THE VULNERABLE Our Military Problems and How to Fix Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 12, 2006 the Honorable John Warner, Chairman The

GENERAL JOHN SHALIKASHVILI, USA (RET.) GENERAL JOSEPH HOAR, USMC (RET.) ADMIRAL GREGORY G. JOHNSON, USN (RET.) ADMIRAL JAY L. JOHNSON, USN (RET.) GENERAL PAUL J. KERN, USA (RET.) GENERAL MERRILL A. MCPEAK, USAF (RET.) ADMIRAL STANSFIELD TURNER, USN (RET.) GENERAL WILLIAM G. T. TUTTLE JR., USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL DANIEL W. CHRISTMAN, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL PAUL E. FUNK, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL ROBERT G. GARD JR., USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL JAY M. GARNER, USA (RET.) VICE ADMIRAL LEE F. GUNN, USN (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL ARLEN D. JAMESON, USAF (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL CLAUDIA J. KENNEDY, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL DONALD L. KERRICK, USA (RET.) VICE ADMIRAL ALBERT H. KONETZNI JR., USN (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL CHARLES OTSTOTT, USA (RET.) VICE ADMIRAL JACK SHANAHAN, USN (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL HARRY E. SOYSTER, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL PAUL K. VAN RIPER, USMC (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL JOHN BATISTE, USA (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL EUGENE FOX, USA (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL JOHN L. FUGH, USA (RET.) REAR ADMIRAL DON GUTER, USN (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL FRED E. HAYNES, USMC (RET.) REAR ADMIRAL JOHN D. HUTSON, USN (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL MELVYN MONTANO, ANG (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL GERALD T. SAJER, USA (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL MICHAEL J. SCOTTI JR., USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL DAVID M. BRAHMS, USMC (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL JAMES P. CULLEN, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL EVELYN P. FOOTE, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL DAVID R. IRVINE, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN H. JOHNS, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL RICHARD O’MEARA, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL MURRAY G. SAGSVEEN, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN K. SCHMITT, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL ANTHONY VERRENGIA, USAF (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL STEPHEN N. -

H Salute Their Service, Honor Their Hope H

H SALUTE THEIR SERVICE, HONOR THEIR HOPE H TO PRESERVE THE LEGACY OF PATRIOTISM AND THE SACRIFICE OF OUR GREATEST GENERATION It was on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, Dear Friends, 1945, that General MacArthur, We are honored to serve as the Co-Chairs of the 75th Anniversary of the End of World War II Admiral Chester Nimitz and commemoration committee. Alongside our Presenting Sponsor, Linda Hope who represents representatives of the Allied the Bob Hope Legacy as a part of the Bob & Dolores Hope Foundation, we encourage you to join us in commemorating this historic occasion by supporting two seminal events in 2020, Powers accepted Japan’s formal marking the end of the war in Europe and the Pacific. surrender, bringing to an end the Our hope is that these events will preserve our nation’s memory of a time when the United bloodiest war in world history. States persevered with selflessness and courage in the face of tyranny. We also hope to The heartfelt words of General inspire our fellow citizens and freedom-loving people around the world by celebrating the legacy and character of those who have been called America’s “Greatest Generation.” MacArthur, spoken on that day, are still with us: World War II was perhaps the single greatest unification of the American people in our nation’s history. The sacrifices demanded by the global conflict touched every citizen. Military service became commonplace. Americans capable of donning a military uniform “It is my earnest hope, and indeed dutifully raised their hands. -

Legislative Limelight: Investigations by the United States Congress By

Legislative Limelight: Investigations by the United States Congress by John Ignatius Hanley A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Anne Joseph O’Connell Fall 2012 Legislative Limelight: Investigations by the United States Congress © 2012 By John Ignatius Hanley Abstract Legislative Limelight: Investigations by the United States Congress by John Ignatius Hanley Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Academic studies have often emphasized the law-making aspects of Congress to the exclusion of examining how Congress uses its investigative power. This is despite the fact that Congress possesses great power to compel testimony and documents from public and private persons alike, and that exercises of the investigative power are among the most notable public images of Congress. While several recent studies have considered investigations in the context of relations between the executive and legislative branches, far less effort has been committed to looking at how much Congress uses coercive investigative power to gather information on non- governmental actors. I develop several new datasets to examine the historical and recent use of investigations of both governmental and non-governmental institutions. A major component of this work is a comprehensive study of all authorizations of subpoena power granted to committees over the period 1792-1944. I find that for both Executive and outside subjects, divided control of government was positively associated with the volume of investigations in the House, but not in the Senate. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Web Apr 06.Qxp

