Cold War in Alaska a Resource Guide for Teachers and Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elmendorf Air Force Base (Afb)

ELMENDORF AIR FORCE BASE (AFB) Contract Details Contract Type: Energy Efficiency; Energy Savings Performance Contract; Guaranteed Energy Savings; Natural Gas Facility Size: Nearly 800 buildings; Over 9.3 million sq. feet Energy Project Size: Elmendorf Air Force Base, located in Anchorage, Alaska, comprises nearly 800 facilities and spans 9.3 million square feet of multi-use space. Ameresco $48.8 million implemented an ESPC, which included supplying the base with natural gas and decentralizing the heating system. Energy Savings: Customer Benefits (CHPP) with a modern and high-efficiency system. Over 1 million MMBtu The Elmendorf Air Force Base entered a partnership Ameresco’s insightful and thorough review of the with Ameresco to design and implement an energy project concept indicated the infrastructure to support savings performance contract (ESPC). The project the CHPP was failing and too expensive to repair. After Capacity: utilized locally available natural gas as an energy additional discussions concerning security and 5.6 MW component. Ameresco took into consideration the Elmendorf’s future growth projections, converting the setting and brief construction time frame for on-time CHPP to a decentralized heating system with the project completion. Elmendorf achieved its sustain- capability to receive their full electricity requirements ability goals and reduced energy use without redundantly from the local utility became the project’s compromising its mission. This project alone made new direction. Elmendorf’s energy reduction goals and has had a Summary major impact on the Air Force’s goals with annual Thorough consideration to provide the Ameresco developed the new project scope, managed a energy savings of over 1 million MMBtu. -

Hearing National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 Oversight of Previously Authorized Programs Committee on Armed S

i [H.A.S.C. No. 112–111] HEARING ON NATIONAL DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION ACT FOR FISCAL YEAR 2013 AND OVERSIGHT OF PREVIOUSLY AUTHORIZED PROGRAMS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SUBCOMMITTEE ON STRATEGIC FORCES HEARING ON FISCAL YEAR 2013 NATIONAL DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION BUDGET REQUEST FOR MISSILE DEFENSE HEARING HELD MARCH 6, 2012 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 73–437 WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, http://bookstore.gpo.gov. For more information, contact the GPO Customer Contact Center, U.S. Government Printing Office. Phone 202–512–1800, or 866–512–1800 (toll-free). E-mail, [email protected]. SUBCOMMITTEE ON STRATEGIC FORCES MICHAEL TURNER, Ohio, Chairman TRENT FRANKS, Arizona LORETTA SANCHEZ, California DOUG LAMBORN, Colorado JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MO BROOKS, Alabama RICK LARSEN, Washington MAC THORNBERRY, Texas MARTIN HEINRICH, New Mexico MIKE ROGERS, Alabama JOHN R. GARAMENDI, California JOHN C. FLEMING, M.D., Louisiana C.A. DUTCH RUPPERSBERGER, Maryland SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio AUSTIN SCOTT, Georgia TIM MORRISON, Professional Staff Member LEONOR TOMERO, Professional Staff Member AARON FALK, Staff Assistant (II) C O N T E N T S CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF HEARINGS 2012 Page HEARING: Tuesday, March 6, 2012, Fiscal Year 2013 National Defense Authorization Budget Request for Missile Defense ................................................................... 1 APPENDIX: Tuesday, March 6, 2012 .......................................................................................... 33 TUESDAY, MARCH 6, 2012 FISCAL YEAR 2013 NATIONAL DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION BUDGET REQUEST FOR MISSILE DEFENSE STATEMENTS PRESENTED BY MEMBERS OF CONGRESS Sanchez, Hon. Loretta, a Representative from California, Ranking Member, Subcommittee on Strategic Forces ..................................................................... -

Joint Land Use Study

Fairbanks North Star Borough Joint Land Use Study United States Army, Fort Wainwright United States Air Force, Eielson Air Force Base Fairbanks North Star Borough, Planning Department July 2006 Produced by ASCG Incorporated of Alaska Fairbanks North Star Borough Joint Land Use Study Fairbanks Joint Land Use Study This study was prepared under contract with Fairbanks North Star Borough with financial support from the Office of Economic Adjustment, Department of Defense. The content reflects the views of Fairbanks North Star Borough and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Office of Economic Adjustment. Historical Hangar, Fort Wainwright Army Base Eielson Air Force Base i Fairbanks North Star Borough Joint Land Use Study Table of Contents 1.0 Study Purpose and Process................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction....................................................................................................................1 1.2 Study Objectives ............................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Planning Area................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Participating Stakeholders.............................................................................................. 4 1.5 Public Participation........................................................................................................ 5 1.6 Issue Identification........................................................................................................ -

