represents the long vowel aa. Usually this vowel sounds like a lengthened version of the a in pat. In some positions, however (we will explain this later), it sounds more like the a in father. One of the most important functions of 'alif is not as an independent sound but as the You can look back at what we said about .(ﺀ) carrier, or a ‘bearer’, of another letter: hamza hamza. Later we will discuss hamza in more detail. Here we will go through one of the most common uses of hamza: its combination with 'alif at the beginning or a word. One of the rules of the Arabic language is that no word can begin with a vowel. Many Arabic words may sound to the beginner as though they start with a vowel, but in fact they begin with a glottal stop: that little catch in the voice that is represented by hamza. -

SUFISM AS the CORE of ISLAM: a Review of Imam Junayd Al-Baghdadi's Concept of Tasawwuf

Teosofia: Indonesian Journal of Islamic Mysticism, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2020, pp. 171-192 e-ISSN: 2540-8186; p-ISSN: 2302-8017 DOI: 10.21580/tos.v9i2.6170 SUFISM AS THE CORE OF ISLAM: A Review of Imam Junayd Al-Baghdadi’s Concept of Tasawwuf Cucu Setiawan UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung [email protected] Maulani UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung [email protected] Busro UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung [email protected] Abstract: This paper studies the thoughts of Abu ‘l-Qasim al-Junaid ibn Muhamad ibn Al-Junayd al-Khazzaz al-Qawariri Nihawandi al-Baghdadi, one of the prominent figures during the early development of Sufism, or also known in Arabic as tasawwuf. This study attempts to find a confluence between tasawwuf and Islam, on the basis that Islamic teachings are going through degradation in meanings and tasawwuf is often considered as a bid’ah (heresy) in Islamic studies. This research used a library research method and Junayd al-Baghdadi’s treatise, Rasail Junaid, as the primary data source. This study concludes that tasawwuf is not only an aspect or a segment of Islamic teachings, but it is the core of Islam itself as a religion. There are three central theories of tasawwuf by Junayd al-Baghdadi: mitsaq (covenant), fana (annihilation of self), and tawhid (unification). Based on these three theories, we can conclude that Junayd al- Baghdadi succeeded in conciliating the debate among tasawwuf and fiqh scholars. He also managed to knock down the stigma of tasawwuf as a heresy. His thoughts redefine tasawwuf into a simple and acceptable teaching for Muslims. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

A CRITICAL TRANSLATION OF THE ARTICLE ON THE HORSE FROM AL-DAMIRI'S "HAYAT AL-HAYAWAN AL-KUBRA.". Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors McNeil, Kimberley Carole. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 08:25:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/274826 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. -

Rethinking Totemism in Semitic Traditions Onomastics and The

Hekmat Dirbas Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands Onomastics and the Reconstruction of the Past: Rethinking Totemism in Semitic Traditions Voprosy onomastiki, 2019, Vol. 16, Issue 1, pp. 19–35 DOI: 10.15826/vopr_onom.2019.16.1.002 Language of the article: English ___________________________________________ Hekmat Dirbas Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands Onomastics and the Reconstruction of the Past: Rethinking Totemism in Semitic Traditions Вопросы ономастики. 2019. Т. 16. № 1. С. 19–35 DOI: 10.15826/vopr_onom.2019.16.1.002 Язык статьи: английский Downloaded from: http://onomastics.ru DOI: 10.15826/vopr_onom.2019.16.1.002 Hekmat Dirbas UDC 811.444’373.4 + 39(=411) + 572 Leiden University Leiden, Netherlands ONOMASTICS AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE PAST: RETHINKING TOTEMISM IN SEMITIC TRADITIONS This paper addresses the theory that ancient Semitic proper names derived from animal names may testify to the culture of totemism. This theory, elaborated fi rst in the works of Wil- liam Robertson Smith in the late 19th century, has recently re-emerged in scholarly discussion. However, researching the onomastic material provided by historical sources in four Semitic languages (Amorite, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic), the author argues that the theory in ques- tion is highly implausible. Particular attention is given to Amorite compound names containing the element Ditāna, the Aramaic name Ara/ām, presumably derived from ri’m ‘wild bull,’ and to Arabic personal names of zoonymic origin which are sometimes considered as derived from tribal names. The paper fi nds that there is neither any evidence linking the names in question with the social groups known in these languages nor is there a single reference to animals as symbolic ancestors or the like. -

