Reclaiming Peace in International Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The End of Wars As the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great

Naval War College Review Volume 53 Article 3 Number 4 Autumn 2000 The ndE of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great Wars of the Twentieth Century Donald Kagan Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Kagan, Donald (2000) "The ndE of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great Wars of the Twentieth Century," Naval War College Review: Vol. 53 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol53/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kagan: The End of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Gr Dr. Donald Kagan is Hillhouse Professor of History and Classics at Yale University. Professor Kagan earned a B.A. in history at Brooklyn College, an M.A. in classics from Brown University, and a Ph.D. in history from Ohio State University; he has been teaching history and classics for over forty years, at Yale since 1969. Professor Kagan has received honorary doctorates of humane let- ters from the University of New Haven and Adelphi University, as well as numerous awards and fellow- ships. He has published many books and articles, in- cluding On the Origins of War and the Preservation of Peace (1995), The Heritage of World Civilizations (1999), The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (1969), “Human Rights, Moralism, and Foreign Pol- icy” (1982), “World War I, World War II, World War III” (1987), “Why Western History Matters” (1994), and “Our Interest and Our Honor” (1997). -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School REMEMBERING JIMMY CARTER THE RHETORICAL EVOCATIONS OF PRESIDENTIAL MEMORIES A Thesis in Communication Arts and Sciences by Brandon M. Johnson 2020 Brandon M. Johnson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2020 The thesis of Brandon M. Johnson was reviewed and approved by the following: Mary E. Stuckey Professor, Communication Arts and Sciences Thesis Advisor Stephen H. Browne Liberal Arts Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Michael J. Steudeman Assistant Professor of Rhetoric and Director of CAS100A Denise H. Solomon Head and Liberal Arts Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences iii ABSTRACT This thesis is an analysis of the public memory of Jimmy Carter and the way the historical resources of his presidency (including his perceived moral character) are interpreted and evoked as a shorthand for presidential failure by associating him with a rhetoric of weakness. Broadly, I consider the nature of presidential memory, asking how a presidency passes from history to memory. I suggest that presidential histories serve as inventional resources in the present, with rhetors evoking interpretations of the past as rhetorical appeals. These appeals are acts of memory, and analyzing how they function discursively and are deployed strategically draws out how presidential memory works and what implications it has to presidential rhetoric. The different strategies used in remembering the presidency of Jimmy Carter are useful texts for rhetorically critiquing this process because Carter is often deployed as a rhetorical shorthand, providing a representative example of interpreting presidential pasts. I begin by considering the evolving scholarship and historiography on Carter and conceptualizing how presidential pasts can be interpreted in the present through acts of remembering. -

The Art of the Deal for North Korea: the Unexplored Parallel Between Bush and Trump Foreign Policy*

International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Vol. 26, No. 1, 2017, 53–86. The Art of the Deal for North Korea: The Unexplored Parallel between Bush and Trump Foreign Policy* Soohoon Lee ‘Make America Great Again,’ has been revived while ‘America First’ and ‘peace through strength,’ have been revitalized by the Trump admin istration. Americans and the rest of the world were shocked by the dramatic transformation in U.S. foreign policy. In the midst of striking changes, this research analyzes the first hundred days of the Trump administration’s foreign policy and aims to forecast its prospects for North Korea. In doing so, the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy creeds, ‘American exceptionalism’ and ‘peace through strength,’ are revisited and compared with that of Trump’s. Beyond the similarities and differences found between the two administrations, the major finding of the analysis is that Trump’s profitoriented nature, through which he operated the Trump Organization for nearly a half century, has indeed influenced the interest- oriented nature in his operating of U.S. foreign policy. The prospects for Trump’s policies on North Korea will be examined through a business sensitive lens. Keywords: Donald Trump, U.S Foreign Policy, North Korea, America First, Peace through Strength Introduction “We are so proud of our military. It was another successful event… If you look at what’s happened over the eight weeks and compare that to what’s happened over the last eight years, you'll see there’s a tremen * This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF2016S1A3A2924968). -

