Downloading of Music and Playing Online Video Games (Featherstone 2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

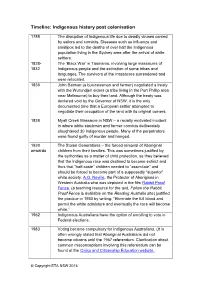

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace Oral Tradition 1/2 (1986): 231-71 Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions Margaret Clunies Ross 1. Aboriginal Oral Traditions A History of Research and Scholarship1 The makers of Australian songs, or of the combined songs and dances, are the poets, or bards, of the tribes, and are held in great esteem. Their names are known in the neighboring tribes, and their songs are carried from tribe to tribe, until the very meaning of the words is lost, as well as the original source of the song. It is hard to say how far and how long such a song may travel in the course of time over the Australian continent. (Howitt 1904:414) In 1988 non-Aboriginal Australians will celebrate two hundred years’ occupation of a country which had previously been home to an Aboriginal population of about 300,000 people. They probably spoke more than two hundred different languages and most individuals were multilingual (Dixon 1980). They had a rich culture, whose traditions were centrally concerned with the celebration of three basic types of religious ritual-rites of fertility, initiation, and death (Maddock 1982:105-57). In many parts of Australia, particularly in the south where white settlement was earliest and densest, Aboriginal traditional life has largely disappeared, although the memory of it has been passed down the generations. Nowadays all Aborigines, even in the most traditional parts of the north, such as Arnhem Land, are affected to a greater or lesser extent by the Australian version of Western culture, and must preserve their own traditions by a combination of holding strategies. -

Raising Awareness of Australian Aboriginal Peoples Reality: Embedding Aboriginal Knowledge in Social Work Education Through the Use of Field Experiences

The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 2013, 12(1), 197–212 iSSN 1443-1475 © 2013 www.iejcomparative.org Raising awareness of Australian Aboriginal peoples reality: Embedding Aboriginal knowledge in social work education through the use of field experiences Deb Duthie Queensland University of Technology, Australia Julie King Queensland University of Technology, Australia Jenni Mays Queensland University of Technology, Australia Effective social work practice with Aboriginal peoples and communities requires knowledge of operational communication skills and practice methods. In addition, there is also a need for practitioners to be aware of the history surrounding white engagement with Aboriginal communities and their cultures. Indeed, the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) acknowledges the importance of social workers practising cultural safety. Engendering knowledge of cultural safety for social work students is the opportunity to listen and talk with Aboriginal people who have experienced the destructive impacts of colonisation and the subsequent disruption to family and community. This article discusses the use of field experiences within a Masters of Social Work (Qualifying) Program (MSW) as an educational method aimed at increasing student awareness of contemporary Aboriginal issues and how to practice effectively and within a culturally safe manner. KeyWords: Aboriginal Australia, social work education, cultural safety, field experiences, blended learning. Australia was colonised by Great Britain in the late 18th Century. From the outset, the impact on Aboriginal peoples was detrimental on many levels. As has been well documented, this impact has taken many forms, from semi-official extermination (Lake & Reynolds, 2008; Richards, 2008) through to social engineering policies of less 197 Raising awareness of Australian Aboriginal peoples reality obvious brutality. -

2.5: a Journey Towards Adolescence and an Aboriginal Dance Method

2.5: A Journey towards Adolescence and an Aboriginal Dance Method Michael Leslie A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts University of New South Wales Art and Design December 2016 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Leslie First name: Michael Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Master of Fine Arts School: Paddington Campus Faculty: Art & Design Title: 2.5: A Journey towards Adolescence and an Aboriginal Dance Method Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This project records my history as an Aboriginal dancer who trainedboth in Australia and the USA. The end result of this history is a new Aboriginal Dance Method, which seeks a synthesis with African American dance, and other contemporary dance fonns. In describing This new fonn, is informed by Gamilaraay Language, culture, mammals, birds, reptiles, qualities, elements, moving, parts ofthe body, material culture, water, doing, places, times,and questions. The dance sequence will include contemporary techno music and theatreto synthesise and to explore this new dance typology via the use of 100 steps drawn fromthe Gamilaraay language. These 100 steps are the core creation ofthis Masters. Is it possible to synthesise into another essentially "Aboriginal Dance Method" modern European ballet, physical theatre,African American dance and both ancient and modernAboriginal dance types? The urban Aborigine is oftendivorced, like myself, fromtraditional initiation ceremony and hence cultural Rights of Passage. Loss ofritual and ceremony coupled with racism and no safeplace to exist in society, has generated a mark milestone of institutionalism or goal time as a mark of being a man. -

American Misconceptions About Australian Aboriginal Art

AMERICAN MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Gina Cirino August 2015 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Gina Cirino B.A., Ohio University, 2000 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ___________________________________ Richard Feinberg, Ph.D., Department of Anthropology, Masters Advisor ___________________________________ Richard S. Meindl, Ph.D., Chair, Department of Anthropology _____________________________________ James L. Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS.……………………………………………………………………..….iv LIST OF FIGURES.……………………………………………………………………………..vii LIST OF TABLES..…………………………………………………………………………….viii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..………………………………………..………………………....…..ix CHAPTER I. RELEVANCE OF THIS STUDY………………………………………………………...1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..1 Objectives of thesis……………………………………………………………………..…2 Contents of thesis…………………………………………………………………...……..4 Persecution of Aboriginal groups……………………………………………………...….5 Deception of the Australian Government…………………………………………7 Systemic discrimination and structural Violence………………………………....9 Correlations between poverty and health………………………………………...13 Human Development Index (HDI)………………………………………………………14 Growing responsibilities of anthropologists……………………………………………..17 II. OVERVIEW OF ABORIGINAL ART …………………………………………………20 Artworld Definitions……………………………………………………………………..20 The development -