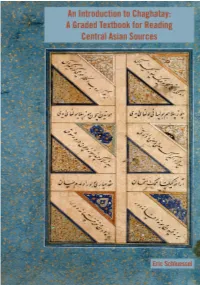

Mpub10110094.Pdf

An Introduction to Chaghatay: A Graded Textbook for Reading Central Asian Sources Eric Schluessel Copyright © 2018 by Eric Schluessel Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. Published in the United States of America by Michigan Publishing Manufactured in the United States of America DOI: 10.3998/mpub.10110094 ISBN 978-1-60785-495-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60785-496-8 (e-book) An imprint of Michigan Publishing, Maize Books serves the publishing needs of the University of Michigan community by making high-quality scholarship widely available in print and online. It represents a new model for authors seeking to share their work within and beyond the academy, offering streamlined selection, production, and distribution processes. Maize Books is intended as a complement to more formal modes of publication in a wide range of disciplinary areas. http://www.maizebooks.org Cover Illustration: "Islamic Calligraphy in the Nasta`liq style." (Credit: Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/chengwfg/, licensed under CC BY 4.0) Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction vi How to Read the Alphabet xi 1 Basic Word Order and Copular Sentences 1 2 Existence 6 3 Plural, Palatal Harmony, and Case Endings 12 4 People and Questions 20 5 The Present-Future Tense 27 6 Possessive -

Accordance Fonts(November 2010)

Accordance Fonts (November 2010) Contents Installing the Fonts . 2. OS X Font Display in Accordance and above . 2. Font Display in Other OS X Applications . 3. Converting to Unicode . 4. Other Font Tips . 4. Helena Greek Font . 5. Additional Character Positions for Helena . 5. Helena Greek Font . 6. Yehudit Hebrew Font . 7. Table of Hebrew Vowels and Other Characters . 7. Yehudit Hebrew Font . 8. Notes on Yehudit Keyboard . 9. Table of Diacritical Characters(not used in the Hebrew Bible) . 9. Table of Accents (Cantillation Marks, Te‘amim) — see notes at end . 9. Notes on the Accent Table . 1. 2 Peshitta Syriac Font . 1. 3 Characters in non-standard positions . 1. 3 Peshitta Syriac Font . 1. 4 Syriac vowels, other diacriticals, and punctuation: . 1. 5 Rosetta Transliteration Font . 1. 6 Character Positions for Rosetta: . 1. 6 Sylvanus Uncial/Coptic Font . 1. 8 Sylvanus Uncial Font . 1. 9 MSS Font for Manuscript Citation . 2. 1 MSS Manuscript Font . 2. 2 Salaam Arabic Font . 2. 4 Characters in non-standard positions . 2. 4 Salaam Arabic Font . 2. 5 Arabic vowels and other diacriticals: . 2. 6 Page 1 Accordance Fonts OS X font Seven fonts are supplied for use with Accordance: Helena for Greek, Yehudit for Hebrew, Peshitta for Syriac, Rosetta for files transliteration characters, Sylvanus for uncial manuscripts, and Salaam for Arabic . An additional MSS font is used for manuscript citations . Once installed, the fonts are also available to any other program such as a word processor . These fonts each include special accents and other characters which occur in various overstrike positions for different characters . -

Jihad in a World of Sovereigns: Law, Violence, and Islam in the Bosnia Crisis

Law & Social Inquiry Volume 41, Issue 2, 371–401, Spring 2016 Jihad in a World of Sovereigns: Law, Violence, and Islam in the Bosnia Crisis Darryl Li This article argues that jihads waged in recent decades by “foreign fighter” volunteers invoking a sense of global Islamic solidarity can be usefully understood as attempts to enact an alternative to the interventions of the “International Community.” Drawing from ethnographic and archival research on Arab volunteers who joined the 1992–1995 war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, this article highlights the challenges and dilemmas facing such jihad fighters as they maneuvered at the edges of diverse legal orders, including international and Islamic law. Jihad fighters appealed to a divine authority above the global nation-state order while at the same time rooting themselves in that order through affiliation with the sovereign and avowedly secular nation-state of Bosnia-Herzegovina. This article demonstrates an innovative approach to law, violence, and Islam that critically situates states and nonstate actors in relation to one another in transnational perspective. INTRODUCTION In recent decades, the phenomenon of jihad has attracted widespread notori- ety, especially insofar as the term has been invoked by transnational nonstate groups fighting in various conflicts. In Afghanistan, Chechnya, Iraq, Somalia, Syria, and elsewhere, so-called foreign fighter Muslim volunteers have gathered from all over the world in the name of waging jihad. Such foreign fighters have been the paradigmatic enemy invoked by the United States and other governments to justify their respective campaigns against alleged terrorism. What is the relationship between jihad and law in today’s world? Jihad is com- monly understood as entailing a repudiation of secular formsB of law in favor of a commitment to imposing classical Islamic law, or the sharı¯a. -