THE UNITED STATES INSTITUTE of PEACE Sreeram Chaulia

International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 14, Number 1, Spring/Summer 2009 ONE STEP FORWARD, TWO STEPS BACKWARD: THE UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE Sreeram Chaulia Abstract This essay applies critical theories of knowledge-producing institutions to demonstrate the utility of a conceptual framework about elite institutions that are deployed by powerful authorities to suppress anti- establishment knowledge. It asserts that knowledge-centric institutions which are appendages of power structures act to consume radical grassroots ideas in society and replace them with sympathy, loyalty and obedience to the establishment. It uses the case of the United States Institute of Peace to test the framework and show how this think tank has been consistently used by US foreign policy elites as an instrument to counter the peace movement. The conclusion offers thoughts on structural conditions through which more objective and people-centric think tanks can be built. Knowledge-Producing Institutions and Hegemony Hegemonic power structures, be they domestic or international, rest on a tissue of ideas that is beefed up with economic and military muscle. Rationality dictates that powerful actors in a society or international system cannot permanently rely on coercion to achieve their ends. This is due to the impossibility of policing each nook and cranny of the space that is subject to rule, as well as the natural instinct of the weak to attempt “everyday forms of resistance” (Scott, 1985). No system of rule can completely avoid slippage and subversion at the margins, but it can employ a vast intellectual apparatus to ensure that dissenting knowledge is contained at manageable levels or quarantined, so that the whole forest does not catch flame. -

1 the Great Communicator and the Beginning of the End of the Cold War1 by Ambassador Eric S. Edelman President Ronald Reagan Is

The Great Communicator and the Beginning of the End of the Cold War1 By Ambassador Eric S. Edelman President Ronald Reagan is known as the “Great Communicator,” a soubriquet that was awarded to him by New York Times columnist Russell Baker, and which stuck despite Reagan’s disclaimer in his farewell address that he “wasn’t a great communicator” but that he had “communicated great things.” The ideas which animated Reagan’s vision were given voice in a series of extraordinary speeches, many of them justly renowned. Among them are his “Time for Choosing” speech in 1964, his “Shining City on a Hill” speech to CPAC in 1974, his spontaneous remarks at the conclusion of the Republican National Convention in 1976 and, of course, his memorable speeches as President of the United States. These include his “Evil Empire” speech to the National Association of Evangelicals, his remarks at Westminster in 1982, his elegiac comments commemorating the 40th anniversary of the D-Day invasion and mourning the Challenger disaster, and his Berlin speech exhorting Mikhail Gorbachev to “Tear Down this Wall” in 1987, which Time Magazine suggested was one of the 10 greatest speeches of all time.2 Curiously, Reagan’s address to the students of Moscow State University during the 1988 Summit with Mikhail Gorbachev draws considerably less attention today despite the fact that even normally harsh Reagan critics hailed the speech at the time and have continued to cite it subsequently. The New York Times, for instance, described the speech as “Reagan’s finest oratorical hour” and Princeton’s liberal historian Sean Wilentz has called it “the symbolic high point of Reagan’s visit…. -

Fighting Back Against the Cold War: the American Committee on East-West Accord And

Fighting Back Against the Cold War: The American Committee on East-West Accord and the Retreat from Détente A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Benjamin F.C. Wallace May 2013 © 2013 Benjamin F.C. Wallace. All Rights Reserved 2 This thesis titled Fighting Back Against the Cold War: The American Committee on East-West Accord and the Retreat from Détente by BENJAMIN F.C. WALLACE has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Chester J. Pach Associate Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT WALLACE, BENJAMIN F.C., M.A., May 2013, History Fighting Back Against the Cold War: The American Committee on East-West Accord and the Retreat From Détente Director of Thesis: Chester J. Pach This work traces the history of the American Committee on East-West Accord and its efforts to promote policies of reduced tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s. This organization of elite Americans attempted to demonstrate that there was support for policies of U.S.-Soviet accommodation and sought to discredit its opponents, especially the Committee on the Present Danger. This work argues that the Committee, although largely failing to achieve its goals, illustrates the wide-reaching nature of the debate on U.S.-Soviet relations during this period, and also demonstrates the enduring elements of the U.S.-Soviet détente of the early 1970s. -

