The End of Wars As the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebecca Futo Kennedy

Rebecca Futo Kennedy, PhD Associate Professor, Department of Classics, Women’s and Gender Studies, and Environmental Studies, Denison University Director, Denison Museum PO Box 810 Granville, OH 43023 (740) 587-8657 (office); [email protected] EDUCATION The Ohio State University; Ph.D. Greek and Latin June 2003 The Ohio State University; M.A. Greek and Latin June 1999 UC-San Diego; B.A. Classical Studies March 1997 EMPLOYMENT HISTORY • Denison University: Assistant Professor, 2009-2015; Associate Professor, 2015-present • Denison Museum: Interim Director, 2015-2016; Director, 2016-present • Union College: Visiting Assistant Professor, 2008-2009 • The George Washington University: Lecturer/Visiting Assistant Professor, 2005-2008 • Howard University: Assistant Professor, 2003-2005 PUBLICATIONS Research Interests: Political, social, and intellectual history of classical Athens; Athenian tragedy and oratory; Greek and Roman historiography; Race/ethnicity, gender, and identity formation in the ancient Mediterranean; Geography and environment in ancient Greece; Modern reception of ancient theories of human diversity (race/ethnicity); Immigration in Archaic and Classical Greece--law and history Monographs: •Immigrant Women in Athens: Gender, Ethnicity, and Citizenship in the Classical City (Routledge USA, May 2014). Reviewed in Classical Journal On-line, POLIS, Clio (in French), Journal of Hellenic Studies, Classical World, Sehepunkte, Kleio-Historia (in German). •Athena’s Justice: Athena, Athens and the Concept of Justice in Greek Tragedy, Lang Classical Series, Vol. 16 (Peter Lang, 2009). Reviews: Classical Review; Greece & Rome; L'Antiquite Classique (in French); Euphrosyne (in Portuguese); Listy filologické (in Czech). •In progress: • Book on race/ethnicity in classical antiquity and its contemporary legacy; commissioned by Johns Hopkins University Press (under contract and in progress) Edited Volumes: •Co-editor, The Routledge Handbook to Identity and the Environment in the Classical and Medieval Worlds (with Molly Jones-Lewis; Routledge UK, 2016). -

Politics and Policy in Corinth 421-336 B.C. Dissertation

POLITICS AND POLICY IN CORINTH 421-336 B.C. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by DONALD KAGAN, B.A., A.M. The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by: Adviser Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD ................................................. 1 CHAPTER I THE LEGACY OF ARCHAIC C O R I N T H ....................7 II CORINTHIAN DIPLOMACY AFTER THE PEACE OF NICIAS . 31 III THE DECLINE OF CORINTHIAN P O W E R .................58 IV REVOLUTION AND UNION WITH ARGOS , ................ 78 V ARISTOCRACY, TYRANNY AND THE END OF CORINTHIAN INDEPENDENCE ............... 100 APPENDIXES .............................................. 135 INDEX OF PERSONAL N A M E S ................................. 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................... 145 AUTOBIOGRAPHY ........................................... 149 11 FOREWORD When one considers the important role played by Corinth in Greek affairs from the earliest times to the end of Greek freedom it is remarkable to note the paucity of monographic literature on this key city. This is particular ly true for the classical period wnere the sources are few and scattered. For the archaic period the situation has been somewhat better. One of the first attempts toward the study of Corinthian 1 history was made in 1876 by Ernst Curtius. This brief art icle had no pretensions to a thorough investigation of the subject, merely suggesting lines of inquiry and stressing the importance of numisihatic evidence. A contribution of 2 similar score was undertaken by Erich Wilisch in a brief discussion suggesting some of the problems and possible solutions. This was followed by a second brief discussion 3 by the same author. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School REMEMBERING JIMMY CARTER THE RHETORICAL EVOCATIONS OF PRESIDENTIAL MEMORIES A Thesis in Communication Arts and Sciences by Brandon M. Johnson 2020 Brandon M. Johnson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2020 The thesis of Brandon M. Johnson was reviewed and approved by the following: Mary E. Stuckey Professor, Communication Arts and Sciences Thesis Advisor Stephen H. Browne Liberal Arts Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Michael J. Steudeman Assistant Professor of Rhetoric and Director of CAS100A Denise H. Solomon Head and Liberal Arts Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences iii ABSTRACT This thesis is an analysis of the public memory of Jimmy Carter and the way the historical resources of his presidency (including his perceived moral character) are interpreted and evoked as a shorthand for presidential failure by associating him with a rhetoric of weakness. Broadly, I consider the nature of presidential memory, asking how a presidency passes from history to memory. I suggest that presidential histories serve as inventional resources in the present, with rhetors evoking interpretations of the past as rhetorical appeals. These appeals are acts of memory, and analyzing how they function discursively and are deployed strategically draws out how presidential memory works and what implications it has to presidential rhetoric. The different strategies used in remembering the presidency of Jimmy Carter are useful texts for rhetorically critiquing this process because Carter is often deployed as a rhetorical shorthand, providing a representative example of interpreting presidential pasts. I begin by considering the evolving scholarship and historiography on Carter and conceptualizing how presidential pasts can be interpreted in the present through acts of remembering. -

