Australian Aboriginal Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Exceptionalism and the Constitutional 'Race Power'

Langton.x_Langton.x 1/02/13 9:31 AM Page 1 Indigenous Exceptionalism and the Constitutional ‘Race Power’ Marcia Langton Constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians is a fraught topic, presenting legal as well as moral challenges, and involves a large set of issues beyond my scope here. I want to explore in this chapter the problem of how to recognise Indigenous Australians in the Constitution, a matter given much thought by the members of the Expert Panel appointed by Prime Minister Gillard in December 2010. Upon the release of the Expert Panel Report in January 2012, some commentators made extraordinary and mistaken claims about its recommendations and findings. One person contended that Aboriginal child bride practices would be legalised, should the government accept these recommendations. Another claim was that it was a racist attack on Australians. None of this is the case, of course, but the hysterical response to the propositions of the Expert Panel, well founded in constitutional law and history, tells us something. Most Australians know very little about our Constitution; few have read it, and even fewer understand it. The main challenge for those who agree with our findings is the poorly understood friction between bring- ing Indigenous Australians firmly into the national polity, and maintaining their exceptionalist status as inexorably different. I hope to suggest a solution to this dilemma; it is not original, 1 SPACE PLACE & CULTURE Langton.x_Langton.x 1/02/13 9:31 AM Page 2 INDIGENOUS EXCEPTIONALISM AND THE CONSTITUTIONAL ‘RACE POWER’ but is a new synthesis of a powerful idea drawn from human rights theory and the Expert Panel’s work. -

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

STUDY GUIDE by Marguerite O’Hara, Jonathan Jones and Amanda Peacock

A personal journey into the world of Aboriginal art A STUDY GUIDE by MArguerite o’hArA, jonAthAn jones And amandA PeAcock http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘Art for me is a way for our people to share stories and allow a wider community to understand our history and us as a people.’ SCREEN EDUCATION – Hetti Perkins Front cover: (top) Detail From GinGer riley munDuwalawala, Ngak Ngak aNd the RuiNed City, 1998, synthetic polyer paint on canvas, 193 x 249.3cm, art Gallery oF new south wales. © GinGer riley munDuwalawala, courtesy alcaston Gallery; (Bottom) Kintore ranGe, 2009, warwicK thornton; (inset) hetti perKins, 2010, susie haGon this paGe: (top) Detail From naata nunGurrayi, uNtitled, 1999, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 2 122 x 151 cm, mollie GowinG acquisition FunD For contemporary aBoriGinal art 2000, art Gallery oF new south wales. © naata nunGurrayi, aBoriGinal artists aGency ltD; (centre) nGutjul, 2009, hiBiscus Films; (Bottom) ivy pareroultja, rrutjumpa (mt sonDer), 2009, hiBiscus Films Introduction GulumBu yunupinGu, yirrKala, 2009, hiBiscus Films DVD anD WEbsitE short films – five for each of the three episodes – have been art + soul is a groundbreaking three-part television series produced. These webisodes, which explore a selection of exploring the range and diversity of Aboriginal and Torres the artists and their work in more detail, will be available on Strait Islander art and culture. Written and presented by the art + soul website <http://www.abc.net.au/arts/art Hetti Perkins, senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait andsoul>. Islander art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and directed by Warwick Thornton, award-winning director of art + soul is an absolutely compelling series. -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

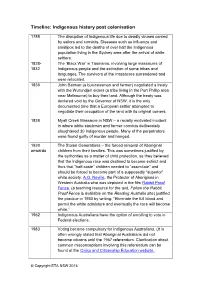

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

A Community-Based Approach to Indigenous Self-Determination

POWER FROM THE PEOPLE: A COMMUNITY-BASED APPROACH TO INDIGENOUS SELF-DETERMINATION LARISSA BEHRENDTt Elliott Johnston impresses me most not because of his involvement with the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody but for his continued conviction about the rightness of social justice despite political climate and personal cost. His membership of the Communist Party no doubt cost him earlier appointment to silk and, as the first Chairperson of the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement, formalised a long commitment to Indigenous social justice and criminal justice issues. He was, is and remains a practitioner and a judge, admired for his acute legal mind and his ability to mix the right legal reasons with the right moral reasons; something that can be found only in the best legal minds. I would like to talk across a few themes tonight. I want to begin by canvassing the current political landscape to identify the challenges to Indigenous rights and their protection. I would then like to talk about the shortcomings of 'practical reconciliation' and the limitations of current government policy on Indigenous issues at the federal level. I would then like to discuss how this direction has marginalised the rights agenda and impoverished debate on the policy options we have. I will argue that the way forward combines short term solutions with long term goals and that this includes an understanding of the relationship between rights, economic development and governance. As part of that discussion, I would then like to canvas a few areas where increased vision would assist in the protection of Indigenous rights. -