Sectarianism in the Middle East

Sectarianism in the Middle East Implications for the United States Heather M. Robinson, Ben Connable, David E. Thaler, Ali G. Scotten C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1681 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9699-9 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims attend prayers during Eid al-Fitr as they mark the end of the fasting month of Ramadan, at the site of a suicide car bomb attack over the weekend at the shopping area of Karrada, in Baghdad, Iraq, July 6, 2016. REUTERS/Thaier Al-Sudani Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. -

The University of Chicago Poetry

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO POETRY AND PEDAGOGY: THE HOMILETIC VERSE OF FARID AL-DIN ʿAṬṬÂR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY AUSTIN O’MALLEY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2017 © Austin O’Malley 2017 All Rights Reserved For Nazafarin and Almas Table of Contents List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................vi Note on Transliteration ...................................................................................................................vii Acknowledgments...........................................................................................................................viii Introduction..........................................................................................................................................1 I. ʿAṭṭâr, Preacher and Poet.................................................................................................................10 ʿAṭṭâr’s Oeuvre and the Problem of Spurious Atributions..............................................12 Te Shiʿi ʿAṭṭâr.......................................................................................................................15 Te Case of the Wandering Titles.......................................................................................22 Biography and Social Milieu....................................................................................................30 -

The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1995 The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco Beebe Bahrami University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, European History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Bahrami, Beebe, "The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco" (1995). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1176. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1176 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1176 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco Abstract This thesis investigates the problem of how an historical identity persists within a community in Rabat, Morocco, that traces its ancestry to Spain. Called Andalusians, these Moroccans are descended from Spanish Muslims who were first forced to convert to Christianity after 1492, and were expelled from the Iberian peninsula in the early seventeenth century. I conducted both ethnographic and historical archival research among Rabati Andalusian families. There are four main reasons for the persistence of the Andalusian identity in spite of the strong acculturative forces of religion, language, and culture in Moroccan society. First, the presence of a strong historical continuity of the Andalusian heritage in North Africa has provided a dominant history into which the exiled communities could integrate themselves. Second, the predominant practice of endogamy, as well as other social practices, reinforces an intergenerational continuity among Rabati Andalusians. Third, the Andalusian identity is a single identity that has a complex range of sociocultural contexts in which it is both meaningful and flexible. -

"A Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Kurdish Scholar in South Africa: Abu

"A nineteenth-century Ottoman Kurdish scholar in South Africa: Abu Bakr Efendi", first published as "A nineteenth-century Kurdish scholar in South Africa", in: Martin van Bruinessen, Mullas, Sufis and heretics: the role of religion in Kurdish society. Collected articles. Istanbul: The Isis Press, 2000, pp. 133-141. A nineteenth-century Ottoman Kurdish scholar in South Africa: Abu Bakr Efendi Martin van Bruinessen Coming from a region where the three major languages of Islam meet, Kurdish `ulama have often played the role of cultural brokers between the Arabic, Persian and Turkish speaking worlds. Scholars and mystics such as Ibrahim al-Kurani, Mawlana Khalid, Muhammad Amin al-Kurdi and Said-i Nursi played important roles as disseminators of mystical ideas across linguistic boundaries, from India and Iran to the Turkish and Arab worlds and hence to other parts of the world of Islam (van Bruinessen 1998). Perhaps even more remarkable than these well-known mystics is the feat of cultural brokerage performed by the Kurdish scholar Abu Bakr Efendi from southern Kurdistan, who in the 1860’s settled in South Africa and wrote a book on the religious obligations of Islam in the local Dutch dialect for the benefit of the ‘Malay’ Muslim community of South Africa. 1 This somewhat elusive scholar arrived in Cape Town in 1862, as an emissary of the Ottoman Sultan Abdülaziz, 2 in order to teach Islamic law and doctrine to the Muslim community and to resolve certain religious conflicts that were dividing that community. He taught Arabic but also learnt the language of the local community, Afrikaans (which is a dialect of Dutch), and he wrote a major work, Bayan al-din , in the latter language, adapting to this purpose the Perso-Arabic alphabet.