The Art of the Deal for North Korea: the Unexplored Parallel Between Bush and Trump Foreign Policy*

International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Vol. 26, No. 1, 2017, 53–86. The Art of the Deal for North Korea: The Unexplored Parallel between Bush and Trump Foreign Policy* Soohoon Lee ‘Make America Great Again,’ has been revived while ‘America First’ and ‘peace through strength,’ have been revitalized by the Trump admin istration. Americans and the rest of the world were shocked by the dramatic transformation in U.S. foreign policy. In the midst of striking changes, this research analyzes the first hundred days of the Trump administration’s foreign policy and aims to forecast its prospects for North Korea. In doing so, the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy creeds, ‘American exceptionalism’ and ‘peace through strength,’ are revisited and compared with that of Trump’s. Beyond the similarities and differences found between the two administrations, the major finding of the analysis is that Trump’s profitoriented nature, through which he operated the Trump Organization for nearly a half century, has indeed influenced the interest- oriented nature in his operating of U.S. foreign policy. The prospects for Trump’s policies on North Korea will be examined through a business sensitive lens. Keywords: Donald Trump, U.S Foreign Policy, North Korea, America First, Peace through Strength Introduction “We are so proud of our military. It was another successful event… If you look at what’s happened over the eight weeks and compare that to what’s happened over the last eight years, you'll see there’s a tremen * This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF2016S1A3A2924968). -

Andrew J. Bacevich

ANDREW J. BACEVICH Department of International Relations Boston University 152 Bay State Road Boston, Massachusetts 02215 Telephone (617) 358-0194 email: [email protected] CURRENT POSITION Boston University Professor of History and International Relations, College of Arts & Sciences Professor, Kilachand Honors College EDUCATION Princeton University, M. A., American History, 1977; Ph.D. American Diplomatic History, 1982 United States Military Academy, West Point, B.S., 1969 FELLOWSHIPS Columbia University, George McGovern Fellow, 2014 Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame Visiting Research Fellow, 2012 The American Academy in Berlin Berlin Prize Fellow, 2004 The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Visiting Fellow of Strategic Studies, 1992-1993 The John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University National Security Fellow, 1987-1988 Council on Foreign Relations, New York International Affairs Fellow, 1984-1985 PREVIOUS APPOINTMENTS Boston University Director, Center for International Relations, 1998-2005 The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Professorial Lecturer; Executive Director, Foreign Policy Institute, 1993-1998 School of Arts and Sciences, Johns Hopkins University Professorial Lecturer, Department of Political Science, 1995-19 United States Military Academy, West Point Assistant Professor, Department of History, 1977-1980 1 PUBLICATIONS Books and Monographs Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country. New York: Metropolitan Books (2013); audio edition (2013). The Short American Century: A Postmortem. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (2012). (editor) Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War. New York: Metropolitan Books (2010); audio edition (2010); Chinese edition (2011); Korean edition (2013). The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism. -

THE UNITED STATES INSTITUTE of PEACE Sreeram Chaulia

International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 14, Number 1, Spring/Summer 2009 ONE STEP FORWARD, TWO STEPS BACKWARD: THE UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE Sreeram Chaulia Abstract This essay applies critical theories of knowledge-producing institutions to demonstrate the utility of a conceptual framework about elite institutions that are deployed by powerful authorities to suppress anti- establishment knowledge. It asserts that knowledge-centric institutions which are appendages of power structures act to consume radical grassroots ideas in society and replace them with sympathy, loyalty and obedience to the establishment. It uses the case of the United States Institute of Peace to test the framework and show how this think tank has been consistently used by US foreign policy elites as an instrument to counter the peace movement. The conclusion offers thoughts on structural conditions through which more objective and people-centric think tanks can be built. Knowledge-Producing Institutions and Hegemony Hegemonic power structures, be they domestic or international, rest on a tissue of ideas that is beefed up with economic and military muscle. Rationality dictates that powerful actors in a society or international system cannot permanently rely on coercion to achieve their ends. This is due to the impossibility of policing each nook and cranny of the space that is subject to rule, as well as the natural instinct of the weak to attempt “everyday forms of resistance” (Scott, 1985). No system of rule can completely avoid slippage and subversion at the margins, but it can employ a vast intellectual apparatus to ensure that dissenting knowledge is contained at manageable levels or quarantined, so that the whole forest does not catch flame. -