The Conversation Rise of Indigenous Art Speaks Volumes About Class in Australia February 24, 2014

FORT GANSEVOORT Rise of Indigenous art speaks volumes about class in Australia February 24, 2014 The children of the wealthy know that mainstream culture belongs to them. urbanartcore.eu The Conversation is running a series, Class in Australia, to identify, illuminate and debate its many manifestations. Here, Joanna Mendelssohn examines the links between Indigenous art and class. The great story of recent Australian art has been the resurgence of Indigenous culture and its recognition as a major art form. But in a country increasingly divided by class and wealth, the rise of Indigenous art has had consequences undreamed of by those who first projected it onto the international exhibiting stage. 5 NINTH AVENUE, NEW YORK, 10014 | [email protected] | (917) 639-3113 FORT GANSEVOORT The 1970s export exhibitions of Arnhem Land bark paintings and reconceptualisations of Western Desert ceremonial paintings had their origins in different regions of the oldest culture. In the following decade, urban Indigenous artists began to make their presence felt. Trevor Nickolls, Lin Onus, Gordon Bennett, Fiona Foley, Bronwyn Bancroft, Tracey Moffatt – all used the visual tools of contemporary western art to make work that was intelligent, confronting, and exhibited around the world. The continuing success of both traditional and western influenced art forms has led to one of the great paradoxes in Australian culture. At a time when art schools have subjugated themselves to the metrics-driven culture of the modern university system, when creative courses are more and more dominated by the children of privilege, some of the most interesting students and graduates are Indigenous. -

Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace Oral Tradition 1/2 (1986): 231-71 Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions Margaret Clunies Ross 1. Aboriginal Oral Traditions A History of Research and Scholarship1 The makers of Australian songs, or of the combined songs and dances, are the poets, or bards, of the tribes, and are held in great esteem. Their names are known in the neighboring tribes, and their songs are carried from tribe to tribe, until the very meaning of the words is lost, as well as the original source of the song. It is hard to say how far and how long such a song may travel in the course of time over the Australian continent. (Howitt 1904:414) In 1988 non-Aboriginal Australians will celebrate two hundred years’ occupation of a country which had previously been home to an Aboriginal population of about 300,000 people. They probably spoke more than two hundred different languages and most individuals were multilingual (Dixon 1980). They had a rich culture, whose traditions were centrally concerned with the celebration of three basic types of religious ritual-rites of fertility, initiation, and death (Maddock 1982:105-57). In many parts of Australia, particularly in the south where white settlement was earliest and densest, Aboriginal traditional life has largely disappeared, although the memory of it has been passed down the generations. Nowadays all Aborigines, even in the most traditional parts of the north, such as Arnhem Land, are affected to a greater or lesser extent by the Australian version of Western culture, and must preserve their own traditions by a combination of holding strategies. -

Emerging Environmental Issues for Indigenous Peoples in Northern Australia - Marcia Langton

QUALITY OF HUMAN RESOURCES: GENDER AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES – Emerging Environmental Issues For Indigenous Peoples In Northern Australia - Marcia Langton EMERGING ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES FOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Marcia Langton School of Anthropology, University of Melbourne, Australia Keywords: indigenous peoples and environmental issues, Aboriginal impact, people in landscapes Contents 1. Introduction 2. Science Fictions 2.1. Wilderness 2.2. The Nature of Aboriginal Land 2.3. Changes in the Nature of Aboriginal Land Use 3. Pre-settlement Aboriginal Environmental Impact 3.1. Fire and Human Shaping of the Landscape 3.2. Fire: the Recent Debates 4. Re-implicating Aboriginal People in Landscapes 4.1. Dhimurru Aboriginal Land Management Corporation 4.2. Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation 4.3. Arafura Wetlands 5. Conclusion Bibliography Biographical Sketch 1. Introduction The quest for environmental justice for Australian indigenous people requires, among other things, a critical examination of historical assumptions, which shape arguments concerning the role of Aboriginal people and their traditional environmental knowledge in the management of their cultural and physical landscapes. This paper surveys some recent literature and indigenous conservation developments that provide evidence of the re-implication of Aboriginal people in the management of tropical northern Australia. For 205UNESCO years the legal fiction of terra – nullius EOLSS rendered native title, Aboriginal Land Law And Aboriginal Persons As Land Owners Under That -

