Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memories of the Origins of Ethnographic Film / Beate Engelbrecht (Ed.)

Contents Preface Beate Engelbrecht IX Introduction 1 The Early Years of Visual Anthropology Paul Hockings 3 The Prehistory of Ethnographic Film Luc de Heusch 15 Precursors in the Documentary Film 23 Robert Flaherty as I Knew Him. R ichard L eacock 2 5 Richard Leacock and the Origins of Direct Cinema: Re-assessing the Idea of an 'Uncontrolled Cinema' Chris tof Decker 31 Grierson Versus Ethnographic Film Brian Winston 49 Research and Record-Making Approaches 57 Recording Social Interaction: Margaret Mead and Gregory Batcson's Contribution to Visual Anthropology in Ethnographic Context Gerald Sullivan 59 From Bushmen to Ju/'Hoansi: A Personal Reflection on the Early Films of John Marshall. Patsy Asch 71 Life By Myth: The Development of Ethnographic Filming in the Work of John Marshall John Bishop 87 Pulling Focus: Timothy Asch Between Filmmaking and Pedagogy Sarah Elder 95 VI Contents Observational and Participatory Approaches 121 Colin Young, Ethnographic Film and the Film Culture of the 1960s David MacDougall 1 23 Colin Young and Running Around With a Camera Judith MacDougall 133 The Origins of Observational Cinema: Conversations with Colin Young Paul Henley 139 Looking for an Indigenous View 163 The Worth/Adair Navajo Experiment - Unanticipated Results and Reactions Richard Chalfen 165 The Legacy of John Collier, Jr. Peter Biella 111 George Stoney: The Johnny Appelseed of Documentary Dorothy Todd Henaut 189 The American Way 205 "Let Me Tell You A Story": Edmund Carpenter as Forerunner in the Anthropology of Visual Media Harald Prins and John Bishop 207 Asen Balikci Films Nanook Paul Hockings 247 Robert Gardner: The Early Years Karl G. -

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

Corroboree Moderne

Corrected draft May 2004 CORROBOREE MODERNE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dressed in a brown wool bodystocking specially made by Jantzen and brown face paint, an American dancer, Beth Dean played the young boy initiate in the ballet CORROBOREE at a Gala performance before Queen Elizabeth 11 and Prince Phillip on Feb 4 1954 . “On stage she seems to exude some of the primitive passion of the savage whose rites she presents” (1a) “If appropriations do have a general character, it is surely that of unstable duality. In some proportion, they always combine taking and acknowledgment, appropriation and homage, a critique of colonial exclusions, and collusion in imbalanced exchange. What the problem demands is therefore not an endorsement or rejection of primitivism in principle, but an exploration of how particular works were motivated and assessed.” (1) CORROBOREE "announced its modernity as loudly as its Australian origins…all around the world" (2) 1: (BE ABORIGINAL !) (3) - DANCE A CORROBOREE! The 1950s in the Northern Territory represents simultaneously the high point of corroboree and its vanishing point. At the very moment one of the most significant cultural exchanges of the decade was registered in Australian Society at large, the term corroboree became increasingly so associated with kitsch and the inauthentic it was erased as a useful descriptor, only to be reclaimed almost fifty years later. Corroboree became the bastard notion par excellence imbued with “in- authenticity.” It was such a popularly known term, that it stood as a generic brand for anything dinky-di Australian. (4) Corroboree came to be read as code for tourist trash culture corrupted by white man influence. -

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

Antropología

Artes y Humanidades Guías para una docencia universitaria con perspectiva de género Antropología Jordi Roca Girona ESTA COLECCIÓN DE GUÍAS HA SIDO IMPULSADA POR EL GRUPO DE TRABAJO DE IGUALDAD DE GÉNERO DE LA RED VIVES DE UNIVERSIDADES Elena Villatoro Boan, presidenta de la Comisión de Igualdad y Conciliación de Vida Laboral y Familiar, Universitat Abat Oliba CEU. M. José Rodríguez Jaume, vicerrectora de Responsabilidad Social, Inclusión e Igualdad, Universitat d’Alacant. Cristina Yáñez de Aldecoa, coordinadora del Rectorado en Internacionalización y Relaciones Institucionales, Universitat d’Andorra. Maria Prats Ferret, directora del Observatorio para la Igualdad, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. M. Pilar Rivas Vallejo, directora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat de Barcelona. Ruth María Abril Stoffels, directora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat CEU Cardenal Herrera. Anna Maria Pla Boix, delegada del rector para la Igualdad de Género, Universitat de Girona. Esperanza Bosch Fiol, directora de la Oficina para la Igualdad de Oportunidades entre Mujeres y Hombres, Universitat de las Illes Balears. Consuelo León Llorente, directora del Observatorio de Políticas Familiares, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya. Mercedes Alcañiz Moscardó, directora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat Jaume I. Anna Romero Burillo, directora del Centro Dolors Piera de Igualdad de Oportunidades y Promoción de las Mujeres, Universitat de Lleida. María José Alarcón García, directora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat Miguel Hernández d’Elx. Maria Olivella Quintana, coordinadora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. Dominique Sistach, responsable de la Comisión de Igualdad de Oportunidades, Universitat de Perpinyà Via Domitia. Silvia Gómez Castán, técnica de Igualdad del Gabinete de Innovación y Comunidad, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