Reclaiming Peace in International Relations

Reclaiming Peace in International Relations Reclaiming Peace in International Relations Oliver P. Richmond* What is peace? This basic question often appears in contemporary orthodoxy to have been settled in favour of the ‘liberal peace’. Yet, this has, in many post-conflict settings, proved to create a ‘virtual peace’- empty states and institutions which are ambivalent about everyday life. In this context peace is widely referred to but rarely defined. Though the concept of peace is often assumed to be normatively irreproachable, formative in the founding of the discipline, and central to the agendas of liberal states, it has rarely been directly approached as an area of study within IR. This essay endeavours to illustrate how developing accounts of peace helps chart the different theoretical and methodological contributions in IR, and the complex issues that then emerge. These include the pressing problem of how peace efforts become sustainable rather than merely inscribed in international and state-level diplomatic and military frameworks. This also raises issues related to an ontology of peace, culture, development, agency and structure, not just in terms of the representations of the world, and of peace, presented in the discipline, but in terms of the sovereignty of the discipline itself and its implications for everyday life. In an interdisciplinary and pluralist field of study – as IR has now become – concepts of peace and their sustainability are among those that are central. This raises the question of what the discipline is for, if not for peace? This paper explores such issues in the context of orthodox and critical IR theory, methods, and ontology, and offers some thoughts about the implications of placing peace at the centre of IR. -

1 the Great Communicator and the Beginning of the End of the Cold War1 by Ambassador Eric S. Edelman President Ronald Reagan Is

The Great Communicator and the Beginning of the End of the Cold War1 By Ambassador Eric S. Edelman President Ronald Reagan is known as the “Great Communicator,” a soubriquet that was awarded to him by New York Times columnist Russell Baker, and which stuck despite Reagan’s disclaimer in his farewell address that he “wasn’t a great communicator” but that he had “communicated great things.” The ideas which animated Reagan’s vision were given voice in a series of extraordinary speeches, many of them justly renowned. Among them are his “Time for Choosing” speech in 1964, his “Shining City on a Hill” speech to CPAC in 1974, his spontaneous remarks at the conclusion of the Republican National Convention in 1976 and, of course, his memorable speeches as President of the United States. These include his “Evil Empire” speech to the National Association of Evangelicals, his remarks at Westminster in 1982, his elegiac comments commemorating the 40th anniversary of the D-Day invasion and mourning the Challenger disaster, and his Berlin speech exhorting Mikhail Gorbachev to “Tear Down this Wall” in 1987, which Time Magazine suggested was one of the 10 greatest speeches of all time.2 Curiously, Reagan’s address to the students of Moscow State University during the 1988 Summit with Mikhail Gorbachev draws considerably less attention today despite the fact that even normally harsh Reagan critics hailed the speech at the time and have continued to cite it subsequently. The New York Times, for instance, described the speech as “Reagan’s finest oratorical hour” and Princeton’s liberal historian Sean Wilentz has called it “the symbolic high point of Reagan’s visit…. -

177 Whenever I Am Called to Defend the Importance of My Job And

Book Reviews 177 Jennifer T. Roberts, (2017) The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece. New York: Oxford University Press. xxviii + 416 pages. ISBN: 9780199996643 (hbk), $34.95. Whenever I am called to defend the importance of my job and the relevance of ancient history (something I have to do all too often these days), I revert back to Thucydides, who wrote his history of the Peloponnesian War to be a ‘pos- session for all time’. According to the ‘human thing’, or kata to anthrōpinon in the Greek, Thucydides thought that the motivations and personalities – along perhaps with the events themselves – of the Peloponnesian War would hap- pen time and time again throughout human history. I think that Thucydides is more or less right, and that aside from offering a powerful and provocative lit- erary meditation on a specific conflict and set of characters, he sheds light on the human condition like few other authors have, making his work eminently applicable today. I am heartened, therefore, to find that Jennifer T. Roberts takes a similar view of Thucydides and the war he recorded. In the preface to her book, Roberts makes a passionate case for the con- tinuing relevance of the Peloponnesian War, starting with her own father’s wartime experiences and surveying the many other works – academic and popular – that have compared Thucydides’ war to the modern world. But, be- fore beginning her readable history of the Peloponnesian War geared mostly to the newcomer to that period of Greek history, Roberts argues at the outset that, invaluable as his work is, Thucydides ought now to be ‘uncoupled’ from the his- tory of the war (p. -