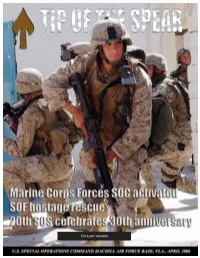

On-Line version TIP OF THE SPEAR Departments Global War On Terrorism Page 4 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command Page 18 Naval Special Warfare Command Page 21 Air Force Special Operations Command Page 24 U.S. Army Special Operations Command Page 28 Headquarters USSOCOM Page 30 Special Operations Forces History Page 34 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command historic activation Gen. Doug Brown, commander, U.S. Special Operations Command, passes the MARSOC flag to Brig. Gen. Dennis Hejlik, MARSOC commander, during a ceremony at Camp Lejune, N.C., Feb. 24. Photo by Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser. Tip of the Spear Gen. Doug Brown Capt. Joseph Coslett This is a U.S. Special Operations Command publication. Contents are Commander, USSOCOM Chief, Command Information not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, Department of Defense or USSOCOM. The content is CSM Thomas Smith Mike Bottoms edited, prepared and provided by the USSOCOM Public Affairs Office, Command Sergeant Major Editor 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., MacDill AFB, Fla., 33621, phone (813) 828- 2875, DSN 299-2875. E-mail the editor via unclassified network at Col. Samuel T. Taylor III Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser [email protected]. The editor of the Tip of the Spear reserves Public Affairs Officer Editor the right to edit all copy presented for publication. Front cover: Marines run out of cover during a short firefight in Ar Ramadi, Iraq. The foot patrol was attacked by a unknown sniper. Courtesy photo by Maurizio Gambarini, Deutsche Press Agentur. Tip of the Spear 2 Highlights Special Forces trained Iraqi counter terrorism unit hostage rescue mission a success, page 7 SF Soldier awarded Silver Star for heroic actions in Afghan battle, page 14 20th Special Operations Squadron celebrates 30th anniversary, page 24 Tip of the Spear 3 GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM Interview with Gen. -

Cyber Warfare a “Nuclear Option”?

CYBER WARFARE A “NUCLEAR OPTION”? ANDREW F. KREPINEVICH CYBER WARFARE: A “NUCLEAR OPTION”? BY ANDREW KREPINEVICH 2012 © 2012 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. About the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, secu- rity policy and resource allocation. CSBA provides timely, impartial, and insight- ful analyses to senior decision makers in the executive and legislative branches, as well as to the media and the broader national security community. CSBA encour- ages thoughtful participation in the development of national security strategy and policy, and in the allocation of scarce human and capital resources. CSBA’s analysis and outreach focus on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to US national security. Meeting these challenges will require transforming the national security establishment, and we are devoted to helping achieve this end. About the Author Dr. Andrew F. Krepinevich, Jr. is the President of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, which he joined following a 21-year career in the U.S. Army. He has served in the Department of Defense’s Office of Net Assessment, on the personal staff of three secretaries of defense, the National Defense Panel, the Defense Science Board Task Force on Joint Experimentation, and the Defense Policy Board. He is the author of 7 Deadly Scenarios: A Military Futurist Explores War in the 21st Century and The Army and Vietnam. -

Army Downsizing Following World War I, World War Ii, Vietnam, and a Comparison to Recent Army Downsizing

ARMY DOWNSIZING FOLLOWING WORLD WAR I, WORLD WAR II, VIETNAM, AND A COMPARISON TO RECENT ARMY DOWNSIZING A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE Military History by GARRY L. THOMPSON, USA B.S., University of Rio Grande, Rio Grande, Ohio, 1989 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 2002 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burder for this collection of information is estibated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burder to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (FROM - TO) 31-05-2002 master's thesis 06-08-2001 to 31-05-2002 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER ARMY DOWNSIZING FOLLOWING WORLD WAR I, WORLD II, VIETNAM AND 5b. -

Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century

US Army TRADOC TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 AA MilitaryMilitary GuideGuide toto TerrorismTerrorism in the Twenty-First Century US Army Training and Doctrine Command TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity - Threats Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 15 August 2007 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. 1 Summary of Change U.S. Army TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 (Version 5.0) A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century Specifically, this handbook dated 15 August 2007 • Provides an information update since the DCSINT Handbook No. 1, A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century, publication dated 10 August 2006 (Version 4.0). • References the U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • References the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Reports on Terrorist Incidents - 2006, dated 30 April 2007. • Deletes Appendix A, Terrorist Threat to Combatant Commands. By country assessments are available in U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • Deletes Appendix C, Terrorist Operations and Tactics. These topics are covered in chapter 4 of the 2007 handbook. Emerging patterns and trends are addressed in chapter 5 of the 2007 handbook. • Deletes Appendix F, Weapons of Mass Destruction. See TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.04. • Refers to updated 2007 Supplemental TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.01, Terror Operations: Case Studies in Terror, dated 25 July 2007. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. 1.02, Critical Infrastructure Threats and Terrorism, dated 10 August 2006. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. -