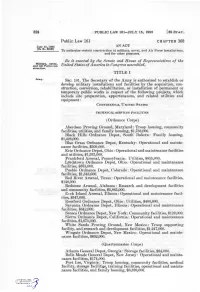

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

Resource Utilization in Unalaska, Aleutian Islands, Alaska

RESOURCE UTILIZATION IN UNALASKA, ALEUTIAN ISLANDS, ALASKA Douglas W. Veltre, Ph. D. Mary J. Veltre, B.A. Technical Paper Number 58 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence October 23, 1982 Contract 824790 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report would not have been possible to produce without the generous support the authors received from many residents of Unalaska. Numerous individuals graciously shared their time and knowledge, and the Ounalashka Corporation,. in particular, deserves special thanks for assistance with housing and transportation. Thanks go too to Linda Ellanna, Deputy Director of the Division of Subsistence, who provided continuing support throughout this project, and to those individuals who offered valuable comments on an earlier draft of this report. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. ii Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 Purpose ..................... 1 Research objectives ............... 4 Research methods 6 Discussion of rese~r~h'm~tho~oio~y' ........ ...... 8 Organization of the report ........... 10 2 BACKGROUNDON ALEUT RESOURCE UTILIZATION . 11 Introduction ............... 11 Aleut distribuiiin' ............... 11 Precontact resource is: ba;tgr;ls' . 12 The early postcontact period .......... 19 Conclusions ................... 19 3 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND. 23 Introduction ........................... 23 The precontact'plrioi . 23 The Russian period ............... 25 The American period ............... 30 Unalaska community profile. ........... 37 Conclusions ................... 38 4 THE NATURAL SETTING ............... -

An Air Force Almanac

THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE IN FACTS AND FIGURES An Air Force Almanac On the following pages appears a variety of infor- Affairs in its role as liaison with Air Staff agencies porting unit reports or in the "Guide to Major mation and statistical material about the US Air in bringing up to date the comparable data from USAF Installations Worldwide") because of differ- Force-its people, organization, equipment, fund- last year's "Almanac." ent cutoff dates, rounding, differing methods of ing, activities, bases, and heroes. This "Almanac" A word of caution: Personnel figures that ap- reporting, or categories of personnel that are ex- section was compiled by the staff of AIR FORCE pear in this section in different forms will not agree cluded in some cases. These figures do illustrate Magazine. We especially acknowledge the help of (nor will they always agree with figures in com- trends, however, and may be helpful in placing the Secretary of the Air Force Office of Public mand, separate operating agency, and direct re- force fluctuations in perspective. -THE EDITORS USAF-EVOLUTION OF THE NAME AND THE SERVICE'S LEADERS' DESIGNATION FROM TO COMMANDER (at highest rank) TITLE FROM TO Aeronautical Div., US Signal Corps Aug. 1, 1907 July 18, 1914 Brig. Gen. James Men Chief Signal Officer Aug 1, 1907 Feb. 13. 1913 Brig. Gen. George P. Scdven Chief Signal Officer Feb. 13, 1913 July 18, 1914 Aviation Section, US Signal Corps July 18, 1914 May 24. 1918 Brig, Gen. George P Scriven Chief Signal Officer July 18. 1914 Feb. 13. 1917 Maj. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Alaska Association for Historic Preservation - Nike Site Summit Tourism Development Project

Total Project Snapshot Report 2012 Legislature TPS Report 58433v1 Agency: Commerce, Community and Economic Development Grants to Named Recipients (AS 37.05.316) Grant Recipient: Alaska Association for Historic Federal Tax ID: 920085097 Preservation Project Title: Project Type: Remodel, Reconstruction and Upgrades Alaska Association for Historic Preservation - Nike Site Summit Tourism Development Project State Funding Requested: $50,000 House District: Anchorage Areawide (16-32) Future Funding May Be Requested Brief Project Description: Stabilize Buildings at Nike Site Summit Historic District in preparation for public tours. Funding Plan: Total Project Cost: $215,000 Funding Already Secured: ($5,000) FY2013 State Funding Request: ($50,000) Project Deficit: $160,000 Funding Details: FONSS is actively fundraising and seeking in-kind donations to continue the work to stabilize the Launch Control Building and Guided Missile Maintenance Facility. Total project cost as estimated by the Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER) is approximately $524,000. Our estimate of $407,670 is based on different assumptions for treating the buildings. Detailed Project Description and Justification: In preparation for guided tours of the Nike Site Summit Historic District scheduled to begin in the fall of 2012, FONSS began building stabilization of the Launch Control Building and the Guided Missile Maintenance Building in the summer of 2011. This followed successful completion of restoration of 3 Sentry Buildings and preliminary roof repairs at two Launch buildings during the summer of 2010 by volunteers. Donations from vendors, in-kind equipment loans and FONSS members have so far paid for repairs, but additional funds are needed to cover the "big jobs" that remain, as follows: Launch Control Building - The objective of stabilization is to seal the building from the elements, restore the exterior of the building to its historic Cold War appearance, and abate hazardous materials from inside the building to make it safe for visitors. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