The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War Free

FREE THE OUTBREAK OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR PDF Donald M. Kagan | 440 pages | 19 Nov 2015 | Cornell University Press | 9780801495564 | English | Ithaca, United States Peloponnesian War - Wikipedia Kagan offers a new evaluation of the origins and causes of the Peloponnesian War, based on evidence produced by modern scholarship and on a careful reconsideration The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War the ancient texts. He focuses his study on the question: Was the war inevitable, or could it have been avoided? Kagagn takes issue with Thucydides's view that the war was inevitable, that the rise of the Athenian Empire in a world with an existing rival power made a clash between the two a certainty. He further examines the evidence to see what decisions were made that led to war, at each point asking whether a different decision would have been possible. Read more Read less. Pre-order Books. Order now from our extensive selection of books coming soon with Pre-order Price Guarantee. If the Amazon. Shop now. Frequently bought together. Add all three to Cart. These items are shipped from and sold by different sellers. Show details. Customers who bought this item also bought. Page 1 of 1 Start over Page 1 of 1. Previous page. Donald Kagan. Usually dispatched within 3 to 4 days. Only 3 left in stock. The Peloponnesian War. Only 4 left in stock more on the way. A History Of My Times. Next page. Don't have a Kindle? Review ''The temptation to acclaim Kagan's four volumes as the foremost work of history produced in North America in the twentieth century is vivid. -

Fighting Back Against the Cold War: the American Committee on East-West Accord And

Fighting Back Against the Cold War: The American Committee on East-West Accord and the Retreat from Détente A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Benjamin F.C. Wallace May 2013 © 2013 Benjamin F.C. Wallace. All Rights Reserved 2 This thesis titled Fighting Back Against the Cold War: The American Committee on East-West Accord and the Retreat from Détente by BENJAMIN F.C. WALLACE has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Chester J. Pach Associate Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT WALLACE, BENJAMIN F.C., M.A., May 2013, History Fighting Back Against the Cold War: The American Committee on East-West Accord and the Retreat From Détente Director of Thesis: Chester J. Pach This work traces the history of the American Committee on East-West Accord and its efforts to promote policies of reduced tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s. This organization of elite Americans attempted to demonstrate that there was support for policies of U.S.-Soviet accommodation and sought to discredit its opponents, especially the Committee on the Present Danger. This work argues that the Committee, although largely failing to achieve its goals, illustrates the wide-reaching nature of the debate on U.S.-Soviet relations during this period, and also demonstrates the enduring elements of the U.S.-Soviet détente of the early 1970s. -

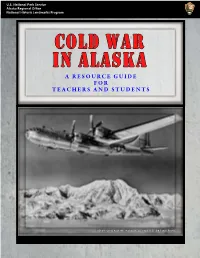

Cold War in Alaska a Resource Guide for Teachers and Students

U.S. National Park Service Alaska Regional Office National Historic Landmarks Program COLD WAR IN ALASKA A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS RB-29 flying past Mt. McKinley, ca. 1948, U.S. Air Force Photo. DANGER Colors, this page left, mirror those used in the first radiation symbol designed by Cyrill Orly in 1945. The three-winged icon with center dot is "Roman violet,"a color used by early Nuclear scientists to denote a very precious item. The "sky blue" background was intended to create an arresting contrast. Original symbol (hand painted on wood) at the Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Radiation_symbol_-_James_V._For- restal_Building_-_IMG_2066.JPG ACTIVE U.S. Army soldiers on skis, Big Delta, Alaska, April 9, 1952, P175-163 Alaska State Library U.S. Army Signal Corps Photo Collection. U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Alaska Regional Office National Historic Landmarks Program First Printing 2014 Introduction Alaska’s frontline role during the Cold War ushered in unprecedented economic, technological, political, and social changes. The state’s strategic value in defending our nation also played a key role in its bid for statehood. Since the end of the Cold War, Alaska’s role and its effects on the state have received increasing focus from historians, veterans, and longtime Alaskans. This resource guide is designed to help students and teachers in researching the Cold War in Alaska, and to provide basic information for anyone who is interested in learning more about this unique history. The guide begins with a map of Cold War military sites in Alaska and a brief summary to help orient the reader.