Raising Awareness of Australian Aboriginal Peoples Reality: Embedding Aboriginal Knowledge in Social Work Education Through the Use of Field Experiences

The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 2013, 12(1), 197–212 iSSN 1443-1475 © 2013 www.iejcomparative.org Raising awareness of Australian Aboriginal peoples reality: Embedding Aboriginal knowledge in social work education through the use of field experiences Deb Duthie Queensland University of Technology, Australia Julie King Queensland University of Technology, Australia Jenni Mays Queensland University of Technology, Australia Effective social work practice with Aboriginal peoples and communities requires knowledge of operational communication skills and practice methods. In addition, there is also a need for practitioners to be aware of the history surrounding white engagement with Aboriginal communities and their cultures. Indeed, the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) acknowledges the importance of social workers practising cultural safety. Engendering knowledge of cultural safety for social work students is the opportunity to listen and talk with Aboriginal people who have experienced the destructive impacts of colonisation and the subsequent disruption to family and community. This article discusses the use of field experiences within a Masters of Social Work (Qualifying) Program (MSW) as an educational method aimed at increasing student awareness of contemporary Aboriginal issues and how to practice effectively and within a culturally safe manner. KeyWords: Aboriginal Australia, social work education, cultural safety, field experiences, blended learning. Australia was colonised by Great Britain in the late 18th Century. From the outset, the impact on Aboriginal peoples was detrimental on many levels. As has been well documented, this impact has taken many forms, from semi-official extermination (Lake & Reynolds, 2008; Richards, 2008) through to social engineering policies of less 197 Raising awareness of Australian Aboriginal peoples reality obvious brutality. -

2.5: a Journey Towards Adolescence and an Aboriginal Dance Method

2.5: A Journey towards Adolescence and an Aboriginal Dance Method Michael Leslie A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts University of New South Wales Art and Design December 2016 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Leslie First name: Michael Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Master of Fine Arts School: Paddington Campus Faculty: Art & Design Title: 2.5: A Journey towards Adolescence and an Aboriginal Dance Method Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This project records my history as an Aboriginal dancer who trainedboth in Australia and the USA. The end result of this history is a new Aboriginal Dance Method, which seeks a synthesis with African American dance, and other contemporary dance fonns. In describing This new fonn, is informed by Gamilaraay Language, culture, mammals, birds, reptiles, qualities, elements, moving, parts ofthe body, material culture, water, doing, places, times,and questions. The dance sequence will include contemporary techno music and theatreto synthesise and to explore this new dance typology via the use of 100 steps drawn fromthe Gamilaraay language. These 100 steps are the core creation ofthis Masters. Is it possible to synthesise into another essentially "Aboriginal Dance Method" modern European ballet, physical theatre,African American dance and both ancient and modernAboriginal dance types? The urban Aborigine is oftendivorced, like myself, fromtraditional initiation ceremony and hence cultural Rights of Passage. Loss ofritual and ceremony coupled with racism and no safeplace to exist in society, has generated a mark milestone of institutionalism or goal time as a mark of being a man. -

Atomic Testing in Australian Art Jd Mittmann

ATO MIC TEST ING IN AUST RAL IAN ART JD MIT TMA NN Around the world artists have be en conce rned wit h Within a radius of 800m the dest ruction is co mplete . and Walle r. He docume nted the Austr alian New Gui nea nuclear iss ues, from the first application of atomic bomb s Over 70,000 die instantl y. campaign and its afte rmath . at Hi roshima and Nagasaki, to at omic testing, uraniu m A person stan ds lost amongst the ruins of a house . In 1946 he was se nt to Japan whe re he witnes sed mining, nuc lear waste tra nspo rt and storage, and We don’t see the chi ld’s exp ression, but it can only be the effects of the ato mic bomb. He doc umented the va st scenarios of nuclear Armageddon. The Australian artisti c one of shock and suffering. A charred tree towers ov er dest ruction from a distant vi ewpoint, spa ring the viewe r response to Bri tish atomic te sting in the 195 0s is les s the rubble. Natu re has withe red in the on slaught of hea t the ho rri fic deta ils. His sketch Rebuilding Hiroshim a well-know n, as is the sto ry of the tests . and shock waves. Simply titled Hi roshima , Albe rt Tucker’ s shows civil ians clearing away the rubble. Li fe ha s Cloaked in se crec y, the British atomic testing progra m small wate rcolour is quiet and conte mplative.