Mapping Landscapes of the Mind: a Cadastral Conundrum in the Native Title Era

Mapping landscapes of the mind: A cadastral conundrum in the Native Title era Graeme Neate President, National Native Title Tribunal Presented at the UN-FIG Conference on Land Tenure and Cadastral Infrastructures for Sustainable Development, Melbourne, Australia 25-27 October 1999 ABSTRACT When the Crown progressively assumed sovereignty over different parts of Australia, groups of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had their own laws and customs which made them traditional owners of different parts of the land. Despite more than two centuries of colonisation, traditional links to land have survived and are exercised in some places. Through the prism of their cultural heritage, traditional owners of the land see geological features and items of vegetation as instances of Dreamtime activity. The stories, the songs, the ceremonies and the language are embedded in the land but are maintained in the minds of successive generations of traditional owners. The features of the landscape can be observed by all, but their meaning and significance is known to the few. In that sense, the traditional estates of indigenous groups are landscapes of the mind. The legal recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights and interests in land, and laws providing for the recognition and protection of areas of particular significance to indigenous Australians, have generated the need to precisely describe the location and extent of indigenous interests in land. That requirement gives rise to numerous issues about how indigenous peoples’ rights are to be -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

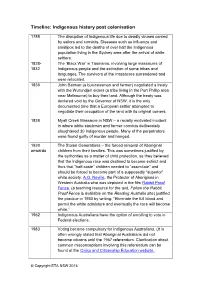

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

Cultural Heritage Strategy 2008

Cultural Heritage Strategy 2008 – 2011 Preserving and promoting our cultural heritage Before unveiling the plaque From MMBW to at the offi cial opening of the Upper Yarra Dam, the Governor Melbourne Water acknowledged the motto of the Metropolitan Board ‘Public health is my reward’ and added… “I think you will agree that our Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works has never let us down in the past. It certainly has not let us A motto is a phrase describing the motivation or intention of an organisation. The crest of the down today and I know it will MMBW bears the motto, ‘salas mea publica merces’ not let us down in the future.” (‘public health is my reward’). 1891 Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) was established with a charter to build and maintain an underground sewerage system and operate Melbourne’s water supply. 1991 MMBW merged with the Mornington Peninsula District Water Board, Dandenong Valley and Western Port Authorities, Dandenong- Springvale Water Board, Pakenham Water Board, Lang Lang Water Board and Emerald Water Board to form Melbourne Water. At this time, Melbourne Water has three operational regions – Maribyrnong, Yarra and South East. 1995 The Victorian Government split Melbourne’s water industry into three retail water businesses (City West Water, Yarra Valley Water and South East Water). Melbourne Water was established as the wholesale water business and Melbourne Parks and Waterways (the predecessor to Parks Victoria) was set up to manage parks. Melbourne Water retains responsibility for the collection, storage and wholesaling of water and for the treatment and disposal of sewage, as well as responsibility for regional drainage and waterways within the Melbourne Water operational boundary. -

Download the 2018 Program

sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/enewsSign up to our free monthly eNews STAY IN TOUCH PROGRAM A E M Welcome to country by Art workshops House tours Leanne Watson and 11am–3pm 11.30am, 12.30pm, Rhiannon Wright, and Join Darug artist Leanne 1.30pm & 2.30pm flag-raising ceremony Watson to create a Register for a 30-minute 10.10am–10.30am message stone. tour of Rouse Hill Smoking ceremony by House from a woman’s Nulungu Dreaming F perspective. 10.30am–10.40am Gumaroy Newman 12pm–1pm N B Hear acclaimed singer and Culture talks Nulungu Dreaming poet Gumaroy Newman. 12.15pm, 1.15pm & 2.15pm corroboree Join a Muru Mittigar 10.40am–11.30am G Cultural Educator at the Celebrate Aboriginal culture Darug language classes Darug display in the through dance and song. in the schoolhouse Rouse Hill Visitor Centre. 11.30am & 1.30pm C O Learn to say hello in Darug NAIDOC BECAUSE OF HER, WE CAN! Boomerang throwing in our 1888 schoolhouse. Weaving workshop with Muru Mittigar 12pm–3pm 10.45am–12.30pm H Learn traditional Sunday 15 July & 1pm–3pm Boomerang painting weaving techniques from Throw a boomerang All day Nulungu Dreaming. and learn more about Drop in and paint your this ancient tool. own boomerang. FOOD & DRINK We acknowledge the First D K Nations Peoples, the Darug I & J & P Get Wild native animal Market stalls display and talks All day Enjoy a BBQ cook-up from peoples, the traditional 11am–2pm Mad Mob, tea and coffee Stalls by Aunty Edna, Watson. Leanne by custodians of the land, and from Darcy St Project and Muru Mittigar nursery, traditional Aboriginal foods pay respect to the Elders, AIME, Gillawarra Arts, at Muru Mittigar cafe. -

August Edition 2016 / 2017 Contents High Tea Collections

International Collection August Edition 2016 / 2017 contents High Tea Collections ................................. 4 Tea Cosies ................................................. 58 Charlotte ................................................... 4 Birdsong ..................................................... 7 Vases ......................................................... 59 Bloom Beautiful ........................................ 10 Butterfly ..................................................... 60 Poppies-AWM ........................................... 14 Black & White Nature .............................. 61 I Love Lavender ........................................ 18 Plume & Perch .......................................... 22 Kitchen Collections .................................. 62 Cottage Garden ...................................... 26 Latigo Bay ................................................. 62 Madame Butterfly Ayako ........................ 28 Harvest ...................................................... 65 Vintage Garden ....................................... 29 Adriatic ...................................................... 69 Blue Hydrangea ....................................... 30 Hennie & Roy ............................................ 71 Ruby Red Shoes Collection .................... 31 Art Studio Collection.................................. 72 Twigseeds Kids Collection ...................... 34 Mug Collections ....................................... 75 My Metallics .............................................. 76