THE QUIET WAR the US Army in the Korean Demilitarized Zone 1953-2004 Manny Seck 4090116

THE QUIET WAR The US Army in the Korean Demilitarized Zone 1953-2004 Manny Seck 4090116 "There are no memorials inscribed with their names or monuments erected that extol their sacrifice. The battles along the Korean DMZ (1966-69) are for the most part forgotten except by the families of the dead." Major Vandon E. Jenerette US. Army "If we're killed on a patrol or a guard post, crushed in a jeep accident or shot by a nervous GI on the fence, no one will ever write about us in the Times or erect a monument or read a Gettysburg Address over our graves. There's too much going on elsewhere; what we're doing is trivial in comparison. We'll never be part of the national memory." William Hollinger, HHC. 1st/31st Inf. 7th Infantry Division, 1968-1969. “If you have a son overseas, write to him. If you have a son in the Second Infantry Division, pray for him.” Walter Winchell, 1950 The author would respectfully like to thank 1st Sergeant Roy Whitfield, CSM Larry Williams, SGT Ron Rice, MSG Richard Howard, BG Charles Viale, LTC Robert Griggs, SSG Dave Chapman, CSM Jim Howk, SGT Al Garcia, CPT Lee Scripture, Bill Ferguson, Norm Treadway, and many others. These men answered the author’s endless questions, provided maps, photos, and documents, and tolerated the author’s silly jokes. With out soldiers like these, this work would not be possible, and any mistakes in this paper are solely the author’s. I would also like to dedicate this work to PVT. -

Gentlemen Under Fire: the U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 1 June 2008 Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming Elizabeth L. Hillman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Elizabeth L. Hillman, Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming, 26(1) LAW & INEQ. 1 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol26/iss1/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Gentlemen Under Fire: The U.S. Military and "Conduct Unbecoming" Elizabeth L. Hillmant Introduction ..................................................................................1 I. Creating an Officer Class ..................................................10 A. "A Scandalous and Infamous" Manner ...................... 11 B. The "Military Art" and American Gentility .............. 12 C. Continental Army Prosecutions .................................15 II. Building a Profession .........................................................17 A. Colonel Winthrop's Definition ...................................18 B. "A Stable Fraternity" ................................................. 19 C. Old Army Prosecutions ..............................................25 III. Defending a Standing Army ..............................................27 A. "As a Court-Martial May Direct". ............................. 27 B. Democratization and its Discontents ........................ 33 C. Cold War Prosecutions ..............................................36 -

The Revolution in Military Affairs: Prospects and Cautions

THE REVOLUTION IN MILITARY AFFAIRS: PROSPECTS AND CAUTIONS Earl H. Tilford, Jr. June 23, 1995 ******* The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ******* Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5050. Comments also may be conveyed directly to the author by calling commercial (717) 245-4086 or DSN 242-4086. LL FOREWORD The current Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) is taking place against the background of a larger historical watershed involving the end of the Cold War and the advent of what Alvin and Heidi Toffler have termed "the Information Age." In this essay, Dr. Earl Tilford argues that RMAs are driven by more than breakthrough technologies, and that while the technological component is important, a true revolution in the way military institutions organize, equip and train for war, and in the way war is itself conducted, depends on the confluence of political, social, and technological factors. After an overview of the dynamics of the RMA, Dr. Tilford makes the case that interservice rivalry and a reintroduction of the managerial ethos, this time under the guise of total quality management (TQM), may be the consequences of this revolution. In the final analysis, warfare is quintessentially a human endeavor. Technology and technologically sophisticated weapons are only means to an end. -

The End of Wars As the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great

Naval War College Review Volume 53 Article 3 Number 4 Autumn 2000 The ndE of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great Wars of the Twentieth Century Donald Kagan Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Kagan, Donald (2000) "The ndE of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great Wars of the Twentieth Century," Naval War College Review: Vol. 53 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol53/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kagan: The End of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Gr Dr. Donald Kagan is Hillhouse Professor of History and Classics at Yale University. Professor Kagan earned a B.A. in history at Brooklyn College, an M.A. in classics from Brown University, and a Ph.D. in history from Ohio State University; he has been teaching history and classics for over forty years, at Yale since 1969. Professor Kagan has received honorary doctorates of humane let- ters from the University of New Haven and Adelphi University, as well as numerous awards and fellow- ships. He has published many books and articles, in- cluding On the Origins of War and the Preservation of Peace (1995), The Heritage of World Civilizations (1999), The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (1969), “Human Rights, Moralism, and Foreign Pol- icy” (1982), “World War I, World War II, World War III” (1987), “Why Western History Matters” (1994), and “Our Interest and Our Honor” (1997).