Recent Changes to the Indigenous Population Geography of Australia: Evidence from the 2016 Census

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

Torresstrait Islander Peoples' Connectiontosea Country

it Islander P es Stra eoples’ C Torr onnec tion to Sea Country Formation and history of Intersection of the Torres Strait the Torres Strait Islands and the Great Barrier Reef The Torres Strait lies north of the tip of Cape York, Torres Strait Islanders have a wealth of knowledge of the marine landscape, and the animals which inhabit it. forming the northern most part of Queensland. Different marine life, such as turtles and dugong, were hunted throughout the Torres Strait in the shallow waters. Eighteen islands, together with two remote mainland They harvest fish from fish traps built on the fringing reefs, and inhabitants of these islands also embark on long towns, Bamaga and Seisia, make up the main Torres sea voyages to the eastern Cape York Peninsula. Although the Torres Strait is located outside the boundary of the Strait Islander communities, and Torres Strait Islanders Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, it is here north-east of Murray Island, where the Great Barrier Reef begins. also live throughout mainland Australia. Food from the sea is still a valuable part of the economy, culture and diet of Torres Strait Islander people who have The Torres Strait Islands were formed when the land among the highest consumption of seafood in the world. Today, technology has changed, but the cultural use of bridge between Australia and Papua New Guinea the Great Barrier Reef by Torres Strait Islanders remains. Oral and visual traditional histories link the past and the was flooded by rising seas about 8000 years ago. present and help maintain a living culture. -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

The Boomerang Effect. the Aboriginal Arts of Australia 19 May - 7 January 2018 Preview 18 May 2017 at 6Pm

MEG Musée d’ethnographie de Genève Press 4 may 2017 The Boomerang Effect. The Aboriginal Arts of Australia 19 May - 7 January 2018 Preview 18 May 2017 at 6pm White walls, neon writing, clean lines: the MEG’s new exhibition «The Boomerang Effect. The Aboriginal Arts of Australia» welcomes its visitors in a space evocative of a contemporary art gallery. Here the MEG unveils one of its finest collections and reveals the wealth of indigenous Australia's cultural heritage. Visiting this exhibition, we understand how attempts to suppress Aboriginal culture since the 18th century have ended up having the opposite of their desired effect. When James Cook landed in Australia, in 1770, he declared the country to be «no one’s land» (terra nullius), as he recognized no state authority there. This justified the island's colonization and the limitless spoliation of its inhabitants, a medley of peoples who had lived there for 60,000 years, societies which up until today have maintained a visible and invisible link with the land through a vision of the world known as the Dreaming or Dreamtime. These mythological tales recount the creation of the universe as well as the balanced and harmonious relation between all the beings inhabiting it. It is told that, in ancestral times, the Djan’kawu sisters peopled the land by naming the beings and places and then lying down near the roots of a pandanus tree to give birth to sacred objects. It is related that the Dätiwuy clan and its land was made by a shark called Mäna. -

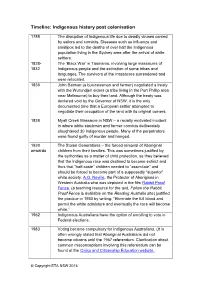

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

Torres Strait Islanders: a New Deal

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS: A NEW DEAL A REPORT ON GREATER AUTONOMY FOR TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Affairs August 1997 Canberra Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISBN This document was produced from camera-ready copy prepared by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs and printed by AGPS Canberra. The cover was produced in the AGPS design studios. The graphic on the cover was developed from a photograph taken on Yorke/Masig Island during the Committee's visit in October 1996. CONTENTS FOREWORD ix TERMS OF REFERENCE xii MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE xiii GLOSSARY xiv SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS xv CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE.......................................................................................................................................1 CONDUCT OF THE INQUIRY ......................................................................................................................................1 SCOPE OF THE REPORT.............................................................................................................................................2 PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS .................................................................................................................................3 Commonwealth-State Cooperation ....................................................................................................................3 -

Recent Changes to the Indigenous Population Geography of Australia: Evidence from the 2016 Census

AUSTRALIAN POPULATION STUDIES 2018 | Volume 2 | Issue 1 | pages 1–13 Recent changes to the Indigenous population geography of Australia: evidence from the 2016 Census Francis Markham* The Australian National University Nicholas Biddle The Australian National University * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]. Address: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University, 24 Kingsley Street, Acton, ACT 2601, Australia Paper received 15 February 2018; accepted 3 May 2018; published 28 May 2018 Abstract Background The Indigenous population of Australia has grown very rapidly since the first tabulation of census statistics about Indigenous people in the 1971 ABS Census of Population and Housing (Census). Understanding the size and location of the Indigenous Australians is important to the State for service delivery and policy, and for Indigenous peoples themselves. Aims This paper summarises changes to population geography of Indigenous Australians between 2011 and 2016. It describes the growth in the estimated population, and its changing geographic distribution. The paper derives a measure of ‘unexpected population change’: the spatial mismatch between demographic projections from the 2011 and 2016 Census counts. Data and methods Census data and population projections are tabulated and mapped. Results Indigenous people now comprise 3.3 per cent of the total Australian population, or 798,381 persons. This population grew by 3.5 per cent each year between 2011 and 2016, a rate of growth 34 per cent faster than that explained by natural increase alone. Both aspects of growth were concentrated in more urban parts of the country, especially coastal New South Wales and southeast Queensland. -