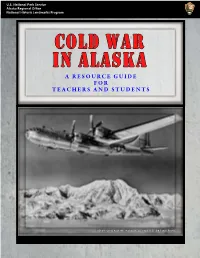

Cold War in Alaska a Resource Guide for Teachers and Students

U.S. National Park Service Alaska Regional Office National Historic Landmarks Program COLD WAR IN ALASKA A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS RB-29 flying past Mt. McKinley, ca. 1948, U.S. Air Force Photo. DANGER Colors, this page left, mirror those used in the first radiation symbol designed by Cyrill Orly in 1945. The three-winged icon with center dot is "Roman violet,"a color used by early Nuclear scientists to denote a very precious item. The "sky blue" background was intended to create an arresting contrast. Original symbol (hand painted on wood) at the Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Radiation_symbol_-_James_V._For- restal_Building_-_IMG_2066.JPG ACTIVE U.S. Army soldiers on skis, Big Delta, Alaska, April 9, 1952, P175-163 Alaska State Library U.S. Army Signal Corps Photo Collection. U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Alaska Regional Office National Historic Landmarks Program First Printing 2014 Introduction Alaska’s frontline role during the Cold War ushered in unprecedented economic, technological, political, and social changes. The state’s strategic value in defending our nation also played a key role in its bid for statehood. Since the end of the Cold War, Alaska’s role and its effects on the state have received increasing focus from historians, veterans, and longtime Alaskans. This resource guide is designed to help students and teachers in researching the Cold War in Alaska, and to provide basic information for anyone who is interested in learning more about this unique history. The guide begins with a map of Cold War military sites in Alaska and a brief summary to help orient the reader. -

President Ronald Reagan

President Ronald Reagan In the 1950s, Ronald Reagan turned to television. From 1954 to 1962 he was the host of General Electric Theater, a weekly program with a national audience. Later, he appeared in Death Valley Days, a dramatic series about the western frontier in American history. He also became intensely interested in politics, accepting many invitations to make speeches about political issues and policies. Ronald Reagan’s turn to political activity had begun several years earlier, when he was president of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) from 1947 to 1952. He served a final term as SAG president from 1959 to 1960. The Hollywood community during those years was filled with political controversy caused by the worldwide conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. It was called the Cold War because the opponents rarely directly engaged in battle. Ronald Reagan was concerned that some people involved in moviemaking sympathized with the Soviet Union’s goal of spreading its communist system of government throughout the world, which the United States opposed. He feared that lofty Soviet claims about government-controlled advancement of social justice “had fooled some otherwise loyal Americans into believing that the Communist Party sought to make a better world.” As president of SAG, Ronald Reagan opposed what he saw as communist influence among the moviemakers. He pointed out that Soviet communism was a totalitarian system in which individual liberty was totally denied and dissent was brutally crushed. He explained, “On the one hand is our belief that the people can and will decide what is best for themselves, and on the other (communist, Nazi, or fascist) side is the belief that a ‘few’ can best decide what is good for all the rest.” While leading SAG, Ronald Reagan forged his fervent anticommunism and abiding commitment to traditional American principles of constitutional and representative government, individual liberty, and the rule of law. -

Topical Essays

Topical Essays Supplying the Manpower That America’s National Security Strategy Demands Blaise Misztal and Jack Rametta1 Introduction time to introduce new and beneficial regula- The first mention of the military in our na- tions, and to expunge all customs, which from tion’s founding document refers, perhaps not experience have been found unproductive of surprisingly, to the authority, vested in Con- general good.”3 The questions that Washington gress, to create an armed force in the first place. raises go beyond concerns about an incipient Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution imbues armed force and are critical to the strength of the legislative branch with the power to “raise any military, but particularly one that depends, and support Armies.” However, the Constitu- as the U.S. military does, on voluntary service. tion provides little guidance as to what else Indeed, one could argue that the unrivaled Congress should take into account in raising superiority of the American armed forces over an Army. the past 70 years can be attributed in large part Fortunately, George Washington, soon to to the willingness of lawmakers and defense be our first commander in chief, laid out his leaders to revisit and revise how servicemem- vision for the U.S. military. Washington’s “Sen- bers are recruited, managed, promoted, paid, timents on a Peace Establishment,” written in and retained. The set of laws and policies that 1783 three years before he assumed the presi- manage these functions, known collective- dency, might be the first treatise on -

The Abraham Accords: Paradigm Shift Or Realpolitik? by Tova Norlen and Tamir Sinai