The Perils of Identifying As Indigenous on Social Media

genealogy Article Us Mob Online: The Perils of Identifying as Indigenous on Social Media Bronwyn Carlson * and Tristan Kennedy Department of Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Social media is a highly valuable site for Indigenous people to express their identities and to engage with other Indigenous people, events, conversations, and debates. While the role of social media for Indigenous peoples is highly valued for public articulations of identity, it is not without peril. Drawing on the authors’ recent mixed-methods research in Australian Indigenous communities, this paper presents an insight into Indigenous peoples’ experiences of cultivating individual and collective identities on social media platforms. The findings suggest that Indigenous peoples are well aware of the intricacies of navigating a digital environment that exhibits persistent colonial attempts at the subjugation of Indigenous identities. We conclude that, while social media remains perilous, Indigenous people are harnessing online platforms for their own ends, for the reinforcement of selfhood, for identifying and being identified and, as a vehicle for humour and subversion. Keywords: Aboriginal; Indigenous; social media; identity; hate speech; community; online 1. Introduction Citation: Carlson, Bronwyn, and For as long as social media platforms have existed, the topic of Indigenous identity Tristan Kennedy. 2021. Us Mob has featured in online conversations and debates. Research reveals that for Indigenous Online: The Perils of Identifying as people, identifying as Indigenous online is a risky business where you are likely to be Indigenous on Social Media. subjected to extreme hate and racism (see, Carlson 2016; Carlson and Frazer 2018a, 2018b; Genealogy 5: 52. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

1 Bibliography for Ancestral Modern: Australian

Bibliography for Ancestral Modern: Australian Aboriginal Art from the Kaplan & Levi Collection Prepared by Traci Timmons, SAM Librarian Resources for Adults: The Dorothy Stimson Bullitt Library Books and videos are available in the Bullitt Library (Seattle Art Museum, Fifth Floor, South Building). 1. EXHIBITION CATALOGUE: Ancestral Modern: Australian Aboriginal Art: Kaplan & Levi Collection. Pamela McClusky et al. Seattle: New Haven; London: Seattle Art Museum; Yale University Press, 2012. N 7401 M33 A73. 2. Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art: Collection Highlights from the National Gallery of Australia. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: National Gallery of Australia, 2010. N 7401 C27 2010. 3. Aboriginal Art. Wally Caruana. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1993. DCT N 7401 C2. 4. Aboriginal Art. Howard Morphy. London: Phaidon, 1998. N 7401 M67. 5. Aboriginal Art Papers. Pamela Z. McClusky et al. Various Publishers, 2005. DCT N 7400 M33. This is a gathering of a number of articles on Australian Aboriginal art gathered by SAM Docents. 6. Aboriginal Artists of the Western Desert: A Biographical Dictionary. Vivien Johnson. Roseville East, NSW: Craftsman House: Distributed by Craftsman house in association with G+B Arts, 1994.N 7401 J65. 7. Aboriginal Title and Indigenous Peoples: Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Louis A. Knafla and Haijo Jan Westra. Vancouver: UBC Press, c2010. K 3248 L36 A93. 8. Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal System of Knowledge. Howard Morphy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. DU 125 M67 A6. 9. Art + Soul: A Journey into the World of Aboriginal Art. Hetti Perkins. Carlton, Victoria: Miegunyah Press, 2010. N 7401 P37. 10. Art + Soul: A Journey into the World of Aboriginal Art (video). -

Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy the Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing

9 No. Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy The Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Vicki Grieves Discussion Paper Series: Discussion Paper Aboriginal Spirituality provides a philosophical baseline for Indigenous knowledges development in Australia. It is Aboriginal knowledges that build the capacity to enhance the social and emotional wellbeing for Aboriginal people now living within a colonial regime. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health Discussion Paper Series: No. 9 Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy The Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Vicki Grieves © Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009 CRCAH Discussion Paper Series – ISSN 1834–156X ISBN 978–0–7340–4102–9 First printed in December 2009 This work has been published as part of the activities of the Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health (CRCAH). The CRCAH is a collaborative partnership partly funded by the Cooperative Research Centre Program of the Australian Government Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, or by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community organisations subject to an acknowledgment of the source and no commercial use or sale. Reproduction for other purposes or by other organisations requires the written permission of the copyright holder(s). Additional copies of this publication (including a pdf version on the CRCAH website) can be obtained from: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health PO Box 41096, Casuarina NT 0811 AUSTRALIA T: +61 8 8943 5000 F: +61 8 8943 5010 E: [email protected] W: www.crcah.org.au Authors: Vicki Grieves Managing Editor: Jane Yule Copy Editor: Cathy Edmonds Cover photograph: Photograph of Alfred Coolwell by Vicki Grieves Original Design: Artifishal Studios Formatting and Printing: InPrint Design For citation: Grieves, V.