The End of Wars As the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great

Naval War College Review Volume 53 Article 3 Number 4 Autumn 2000 The ndE of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great Wars of the Twentieth Century Donald Kagan Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Kagan, Donald (2000) "The ndE of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great Wars of the Twentieth Century," Naval War College Review: Vol. 53 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol53/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kagan: The End of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Gr Dr. Donald Kagan is Hillhouse Professor of History and Classics at Yale University. Professor Kagan earned a B.A. in history at Brooklyn College, an M.A. in classics from Brown University, and a Ph.D. in history from Ohio State University; he has been teaching history and classics for over forty years, at Yale since 1969. Professor Kagan has received honorary doctorates of humane let- ters from the University of New Haven and Adelphi University, as well as numerous awards and fellow- ships. He has published many books and articles, in- cluding On the Origins of War and the Preservation of Peace (1995), The Heritage of World Civilizations (1999), The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (1969), “Human Rights, Moralism, and Foreign Pol- icy” (1982), “World War I, World War II, World War III” (1987), “Why Western History Matters” (1994), and “Our Interest and Our Honor” (1997). -

Shemyaafr,Alaska 1992IRPFIELD INVESTIGATIONREPORT

EM0-1096 VOL 1 ShemyaAFR,Alaska 1992IRPFIELD INVESTIGATIOREPN ORT Volume 1 of 4 TECHNICAL .., FINAL February1993 preparedfor U.S.Air Force IO ElmendorfAFB,Alaska 11th AirControlWing 1lth CivilEngineeringOperationsSquadron UnderContractDEU-91-06 Preparedby CH2MHILL RC.Box8748 Boise,Idaho83707 For EnvironmentalManagementOperations Undera RelatedServicesAgreement withtheU.S.Departmentof Energy EnvironmentalManagementOperations Richland,Washington99352 j OtSTR|BUTIOPJ 0_:: ii-tIU L_OCuiviENT iL, ',..;;'-,_;;;.,.';,:{:1;" ,. FINAL I i i NOTICE i This report has been prepared for the United States Air Force by CH2M HILL for the purpose of aiding in the implementation of a final remedial action plan under the Air Force Installation Restoration Program (IRP). As the report relates to actual or possible releases of potentially hazardous substances, its release prior to an Air Force final decision on remedial action may be in the public's interest. The limited objectives of this report and the ongoing nature of the IRP, along with the evolving knowledge of site conditions and chemical effects on the environment and health, must be considered when evaluating this report, since subsequent facts may become known which may make this report premature or inaccurate. Acceptance of this report in performance of the contract under which it is prepared does not mean that the Air Force adopts the conclusions, recommendations or other views expressed herein, which are those of the contractor only and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the United States Air Force. Government agencies and their contractors registered with the Defense TechnicalInformationCenter (DTIC) should direct requestsfop copies of.this report to: Defense Technical InformationCenter (DTIC), Cameron Station,Alexandria, VA 22304-6145. -

The Stocked Lakes of Donnelly Training Area Getting There

The Stocked Lakes of Donnelly Training Area Getting There... The Alaska Department of Fish and Game stocks About 8 miles south of Delta Junction, at MP 257.6 has no road access, but it can be reached by 16 lakes on Donnelly Training Area. Depending on Fishing Tips Richardson Highway, Meadows Road provides floatplane in the summer. During winter, you can the lake, you can fish for rainbow trout, Arctic char, access to most of the Donnelly Training Area reach Koole Lake on the winter trail. Cross the Arctic grayling, landlocked salmon, and lake trout. In some of the deeper lakes, there are naturally stocked lakes. Bullwinkle, Sheefish, Bolio, Luke, Tanana River and follow the trail, which starts at MP occurring populations of lake chub, sculpin, Arctic Mark, North Twin, South Twin, No Mercy, 306.2 Richardson Highway near Birch Lake. Koole Anglers fish from the bank on most of these lakes grayling, and longnose sucker. Of the hundreds of Rockhound, and Doc lakes all lie within a few miles Lake is stocked with rainbow trout. ADF&G has a because there is fairly deep water near shore. accessible lakes that exist on Donnelly Training Area, of Meadows Road. trail map to Koole Lake. Contact us at 459-7228 to Inflatable rafts, float tubes, and canoes can also be only these 16 are deep enough to stock game fishes. obtain a map. used, but the lakes are too small for motorized You can use a variety of tackle to catch these stocked boats, and there are no launch facilities. fish.