The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: an Overview (Full Publication; 5 May

The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people an overview 2011 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare is Australia’s national health and welfare statistics and information agency. The Institute’s mission is better information and statistics for better health and wellbeing. © Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Head of the Communications, Media and Marketing Unit, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, GPO Box 570, Canberra ACT 2601. A complete list of the Institute’s publications is available from the Institute’s website <www.aihw.gov.au>. ISBN 978 1 74249 148 6 Suggested citation Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2011. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, an overview 2011. Cat. no. IHW 42. Canberra: AIHW. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Board Chair Hon. Peter Collins, AM, QC Director David Kalisch Any enquiries about or comments on this publication should be directed to: Communication, Media and Marketing Unit Australian Institute of Health and Welfare GPO Box 570 Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: (02) 6244 1032 Email: [email protected] Published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Printed by Paragon Printers Australasia Please note that there is the potential for minor revisions of data in this report. Please check the online version at <www.aihw.gov.au> for any amendments. -

Trauma in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population

Australian Clinical Psychologist Volume 3 Issue 1 Article no. 004 ISSN 2204-4981 Trauma in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population Pat Dudgeon School of Indigenous Studies, University of Western Australia Marshall Watson Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, SA Health and Christopher Holland Private Consultant Abstract: The prevalence of trauma is beginning to be recognised as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population health issue. Trauma in this context needs to be understood in a way that accounts for the experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Furthermore, the impact and contribution of trauma to many other problems in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is only starting to be acknowledged. Relevant types of trauma are those related to historical events with intergenerational and transgenerational impacts; trauma resulting from repeated exposure to life stressors; trauma resulting from specific, intense life experiences; and trauma arising from adverse childhood experiences including complex and developmental trauma. In clinical settings, this layering of trauma can present unique challenges to health and mental health professionals and workers. Community-level healing responses are also important. Trauma should be addressed as a significant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population health issue. Keywords: trauma, Indigenous, intergenerational, stressors, population health This paper examines untreated trauma among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, families and communities and some of the challenges faced by health and mental health professionals and workers in ensuring effective diagnosis and treatment. The discussion is informed by the work of the national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation that has leadership in ensuring the recognition of trauma as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population health issue. -

Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace Oral Tradition 1/2 (1986): 231-71 Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions Margaret Clunies Ross 1. Aboriginal Oral Traditions A History of Research and Scholarship1 The makers of Australian songs, or of the combined songs and dances, are the poets, or bards, of the tribes, and are held in great esteem. Their names are known in the neighboring tribes, and their songs are carried from tribe to tribe, until the very meaning of the words is lost, as well as the original source of the song. It is hard to say how far and how long such a song may travel in the course of time over the Australian continent. (Howitt 1904:414) In 1988 non-Aboriginal Australians will celebrate two hundred years’ occupation of a country which had previously been home to an Aboriginal population of about 300,000 people. They probably spoke more than two hundred different languages and most individuals were multilingual (Dixon 1980). They had a rich culture, whose traditions were centrally concerned with the celebration of three basic types of religious ritual-rites of fertility, initiation, and death (Maddock 1982:105-57). In many parts of Australia, particularly in the south where white settlement was earliest and densest, Aboriginal traditional life has largely disappeared, although the memory of it has been passed down the generations. Nowadays all Aborigines, even in the most traditional parts of the north, such as Arnhem Land, are affected to a greater or lesser extent by the Australian version of Western culture, and must preserve their own traditions by a combination of holding strategies. -

Raising Awareness of Australian Aboriginal Peoples Reality: Embedding Aboriginal Knowledge in Social Work Education Through the Use of Field Experiences

The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 2013, 12(1), 197–212 iSSN 1443-1475 © 2013 www.iejcomparative.org Raising awareness of Australian Aboriginal peoples reality: Embedding Aboriginal knowledge in social work education through the use of field experiences Deb Duthie Queensland University of Technology, Australia Julie King Queensland University of Technology, Australia Jenni Mays Queensland University of Technology, Australia Effective social work practice with Aboriginal peoples and communities requires knowledge of operational communication skills and practice methods. In addition, there is also a need for practitioners to be aware of the history surrounding white engagement with Aboriginal communities and their cultures. Indeed, the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) acknowledges the importance of social workers practising cultural safety. Engendering knowledge of cultural safety for social work students is the opportunity to listen and talk with Aboriginal people who have experienced the destructive impacts of colonisation and the subsequent disruption to family and community. This article discusses the use of field experiences within a Masters of Social Work (Qualifying) Program (MSW) as an educational method aimed at increasing student awareness of contemporary Aboriginal issues and how to practice effectively and within a culturally safe manner. KeyWords: Aboriginal Australia, social work education, cultural safety, field experiences, blended learning. Australia was colonised by Great Britain in the late 18th Century. From the outset, the impact on Aboriginal peoples was detrimental on many levels. As has been well documented, this impact has taken many forms, from semi-official extermination (Lake & Reynolds, 2008; Richards, 2008) through to social engineering policies of less 197 Raising awareness of Australian Aboriginal peoples reality obvious brutality.