The Abraham Accords: Paradigm Shift or Realpolitik? By Tova Norlen and Tamir Sinai Executive Summary This paper analyzes the motives and calculations of Israel, the United States, and the United Arab Emirates— the signatories of the Abraham Accords—which were signed on the White House Lawn on September 15, 2020. The Accords normalize relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Israel and Bahrain. The agreements signed by Israel with two Gulf States symbolizes a major shift in Middle Eastern geopolitics, which have long been characterized by the refusal of Arab Gulf states to engage in talks with Israel. However, the possible larger consequences of the agreement cannot be fully understood without considering the complex set of domestic and foreign policy causes that prompted the parties to come to the negotiating table. By signing the agreement, Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu was able to avoid the controversial West Bank annexation plan, which, if executed, could prove disastrous for him both at home and abroad. On the other hand, the UAE, while officially claiming credit for preventing the annexation, is now able to establish full diplomatic relations with Israel, with great advantages both to its economy and military security. For the Trump administration, the Abraham Accord represents the President’s first real foreign policy achievement, a victory especially welcome so close to the U.S. elections. This will be popular with the president’s conservative, pro-Israel base, and an achievement that Democrats, Biden in particular, will have difficulties critiquing. Geopolitically, the deal strengthens the informal anti-Iran alliance in the region, increasing pressure on Tehran and strengthening U.S. -

Ownload Economic Battle Plan

LT. COl. Allen West - Global & Domestic Threats 2.51 [Economic Battle PlanTM points: 75] Background Briefing: With the 2020 election coming up, America is at a critical crossroad. Lt. Col Allen West visits the Economic War Room to provide an update regarding external and internal threats facing America. Also, Col. West makes a major announcement about his plans to help America and Texas. WARNING: China and Iran may have more interest in what happens to the US election in 2020 than the average voter. This briefing highlights what you should be sharing with your friends and associates now. Your Mission: To better understand the key internal and external threats facing America, the motivations behind them, and why with this upcoming election your vote is more important than ever! page 1 LT. COl. Allen West - Global & Domestic Threats 2.51 [Economic Battle PlanTM points: 75] (OSINT)– Open Sourced Intelligence Briefing Open Sourced Intelligence Briefing with highlights. This includes quotes and summaries of conversations in the Economic War Room with Kevin Freeman and Lt. Col. Allen West. 1. The Importance of American Sovereignty and Peace Through Strength: • We want to have a credible military deterrent We do not want more wars, but our adversaries need to believe that we will confront and engage them when it is needed. • The successful strategy of “Peace through Strength” is very different than Obama’s approach of “Strategic Patience.” The patience strategy led to the rise of ISIS and the enablement of Iran. • With the Trump administration, we went from a weak presence to a strong presence globally. -

Eisenhower-Kennedy Foreign

Dwight D. Eisenhower John F. Kennedy Foreign Policy Relations with the Soviet Union • Hungary rebellion (1956) • Soviets crush it Impact of John Foster Dulles • Secretary of State • Replace “containment” with “rollback” – “push back” to pre-WWII levels • Weapons – Less for conventional – More for nuclear – “Massive retaliation”/Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) • Use of CIA • Peace through strength • Arms race Alliances – more Collective Security • U.S., South Korea, Taiwan • Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) – U.S., Australia, Pakistan, Thailand, New Zealand, Philippines, South Vietnam • Allied with more “S.O.B.’s” – Philippines, Cuba, Nicaragua, Iran, Dominican Republic Role of CIA • Allen Dulles (John Foster’s brother) • Help overthrow communist leaning governments – Prime Minister of Iran in favor of Shah (oil) – Arbenz in Nicaragua (fruit) – Sukarno in Indonesia (failed) – Castro in Cuba (failed) Issues in the Middle East • Main concern in the Middle East: oil • Other issue: Israeli statehood Issues in the Middle East • British controlled Palestine • U.N. created Israel and Palestine • Jerusalem under U.N. control • WARS – 1947: Israeli Statehood • U.S. supports Israel – 1956: Suez Crisis • U.S. supports Egypt • Eisenhower Doctrine – Assist any Middle Eastern nation attempting to stop communist aggression – Involved in Jordan and Lebanon Issues in the Middle East Impact of the Cold War • Nuclear testing and impact • http://www.youtube.com/watc h?v=JRS4CrFdXOk • How to protect yourself • http://www.youtube.com/watc h?v=11EWuW_aWCI